The Liberace of Stephen Soderbergh’s Behind the Candelabra (which premiered last Sunday on HBO) seems quite comfortable in his own skin. And yet, everywhere in Liberace’s life are signs that he apparently wanted to be just about anything other than what he was. There were, first of all, those costumes, lifted from a fantasia of how anyone dressed at any point in, you know, human history. He didn’t use the name he’d been given—everyone called him Lee, instead of his real name, Wladziu. He claimed to love women when, in fact, well, no. He tried to be a movie actor, a television actor, a sort of walking tourist attraction. Apparently, “just” being a millionaire classical pianist—an improbable path to success if ever there was one—brought him insufficient rewards (other than money, that is). To his critics, he was a big user of that phrase, “I cried all the way to the bank.”

Yet it’s certainly true that the façade was all about maintaining a sort of unqualified experience of joy. The shows were deliberately exuberant. The film gets this across pretty well in its first few minutes, sending Scott Thorson, played by a young-looking Matt Damon (at 42 he’s playing 17) to a nightclub to watch in rapture. Michael Douglas, bringing his voice an octave higher, is clearly enjoying the hell out of his performance, though to what degree that channels Liberace’s own actual act it’s hard to say, let alone the man’s life overall. Time and gay liberation have revealed things that were once obscure.

For example, Soderbergh’s version doesn’t suggest much visible stress on Liberace’s part over the difficulties of concealing his gayness. That not only defies reason, it defies the facts; the chill of the lawsuits Liberace habitually threatened the press with suggests a deep current of anxiety. Not to mention that there’s a sort of predatory creepiness to a man who consistently seeks out very young men, plies them with liquor and jewelry, and then dumps them when they get too old. But then, Behind the Candelabra, like Magic Mike, another recent Soderbergh film, is almost wholly devoid of anxiety. It is about the joy of doing something perhaps hugely tacky and even devoid of artistic merit but which nonetheless has something in it.

There’s a lightness of touch to it that feels almost John Waters-esque, with Soderbergh pandering to mainstream tastes much more easily than Waters ever has. Though perhaps that actually makes Soderbergh the better master of camp.That, of course, is a matter of debate over which interpretation of camp you subscribe to: Susan Sontag’s, or the later queer version, more associated with Judith Butler.

In the essay that made her famous, “Notes on Camp,” Sontag wrote that “camp is generous. It wants to enjoy… What it does is to find the success in certain passionate failures.” There is a slippage between popular taste—which frequently “enjoys” such drivel as Transformers or Avatar—and the camp taste we’re talking about here, though. Someone like Sontag might argue that a James Cameron film is too cynically calculated to make money to qualify for the “passionate” half of the equation. And yet, she would be saying this of a man who gave an awards acceptance speech in the made-up language of his people, which translated roughly as, “I see you, my brothers and sisters.” His manner was not, you might say, without passion.

But then that just reveals there is a tension in the whole idea of camp these days. Think, for example, of RuPaul’s Drag Race. Drag has always been something of a paradigmatic example of camp. And yet: Is it a passionate failure? Is it one in the way RuPaul presents it, anyway? Drag Race wants to enjoy, too, but it also survives on bitchery, like most reality television. The moments of fabulousness are leavened with a lot of sour insults, and fights, calculated to bring the ratings up and deliver a steady diet of excitement to the audience. And where it is sweet, the moments are supposed to be unmitigated triumphs of self-determination. The queer theorists who criticized Sontag’s declaration that “camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical” are better at assessing modern drag. It turns out that it isn’t experienced as failure at all.

Soderbergh’s cheerful Liberace, therefore, suddenly seems justified. But there’s a politics to the way all hints of the sordid side of this tale reside in other characters. Thorson has a drug addiction; the plastic surgeon played by Rob Lowe looks disfigured by the adventures he’s had with his own face; Liberace’s manager acts like something of a mob boss. But the star in the center is all light. The most questionable thing he does in the whole movie is get a facelift that leaves him unable to close his eyes at night. And in that context, it’s difficult to get much of an emotional hold on the injustices visited on Thorson (arguably the protagonist of the piece).

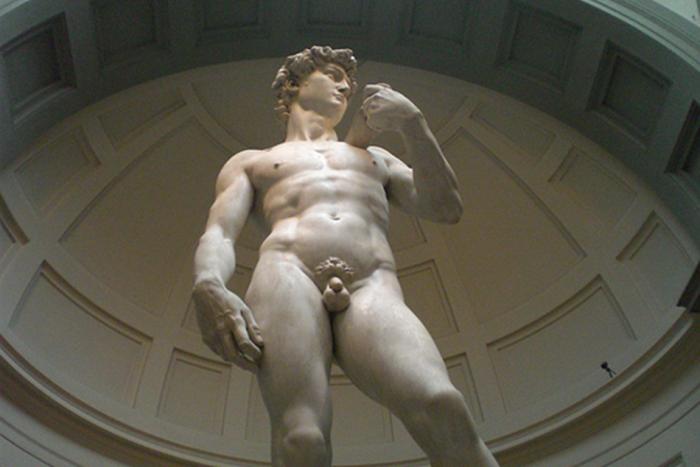

No one is saying, of course, that Soderbergh should have made a movie that scolded Liberace for being less than forthcoming about his personal life. The politics of the closet have changed, and to demand it of anyone based on the contemporary reception of gay celebrities is at best anachronistic, and at worst terribly naïve. But it’s a strange thing to be so sanguine about the costs of it, to let them come across as largely neutered by all the Ionic marble columns in the bathroom. Of course the point of camp is that it kind of evades an aesthetic judgment, or at least a very definitive one. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t an emotional experience that ought to be reflected in it.