“I’m suffering from a headache and the universe.” — Fernando Pessoa, writing as Bernardo Soares, The Book of Disquiet.

Karl Ove Knausgaard opens the third volume of My Struggle, his memoir (or fictional autobiography, or subjective-novel or whatever it is), with a vivid scene. A young Norwegian couple travels by bus with their two children. One child is four and a half years old, the other an infant in a stroller. The bus “belonged to the Arendal Steamship Company and was, like all its buses, painted in two-tone light and dark brown livery. It drove over a bridge, along a bay, signaled right, and drew to a halt.” It’s 1969. The couple is Karl Ove’s parents. The infant is Karl Ove.

Reading Knausgaard is like running your hand along finished wood: seamless, fluent, and only a hardcore quibbler would feel the splinter here: is this a memory? Can’t be. The author in this scene is in a stroller and capable, at best, of forming saliva bubbles and wetting himself, but not of soaking in the novelistic detail, so it’s either a writer’s gimmick or he’s up to something else, and with Knausgaard it’s safe to bet on the something else. “Memory,” he says, only a few pages later, “is not a reliable quantity in life… It is never the demand for truth that determines whether a memory recalls an action or not. It is self-interest that does.” Which is an elegant and Scandinavian way of saying that memories are lies: they make up the screenplay (adapted from original material) for the movie in our heads.

Memories complicate Knausgaard’s project in interesting ways. He is writing his life story. It is told in great detail. It reads as an honest account, meaning he’s not embellishing to make himself look better (far from it), and yet he admits that his own raw materials are suspect. That leaves us with a dilemma: who is My Struggle about? A real person, or some kind of ghost that Karl Ove Knausgaard has conjured out of words? “From all these bits and pieces I have built myself a Karl Ove,” he writes, by way of an answer. The image is of Mary Shelley’s monster. But the Karl Ove that Karl Ove builds is more like the narrator in Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, a fictional diary written in the early decades of the last century, stored in a trunk, and published after the author’s death.

