I was sitting on a train, travelling from my home in Poughkeepsie to New York City, when I saw a note on my phone asking me to write the piece below. I began thinking of a painting, a portrait of his father painted by the Indian artist Atul Dodiya, but the other memory that came to me was that I had long ago been sitting in the same Metro North train bound for New York City when the idea for my new novel, My Beloved Life, had been conjured in my mind. During that journey—I’m talking now of something that happened nine or ten years ago—I was reading Denis Johnson’s marvellous novella Train Dreams. It tells the story of an American railroad worker at the start of the last century. Train Dreams is a slim book but it has the feel of an epic. Maybe that fact had also inspired me.

I asked myself, what would the story be like if this ordinary man had been born not in Idaho but in India? My father was a small boy when India became independent from British rule. He had been born in a hut in a village in India’s poorest province. His life had gone through many changes, and it struck me that in telling the story of a single, seemingly unremarkable life, one could possibly be narrating the story of nation or an entire century. The idea formed in my mind even before I had left the train that I would one day write about my father.

1.

A novel is by its nature fiction but what happens when you put a photograph in it? A photograph is seen as having a documentary status, and it could be argued that it introduces the sense of the real, or of the non-fictional, in a novel’s pages.

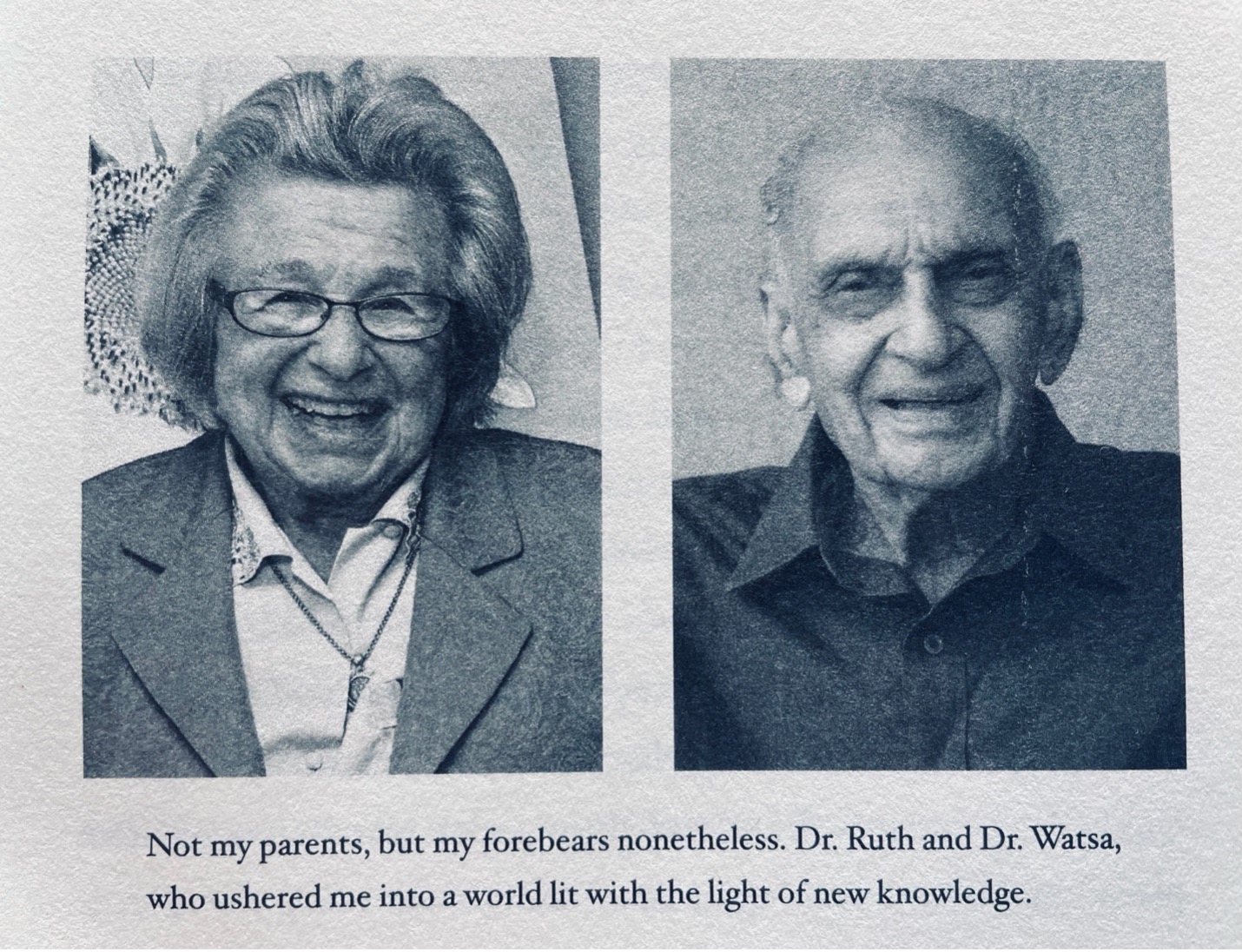

Near the beginning of my novel Immigrant, Montana, a young immigrant from India in the 1980s hears Dr. Ruth on the radio. My narrator was new not only to America but to that foreign land called adult sexuality. The first photographs in the novel were the twin portraits of the sexpert Dr. Ruth and her Indian counterpart Dr. Watsa.

My caption for the photographs returned the reader to what is the work of fiction, a certain play, creating a world of make-believe. My protagonist’s declaration that Dr. Ruth and Dr. Watsa were, in a sense, his real parents was a work of imaginative refashioning.

2.

2.

