On September 7th, 1907, a parade of several thousand people carrying banners for a “White Canada” marched on Vancouver’s City Hall. They rampaged through Chinatown and nearby Powell Street, the heart of the Japanese community, smashing windows and terrorizing families. Lillian Ho Wong, who was 12 years old at the time, told historian Paul Yee, “Papa came back and said, ‘Don’t put on the lights! And don’t sit near the windows!’ They were running through all the lanes, making all kinds of noise. We had no lights on, so they couldn’t see us. We sat in the centre, so that if anything happened at either end, we could still run out.”

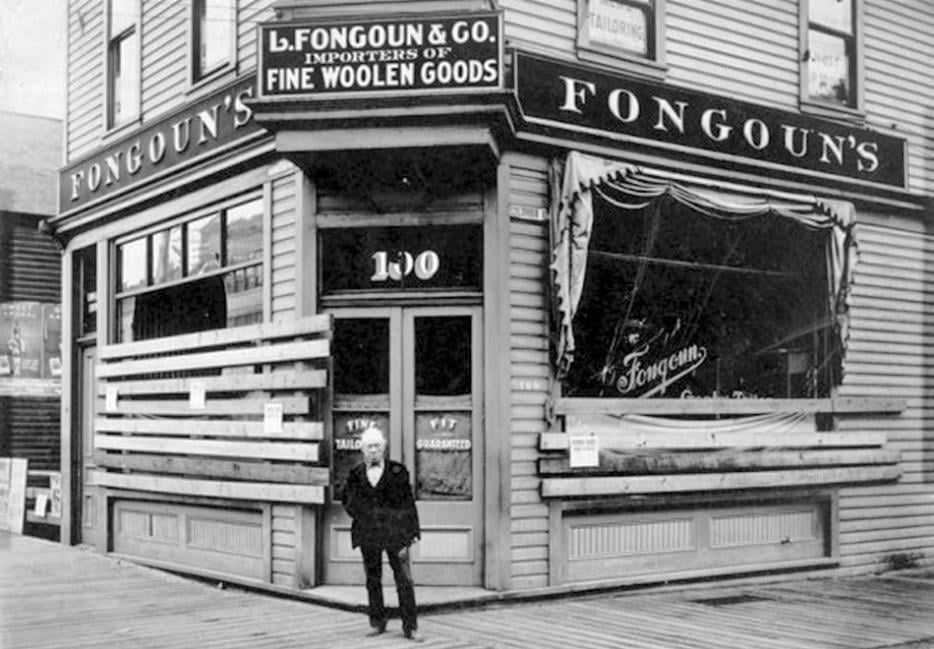

In 1907, “Chinese immigrant” was synonymous with “poor and powerless,” and the Chinese foothold in Vancouver was in the least desirable area. Chinatown, as Julie F. Gilmour writes in her new book, Trouble on Main Street: Mackenzie King, Reason, Race, and the 1907 Vancouver Riots, was “a neighbourhood of unregulated rooming houses and shacks that was a poorly serviced, often squalid part of the city.” There had been a Chinese presence on the West Coast since the 1850s, when a gold rush in the Fraser Canyon attracted migrant workers both from California and from mainland China. In the 1880s, Chinese labour was crucial to the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and many former railroad workers settled in Vancouver. By 1885, popular sentiment against Chinese workers resulted in the government instituting the infamous Head Tax as a deterrent to Chinese immigrants. In 1923 the Chinese Immigration Act—unofficially known as the Chinese Exclusion Act—outright banned Chinese immigration into the Dominion of Canada. It wouldn’t be repealed until 1947.

China’s position in the world has changed. And the stereotype of the Chinese presence in Vancouver has changed too—if the old image was of a blue-collar worker living in close quarters and sending money home to China, the new image is of a cosmopolitan billionaire buying up luxury property as a way to park money outside of China. “Is Vancouver Ready for 52,000 More Wealthy New Immigrants?” a Vancouver Sun article asked in February of this year, in an article about how Canada’s (now cancelled) immigration program for millionaire investors has resulted in an influx of rich Chinese mainlanders to Vancouver. A blog called Canadian Immigration Reform asks, more pointedly, “Vancouver: Canadian City or Chinese Colony?”

China’s position in the world has changed. And the stereotype of the Chinese presence in Vancouver has changed too—if the old image was of a blue-collar worker living in close quarters and sending money home to China, the new image is of a cosmopolitan billionaire buying up luxury property as a way to park money outside of China.

