My nani was born in Lahore. As a child, whenever I stumbled upon this fact, shelved neatly away in my mind, I would pick it up gently, like a dark gleaming jewel, examining it from all sides. What made the stone precious I couldn’t exactly say, but I didn’t doubt its value. It had a distinctive sheen. But then again, so did many things about Nani.

When I was young, Nani—my mother’s mother—was the grandparent I gravitated toward. For an “old” person, she seemed the least old. She frequented cinemas, often alone, for every “mirch-masala” Hindi film released, and bought me their cassette soundtracks for my Walkman. Banned from Bollywood myself till a more suitable age, I would hang on to her every word as she detailed the plots.

During summer holidays, Nani would take me in autorickshaws to the library near her North Bombay apartment, where I would stock up on Sweet Valleys and she would buy bindis from the neighbouring store. A chain smoker all her life (which was neither common nor respectable for women of her generation), she would spend inordinate amounts of time on her tiny fourth-floor balcony, from which, in the distance, the Arabian Sea was visible. She wore variously patterned silk and cotton saris, and equally vivid lipstick. One of my childhood best friends and I have always maintained that the only person who could pull off scarlet lipstick was Nani Kaul.

Why, then, given Nani’s dazzling persona, was it her place of birth that persisted in my mind? After all, to be born in Lahore in 1934 was simply a fact. But by the time I was my nani’s granddaughter in the ’90s, it felt more like a myth.

*

In 1947, two hundred years of colonial policies and their polarization of Hindus and Muslims—who had lived intertwined lives for centuries before British rule—combined with the ambitions of political leaders and came to a head. With the end of British governance, the Indian subcontinent was partitioned to create the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. British barrister Cyril Radcliffe was brought in to oversee the entire process: his lack of knowledge about India was seen as advantageous by the collapsing empire, which was suddenly in a hurry to shut shop. By bringing in Radcliffe, Britain signalled that they sought a quick “impartial” resolution to Partition, so as to coincide their own departure from the subcontinent with the second anniversary of Japan’s World War II surrender. They wanted to leave as an imperial power, not bow to the wishes of a colonized people.

The province of Punjab, in which the city of Lahore lives, was split in two. Amid religious riots, fear, and poor governance, ten million refugees fled their homes over just a few short days, travelling by train, foot, and bullock cart. In what was the largest forced migration in human history, Hindus and Sikhs travelled east, to “India,” and Muslims to the west, to newly formed Pakistan. Over the course of Partition, including that of Bengal to create East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), nearly two million people died. That literature, art, cinema, and songs from South Asia continue to speak of Partition today is hardly surprising: it is a wound we never healed.

By the time this took place, Nani had long since left Lahore—whose multicultural, Muslim-majority borders and gleaming architecture eventually belonged to Pakistan—and moved to Lucknow, where she completed her education.

I don’t recall hearing any stories from her childhood, but in contrast, I remember being told several by her mother—my great-grandmother, who we called Amma—about her own. Amma would recount vivid scenes of growing up in the 1920s and ’30s in a girls’ boarding school run by Irish nuns, and later in a British-administered college. In one, Amma and her Indian friends responded to a national call for purna swaraj, or “full self-rule,” by sneaking up to the roof in the dead of the night with an Indian flag. They proceeded to lower the Union Jack and replace it with Gandhi’s spinning wheel, risking beatings, and worse, expulsion. To me, it felt like Enid Blyton, where midnight feasts were replaced by acts of resistance.

But it was only recently, while talking with my mum about her family’s past, that I learned Amma’s infamous boarding school was located in Lahore. For I’d only known it as being in “India.”

Nani went on to do a master’s in English literature (she had wanted to do it in Hindi, but her father had deemed it pointless) and then marry my nana in 1957. Eight years later, they moved to Bombay with their two small children, my mother, and my uncle. Lahore may have seemed, by then, like another world.

I can’t remember when I began to feel that Nani’s birthplace was “different” than Nana being born in Delhi, or Dadi—my father’s mother—being born in Sawantwadi. I imagine it had to do with going to school and being exposed to ideas about Pakistan as treacherous or inherently “different” that I would never have encountered at home. The jigsaw, when I tried to assemble it in my mind, was misshapen. Pakistan, an alien land. Nani, lipsticked and vibrant, born in Lahore. Me, connected both to her and to this shadowy place. I couldn’t make the puzzle pieces fit. But when I was with Nani, her soft skin and delighted laugh, the picture was always whole.

I never asked her how she felt about her place of birth or if she ever wanted to return—or how she felt watching yet another Bollywood movie depicting Pakistan as the invariable enemy at the gates. For if Partition was a wound, we didn’t try to heal it. Instead, it was gouged and salted with nationalism: a common purpose to unite against. Cross-border love stories were positioned on-screen as exceptions to the rule: a triumph against all odds, with the Indian army making a righteous, narratively confusing appearance.

It wasn’t just cinema. Ever since I can remember, “Go back to Pakistan” has been a common and senseless refrain used to cultivate anti-Muslim sentiment in India. As though Pakistan, of which we were so recently a part, where my grandmother came from, is the furthest from India you can be.

*

On August 22, 2022, the government of Pakistan declared a state of emergency: over a third of the country, an area equivalent to the entire United Kingdom, was underwater.

The summer had been scorching, with April and May bringing severe heat waves, drought, and forest fires. Combined with the rising temperatures of the Indian Ocean, one of the fastest warming in the world, the intense buildup of heat meant that when the monsoon finally arrived, it didn’t provide relief for the parched land and its inhabitants. It brought chaos.

It rained and rained, with some areas of Pakistan seeing a 700% increase in expected rainfall. Simultaneously, glacial flooding began in the north, where more than seven thousand glaciers provide water for the country. Now they became a deluge.

Thirty-three million people were affected, half of whom were children. Eight million people were displaced, and over two million homes were destroyed, to say nothing of farmland, livestock, and belongings that some of the poorest people on the planet had spent generations acquiring. Over seventeen hundred people lost their lives.

I sat on my mum’s rocking chair, dry and safe during our own comparably manageable Indian monsoon, watching the news: People and their pets struggling to stay afloat, buildings filling up fast with water, rescue helicopters unable to take off. Families drinking water contaminated by dead cattle. Parents unable to find dry land to bury their children. I felt paralyzed in front of the TV, my blood running cold.

I am not a newcomer to climate change. In 2008, I won a closely contested seat on my student council, running in large part on a climate platform. That same year, I attended climate camp in Kent, a direct action protest against a new coal-fired power station. We were trained to remove our SIM cards before attending planning meetings, and police helicopters patrolled overhead day and night—a tactic to prevent us sleeping. To me, this precious Earth has always been worth fighting for.

But watching Pakistan filling up with water, the desperation and hopelessness of so many millions of people, was the first time I physically, bodily, felt the weight of the climate crisis. Dread crept into my every pore. It felt like it was my home underwater—wasn’t it?

