It’s no great trick to touch the dead. What you need is the right apparatus, which is the logic behind the séance: the medium can read signals in what is, to the rest of us, garble. She tunes them in like a radio, to use a concept dreamed up by British author and artist Tom McCarthy. It’s simple physics: the total energy in an isolated system remains constant over time, so, the dead leave a revenant (heat, magnetic energy, something electrical) that can, in theory, be measured. Energy doesn’t disappear but is converted, and if the theory holds, we expect it can be un-converted through some “software” (Madame Whoozitz and her crystal ball) that operates by spooky algorithm. That’s fun, or unsettling, depending on your faith and emotional wiring.

My guess is that it’s not easy, or we’d all be haunted all the time: while shaving or opening a can of soup. Some places, no doubt, are more receptive than others. On the prairie you can hear radio stations from Texas bounced off the ionosphere. Maybe that’s why prairie towns are more haunted by those other signals than, say, Toronto or Montreal, where there’s too much static. I think Winnipeg is a particularly strong receiver.

On Halloween in Winnipeg kids dress in orange and poppy-red and Scream masks, and then cover it all up with winter coats. They work the more fertile neighborhoods of River Heights and Wolseley like gleaners in a wheat field, harvesting candy: sure, it’s fun, but there seem to be heavier presentiments in play as well, as if they feel something. Grown-ups hand out Tootsie Rolls in acts of ritual appeasement. Owls fly low in cemeteries and at Oak Hammock Marsh, a nature preserve north of the city that hosts pumpkin carvings, as close as you can get to pagan sacrifice. Halloween is a kind of secular Passover: follow the protocols, hope for the best, spirits move on.

I’m not from Winnipeg but spent five winters there, long enough to feel a particular brand of death-awareness: there are more funeral homes in Winnipeg than Starbucks. In 1998 there was trouble at the Elmwood Cemetery. Bank erosion exposed a stretch of property and threatened to send caskets sliding into the Red River: 108 graves had to be moved. This was discussed in town, I’m told, not as an infrastructure problem but as folklore: that was the year they wouldn’t stay buried. W.G. Sebald wrote in The Emigrants, “And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” a reference to 20th-century European history and the Freudian return of the repressed. It is a suitable motto for Winnipeg.

“I came away with the conclusion that Winnipeg stands very high among the places we have visited for its psychic possibilities.”

