In August 1977, 12-year-old shoeshine boy Emanuel Jaques went missing in Toronto. He begged his parents to let him work on Yonge Street, saying there was more money to be made there than in his neighbourhood, Toronto’s Little Portugal on the west side.

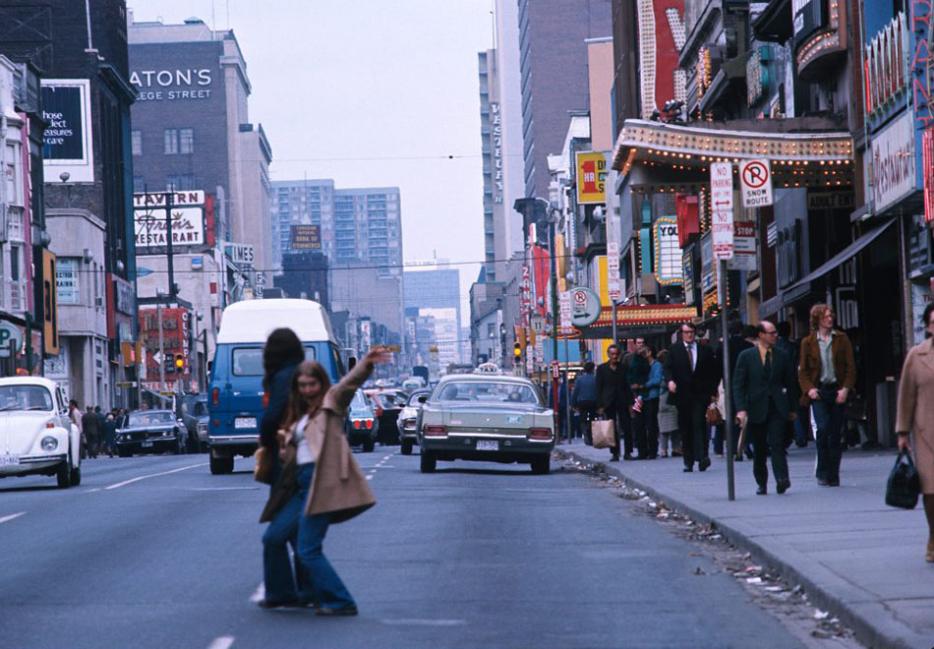

The Yonge Street of the late ‘70s was far different than what we see now: the sprawling Eaton Centre mall had just been built, but it was still considered a dangerous and seedy part of town full of criminals, prostitutes, strip clubs, and drugs. Emanuel went missing for days, setting off a panic in Toronto’s Azorean community. This, after all, was “Toronto the Good.”

Emanuel’s body was found on the roof of Charlie’s Angels at 245 Yonge Street, then a body-rub parlor. He had been restrained for hours, repeatedly sexually assaulted, and then strangled and drowned in a sink. Four men were charged with his murder. In the end, Robert Wayne Kribs pleaded guilty, while Saul David Betesh and Joseph Woods were eventually found guilty in a trial.

There was plenty of recrimination in the aftermath of Emanuel’s murder. Portuguese Torontonians felt that the city hadn’t done enough to protect them. Meanwhile, the city’s gay community, already the target of abuse, was singled-out for blame; as though the entire community was responsible for this senseless and brutal murder.

The building where Emanuel’s body was found has since been destroyed. In its place is a Champs shoe store, right across the street from the Eaton Centre.

In Kicking the Sky, Anthony de Sa retells events of that summer through the eyes of Antonio Rebelo, a 12-year-old boy living in Toronto’s Little Portugal at the time that Emanuel goes missing.

We spoke with de Sa about his real-life experience in Little Portugal that inspired his novel, as well as Christie Blatchford—at the time a crime reporter for the Toronto Star who covered the Emanuel Jaques trial.

Anthony de Sa: I was 11 years old and I was living in the Portuguese neighborhood in Toronto when this occurred. For the most part, I’ve been writing this book in my head ever since I was 11. Trying to make sense of that senseless murder.

