In August, the Little Mermaid, the famous bronze statue in Copenhagen, Denmark, will turn 100. The centenary is apropos, as mermaids are again a big thing. A number of Twilight-like young adult novels, including Carol Turgeon’s Mermaids and Sarah Porter’s Lost Voices, are bestsellers; Animal Planet’s faux-reality TV feature Mermaids: The New Evidence was one of the highest rated programs of the year; and “merlesque” performers—synchronized swimmers in retro-styled fish drag—stage shows across North America and Britain. Unlike the mermaid-worship that accompanied the release of Disney’s blandly friendly The Little Mermaid, the current mermaid trend is dark, sexual, and meshes well with postfeminist ideals. “Mermaids practice more feminine power,” explains Brenda Peterson, author of the mermaid-themed novel series The Drowning World. “Like many female wild animals, mermaids choose their own mates. So mermaids are action heroes in their own rights; they are not just acted upon.”

The new mermaids draw on ancient legends of deadly sea sirens and a broader tradition of the femme fatale. They’re at odds with the Little Mermaid statue, which is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale: a piece of literature steeped in 19th-century stereotypes of women as subordinate and weak. The 1991 Disney film, replete with female < male clichés, is also a version of the Andersen story, though truthfully the original is, at least in this regard, kind of worse. Did you know that at the end of Andersen’s tale, the little mermaid does not get her prince? He marries someone else, and, because of a bargain she’s made with a sea witch, the only way she can avoid turning into seafoam—ocean garbage, essentially—is to kill him. She has the knife in her hand but can’t bring herself to do it. But then, to her surprise, she doesn’t die. Instead, she transforms into a spirit of the air, and she gains something no other mermaid has: an immortal soul. The other air spirits explain: “The mermaid has no immortal soul, and can only acquire that heavenly gift by winning the love of one of the sons of men. Her immortality depends on union with man.”

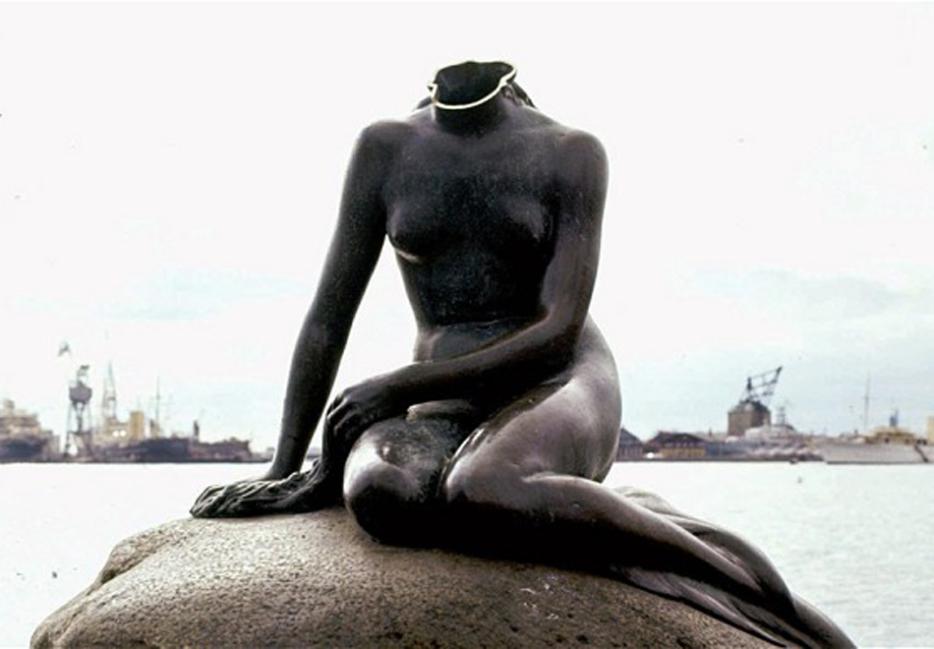

Obviously, this is a crap deal for mermaids, and reveals some fairly nasty assumptions about the relative value of men and women. The Disney film accepts these politics, but softened them for the self-esteem ‘90s by making their mermaid…not empowered, exactly, but “spunky” and self-sufficient. When one’s heroine is tomboyish, smiley, and an excellent reggae dancer (swimmer?), it’s easier to forget that she is willing to amputate her entire lower body to get a boyfriend. Not so with the statue, which is clearly, viscerally vulnerable—not just true to the original tale’s obsession with women as victims; “acted on,” but exaggerating the theme. It is a portrait of femininity at its most stereotypically girlish—slumped, sad, stuck forever on a rock. Accordingly, it is one of the most-defaced sculptures of the 20th century. The Little Mermaid’s head has been cut off twice, her arm has been severed, and she’s been knocked off her rock with explosives. She’s also been attacked by political vandals, both on the right and the left. In 2007, she was draped in a burqa as a protest of Turkey’s bid for inclusion in the EU, and, in celebration of Women’s Day 2006, a group of European feminists affixed a dildo to her hand and covered her in green paint. But people just clean her up and put her back together, and it’s never long before she’s back on that rock. In 2010, Denmark temporarily gifted the statue to the World Expo in Shanghai. “I think they should keep her there,” a 16-year-old Danish girl told a reporter. “She doesn’t represent Danish life in the 21st century.”

Doesn’t she? I think the fact that she keeps getting beaten on shows just the opposite: The Little Mermaid is more relevant than ever. Look at that submissive posture, and the exaggeratedly sad bend of her pretty legs. She embodies a type of femininity that seems fairly universally despised: man-crazed, self-victimizing, and hyperemotional. She is the forebear of so many reviled cultural figures: Lisa from Six Feet Under, Charlotte from Sex and the City, Bridal Barbie; Heidi Montag, Rihanna when she’s apologizing for Chris Brown… on and on. Even Sylvia Plath fits—not the actual Plath of “Daddy, Daddy, you bastard, I’m through,” but the lovesick, jealous, housebound Plath of Ted Hughes’ description: “her main enthusiasm is me.”Stand by your man, etc. Who is actually okay with these women? On OKCupid some men will write “no drama”—the mermaid-way of being is scary because of how quickly it can turn back on them. The Little Mermaid is the archetypal hot-but-crazy ex-girlfriend of douchebag lore. But the same qualities make her a feminist saboteuse, playing to type even though the type clearly sucks, and she has other options. Far from a heroine, the Little Mermaid seems a brainwashed rube who, sitting on a rock, pining for her prince, throws all our hard work back in our faces.

Over the past few decades, it’s said, we’ve expanded the range of acceptable ways to be women. Joan from Mad Men, Ellen DeGeneres, and Hillary Clinton would have been reviled in Andersen’s time, but are lauded as “role models,” with droning predictability, in our own. It’s understandable: the conventional female character was for centuries a weepy doormat, and it’s natural that we’d bristle at more of the same. But then, to stick with the Mad Men analogy, when a character like Don Draper shows vulnerability and sacrifice, we say he’s finally complex: human and thus redeemed. Are we extra-hard on vulnerable women because they’re regressive, or because vulnerability is uniquely human? Both in Andersen’s story and in life, the little mermaid is punished, again and again, for submissiveness but also for audacity: she is a creature who aspires to be human.

In actuality, this striving—for humanness, for knowledge, for mobility—outstrips the prince stuff in Andersen’s story. Before we hear the stand-by-your-man garbage from the air spirits, there is a much more provocative passage from the Little Mermaid’s POV:

“Human beings became more and more dear to her every day; she wished that she were one of them. Their world seemed to her much larger than that of the mer-people; they could fly over the ocean in their ships, as well as climb to the summits of those high mountains that rose above the clouds; and their wooded domains extended much farther than a mermaid’s eye could penetrate.”

There are cringey moments in Andersen’s tale for sure, but there are also ones like these that complicate them, and therefore, the ending, with its pat prescriptions of feminine duty. This complexity is understandable: critics are now discussing how Andersen may have been gay, and a theme of outsiderness, as well as forbidden and dangerous love, runs through his work. These themes apply to the question of femininity as well, not least in The Little Mermaid, where the bloody terms of the heroine’s bargain—in exchange for legs, she carves out her tongue, and every step she takes feels like walking on a “sharp sword”—literalizes the major risk of women doing anything but what they were told to do in 19th-century Europe. Seen in this way, the stakes of the little mermaid’s dilemma seem heightened. Her vulnerability actually looks like courage, her slumped sadness becomes something of a challenge. A kind of gutsiness emerges, and while it’s vaguer—and thus more difficult to cheer on—than the winky kitsch of merlesque, and the deadly powerful sea sirens merlesque invokes, I think it’s also more interesting. We forget, sometimes, that to be totally self-sufficient and femme fatale-ish, to never wind up “acted on,” is also a dehumanizing cliché.

The Little Mermaid statue may seem one-dimensional and regressive, but it is tinged with the ambivalence of the original story—hence, I think, our intense reaction to her. She may be boy-crazed and angsty, but she’s also tenacious. When one group dismembers her, another puts her back together, and when she’s defaced with paint, people just clean her up. Apparently there are four copies of her stored in different secret spots around the world, just in case. Like our feelings about her, the Little Mermaid is impossible to kill.