When civil rights heroine Rosa Parks died in 2005, she was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in Detroit in a small mausoleum. Soon after, the cemetery’s owners raised the prices of nearby crypts from $45,000 to $60,000. “You get to be buried with Aunt Rosa for a price,” said her angry nephew at the time. It’s a fact that the famous dead provide economic benefits, not just to cemeteries, but to the local economy: Post-Mortem Fame drives tourism. People who want to see Rosa Parks’ last resting space, to get close to her hard-earned aura, will spend their travel dollars in Detroit, rather than Disneyland or Florida’s Gulf Coast. This is just simple commerce at work: celebrity endorsement increases market demand, even, it turns out, when the celebrity is dead.

Consider the case of Richard III, late of a parking lot in Leicester, UK. First they found the body. Then began the bidding war over the bones. Where should the last Plantagenet king be buried, for keeps this time? The decision was left to the university that made the discovery. Both the Richard III Foundation and the Friends of Richard III Society made the case for burying him in York, according to the king’s own wishes. He was, after all, known as Richard of York, not only by historical record but also from the schoolroom mnemonic for remembering the colours of the rainbow: “Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain” (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet). But Jon Ashworth, Labour MP for Leicester South, cited the finders-keepers rule: Richard died at Leicester (in the Battle of Bosworth Field), was buried in Leicester (at least for a spell), he should stay in Leicester. Besides, Ashworth told the House of Commons, re-burying the remains at Leicester Cathedral would “hugely benefit” the local tourism trade. The university agreed. Leicester will have its king. Hotels will adjust rates accordingly.

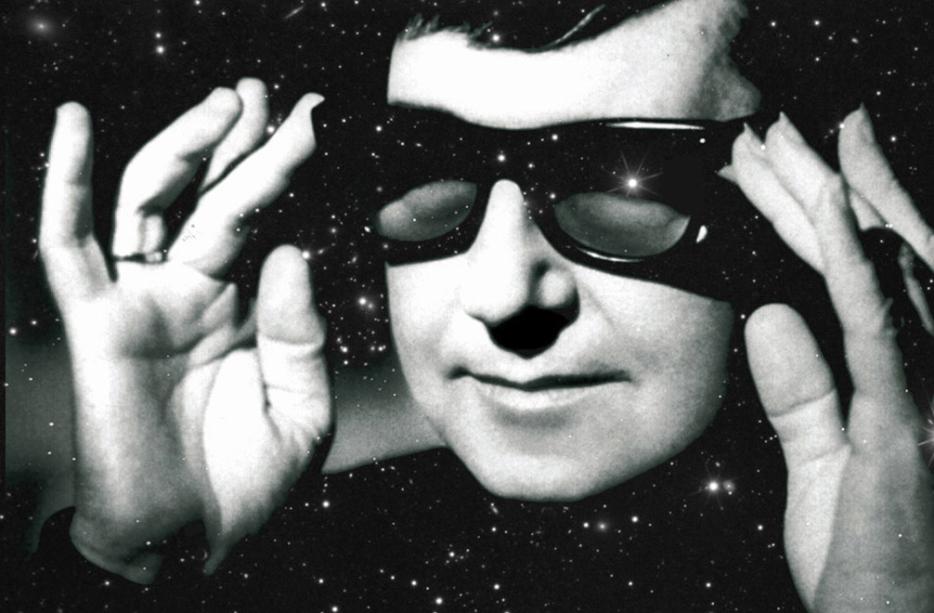

I first became aware of the phenomenon of Post-Mortem Fame when I visited Los Angeles in 2007, while working on a book about the funeral trade, or the “deathcare” sector as they like to call it. In Los Angeles there are as many stars under the soil as above. Over a million people a year visit Forest Lawn in the suburb of Glendale where Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Sammy Davis Jr., Errol Flynn, Walt Disney, and Michael Jackson share 300 acres of greenspace with Larry Fine of the Three Stooges and so many others. There is a gift shop. On the afternoon I visited Westwood Cemetery in Beverly Hills, the small grounds, bordered by glass condo buildings, were busy with visitors looking for Dean Martin, Truman Capote, and Rodney Dangerfield (whose tombstone reads, “There Goes The Neighborhood”), but mostly for Marilyn Monroe. Frank Zappa is there too, somewhere, but his grave is unmarked. I’ve since learned from the website ehow.com how to find it: eight yards due east of Roy Orbison, apparently.