*

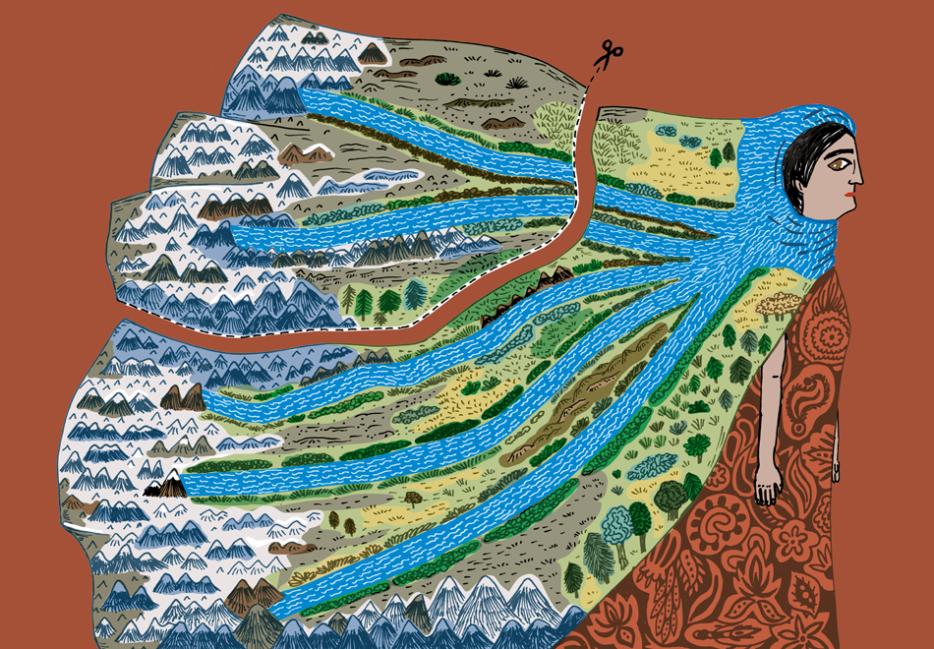

Punjab gets its name from paanj aab: it is the fertile land of five rivers. The Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej are all tributaries of the mighty Indus, which hosted one of the world’s earliest civilizations, and from which India derives its name. These rivers originate at different points in the Himalayas, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush mountain ranges; most travel through Kashmir before merging into the Indus, which eventually flows into the Arabian Sea.

In many ways, my ancestors followed a similar trajectory. In the early eighteenth century, large numbers of Kashmiri Hindus migrated to the plains of Punjab, Delhi, and other northern provinces. At the time there was no India, Pakistan, or British rulers. Instead, these regions were part of the Mughal Empire.

After Partition, the snowy province of Kashmir, which initially chose to remain independent of both nations, acceded to India in a messy, reluctant affair. War between India and Pakistan broke out almost immediately. A UN ceasefire deal allocated parts of the princely kingdom to each of the two countries, but unrest in the region, including an unrelenting occupation by the Indian army, continued.

The newly formed de facto borders also meant that all five of the Punjab’s main rivers, as well as the Indus into which they flowed, now came through India before entering Pakistan. In 1948, India shut off water to Pakistan at two junctures, and a decade later, the Indus Waters Treaty was signed, which gave control of three rivers to Pakistan and three to India. The pact has held till now, though whether that is in part because India hasn’t run out of water yet remains to be seen.

Rivers and people have always flowed in criss-crossing ways, moving and being moved by internal and external forces. But when national narratives wilfully forget these entanglements, when the flow of water and people is stymied, it creates a division—not just of the land, but in the mind. Kashmir doesn’t just keep the two countries in a state of perpetual cold war, but looms large in India’s national imaginary: a pristine land that must be defended against “invaders” at all costs.

Who are these so-called “invaders”? My nani, born in Lahore, now Pakistan, could perhaps be classed as one. But in a twist of irony, she is a Kashmiri Hindu, the very community that India claims to defend—that it uses to justify aggression toward both Pakistan and Muslims within its own borders. I can recall several moments during the past ten years of Hindu right-wing rule in India when I’ve presented my ID to authorities—with the Kashmiri caste marker “Kaul”—and received a comment or expression of misplaced solidarity.

We are, apparently, the furthest from Pakistani you can be.

*

Pakistan is the world’s sixth most populous country, but contributes less than 1% of global climate emissions. The ice-capped Hindu Kush and Himalayan ranges below which Pakistan lies are known as “the third pole.” Like the Arctic, these glaciers are melting at an unprecedented pace, a direct result of emissions from hyper-industrialized countries. Combined with oceanic heating, this leaves Pakistan as one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. It is also one of the planet’s poorest nations, unable to cope with the devastating effects of policies and practices not its own. When UN Secretary General António Guterres visited Pakistan in 2022, he said that in all his life, he had never witnessed the scale of climate catastrophe he saw there.

The rivers that came from Kashmir and wound their way through a once-unified Punjab had overflowed their banks on Pakistan’s side of the border. One in seven Pakistanis was affected by flooding, and an entire year later, 40% of children living in flood-affected areas were still facing hunger, with girls bearing the brunt of malnutrition. Writing in 2023, a doctor in the province of Sindh found that children were lucky if they ate once a day. With agricultural lands submerged, six million people who lived crop to crop, with no savings to fall back on, were pushed further into poverty.

In August 2023, Pakistan flooded again. It wasn’t as severe, but having just experienced the most expensive climate disaster in human history, the country had barely begun to repair itself. One and a half million people had been living in relief tents for over a year, and were faced once again with rising water levels.

In March 2024, while I was working on an early draft of this essay, unexpected rain and snow hit Pakistan, causing both floods and avalanches. The Grantham Institute on Climate Change in London said that the “fingerprints” of global heating were clearly visible in Pakistan, while another report found that the country’s floods had been made 50% worse by global emissions (notably, not Pakistan’s own).

