The 1971 film Duel, Steven Spielberg’s second feature, is a 90-minute car chase. Dennis Weaver is a travelling salesman driving through the California desert. He stops at a gas station to call his wife, who is still mad at him for ignoring the fact that a friend made a pass at her at a party. Back on the road, tail between his legs, he is soon followed, too closely, by a tanker truck blowing black smoke which then proceeds to stalk and threaten him for the rest of the picture. Pick your metaphor, Spielberg makes it easy: the truck represents sexual guilt, or the Republican nightmare of moral decay, or better yet, a betrayal of the American promise that no malevolent force can come between a man and his one true love, his Plymouth Valiant. Spielberg remade the film four years later, swapping out the truck for a shark.

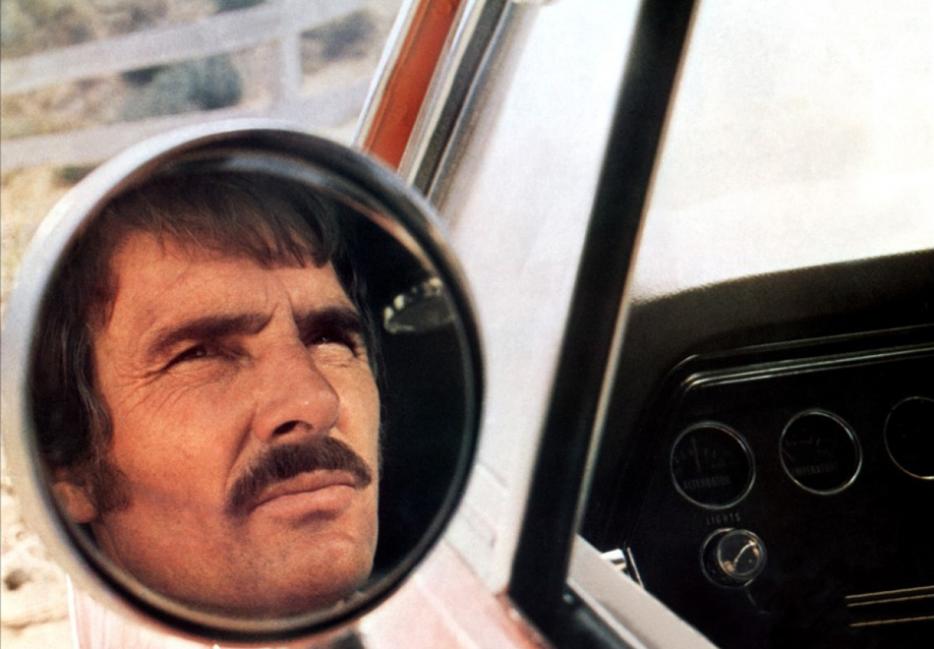

Jaws is the better film, but Duel has its place in the canon of films about the fetishization of the car, alongside American Graffiti and Cannonball Run, which tell us that men and women (mostly men) accomplish things behind the wheel, that a car can deliver the most ephemeral of modern goals: a destination. Purpose replaces fear, which is left behind like forgotten luggage. The long-distance driver has the sense of being invisible and untouchable: trouble recedes in the rearview mirror. There are films that poke fun at this romantic notion, like Monte Hellberg’s Two-Lane Blacktop, made the same year as Duel, in which Warren Oates, James Taylor, and Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys contrive to race from New Mexico to Washington, D.C. for “pink slips” (ownership of the other’s car), but get so completely caught up in their own obsessions, lies, and anxieties that they, and the movie, seem to forget why they’re out there in the first place.

Sample dialogue:

Oates: Well, here we are on the road.

Taylor: Yup, that’s where we are alright.

It’s a Beckettian road caper. Likewise, in Carnival of Souls, a 1962 B movie by Herk Harvey, whose only prior experience was as a director of instructional filmstrips, we see Mary Henry driving to a new life as a church organist in Utah after a horrible trauma: she was in the losing car in a drag race that wound up in the river. Two other girls were killed in the crash. Now, alone on a dark highway, fiddling with the radio, she’s startled by her own reflection in the car’s side window. Then, her reflection morphs into the ghostly face of a man who seems to be trying to tell her something. This face will haunt and taunt her in her new life until she thinks she’s going insane. “If she’s got a problem,” says one of the locals, as she leaves her home town, “it’ll go right along with her.”

