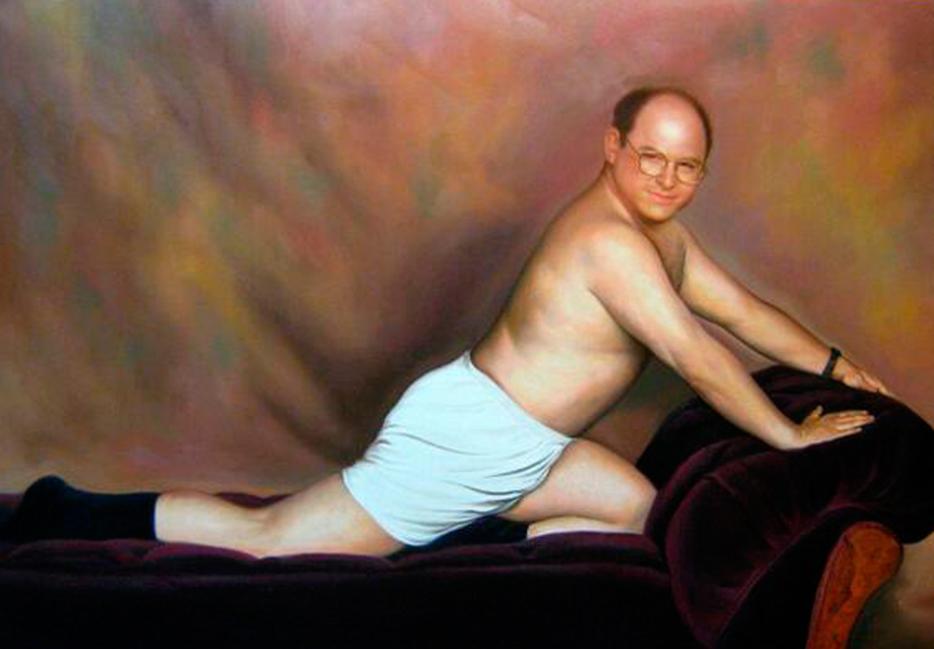

If you had to pick a symbolic figurehead for the digital future, you have some good choices: Mark Zuckerberg, of course; Elon Musk, perhaps; hell, maybe Tavi Gevinson. But, in light of some recent trends, I’d suggest that when it comes to the digital future, we line up behind another great thinker: George Costanza. Because, for all the buzzword-filled talk of “social,” “disintermediation,” or “curation,” only our dear, bumbling Costanza is familiar enough with the idea that is truly shaping the digital world: shrinkage.

To shrink and condense information is the new tenor of the digital age. From its inception, the Internet as both technology and concept has been inextricably tied to “more,” but that overwhelming throbbing mass of information now requires an inversion. Put it however you want—less is more, small is the new big, the trickling stream rather than rushing torrent—but shrinking the tsunami of information into manageable chunks is clearly the new way forward.

Just look at the white flag Facebook raised in a recent blog post. Though ostensibly about “organic reach”—the number of people brands can reach on Facebook without having to pay—what was really going on was twofold: first, that Facebook realizes it has brands by the throat; but second, that there’s just too much stuff in people’s feeds to toss it all out there in a so-called “organic” manner, simply listing all the things posted by those you’ve friended or liked. The only option is the algorithm, an automated way to shrink and filter. Facebook’s success is now its curse: the world it has created has become too noisy for it to function effectively, or for us to find its value.

The move by the big blue social network isn’t isolated, though. There are other, smaller, if perhaps more symbolic things happening. On Twitter, @attentivebot is an automated account that tweets things you may have missed from those who only post infrequently. It’s useful, but also a symptom made manifest in the form of a bot: even in a list you yourself craft, there’s just too much to keep track of.

Experimental accounts like this, however, are accompanied by much bigger plays. Shrinking is everywhere. Companies such as Percolate aggregate what’s going on in your Twitter feeds and send it to you in an email—a tactic now appropriated by Twitter itself, which has started sending missives about what’s happening in your timeline. Twitter has also instituted a mute function to help cut down on noise in your feed. In the media world, the Ottawa Citizen has launched an iPad app that culls the best of the newspaper every day and puts it out at 6 p.m., rather than having a constantly updating app. And Digg and a slew of clones continue to filter through headlines and articles to tell you what people are reading, shrinking it all down to help make the morass of stuff more manageable.

Perhaps most significant, though, is the move The New York Times has made in the form of NYT Now, an app that does something decidedly old-school: NYT editors curate and edit the stories they deem to be most important, and then put those—and only those—in the app. It’s all the news that’s fit to skim. Or, as Craig Mod elegantly put it, NYT Now provides an edge to an otherwise infinite sea of information—that he found using the app “bounded the boundless.” The remarkable change about something like NYT Now? On a given morning, you can actually—imagine this—finish it. Shrinking is a psychological reaction to infinity.

There are real ideological struggles contained here. After all, if there’s a kind of existential relief in the “shrinking” enabled by NYT Now telling you what to read, what then becomes of the dream that the web might democratize information—that we have left behind the dictatorial whims of an elite telling us plebes what to read?

There is no point in dredging up, yet again, the amateurs vs. professionals debate, particularly because the web has rendered the difference (mostly) inscrutable. Yet, what becomes impossible to ignore is that the demand for less is a response to the social technology of the web itself. In producing a medium with the potential for a limitless “more,” that is what we ended up with, because that is the nature of technology: it will always appeal to the best and worst in us. We are left with, now, is the tyranny of democracy, the trouble being the same as it was with the newspaper and the TV before it. It is the id—and, further, the continually increasing pace with which the id can be satisfied. That term, which we give to our surging desire to want and to be gratified, has found its ultimate expression in the web, and now we find we must invent technologies to help us say “stop!”

If media is now seeing a way forward in cutting down, though, people are responding in kind. The incredible rise of messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Line, and Google Hangouts means a shrinking of social circles—a reduction of one’s Facebook friends list into four or five people in a WhatsApp chat. Instead of broadcasting to an amorphous group, it’s a digital version of a chat around the living room table—intimate, small, the digital social once again “shrunk.”

There are complex dynamics here. Scale is not the only thing that changes, but “publicity,” too. What characterizes social media is that it is about making things public, even if that public is the 150 friends you have on Facebook. Yet even there, it is the threat of an unknowable “more” that underpins the trouble with social media—that any post or tweet might engulf half of your day as, entirely to your surprise, a hundred people respond when you were only expecting three. If Facebook recognizes that there is too much to read, we are realizing that when social media gets too big, there is too much to “write” as well.

So, shrinkage: cold water splashed on the altogether too grandiose, tumescent dreams of digital media companies so that life might remain manageable, comprehensible—that it is given some kind of edge. And it isn’t that Facebook, and Twitter, and the rushing stream of news doesn’t still have its place, a kind of surging torrent one can dip into in necessary moments. What we are in the midst of now is the creation of a healthy middle ground: a social media that is not always public to the world by default, but often limited to small groups; a news stream that is not forever an endless fount of novelty, but a circumscribed mixture of the social and the editorial; and a media experience that, in its newly humane and shrunken form, no longer needs a “digital” qualifier in front of it, because it won’t be so radically, overwhelmingly, crushingly “more.” Let this painting be your reminder that, in the face of a limitless digital sea of information, shrinkage is the way forward.