It was raining when I got up, raining as I climbed into the media shuttle bus, and still raining when, just shy of 6 a.m., we pulled into the parking lot of the massive earth-hued calabash that is the Soccer City stadium, located just outside the sprawl of Soweto. As the first busload of journalists disembarked and hurried to stake out a good place for the long wait before the State Memorial Service for Nelson Mandela got underway, one of the questions on everyone’s mind—other than, “Can they really pull this off?! Security for Obama and the rest of the leaders?”—was how exactly would the state pay tribute to a man so globally iconic yet held so dear by the South African people?

As we walked across a half-empty parking lot and through the unguarded media entrance, then kept on walking as the unmanned metal detector at the security checkpoint blared, we had our answer to the first question (nope). The answer to the second was less immediate.

*

No matter what side of the colour line you were born on, Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 and his election as the nation’s first democratically elected president in 1994 changed life here tangibly and irreversibly. Madiba’s biography is as complicated as his cultural context. He was a (royal) village boy who matured to greatness. He was a political prisoner. A declared terrorist. A freedom fighter. He was a lawyer. An activist. A president. He was a son. A husband. A father—to his own children and to the Rainbow Nation he unified.

Since I started frequenting Johannesburg over four years ago, Mandela has often been on my mind, and not only because the ongoing familial battle over his legacy flares up in the media from time to time. Mostly I think of him when I’m running; the place I stay at in Jozi is about a kilometre from his home and my training runs take me past his front door on a weekly basis.

The morning after he died I walked up to his house to pay my respects. The media vultures were already circling, their satellite vans lined up along the jacaranda-lined streets, TV hosts powdering and primping, wielding puffy-tipped microphones, trailed by cameramen.

This I had expected.

It was the mourners that surprised me. Many of my South African friends were shocked to tears when they heard the news, and the city felt like it was running less a cylinder (or two). Even the traffic, renowned for its rude gesturing, tailgating, honking, aggressive drivers, was subdued. So I’d expected weeping and flower laying at the Mandela home, maybe some candles and singing.

When I arrived there was singing, only it was the kind accompanied by hand-clapping, dancing, and lyrics of resistance. A group of about 10 mourners (celebrators?) held aloft a green, white, and black banner printed with Mandela’s face, chanting and singing and dancing in the middle of the street, surrounded by a ring of journalists snapping away with their smartphones and photographers lurching around with their cameras overhead, trying to get the best angle.

Over the course of the day more people would flood in. Some came to lay flowers and candles by the wall surrounding Mandela’s home, but the mood remained celebratory and the singing and dancing continued, spontaneous and unchoreographed. People would stop to watch, or take selfies with other mourners, or join in a round of Nelson Mandela, Nelson Mandela, akekho ofana naye (Nelson Mandela, there is no one like him).

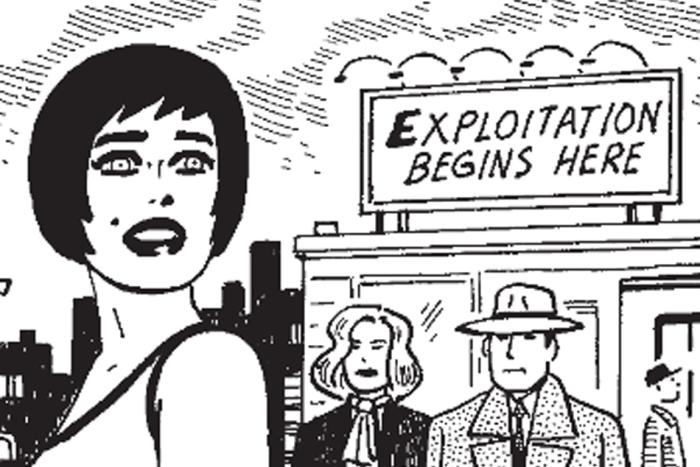

The more entrepreneurial folk walked around offering memorabilia for sale: ribbon rosette framed buttons depicting Mandela’s face, Mandela t-shirts, flags, posters, and framed portraits, all featuring the green, gold, and black of the ANC. Sellers with more inventory lay it out along the narrow strips of lawn on the edge of the street. Others opened backpacks and offered the contents to the mourners walking past.

Perhaps this seems distateful—selling merch at a funeral—but it becomes less so when you remember that part of the reason Mandela is such an icon is because his image has been used for decades as a symbol of resistance, freedom, and equality. Posters, buttons, stickers, t-shirts, and flags played an essential role in the anti-apartheid struggle, not only as a way to spread information but also as a quick identifier and rallying point for those in the same political or cultural camp. The images and colours of these materials were so threatening to the ruling party that many of them were banned in South Africa; posters were smuggled into the country from print shops in nearby Botswana, and from further abroad.

The leader of a movement must be photogenic, dynamic, and have a catchy name. Think Lenin. Think Che. And think Mandela, whose face and name became a shorthand in the struggle for equality. People here grew up carrying Mandela with them physically—they hoisted placards and banners of his face at protests; they wore his image on t-shirts and kangas wrapped around their bodies; and they plastered stickers of his face onto their personal belongings.

In their grief they do the same. The merch makes the man tangible. Like the divvying up of Great Aunt Greta’s china and furniture, it allows mourners to take a piece of Tata Madiba home with them, to hug him around their bodies and commune with his presence.

*

When the stands begin to fill at Soccer City, ANC colours dominate the crowd. Like at Madiba’s home, entrepreneurs turn a brisk business outside of the stadium and many mourners wear t-shirts printed with Mandela’s face, sometimes in black and white but more often on the background of a black, yellow, and green ANC flag. They carry small flags of the same colours, printed with Madiba’s face or the spear and shield logo of the ANC, or wear larger ones wrapped around shoulders and hips. Banners hang from railings, flapping wetly in the misty air.

Down below, the stage and VIP boxes are filled with dignitaries from all over the world, dressed in their finest black. They take turns on the stage at the edge of the pitch, speaking eloquently of Mandela as a symbol of Hope, an icon of Tolerance, a man whose Legacy is distilled into phrases like “fighter for social justice” (Rousseff), or “giant of history” (Obama), or simply “teacher” (Ban Ki-moon), depending on political bent. The divide can’t be more obvious. The leaders are down there; the people are up in the stands.

As the day progresses my head buzzes with crap coffee and questions: Is it ever going to stop raining? (No.) Will Bono play an impromptu concert with Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Charlize Theron on triangle? (No.) Will this event, which brought together an unprecedented 91 heads of state (some whom wouldn’t be caught dead in the same city, let alone the same stadium), and attracted what seems to be all the media in the world, come anywhere close to fully expressing the great loss of a cultural and political giant such as Mandela?

The crowd gives the answer to this last question. It’s jubilant at first, but as the wet morning melts into a wet afternoon and the proceedings continue in a deathly formal march, the crowd grows restless. They interrupt the speeches with singing, only to be reprimanded by the master of ceremonies. They chant and blow vuvuzelas as though at a football match. And when they boo their president, Jacob Zuma, more than once it’s impossible to ignore that many of them are wearing the colours of the ANC, the party he heads.

It’s a pointed message: You are not Madiba. You are not us.

And just like that, a memorial that seemed designed to provide politicians and pop stars an opportunity to say “He was a great man” in as many iterations as possible becomes a venue for the voice of the people. A fitting tribute to the man who freed that voice.