That’s the clip that opens the video for the Pere Ubu song “Road to Utah” from the new album Carnival of Souls, a vivid musical account of what lead singer and songwriter David Thomas is obsessed with right now, which includes the false promise of the American highway. Pere Ubu was formed in 1975 in Cleveland, and for over 39 years has somehow managed to resist commercial failure despite all frantic attempts to embrace it. Thomas has described Pere Ubu’s sound as “avant garage,” to the relief of music writers in need of concision: aggressive rhythms, strained vocals in the Captain Beefheart ballpark, poetic prophecy. Thomas sounds like an unmedicated Tom Waits without the coy, performative irony. “Irony is the refuge of the weak-willed and timid,” says Thomas. In other words, whatever it is that he’s saying in his music, and it’s not always clear, at least he means it.

So take him at his word that Carnival of Souls the album is not about Carnival of Souls the Herk Harvey movie. “The album,” says Thomas on the Pere Ubu website ubuprojex.com “is ‘about’ a complex sensual response to living in a world overrun by monkeys and strippers who tickle your ears, cajole you to join in with their cavorting and then become vindictive when you decline… I got rid of my phone because I don’t want them calling me.” And yet, the music matches the film in theme and tone: creepy, feverish, conducive to troubled sleep and formally rigorous. So the album may not be about the movie, but it seems to be chasing the movie for its own dark reason.

In the song “Dr. Faustus,” an old man sits on his porch on Route 322 south of Meadville, in the Pennsylvania rust belt, watching the traffic. Thomas has been here before, both with Pere Ubu, and with his own musical side-project, the Two Pale Boys, which put out a live album called Meadville in 1997. Meadville is a town people drive through to get somewhere else. You can ignore it but, as Thomas sings in “Dr. Faustus,” it won’t ignore you.

“He sees you but you don’t see him

Maybe speeding past, sixty miles an hour

He can see you

and he can see your hopes, and dreams, and fears,

trailing behind you like scraps of paper that have been torn from a map.”

He is the ghostly face in the window that Mary Henry sees on the road to Utah. She may think she has escaped a nightmare (it gets worse, but see the movie yourself, it’s on YouTube), invisible and untouchable as long as she’s on the road and moving faster than her own fears can follow. But she’s been witnessed, by a ghost, by the old man, who knows that she can’t escape, that terror follows her like paper scraps or the demonic tanker truck in Duel. “I am damned,” sings Thomas, “to almost see what could have been.”

The car is an emotional cocoon. Roland Barthes said that cars are the modern equivalent of great gothic cathedrals, “conceived with passion by unknown artists,” he wrote in Mythologies, “and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a magical object.” Which may, if I can peg down the metaphor, be overdoing it, at least in a modern context: prophets like Thomas and Barthes, and to a lesser degree Spielberg and Monte Hellman, wag a finger at us for treating cars like fetish objects, but I think that time has passed, and it’s too bad. In high school I drove a Pontiac Parisienne the size of a fishing boat. By the end there were holes in the floor on the driver’s side big enough to put my feet through to touch the road, Flintstones-style. The cigarette lighter was used not to charge devices but to light cigarettes. I felt safe in there.

Now, no one, except for a few romantic holdouts, sees the car as anything other than a necessary nuisance to be installed into daily traffic. People don’t get behind the wheel to outrun their troubles anymore, they do it because mobility is an urban necessity and public transit is hobbled. It’s a quaint idea, to drive for any reason other than to get to Staples before it closes. That’s a problem. There’s no shortage of things to fear, but we’re running out of places in which we feel safe.

The Lost Library: forgotten and overlooked books, films and cultural relics from Tom Jokinen’s overstuffed Ikea bookshelves.