In marvelling at Vancouver’s housing prices—the highest in North America, ahead of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles—James Surowiecki recently wrote in The New Yorker, “Vancouver, which has a large Chinese population, easy access to the Pacific Rim, and nice weather, has become a magnet for Chinese investors looking for insurance against uncertainty.” The housing market in Vancouver, he writes, may be more closely tied to China’s economy than to the actual incomes of Vancouverites.

But whether Vancouver’s high prices are a result of Chinese investment is the subject of extensive debate in the city—in part because there is limited conclusive data on foreign ownership of real estate. Andy Yan, a senior urban planner with the city’s Bing Thom Architect firm, gave a presentation at a housing conference last year in which one of his slides asked, “Is the Issue Foreign Investment in Vancouver Real Estate? Or Investment in Vancouver Real Estate?”

As Nathan Crompton wrote in The Mainlander, “One of Yan’s most significant findings is that a majority of property assessments for Vancouver condos are sent to investors living in the Lower Mainland. Almost all landlords and property investors are local residents, a majority of them holding primary residence in West-side neighborhoods like Point Grey and Shaughnessy.” The prevalent urban myth that Chinese investors are buying up condos in downtown Vancouver and then leaving them empty—resulting in “zombie neighbourhoods”—isn’t borne out by existing research. The foreign ownership that Yan has been able to track suggests that Americans are the main foreign buyers of Vancouver real estate, followed by China and then Japan, Hong Kong, and the UK.

One of the statistics Surowiecki cites is from a report by Sotheby’s International Realty, which states that of 1200 luxury homes sold in the first half of 2013, nearly half were bought by foreigners. For $18.8 million, Sotheby’s currently lists a house—or perhaps “architectural marvel” is the only phrase—on the Dundarave waterfront, with six bathrooms, four bedrooms, and an expansive outdoor patio. Owners can walk on the beach and then watch the sunset while swimming laps in their oceanside pool. “For the car enthusiast,” Sotheby’s writes, “there is a 10 car garage with automobile elevator.” Gourmet kitchen, guest suite, nanny quarters. Would white Canadians who can’t afford beachfront property rather see these homes owned by pasty Americans or Brits rather than by Chinese businessmen? Who do we believe deserves to live here?

While “White Canada” is no longer an overt value in our government and institutions, the turn-of-the-century bias against Chinese communities hasn’t simply gone away. In 2013, The Georgia Straight ran an article on what some consider a rising tide of Sinophobic sentiment in Vancouver. Architect David Wong wondered why there was so much rhetoric about a proposal to hire 200 workers from China for a northern B.C. coal mine, when a similar plan to increase the number of young Irish workers seemed to be uncontroversial. The article quoted labour studies professor David Camfield saying, “All this racist history has left its mark on Canadian society, and it affects how people interpret these issues today.”

Would white Canadians who can’t afford beachfront property rather see these homes owned by pasty Americans or Brits rather than by Chinese businessmen? Who do we believe deserves to live here?

In 1907, white Canadians—most of them, presumably, immigrants or children of immigrants themselves—found the idea of a visible Chinese presence in Vancouver unpalatable. The current narratives about Chinese presence in the Vancouver area seem almost metaphysical—downtown, Chinese investors are blamed for owning property they don’t live in and so failing to contribute to the life of the neighbourhood (being unseen), but in nearby Richmond Chinese people are blamed for changing the character of neighbourhoods (being seen).

About 45 per cent of Richmond’s population is Chinese, and its signage reflects the strong presence of Chinese speakers. Last year, the Richmond city council received a delegation asking that Chinese language on public signs, shopfronts, advertising, and mailouts be limited. Resident Kerry Starchuk, who co-organized the delegation, told the Richmond News, “We’re not saying there shouldn’t be Chinese language on signs...But this isn’t right and it’s all the way through Richmond, not just the city centre and the lack of English is way out of proportion.” She won’t drive up the No. 3 Road anymore because of the predominance of Chinese signage. If no steps are taken, she said, English might disappear altogether.

In the introduction to Gilmour’s Race Riots, historians Margaret MacMillan and Robert Bothwell call Canada “a success story.” Part of what they mean by that success is that “White Canada” just isn’t what happened. According to StatsCan, in 2011 visible minorities made up 45.2 percent of Vancouver’s population. In Toronto, it was 49.1 percent, and 20.3 percent in Montreal. One in five Canadians was a member of a visible minority group.

Vancouver consistently classes as one of the top places to live in the world, and part of what makes the city attractive is its diversity. Where in the early 20th century, “racial purity” was the mark of a successful city, in the 21st century, diversity is almost synonymous with the urban experience—a city with little variation in its ethnic makeup seems like a backwater. If the 1907 rioters had succeeded in growing their city as a monocultural enclave, Vancouver would have none of its current world-class status. Real-estate there wouldn’t be worth fighting over.