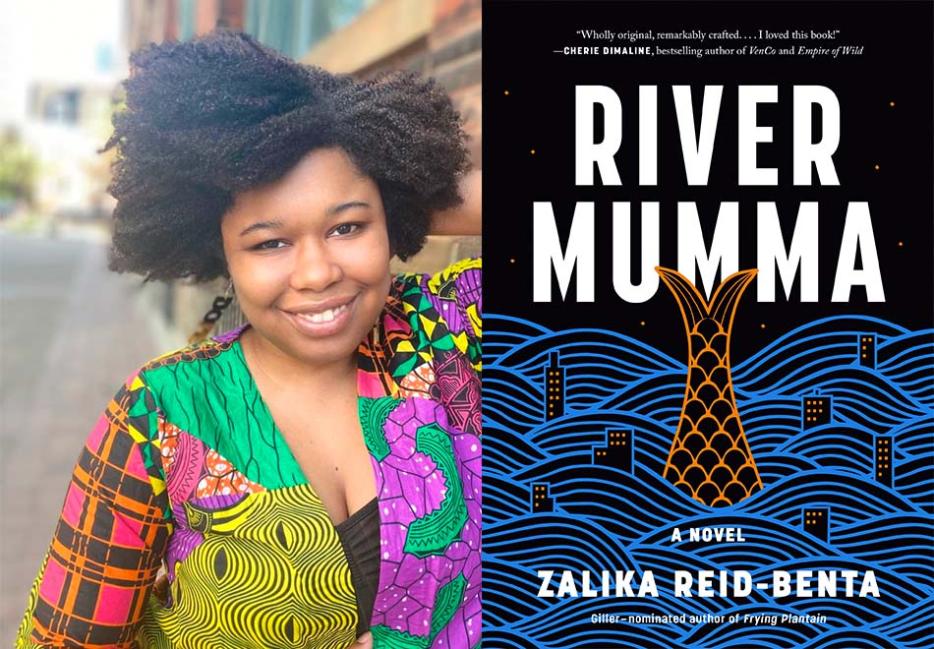

Much like the waters that house her almighty spirit, the titular figure in Zalika Reid-Benta’s River Mumma (Penguin Canada) holds many stories, a host of deities. In the sophomore follow-up to her debut novel Frying Plantain, the author embraces folklore that describes the Jamaican goddess as just one entity, coming to rescue a young Black woman from the lethargy of post-grad adulthood.

Benta grounds her mystical tale in the streets of Toronto, Canada with a vivacious group of characters.

Hanna Phifer: What drew you to write a book centered around River Mumma?

Zalika Reid-Benta: I really like water. I have this thing about water. I love being around water and she is a water deity. I did grow up hearing stories about her, but it was one of those things where I had to research a little bit more because it was kind of said in the background. She wasn’t really spoken about in the way Anansi the spider is spoken about. River Mumma was a little more amorphous. So I always wanted to do something around water, and she’s perfect.

The protagonist Alicia is in the midst of a quarter-life crisis when we meet her. Is that where you were when you began this book?

No, when I began it I was past that point, but I had had another life crisis a few years before. And I remember what that felt like, and I remember feeling lost and feeling like I was never going to succeed or anything. So it didn't take much for me to get back to that place to be able to write that character.

Did spirituality also help you get out of that period?

No, actually. I have a very interesting relationship to spirituality. I’ve always been interested in it and I’ve always wanted to learn more about it, but that wasn’t what happened during that time for me. It’s more of an ongoing experience for me, I would say.

In the book, Alicia’s grandmother is integral to her spiritual development.

I've been interested in the way I see my family or other Caribbean families talk about spirituality or not talk about spirituality. It's kind of just this thing that's around that we don't talk about. It's hard to sort of pinpoint what is actually a ritual and what comes from traditional medicine.

I think it kind of just came together because I thought that it would be a good point to have my characters go through the spiritual experience. It just seemed like it fit with what I was trying to write about.

What I've tried to explore in the book, as well, is that they're reading different things or they're remembering different things from their families. Like, that's a big part of being in the diaspora, especially from countries that have been colonized and where traditional spiritualities and traditional medicine have been demonized because of colonialism.

Can you tell me a bit more about the research you did for the book?

Reading a lot of books, which is why at the end of my books there’s a reading list. It also meant speaking to my family, speaking to my grandmother, speaking to my mother, speaking to my grandparents, and also speaking to my friends about what their families had to say.

Toronto plays a big part in this book. In fact, the book closes with a map of Toronto. Can you explain that?

There was a lot of conversation happening around what it was to be a millennial, and I didn't really agree with the articles I was reading about millennial experience—or not necessarily didn’t agree, but I couldn't relate to it. And there was conversation about Toronto's slang and language, and certain news outlets were attributing Toronto's slang to celebrities instead of where it actually comes from, which is Jamaican patois, and also East African languages.

I was also watching Scott Pilgrim vs. the World and that film is very much based in Toronto. It’s a very different Toronto, but it’s a very Toronto story. And I love the energy. I did my MFA in New York and I read a lot of either manuscripts or books about New York and how New York becomes sort of a character. So that was in my head.