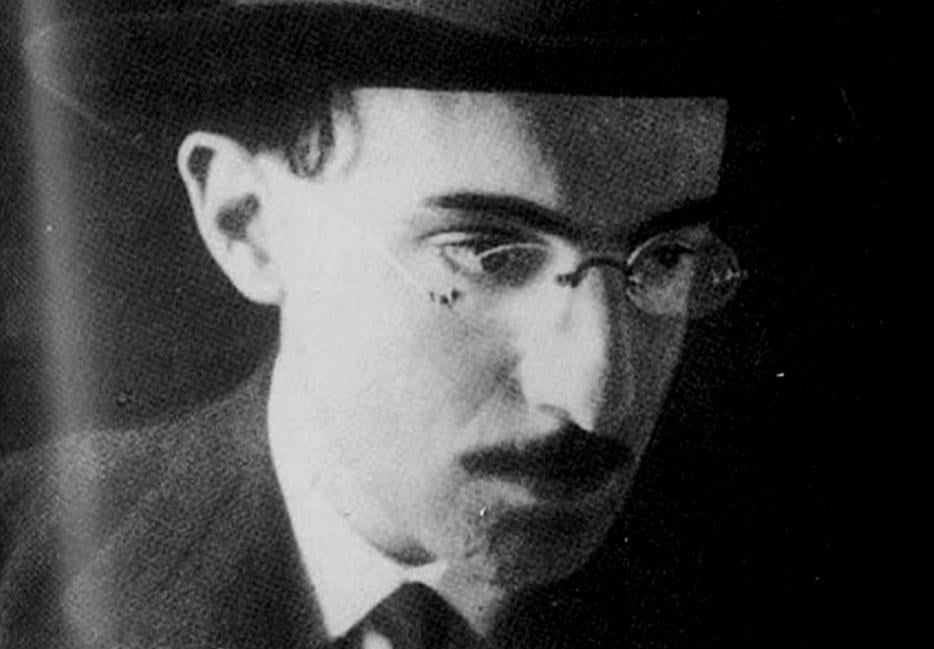

Pessoa was born in Lisbon in 1888 but grew up in South Africa. He returned to Portugal for university and made a modest living writing commercial copy and poetry. The poetry he published under fake names, which he called “heteronyms.” These were not just pen names, but full-blown surrogate Pessoa-likes with their own biographies, writing styles, and personalities: Alvaro de Campo, Ricardo Reis, Bernardo Soares (who “always appears when I’m sleepy or drowsy, so that my qualities of inhibition and rational thought are suspended”), and more than 70 others, created by the lonely author to carry his work to his readers, who were few.

Reading Knausgaard is like running your hand along finished wood: seamless, fluent, and only a hardcore quibbler would feel the splinter here: is this a memory? Can’t be.

His masterwork was The Book of Disquiet: a plotless collection of impressions and observations credited to Bernardo Soares, a bored Lisbon bookkeeper. Pessoa builds him in bits and pieces. He called the book a “factless autobiography.” The translator of the Penguin Classics edition encourages the reader to open the book at random and work from there. “Everything around me is evaporating,” writes Pessoa-as-Soares. “My whole life, my memories, my imagination and its contents, my personality — it’s all evaporating. I continuously feel that I was someone else, that I felt something else, that I thought something else. What I’m attending here is a show with another set. And the show I’m attending is myself.” Which is an elegant and Portuguese way of saying that our past selves are fictions. Pessoa and Knausgaard have this in common: a keen awareness of their own slippery identities, based as they are on fragile memories.

When I was a kid living in Brockville, Ontario, I used to explore the banks of the St. Lawrence River not far from the psychiatric hospital. They weren’t so much banks, though, as rocky cliffs that led to a drop of many many metres. One day I found a scrap of fabric stuck in a tree branch near the cliff. It was light blue. I decided that it had been torn from a piece of clothing belonging to some mental patient who’d thrown herself off the cliff to her death. A couple of years ago I went back to Brockville, with my wife, and found the spot where I used to play. I had a hunch the drop wasn’t as steep as I remembered it. And looking at the trees I could no longer place that scrap of fabric in my mind, and I wondered if I’d made that up too. And yet, the memory is vivid. I can see the scrap as I write this.

This is banal stuff, hardly traumatic, but there’s purpose in telling it: the details are irrelvant (who cares what I may or may not have found in a tree) but the struggle to remember it is what matters. If it didn’t happen as I remember it, then who is that Brockville boy in my head? This is a struggle we share, with Pessoa and Knausgaard, who tell stories not to report on the details of their lives but to trigger an emotional response in the reader: we’re all forgetting our past selves.

Pessoa (as Soares) puts it this way: if I’m sad about life, I can’t communicate this to a reader except in a vague, uninteresting way, by saying I’m sad about life. If, however, I write about my lost childhood, “going into poignant detail about the people and furniture of our old house in the country,” the reader will relate, because he too has lost his own childhood. He feels sad. “[S]o we make use of lies and fiction to promote understanding among ourselves,” he writes, “something that the truth — personal and incommunicable — could never accomplish… We all love each other, and the lie is the kiss we exchange.”

This is what Pessoa and Knausgaard are up to when they interrogate memory, and tell vivid stories about what may or may not have happened, through characters they’ve invented, deliberately or otherwise. The documentary facts are irrelevant. What they communicate through some narrative voodoo, between writer and reader, is what matters: both of these men are grieving for a past that turned into a different present than they’d hoped. They are “suffering from a headache and the universe,” and in writing, they are banking on the spark of recognition: this happened to me and you, too.

The too-long-didn’t-read version of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, now at six volumes and over 3500 pages (the last three volumes haven’t yet been translated into English), covering a period from birth, to a trip aboard the two-tone Arendal Steamship bus, to drunken teen parties, to the death of his father, to the present, is this: Karl Ove is sad. Three-thousand five-hundred pages to say four words. But then the point of art is to take a long time to say something very simple.