“Gravehunters” treat their subculture as kind of a morbid scavenger hunt: they compile wish-lists, take photos of tombstones and markers, post tips and directions for other gravehunters on blogs. At Westwood, I followed a family to Marilyn’s tomb where they laid down pink roses. Her crypt is covered in lipstick kisses. I touched her name on the plaque. This, I thought, is as close as I’ll ever get to unalloyed fame: within an inch of solid marble. It’s absurd of course, but I wondered if this might be the secular equivalent to communion with holy relics, the bone chips and garment shreds of the saints. Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable represent a time when fame glowed at its brightest, compared to now, when fame is diluted by sheer volume and turnover. In Los Angeles, dead stars of a certain time and class still bear the aura of permanence.

Right now cemeteries are in trouble. The rise in cremation (68.4 percent in Canada) means more people are being scattered or inurned than buried. Demand is low. This is why the industry talks of creating “living spaces” in cemeteries, to drive human, breathing traffic to their gates and to create buzz. So Hollywood Forever cemetery in Los Angeles holds nighttime concerts (Sigur Ros, Flaming Lips) and screens movies on the wall of the mausoleum: people bring blankets, picnics, wine, watch the film, confront mortality, go home (and create buzz). But the main draw for Hollywood Forever, as with Forest Lawn and Westwood, are its fallen but not forgotten stars: Valentino, Cecil B. DeMille, Tyrone Power. Since 2002 Karie Bible has led tours of the grounds, always dressed in vintage black gothwear. The most popular stop is the cenotaph for Johnny Ramone, a likeness of Johnny with a guitar that seems to emerge from stone as if from a pool of water. Dee Dee Ramone is just across a reflecting pond. When I visited his grave, after waiting for three young men in do-rags to pay their respects, I found a black tombstone with the Ramones logo also covered in lipstick kisses and surrounded by sun-bleached teddy bears, votive candles, a woman’s dress pump. Epitaph reads: “OK... I gotta go now.”

In 1998 the owner of Hollywood Forever, 28-year-old deathcare whiz-kid and technical advisor to the TV series Six Feet Under, Tyler Cassity, told the New York Times that it was his dream to repatriate the remains of Doors singer Jim Morrison from Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, where he was quietly buried in 1971. It was known that Père Lachaise had grown impatient with Morrison’s pilgrims and the mess they left behind, the graffiti and impromptu shrines, and Cassity had hoped they might do a deal. “We’d give him a special area,” he said. Hollywood Forever was looking to draft a big name corpse, the way hockey teams draft franchise players. The Paris deal never happened, but Cassity made it clear he was open to negotiation with other stars, including those who were still alive. “Right now, we want to create a place that would correspond to their aesthetic,” he told the Times. “We’re not trying to court them directly, ambulance-chase. We would have loved it if Frank Sinatra would have come here. But he didn’t.” Sinatra was buried at Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and a pack of Camels. His headstone reads, “The Best Is Yet To Come” and his grave is a few hundred yards from Sonny Bono’s.

England may sneer at the customs of the colonies, especially when it comes to death and ritual, and the business of gravehunting. Evelyn Waugh’s novel The Loved One was a not-so-veiled broadside at the gaudy exhibitionism of American deathcare, in particular the tombstone kitsch of Forest Lawn in Glendale. But commerce is commerce on both sides of the Atlantic. Ashworth is right: if the point of death tourism is to feel the frisson of permanent fame, we can assume Richard III will draw pilgrims to Leicester. People will want to stand close to the last Plantagenet. No doubt Leicester Cathedral will sell postcards and War of the Roses liquid soap dispensers.