Meanwhile, on the ground, the most vulnerable Pakistanis are facing an “unending cycle of displacement and despair.” Many have never managed to return home, and others who did had to flee again. Their farmland, their only source of income and food, is under severe threat. The expression “climate anxiety” is said to describe what many people feel today. But now, I’m not sure I ever understood what it truly meant.

In 2022, Pakistan pleaded with the world. Its prominent novelists wrote op-eds in the West’s most prestigious newspapers. Its diaspora took to social media, highlighting unfolding travesties. A devastatingly poor country that emitted a negligible quantity of greenhouse gases was drowning. Aside from homes, schools, and roads, the country needed to rebuild its health and agricultural sectors, and huge portions of its drainage system. Pakistan needed not just help, but reparations.

In news footage from the time, Pakistan’s minister for climate said, looking directly into the camera: “I am confident the world will listen—it can’t be so unjust.”

Can’t it?

*

When Nani died, I had just entered middle school. My journal entry reads:

I can’t believe it. Life is so weird. I can’t imagine that Nani is dead.

She takes me to the library, cooks me food, gives me money on my birthday, talks to friends, comes with us to the beach, fights with me and so much more. It is impossible to believe I will never ever do those things with her again.

I couldn’t fathom it. I write that again and again in different ways: “I can’t believe it.” It was the collapse of a key section of scaffolding that made up my idea of home.

It is the loss of home which feels impossible to comprehend or bear—and the fear of this loss that makes us feel like we should do everything possible to preserve it.

When Pakistan flooded, India did not feel that way. When the Indus River, which flows through Indian-occupied Kashmir, was turned into a lake over one hundred kilometres wide in parts of Pakistan, it wasn’t our problem. That wasn’t our home. And if India, so very recently a part of the same land through which the same life-giving river flows, where so many of my generation’s grandparents were born, could adopt this attitude of indifference, what hope did Pakistan have for receiving justice from the rest of the world—from England, whose two-hundred-year occupation of South Asia divided land and people, impoverishing and polarizing us for their extractive gain; from the United States, the second-largest emitter of global greenhouse gases, whose early backing of Taliban fighters changed the landscape of Pakistan forever?

The novelist Mohammed Hanif writes in the New Yorker: “Perhaps the West fears that if it acknowledges any debt to a country like Pakistan, it will no longer be able to withhold what it owes its own citizens.”

What do we owe, and to whom?

Global warming has a future-tense feel to it. The worry is often for the sort of world we are leaving behind for “our children.” But the stark reality is that over half the world is experiencing dangerous effects of the climate crisis right now, and that millions of children already don’t have a future. This is rarely the focus of “climate anxiety” as we commonly conceive of it today.

Home is how we belong in the world, the harbour to which—if we are lucky—we return time and again. Home is therefore also grounds for empathy and action: who we consider “ours” is who we extend a lifeboat to.

I know this to be true because it took Pakistan flooding for me to wake up, deep in my bones, to the climate crisis. It felt catastrophic precisely because it was so close to home—close enough that two generations ago, it was home. The women of Pakistan look like Nani, they look like Mama, they look like me.

Nationalism is founded on a tightly regimented idea of home, and then feeds off a fear of its loss. In order to address the deep inequality of the climate crisis, in which the people who bear the least responsibility for greenhouse gases are suffering their most devastating consequences, our idea of home needs to urgently and radically change.

For who we consider to be ours and our responsibility can’t just be people who look like us, or whose lives resemble our own. This is not only the fairest way to address the climate crisis, but the only way to halt its death march. For as long as the Western world and the Global South’s elite continue to perform a wilful forgetting of the ways in which our histories and presents are deeply entangled with those who are suffering climate catastrophe right now, we consign action to the future, to when it will affect our children. Of course, by then, it will be too late.

Exploring multispecies justice, Donna Haraway writes: “We become-with each other or not at all.” She terms the entanglements between human communities and nonhuman lives as “holding the unasked-for pattern in our hands.” Whether we like it or not, whether we asked for it or not, we are all tied to each other in criss-crossing weaves of people, rivers, migrations, plants, histories, both intentional and unintentional change.

Learning how to proceed can feel like an impossible task. But when I look at my middle school journal mourning Nani, when I read that the Indus River was born before the Himalayas rose up, when I see growing calls for colonial climate reparations, I begin to hope that in this thoroughly enmeshed world, the answer is not all that elusive. We can’t and don’t need to start over. We are already holding the pattern in our hands.