In 1989, the Guerilla Girls asked: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” On the cusp of 2014, the question still stands—what will it take to move women from subject to creator? During the last few months of 2013 alone, New York City’s prestige museums focused their big exhibitions almost exclusively on male artists. There was Magritte at the MoMA, Chris Burden at the New Museum, Robert Indiana at the Whitney, and Balthus at the Metropolitan, to name just a few. “This is an art season that could make you think that the feminist movement never happened,” commented WNYC art critic Deborah Solomon.

The term ‘art’ has always been freighted with the most exclusionary restrictions, regardless of season. But there have always been women artists operating outside the canon—from Artemisia Gentileschi to Kara Walker—whose work interrogates the meaning and making of art in a social context. Or, as Linda Nochlin says in her essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”:

“…women can reveal institutional and intellectual weaknesses in general, and, at the same time that they destroy false consciousness, take part in the creation of institutions in which clear thought and true greatness are challenges open to anyone—man or woman—courageous enough to take the necessary risk, the leap into the unknown.”

It’s a thread that will be picked up on this Thursday, when four Canadian artists meet at the Art Gallery of Ontario to discuss the many ways that feminism influences their work. Featuring Shary Boyle, Petra Collins, Vanessa Dunn, Aminah Sheikh, and moderator Nicola Spunt, the group will explore “21st Century Art: Why Feminist Art Still (Really) Matters” as part of the AGO’s First Thursdays program and the Long Winter Takeover.

“The idea of intersecting art with feminism came pretty instantly,” says Spunt, the founder of After School, a salon-style speaker’s series in Toronto. “Feminism remains this dirty, misunderstood word. After School’s mandate is to reimagine possibilities for higher learning—to open up access to all kinds of amazing and engaging thinkers, writers, artists. Feminism, for me, is about deconstructing our blind spots to privilege, power, and oppression, and is something that we still need to be talking and learning about.”

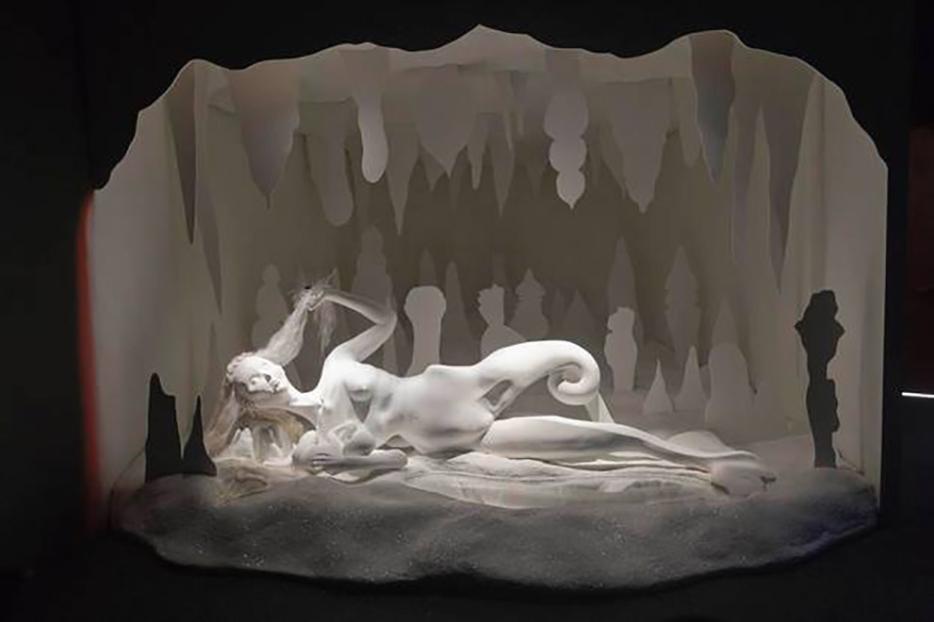

Spunt deliberately chose four women who represent a cross-section of artistic mediums, generations, and backgrounds. Shary Boyle works primarily in visual arts, fusing sculpture, performance, and painting; this year, she represented Canada at the Venice Biennale, a game-changing accolade. Petra Collins is a photographer who works with publications such as Rookie, Purple, and Oyster, as well as founding The Arduous, a photography site featuring the work of young women. Vanessa Dunn is a singer in VAG HALEN, a feminist queer art rock band, as well as a writer and actress. Aminah Sheikh is a graduate of York University whose research focused on faith-based organizations, women, and socio-economic development in the Middle East and South Asia; Sheikh also contributes to artistic projects related to the faith, identities, and politics of Muslim women.

On a cold Wednesday night, I met with Boyle, Dunn, and Sheikh at Spunt’s house in Toronto’s Brockton Village where they were preparing for the panel (Collins was travelling and unfortunately unable to attend).

The goal of this panel is hardly to solve the problem of feminism and art once for all. Rather, as Dunn says, “I hope people come and ask questions so it can be more of a larger conversation. I want to know what their versions of feminism are. I have as much to learn as I have to say.”

Sheikh agrees, saying, “Women are not a homogeneous group that can be lumped together, but many share the same goals and strategic needs. It’s possible to have a global feminist movement. They just need to be looked at through lenses other than the dominant war-orientalist-neo colonialist narrative pushed by patriarchal-capitalist politics.”

“Politicized women have been wary for a long time of being ghettoized in the arts by their gender,” says Boyle. “My art is made by Shary Boyle, a very specific individual with a huge set of experiences that have formed my sensibilities. It’s impossible to ‘represent’ any group. I identify publicly as a feminist in order to advocate against gender oppression and inequality. To activate the conversation, which is very much alive if underground.”

No one here wants to enforce a strict definition of what makes a feminist artist.

Sheikh: “I don’t think, necessarily, the artist has to say their intention is to take on all these feminist models. I look at Iranian artists, women artists, who come from the right and are very religious and contributing to [art] in a very different way, talking about feminism in a different way. The artists I look at, like Shirin Neshat, I like because she shows the weight on Muslim women to be the image of their community.”

“As soon as a woman steps up on stage, I consider her a feminist,” says Dunn, because “there is a sense that they don’t belong up there. I would say that [women] are programmed to second-guess ourselves constantly, to look over our shoulder. I don’t want that. Feminism has a history and you’re fighting the historical context with that word.”

“I’ve always identified as a feminist, but fuck it, I’m sick of getting undermined, belittled,” says Boyle. “It becomes this question of, do you have to replicate that academic art world thing in order to be respected? Like that corporate thing, if female CEOs act like men, they can be accepted. Do I have to be a male artist? People feel like women are a special interest group. We’re fucking half of the world, why are we special interest?”

If the art season of fall 2013 seemed to suggest that feminism never happened, the conversation on January 2 at the AGO should serve as a reminder that there’s a very real and diverse community of women artists working outside of institutionalized walls—one that’s redefining in some measure how we make art and what it means to be an engaged artist.

“We’re not a part of the conversation historically,” says Boyle. “We have to validate why we belong. I absolutely want to feel like I can take for granted my equality. But I also feel like, for me, feminism denotes a stance of anti-oppression, anti-racism, anti-violence, the ways that power is kept and maintained. How many social orders have to be overturned to get that? You can’t represent anybody but yourself, the question is too big, so you try to do it on the small level. Feminism is for everybody.”

--

21st Century Art: Why Feminism Still (Really) Matters, as part of the Long Winter Takeover at AGO First Thursdays, presented by After School and Hazlitt. Thursday, January 2, 7 pm, Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas St. West, Toronto.

Tickets for Long Winter Takeover $12 in advance, $15 at the door.