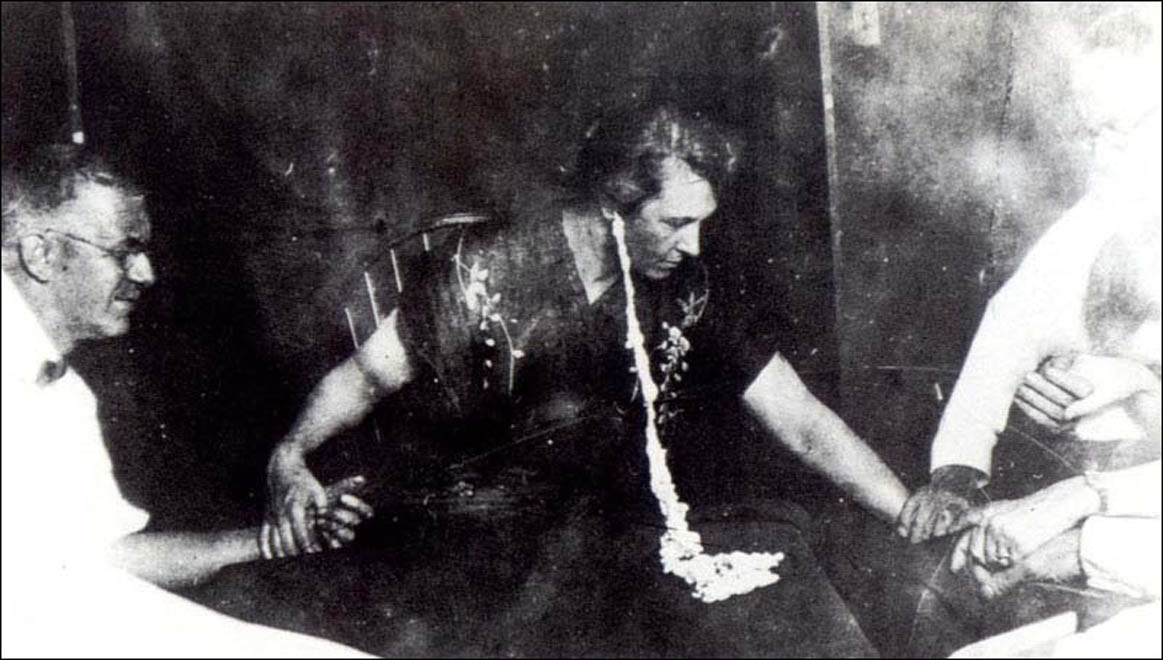

The city used to be a transportation hub, Chicago of the north, and then trading lines and commercial preferences changed, leaving behind a rusty ribbon of neglected railway lines: a ghost of global capitalism. Appropriately, Winnipeg was also a hub for psychic activity in the early 1900s, thanks to the work of Thomas Glendenning Hamilton, a surgeon, school trustee, Liberal member of the Manitoba Legislature, and séance impresario. In 1919, after one of his twin sons died, Hamilton began to experiment with Ouija boards and table-tipping, the well-known method of decoding messages from the dead through the kitchen furniture: one called out letters of the alphabet, and when the table tipped, one moved on to the next letter until sentences were revealed. His Scottish nanny, Mrs. Poole, turned out to be a skilled table-tipper.

Not that Dostoevsky was picking on spiritualists (he was in fact picking on the dogma of the Roman church), but the point applies: is knowledge of life after death liberating, or does it lock you into some horrible box? Here’s your eternity: millennia of tipping over other people’s tables at parties. Easier to think of death just as another measurable quantity, like the movement of planets or energy in a closed system, and, presumably, plenty of Hamilton’s séance guests saw it this way. Grief helps tip the balance, too. People just wanted to know that their sons were safe.

It matters that Hamilton found spiritualism after his son died. As Tom McCarthy points out, Alexander Graham Bell had made a pact with his brother: if one of them died, the other would invent a device capable of receiving messages from the dead. The brother died. Bell invented the telephone. McCarthy is mad for ghostly communications and codes begging to be cracked: in his art, he plays at the idea of repetitive radio messages from the underworld, like the cryptic threads of poetry in Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée: radio that can only be heard by tuning between the stations. The hero of his Booker-nominated novel C is a heroin-addicted wireless operator in the Great War, who winds up at a séance only to reveal it as a sham: the hoaxers used radio-controlled gizmos to make the tables tip. Underneath it all is a whopping dollop of French Theory: the closer you look the less you see, or the closer you look the quicker you uncover the lie. McCarthy says we live in a frantic mess of signals, but we decide how to decode them. Hoax or miracle? It’s up to you. If you want to hear the dead in the white noise, to know they are safe and playing chess with Napoleon or whatever, that’s what you’ll hear: grief is a sharp tuning instrument.

What was the lie in Glendenning Hamilton’s work? Study the pictures. Or just click through them, same outcome. Chilling, in some cases beautiful (the 1934 picture of a woman named Mary M., back arched on a couch, looks like a Henry James character who’s fallen into an F.W. Murnau film), they’re full of holes: the ectoplasm pouring from poor Mrs. Poole’s mouth and nose is either gauze bandaging or crumpled tissue paper in which cut-out photos of faces have been glued. Those skilled in spotting cheeseball Photoshop effects need not even break a sweat. In one case you can see the smiling face of Arthur Conan Doyle who, the story goes, returned to Winnipeg in 1931, the year after he died, coming out of Mrs. Poole’s nose.

Who’s the hoaxer? In Dostoevsky fashion, we’re not meant to know. Enough that Glendenning Hamilton, one-time head of the Canadian Medical Association, made this his life’s work after his son died.