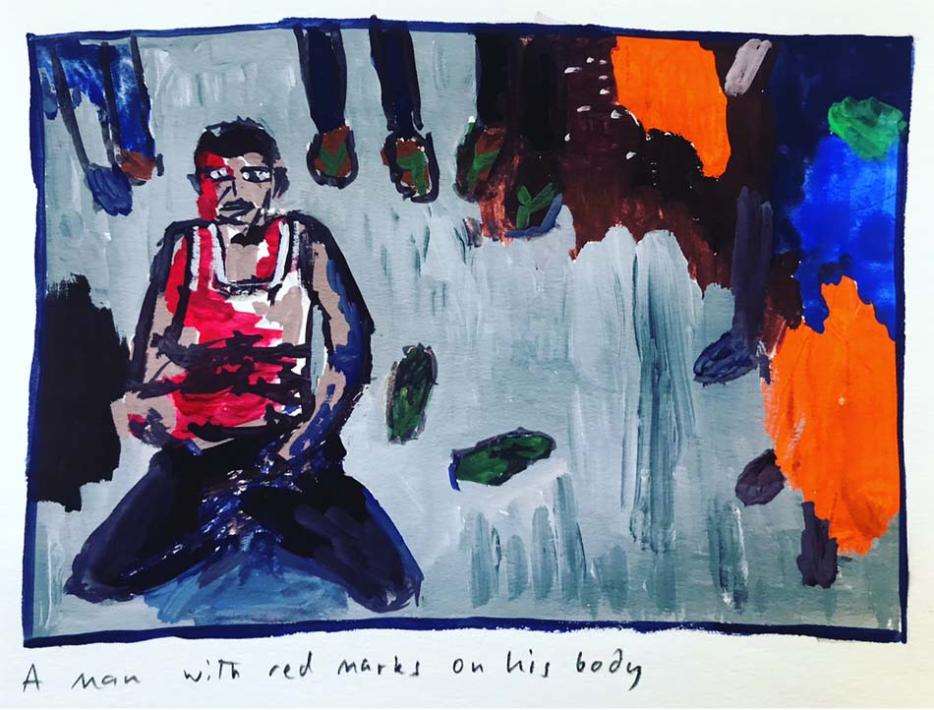

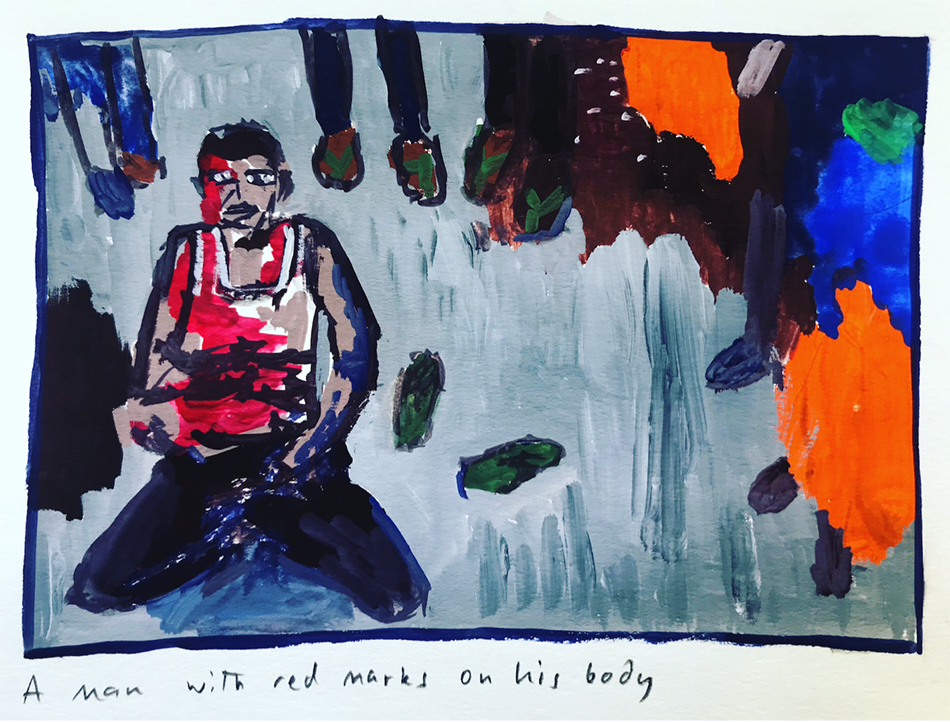

By the time my next novel, A Time Outside This Time, came out, I had been making watercolours. I had been moved by a photograph I had seen in an Indian newspaper—moved enough to want to paint it. The newspaper photograph showed a man kneeling in the dirt, begging for his life. Half of his vest—and his face—is soaked in blood. He is surrounded by onlookers—we see their legs, not their faces. The man on the ground, who has not been lynched yet but will be soon, is Mohammed Naeem. He is suspected of being a kidnapper. He is asserting his innocence, because that is the truth, but it is already too late for the truth.

In making a painting from the photograph in the newspaper, I was trying to look at the scene more closely. And perhaps make others do the same.

The above words belong to my narrator but, of course, they are also mine. That novel was about the spread of misinformation. In trying to understand the role of fiction in the age of fake news, I didn’t think novelists needed to go back to facts. Instead, we had to alter our relationship to what is taken as the truth. Introduce ambiguity where there is a terrible, authoritarian certitude. My narrator asks a question: “Why must one slow-jam the news?” and his answer is: “Because all that is new will become normal with astonishing speed.” It is my opinion that W.G. Sebald’s use of old, smudgy photographs and postcards that had been Xeroxed and made less legible was aimed at this ambiguity. He was destroying the link between visuality and truth even as he was reaching for and employing the visual artifact in his work.

3.

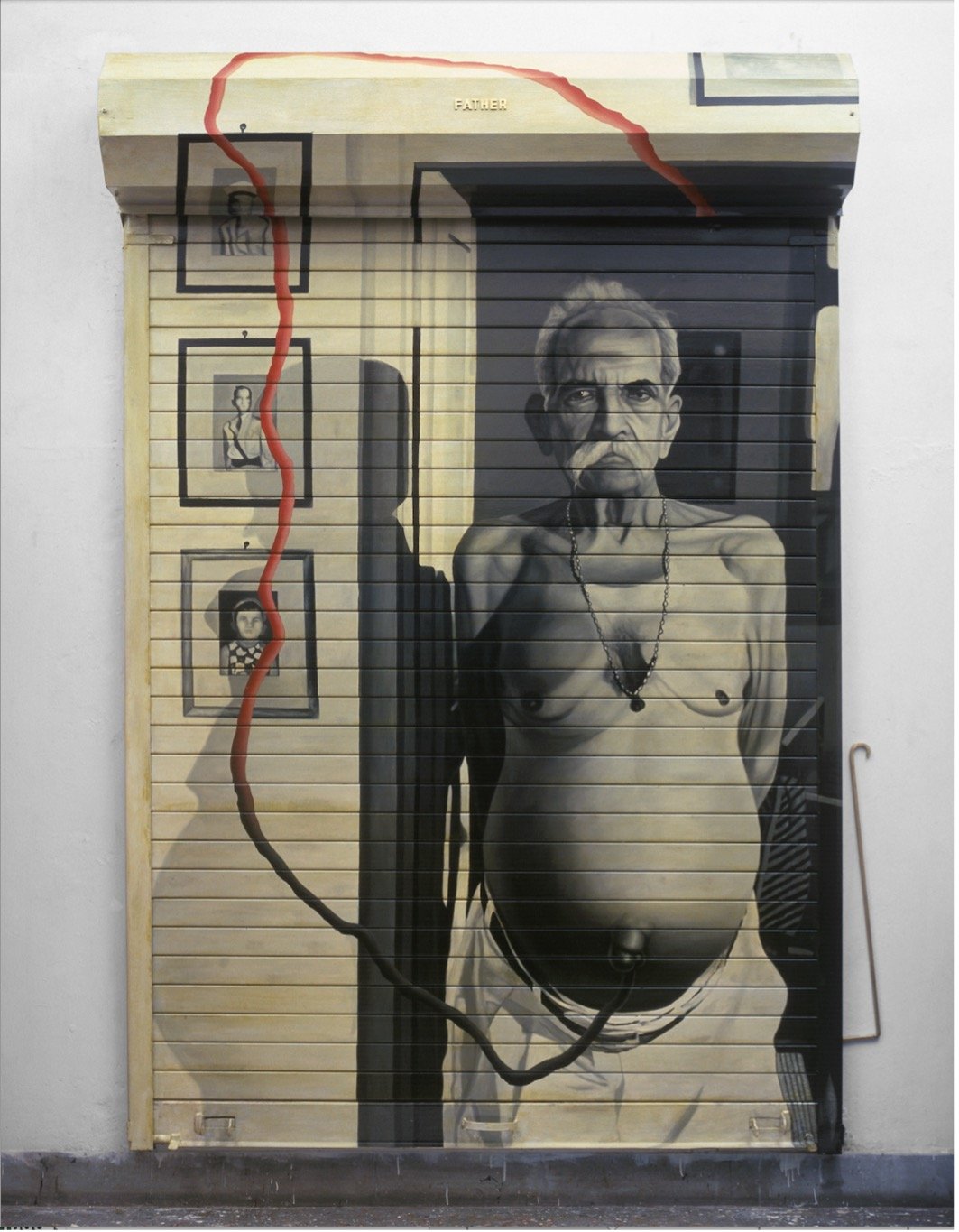

In recent times, when I visited my hometown, and went for a walk near the house where I had grown up, I could see from the startled expressions of people that they had mistaken me for someone else. No, not someone else—they had mistaken me for my father. My hair had turned greyer than my father’s and, for a moment or two, such was the degree of resemblance between us, it was easy to confuse one for the other. I had a sharp sense that I had grown old and that my father would soon die. Maybe this was only a fear but it had settled as a preoccupation. Then I happened to see a painting by the well-known Indian artist Atul Dodiya, a portrait of the artist’s father. And my first thought was, When I write a book about my father, this will be the cover!

In Dodiya’s striking painting, simply titled “This Is Father,” the painter’s gaze is direct and the subject returns the look with equal directness. I say that the painter’s gaze is direct because his look is unsparing, he paints his shirtless father in a naked light, as it were. He captures his age, his gauntness, his paunch. Even the choice of his palette, a near-depiction in black and white, seems designed to promote a way of seeing that is starkly real. The father’s look is equally direct, he meets the painter’s eye in a straightforward way. The father doesn’t smile; he isn’t here to charm or seduce. What you see is what you get. We could say that his look is accepting, neither aggressive nor evasive. The painting shows us a man who is looking with a calm objectivity not at us but at death itself.

A remarkable feature of the painting is the tube that extends out from the father’s abdomen. When Dodiya made this painting his father was in his early eighties and suffering from an enlargement of the spleen. His belly would get bloated and Dodiya would take his father to the hospital to get the fluid sucked out. When I first saw this painting, my father was also already in his eighties. I was very conscious of his mortality. Recently, Dodiya told me that his father was a civil contractor. He used to say that to construct something is difficult and takes time while to destroy takes no time at all. The most tragic event of his life, Dodiya’s father believed, was the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. In 1999, Dodiya started work on a series of paintings about Gandhi called “An Artist of Non-Violence.” His painting of his father was executed in 2002.

4.

A friend made a post on Facebook about a book he was reading. Ashok Lavasa, a top bureaucrat in India, the head of the national election commission, had written a book about his father. The book was titled An Ordinary Life. My friend’s post asked, what was it that made ordinary lives worth telling? Lavasa’s book hadn’t engaged in any name-dropping, it had no stories of decisive moments in a nation’s life and his own role in them; it only offered stories about the father, stories that had passed unnoticed by all. An example presented by my friend in his Facebook post: the father is standing at a railway platform with his young son, the author of the book, who is only nine years old. The father is anxious because his other child, his thirteen-year-old daughter, has been admitted to the local hospital. She is suffering from pneumonia and her life is in danger. The boy is to be dropped off in another town at a boarding house; that is the reason why they are at the railway station. The father resolves his dilemma by asking a stranger, a fellow passenger on the train, if he will please take the child to the boarding house. The stranger says yes and the father rushes back to the daughter. The boy who grows up to become the head of the election commission is telling the story of his father’s faith in humanity. This is one meaning of an ordinary life. I copied down this post and read it over and over again. I was thinking about my own father. Even if you come from a poor background and you have led a life of limited means, do you not deserve a story of your own?

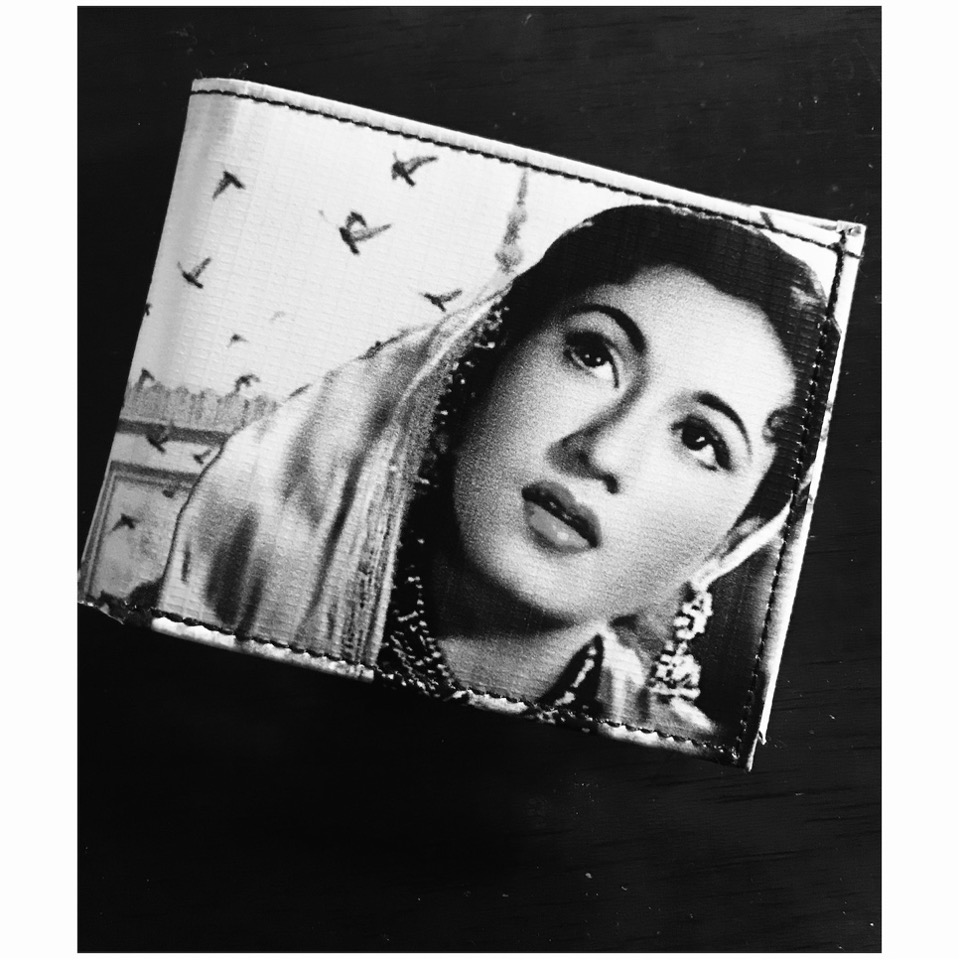

The privilege of writing a novel is that you make up things. I borrowed from my father’s life—his birth in a village in India, his life in a nearby obscure town which has the distinction of being George Orwell’s birthplace, his interest in writing history—but I was inventing details on every page. Did my father have a crush on Madhubala, a popular Bollywood actress of the 1950s? In a playful gesture, would a man like my father be given a gift two or three decades later, a wallet with a picture of that actress on it? I certainly thought it possible and put the picture of such a wallet in my novel. The wallet was real but because the circumstances described in the novel were imagined, I felt I was smuggling contraband in from the realm of the actual.

5.

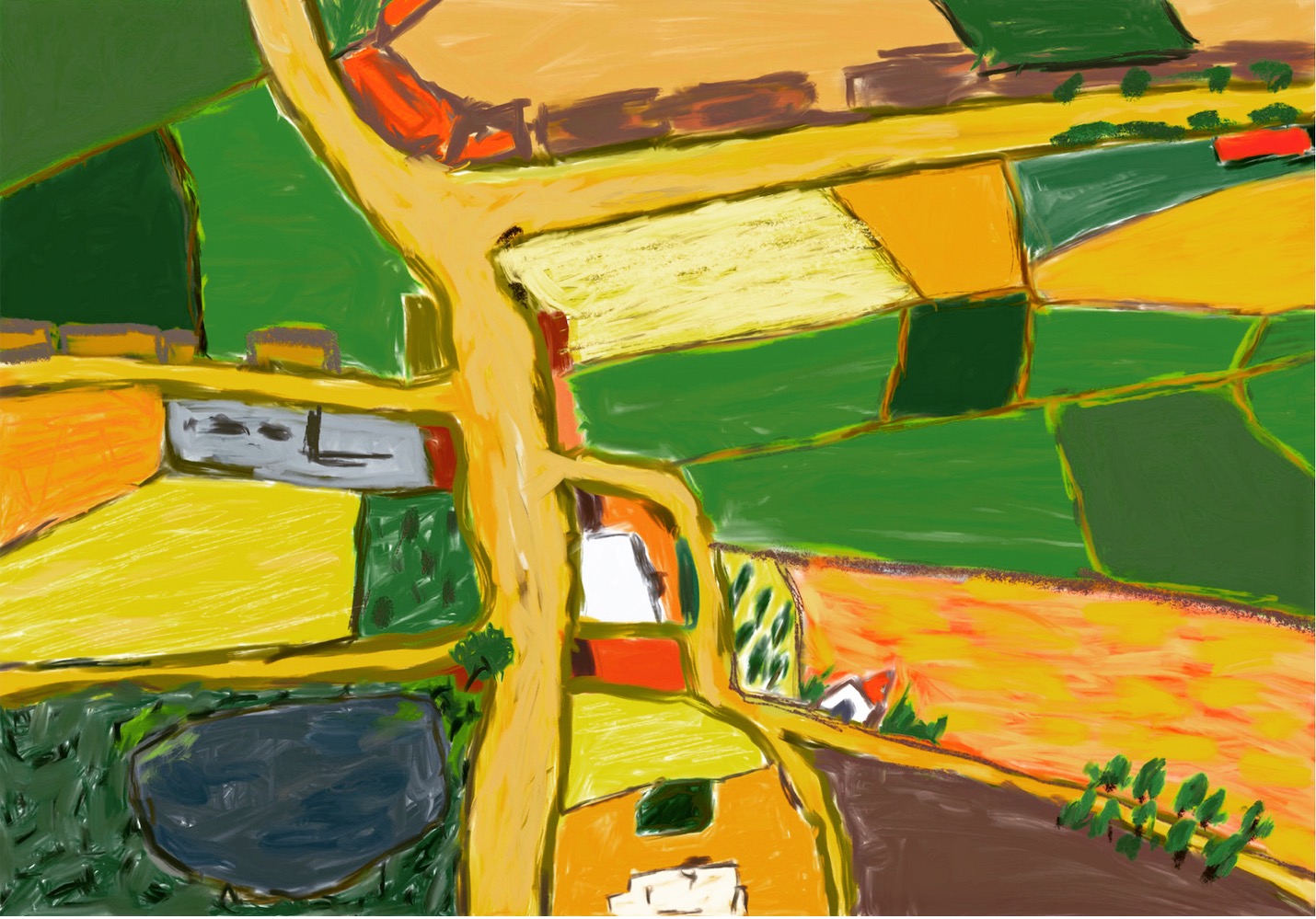

In the summer of 2021, I heard my novelist friend Claire Messud read out an essay at a workshop where we were both teaching; in the essay, Messud described her father drawing on a piece of paper a map of his native Beirut. He was drawing the map from memory; a perfectly accurate map of a city where he had grown up but not visited for decades. At that time, I was midway through writing My Beloved Life, and I came back that night to my hotel room and made a drawing of my ancestral village. As the months passed, the drawing led me to new thoughts. (I’m telling you this because I want to explain process, a visual prompt leading to narrative discoveries.) I had discovered a story about a teacher in Georgia who, when his memory began to slip away, started drawing fantastically accurate maps of the route he took to his school and of other places that were a part of his routine. As my story evolved, I also had the father in my story drawing a map of his village. The father in my story has one child, a daughter, and she notices that the map her father has drawn is only of the village as it was during his childhood. Her father hasn’t included any of the places that have come up and changed during his daughter’s lifetime. A map of a remembered village. It is an accurate map but an outdated one.

6.

It was important that the story of the teacher who drew maps was from a place near Atlanta. I liked this because the daughter in My Beloved Life lived in that city and worked as a journalist for CNN. In trying to imagine the stories this journalist would cover, I found other images. For example, a photograph of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. visiting the Gandhi Memorial on his visit to India. The detail that had caught the photographer’s eye in the MLK photo showed the reverend removing his shoes before walking on to the Gandhi Memorial. (MLK had said: “To other nations I might go as a tourist. To India I go as a pilgrim.”) It was an unconventional image, a distinguished foreign visitor, taking off his shoes out of respect for local custom. How would Indians of different generations respond to this? I wanted to use the MLK photo to show my characters’ attitudes.

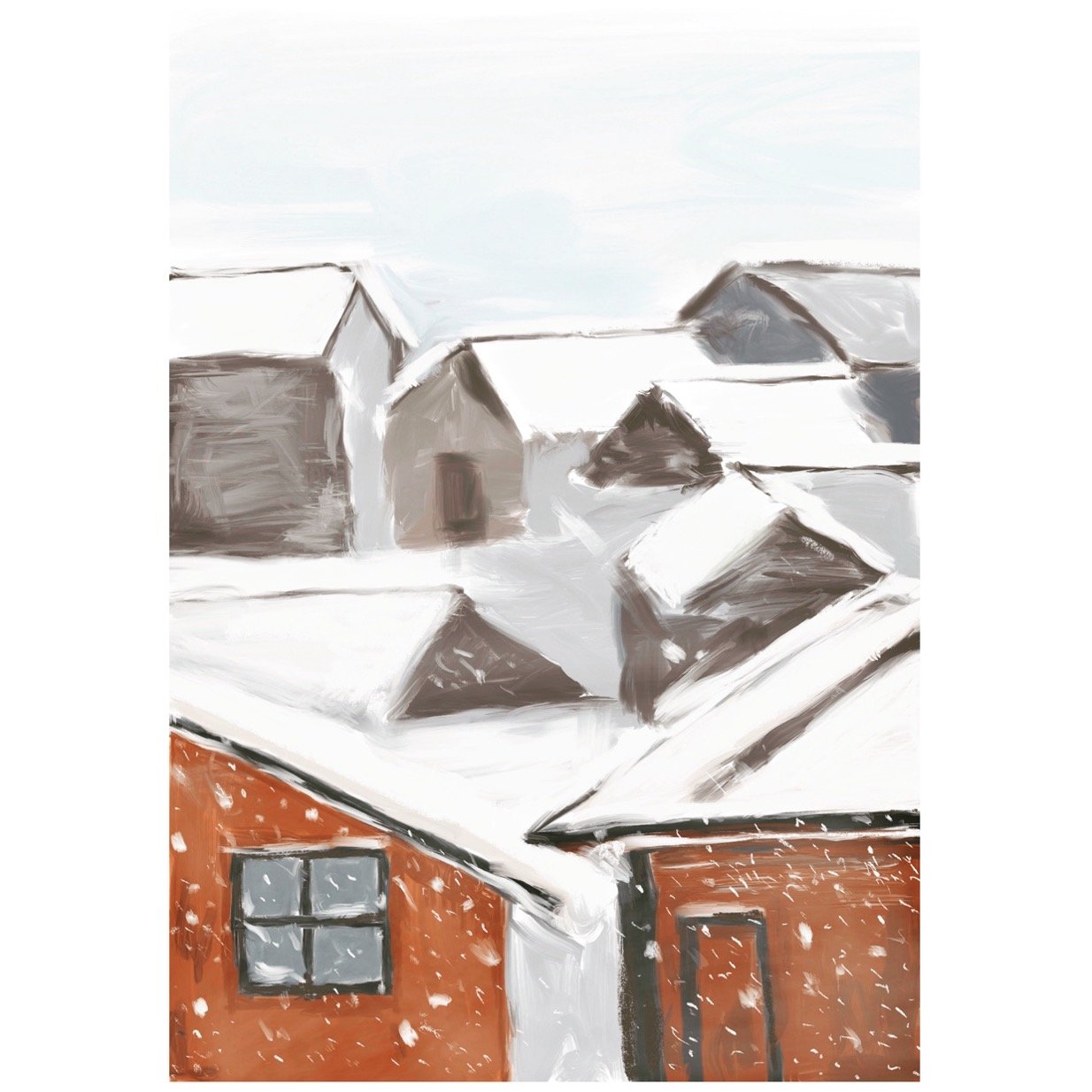

I also found out that at least two dozen Black children were murdered between 1979 and 1981 in Atlanta, and that James Baldwin had written a journalistic report about these murders that was published as a book in 1985, The Evidence of Things Not Seen. In his report, Baldwin had focused not so much on the deaths as on the conditions of the murdered kids’ lives. While researching Baldwin’s writings, I came across an essay by Robert Reid-Pharr in the Berlin Journal that described a teacher’s memory of the young Baldwin in high school. The teacher had asked his pupils to step up to the blackboard and describe a scene from nature. Baldwin chose a winter scene and wrote on the board about “the houses in their little white overcoats.” The image was so striking that when I read it, I thought I should immediately make a drawing. See below. But, dear reader, of all the images I have presented you so far, images that were a part of the thinking about the novel and writing it, how many of these images do you think made it to the final version of the book? Please go on reading to find the answer.

7.

Dodiya’s painting of the aged father, his body connected to a tube, had given me a sense of focus. I could imagine a man dying. The painting provided direction to my writing as I imagined an old man on his deathbed during the pandemic. The images, particularly the one of the film actress Madhubala, were ways for me to introduce an element of whimsical play into the story that I was telling. However, to be honest, I was unsure about the rest of the images. I didn’t have the kind of conviction I had possessed when I had put my painting of Mohammed Naeem’s lynching in my last novel. My editors in the US and in Canada politely but quite clearly suggested that they were not convinced that an honest narration of stories about ordinary lives needed the distraction of pictures. I hesitated a little bit but this was only because in any other context I would have argued that images, deployed in the right manner, open up a reflective space for the reader. But I quickly made up my mind and deleted all the images you have seen so far.

The only image that is present in My Beloved Life is that of a screengrab I had made. A journalist in Lucknow tweeted about his falling oxygen level. He had repeatedly appealed for help but none came. His last tweet was sent when his oxygen level was down to thirty-one. Then, nothing.

I had gone back to facts. In the face of the Indian government’s assertion that it had done everything it could to fight the pandemic and that there was enough oxygen for all who needed it, I felt I needed to tell the truth even though my book was fiction. Fiction because my character reads the tweet and calls her boss at CNN, Roberta, and Roberta tells her that Christiane Amanpour was in London and it was likely that she would catch a flight to Delhi. Would Amanpour really be going to India to report on the second wave of COVID? It appeared unlikely. My character has this realization in her head:

While Roberta was talking, I could suddenly see Amanpour standing on a boat on the Ganga, the burning pyres of Varanasi behind her, the posh accent delivering news about the fresh 200,000 cases of coronavirus in the country.

Instead of Amanpour, it is my co-protagonist who goes. All of this started with the above tweet that I had read, in real time, by the doomed journalist Vinay Srivastava. In using the image of his tweet I was trying to report on an ordinary life and what sadly for many was an ordinary death.