Christie Blatchford: It was my first trial. It was a hideous case, of course, and had been very much in the news that summer and the summer before. It was just a very sad case, and it was a complicated case.

ADS: One of the most striking memories for me was hearing my father put a deadbolt on our front door. Prior to that, we had never locked our front door or windows. That was indicative of the fear that everyone was beginning to sense in the neighbourhood. A normally boisterous and very social community went silent. I remember our teachers forcing us to walk in twos to the bathroom.

The Portuguese community felt they had been betrayed. That this bag of goods they had been sold—which was coming to Canada for a better future for their children, like many immigrant communities did—that they had been somehow duped, that this had happened to one of their own. They felt that if it happened to Emanuel, it could happen to any one of their children.

CB: There were four people accused—one of whom ultimately was acquitted, one of whom, midtrial, believe it or not, pleaded guilty, and two of whom were convicted of first-degree murder.

The little boy was killed above a body rub parlor. A rub-and-tug. It was a seedy place, and there were tons of these places at the time, and not just on Yonge St. though many of them on Yonge. They’d grown like a weed in that year and a couple of years before. Yonge Street had become very seedy and unseemly.

ADS: In silencing a child like Emanuel Jaques, it gave birth to a voice in the community that hadn’t been there before. The Portuguese had, for the most part, remained kind of quiet, dutiful citizens, who have traditionally never questioned authority. This murder gave a voice to that community. I think that voice was heard loud and clear the day they all marched in the thousands to Nathan Phillips Square and Queen’s Park. As a kid, it was very uncharacteristic to see people in my community be so vocal.

CB: This was one of those stories which people described—thank Christ I didn’t say this myself because it’s so clichéd—as one of those watershed moments for the city, where the city purportedly lost its innocence. That’s a lot of crap. That’s a lot of not very good writerly exaggeration, but the elements were all there to get a lot of attention. It was an innocent young boy, four creepy guys. It was terribly tragic. Immigrant family, Portuguese family. It just had everything.

ADS: So much was going on that summer. It was the culmination of so much excitement in the city. [The previous year] the CN Tower was topped off, then that April the Blue Jays came to the city. We were going to be a world-class city.

I remember being totally ecstatic. Not that the boy was murdered, but that the murder triggered a kind of parallel to the Son of Sam murders that were happening in New York City, and as a kid, we were fascinated that Toronto had hit the big time by having one of these murders. I know that sounds really terrible, but as a kid in that time and space, it seemed pretty exciting that this was all going on.

CB: It did get a lot of attention by the standards of the day. I covered the whole trial, and the day the verdict came down it made the front page of the Toronto Star. The murder of course brought a lot of attention. But the actual trial coverage, given what we see now, was miniscule. We didn’t cover things like that then. It wasn’t because the case was unseemly, it was because that’s how newspapers of the day covered murder trials. It’s really astonishing to go back and look at it and realize how fucking little play it had. If that case were unfolding now, I bet you, it would be [covered] every day. It would be on the front page half the time, at least.

ADS: What was fascinating to me at that time was there seemed to be this kind of muddling of homosexuality versus pedophilia. That was reinforced by [the singer and anti-gay rights activist] Anita Bryant. During that time she had become very vocal with this Save Our Children campaign. She even came to Toronto in the January following the murder to reinforce the idea or make the connection that gays were deviants and couldn’t be trusted. The gay community was just then coming out of its shell in the ‘70s. This kind of put them back for a little while because it was dangerous out there.

CB: Yonge Street was a drug-shopping mart then and in some ways it still is. It’s still a pretty happening street.

ADS: Yonge Street, I’ll be frank, as a child it was an exciting place. It was neon signs and sex shops and it was just electric. Kids don’t see the grime. And the dirt.

CB: I often walk by the place where the body rub parlor was and remember looking at it back then and being kind of horribly fascinated by it.

ADS: Great cities need to have a little bit of sin. Every fantastic city in the world has that element of the risqué. It was an incredible turning point in the identity of this city: who were we, what did we represent, and where did we want to go.

Image from Flickr

--

Find Hazlitt on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter