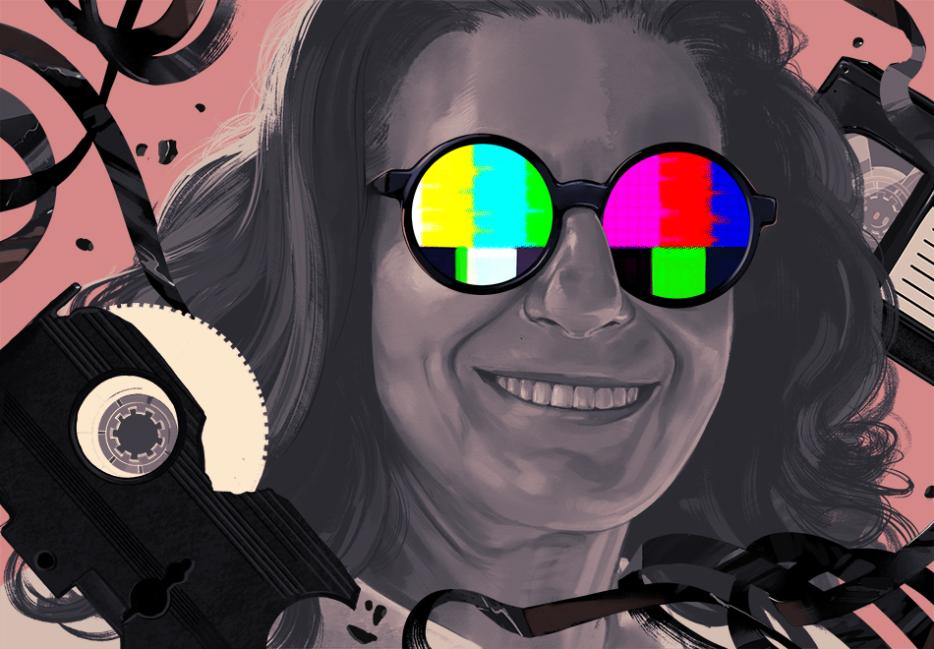

In 1986, seven female independent filmmakers from five different countries came together to interpret the seven deadly sins for a film called Seven Women, Seven Sins. In preparation for filming Anger, New York-based filmmaker Maxi Cohen placed an advert in The Village Voice that read, “ANGRY ? ? ? ? WHAT MAKES YOU ANGRY? I'M MAKING A FILM ABOUT ANGER. PLEASE CALL 976-5757.” She made a second casting call on a local radio station. The host said, “I think you picked the right city. New York is the anger capital of the world.”

Cohen interviewed her ad respondents on BETA-SP, a then cutting-edge Sony camcorder, resulting in a collection of narrated traumas: a young woman with white-blonde curls recites the details of being raped and, years later, stabbed, expressing a wish that all the evil in the world be concentrated on her attacker; a couple who loathe each other but can’t afford to stop living together form a wall of hateful noise; a man in sunglasses recounts murdering four people. The most remarkable aspect of these interviews is the accepting calmness in Cohen's voice. “I do feel like I speak to people's higher selves, and hope that I create a safe space so that they can honestly reveal them,” she says. “When you see a documentary, sometimes it's hard to realize that it's just as much about the filmmaker. Somebody else might get different responses or not as much openness. It's my nature that makes people feel comfortable and safe and open.” She is not intimidated by bearing witness to these raw stories.

Cohen’s flair for gathering confessions from everyday people is a constant in her films. Second Grade Dreams (1983) is, literally, a collection of seven-year-olds relaying their dreams. Intimate Interviews: Sex in Less Than Two Minutes (1984) features women talking about sex. Las Vegas: Last Oasis in America (1982) brings together a patchwork of eccentric Vegas characters, including kids with sage insights on gambling. Birty: Godmother of Watts (1994) is a moving portrait of a Black 50-something foster mother in Los Angeles who has suffered several lifetimes worth of state-inflicted losses to her family, yet persists in caring for the vulnerable, including two drug-addicted babies.

Much of Cohen’s work blurs the line between fiction and documentary. In Boney (1982), Cohen's long-time collaborator, and a spoken-word artist in his own right, Joel Gold, improvises an outsize character walking the streets of New York. The Edge of Life (1984) is metafiction chronicling a day in the life of a video artist with a striking resemblance to Cohen, filmed in her own SoHo studio. How Much Is Really True? (1989) features Cohen herself as one in a group of four women who take a trip to the beach.

Sometimes Cohen invites members of the public to enact her filmmaking ideals. In South Central Los Angeles: Inside Voices (1994), she gives cameras to members of the Black, Latino, and Korean communities who lived and worked in the areas most affected by the 1992 LA riots sparked by the police killing of Rodney King, a Black man. The camerapeople embed themselves within their own communities and the combined footage is a panoramic people’s history of a major moment in US civil unrest.

The Belgian auteur Chantal Akerman also contributed to Seven Women, Seven Sins (she was Sloth). Akerman’s death in 2015 brought on retrospectives that included screenings of the film, which, in turn, led to renewed interest in Maxi Cohen's body of work. The majority of Cohen’s films had been made using magnetic video, a medium that formed the basis of grassroots political and artistic filmmaking from the ’60s until the ’90s but is now more or less obsolete. “We had been asked by curators to do this retrospective of all my work and it really wasn't available,” says Cohen.

Established filmmakers are more likely to have the financial means or machinery in place to preserve their work for rediscovery and retrospective. Artists putting out work on niche formats, who are relatively unknown, are more likely to lose it to the whirligig of life. The possibility of a legacy is weighted towards those whose interests dovetail with market forces at a crucial moment in their creativity.

Is it up to an individual to try to secure their legacy? Or must they succumb to luck and collective impulse, as unfairly stacked towards the ruling classes as these forces tend to be?

How can artists from more disadvantaged backgrounds give their work the best chance of survival?

***

Cohen has been interested in the arts since her stage debut, at age two, as a rabbit in a local theatre production. In her early years, she tried dancing, the piano (“but my mother told me I was tone-deaf”), and painting. “The truth is, I wanted to be an artist. I wanted to be a painter. I thought, ‘If I learn to animate, I can paint.’ So I went to New York University to do animation. I thought they had animation classes. But they didn't.” A lack of animation classes wasn’t the only issue Cohen had to contend with. NYU was a lonely place to be in the late ’60s for a woman trying to figure out her creative path in a sea of men. On the surface, she had arrived at an aspirational location, for the school was scattered in stardust. Martin Scorsese taught classes and Oliver Stone was often around. These trappings belied the rampant misogyny which meant that Cohen was constantly second-guessed by the men in the film department. As she puts it: “The guys who ran the equipment all knew better than you did.”

Cohen’s driving force was not a particular career role, but the expression of ideas. So when her class was given an assignment to make a three-minute film about how to open a door, she was unimpressed. “I thought that was the stupidest assignment. Instead, I raised some money and made a film about Black Jews who were hiding in the pine barrens of New Jersey, who had escaped the anti-Semitism in the ghetto of Philadelphia. I thought, ‘Nobody's made a film about them. That's much more interesting than how to open a door.’” Due to the steamrolling nature of the men in the film department, this project was subject to interference. “One of the guys in the film department who handed out the film cameras said, ‘Let me come shoot it for you,’ and he was just horrible to work with. He took over and then most of the film was light-struck.”

This patronizing attitude was everywhere. Haig Manoogian (to whom Martin Scorsese dedicated Raging Bull) told her that women had no place as filmmakers and that she should probably leave school because “the best I could become was an editor, and the best grade I could get was a C.” Nonetheless, she kept plugging away. “I tried to take as much advantage of the situation to discover what it was that I wanted to do. I had to figure out why I was there. I knew that I wanted to make this film about my father because he was a bigger-than-life character. That was the way I reasoned being in film school.”

The film about her father became Joe and Maxi. It was released as a documentary feature in 1978, immediately stirring both praise and controversy and securing a cult prestige that causes it to crop up in repertory programmes to this day. Mainly shot on 16mm when Cohen was 23, eight months after her mother died from cancer, it’s framed narratively as a way to bond with her dad, Joe, after years of estrangement. Theirs had been an inappropriate relationship when she was an adolescent, involving sexual behaviour and beatings. She was scared, but she never stopped loving him. Joe and Maxi is a casually shocking chronicle of a dynamic that veers between touching and queasy. The vulnerability that Cohen would later inspire in her interviewees finds precedence in her own emotional nakedness before the camera's gaze. She is unafraid to show herself stunned into silence by the tsunami that is Joe.

Formal rather than filmic influences set the tone of the documentary. Cohen learnt her craft through working on magnetic media, where she says that editing meant literally cutting then scotch-taping film back together. To avoid too much of this, she developed a habit of shooting in long takes. “Years later I saw Faces. John Cassavetes could have influenced me but I hadn’t seen him at the time,” she says. When Joe and Maxi was released, documentaries tended to be contrived around a pose of objectivity. As Cohen recalls, “Somebody would be shooting and you would have a narrator explaining what you saw or interviewing someone. My favourite accolade for Joe and Maxi came when it was played in LA. Some guy came up to me and said, ‘Who played your father?’ It was so real, he thought it was fiction! The intimacy and this way of working was instinctive. When I made video, the camera was an extension of my hand and my mind. A lot of people have told me over the years that Joe and Maxi influenced them, filmmakers who are very well known and who are much more successful than I am. . . .I don't know if I should say this but Michael Moore once said that to me, and Judy Helfand and Michel Negroponte.”

***

Magnetic media marked a revolutionary departure from earlier television cameras, which were so heavy that vehicles had to transport them. In 1967, Sony released the Portapak, a two-piece set-up composed of a video camera connected to a tape recorder, both small and light enough for one person to carry around. It used magnetic tape, as did the later iterations that Cohen used: a one-inch open reel and 3/4-inch U-matic. (Although by 1994, she had upgraded to digital. Birty: Godmother of Watts and South Central Los Angeles: Inside Voices were shot on D2, a digital video camera.)

While Cohen was finding her filmmaking legs, so too were people from different subcultures. The freedom that magnetic video offered to shoot one’s community away from establishment red tape and systemic homophobia made it a form that appealed to collectives like Queer Blue Light, a non-profit organization that operated from 1971 to 1974 capturing vignettes of gay life in San Francisco. “You weren't going to be able to get a studio television camera that weighs 400 pounds and commercial people weren't going to be interested in your subculture,” says J. Vincent Raines, who spent the years between 2000 and 2008 volunteering for the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, a museum and archive of materials and knowledge promoting understanding of LGBTQ+ history, arts, and culture. He says that magnetic media opened up possibilities for his community. “It was more accessible. In many cases, it was cheaper; it was reusable; it didn't need to be sent away to someone else to process. So if you were dealing with material that was sensitive in some way, you didn't have to involve a third party. It was more easily shared, it was more easily and cheaply duplicated than, say, a film.”

Over eight years, Raines digitized thousands of hours of audio and video from the GLBT Historical Society’s archive of film and magnetic media. “This was all material that was sitting in boxes on a shelf somewhere for decades,” he tells me. “I found it fascinating to bring this material back to life. A doorstop-looking reel of tape could have images and sounds and bring you back to another time to meet people who, in many cases, are long gone.” His descriptions of the works channel the energy of the ’70s gay counterculture. Raines digitized videos by Queer Blue Light shot on EAIJ-1, a one-inch open-reel videotape that came out in 1969. “They ran around the Castro District in San Francisco taping various events, including the second or third Castro Street Fair in 1976. Harvey Milk pops up in one spot.” Then there are more personal scenes. “Not only were they out on the street, there were a few tapes where they're just goofing around sitting in someone's living room, so there's insight into more of the interior lives.”

The biggest collection he worked on was shot on U-matic, “you know, the chunky three-quarter-inch videotapes,” by a man with a home-video business who recorded everything from leather and drag pageants—Mr. Leather and Miss Continental—in his native Chicago, to fundraisers and talent shows in San Francisco. “That was just an enormous collection,” says Raines. “What was poignant is that, towards the end of it, there were tapes made by his partner after he had died of HIV. A lot of the challenge working with that archive is much of the material came in a chaotic fashion and out of order as people died during that plague [the AIDS epidemic]. Often the family, or whoever was trying to get rid of a lot of property, would just throw them in boxes and donate them.”

All the work that Raines digitized remains held at the GLBT Historical Society archive, and some, like “The Gay Life,” a radio show made on audiotapes, is publicly available to listen to online.

The counterculture of the late ’60s and ’70s existed along identity lines, but also, notably, along anti-establishment lines. We need only hark back to images of Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider, grinning under a walrus moustache as he rides a motorbike through the desert to the sound of Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild,” to know the type.

Michael Shamberg has been a Hollywood producer since 1980 with big-boy credits like Pulp Fiction, Erin Brockovich, and Contagion to his name. In another era, he was a part of the New York video counterculture, and in 1970 co-founded the Raindance Corporation, an “alternative culture thinktank,” with Frank Gillette (a social activist and video artist), Paul Ryan (a former research assistant to Marshall McLuhan), Louis Jaffe (a musician and journalist with money to invest), and Marco Vassi (Gillette’s friend who went on to become a renowned erotic novelist). A journalist by trade, Shamberg met Gillette while covering a video art show and, after spending some time hanging out with artists, realized the potential of video art and public-access television. Switched on by a medium he felt had the potential to be a great social equalizer, he quit his staff job at Time Life. “I was young and didn't need much money and just felt it was a valid form of expression.” Raindance put out a video art journal called Radical Software that brought Shamberg into contact with an ever-greater network of video artists.

For Shamberg, the most compelling element of magnetic media was rooted in his journalistic impulse to document events freely. In 1972 he co-founded TVTV, a video collective that made documentaries using guerilla techniques, with Allen Rucker, Tom Weinberg, Hudson Marquez, and Megan Williams. “The first things we did were the political conventions in 1972. I have to laugh because myself and my partner, Allen Rucker, we'd go to the White House every day with long hair and press credentials.” Shamberg was filming in Steven Spielberg's office when he didn't get nominated for Jaws, and the extremely charming response can be found on YouTube. He says this was a time when even well-known directors were less guarded. “There were no publicists to say, ‘No.’ Everything you got was much more authentic. Whereas now, people are both guarded and filtered or, conversely, with social media they're simply doing it for the camera.”

An ex-boyfriend introduced Cohen to magnetic video and it immediately impressed her as free from the hierarchies and misogyny of traditional filmmaking. She went on to do a master’s at NYU where she became friends with other video artists fuelled by the same ideals as Shamberg and his collective. “We were guerrilla TV-makers, all seeing video as a political tool. We could play and go anywhere and experiment. It was the beginning, so nobody knew more than anybody else. There was a level of equality between men and women and there was a kind of freedom about it.”

***

As video artists were finding their way forward, a new era of public-access television was dawning in America. Previously, there had been only three television networks: CBS, NBC, and Public Television. In 1969, the government mandated that two channels be given to the general public to create their own programming. Public-access television decentralized the means of production and freed broadcasters from having to abide by studio production values, tone, and equipment. Both Cohen and Shamberg say this foreshadowed how smartphones and social media have blown open citizen journalism today.

The truth of this parallel is evidenced by the extraordinary social impact of Darnella Frazier, who had the presence of mind and fortitude to record on her phone the brutal murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police officer Derek Chauvin, which sparked an explosion of Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 and led to Chauvin’s eventual conviction and sentencing. Indeed, filming on smartphones has become a ubiquitous way for non-white Americans to document the racism they experience and witness, making it harder for wider society to turn a blind eye and, sometimes, mobilizing real change.

Back in the early ’70s, Shamberg’s work with the Raindance Corporation in documentary videos overlapped with public-access television to the point that he wrote a book, Guerrilla Television, in 1971, solidifying the values central to both mediums. “I look back on it now and it was so jargony it's a little bit embarrassing, [but] it was a manifesto about democratizing television. The idea of a manifesto is that for a new media or art form, historically, like with Dadaism, somebody is always going to write about it. So I'm proud of it as a manifesto. It summed up a lot of ideas.” In Guerilla Television, Shamberg writes, “The inherent potential of information technology can restore democracy in America if people will become skilled with information tools.” Like Cohen, he was influenced by the idea of new technology for social change, a movement spearheaded in America by Red Burns and George C. Stoney, the latter carrying the epithet “the father of public-access television.” Cohen recalls speaking alongside Shamberg on a ’70s panel about programming hosted by the National Cable Television Association. “When I started out in video, there were a handful of people across the country and we all knew each other. The people who were part of TVTV are like my closest friends,” she says, citing projects with TVTV participants Nancy Cain, Skip Blumberg, Elan Soltes, and Wendy Appel, who co-produced Cohen’s South Central Los Angeles: Inside Voices.

Fresh from graduating with her master’s in 1971, Cohen instantly found work creating public-access television in Cape May, a small town in New Jersey with a population of 5,000. Her local community series was called Are You There? “I showed up and taught people in town how to make television. I had an open workshop. I did a TV show once a week and played the videotapes that the public made. I said, ‘Well, if you want to respond, just call me up and I'll come make a video with you.’” The impact of Cohen’s work in Cape May was historical, causing her to butt heads with the town’s mayor. “A dialogue happened in this town and as a result, for the first time in 100 years, a Democratic mayor got elected. [Public-access television] changed the social, economic, and cultural trajectory of that town forever.”

After a year in Cape May, Cohen returned to New York where she worked as director of the Video Access Center, part of the Alternate Media Centre (AMC). This was the first public-access facility in the United States, set up by Red Burns and George C. Stoney. The AMC trained thousands of laypeople in the tools of video production. After another year, Cohen set up video arts distribution at Electronic Arts Intermix, putting out work by the likes of Tony Oursler and Bill Viola, “all the people who were using video as art.” Oursler and Viola were pioneering multimedia artists at the time and have gone on to have prolific, award-winning careers, exhibiting work to this day.

Cohen recounts AMC alumni recording everything from homophobic police officers talking to members of the gay community to Salvador Dali just kicking back; from Betty Dodson’s masturbation workshops to Allen Ginsberg in his tiny apartment in the East Village; from the 1974 Democratic Convention to Yoko Ono talking cosmic feminism in her white room at The Dakota. Cohen wore many hats in these scenarios, enabling others to make work, but also shooting her own stuff. It was a time when the fruitfulness and momentum of making videos far outweighed thoughts of storage and archiving.

***

In 2019, Matthew Hoffman, a young Canadian studying for a master’s at NYU in Moving Image Archive and Preservation, was doing a collection management assignment that involved a variety of possible tasks, some purely organizational, some involving collaborations with artists. “We were essentially given a long list of people we could request to work with in a top-three order. I looked into Maxi's work and started reading about Joe and Maxi; it sounded like everything I've ever wanted to see in a documentary film. I watched it and thought that it was one of the best documentaries of that era, as important as anything the Maysles (Grey Gardens, Gimme Shelter) were doing in the ’70s. I was shocked by how raw it was.”

Hoffman was moved. “When I came to class, I said, ‘Look everybody, I have never gotten my first choice for anything over the last year and a half, and you all know that, so I want to do the Maxi Cohen collection. Does anyone have issues with that?’ Everyone said ‘No’ and then I turned to the professor and said, ‘Okay, so that's what we're going to do.’ I was very adamant.”

Over the course of the collection management assignment, Hoffman spent quality time at Cohen’s studio in SoHo, New York going over records of her archives. He was excited to see that she still owned the master materials of films shot on magnetic video. “It leaves this great window open for preservation that's timely.” He created a list of Cohen’s video works, noting which had yet to be preserved, considering both the films and the surviving recordings from Cape May and the AMC.

The non-film works felt too sprawling for a student project. “It was expansive and I don't know if I was ready for that quite yet.” There was much to choose from, which “speaks to the fact that there's so much to preserve with Maxi and with so many artists. If only those resources were readily available because it is not only a financial commitment but a time commitment. It's amazing how much there is to be done.” Hoffman’s anxieties about the scarcity of preservation resources were born out in the experience of Raines. He relays an illustrative experience with buying and selling a time-base corrector that he first bought on eBay for a little more than $100 and then auctioned off a few years later. “I put it up with a really low opening price and it sold for almost $800. So, obviously, in that amount of time, they had become scarcer and grew in demand.”

For his thesis project, Hoffman decided to digitize eight films—one feature, South Central Los Angeles: Inside Voices, and seven shorts: Second Grade Dreams, Intimate Interviews: Sex in Less Than Two Minutes, Las Vegas: Last Oasis in America, Birty: Godmother of Watts, Boney, The Edge of Life, and How Much Is Really True? He hired a vendor (Mercer Media in Long Island) based on affordability and the ability to meet the required technical specifications; he also observed and assisted in the digitization process. When the video files were delivered, Hoffman performed quality control and, once satisfied, ensured that both the newly digitized works and the magnetic media masters were stored according to best practice.

“How lucky can I be?” was Cohen’s reaction.

For several years, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York had shown interest in paying for a 4K restoration of Joe and Maxi. Hoffman and Cohen seized the idea of using the restoration as a hook for a retrospective featuring her newly digitized films. Hoffman collected the digitized files on March 9, 2020. The World Health Organization (WHO) announced a global pandemic on March 11.

When Cohen and I first talked in August 2020, well into the COVID-19 pandemic, MoMA had gone quiet. “Communication has only gone in one direction. Whatever plan was in place may no longer be in place,” said Cohen, deluged with other projects but keeping a half-hopeful, half-mournful eye on the horizon.

So, then what?

***

Legacy is a crushingly heavy idea that requires all logistical dominoes to be in a row. Without the Raineses and Hoffmans of this world, less mainstream and more obscure work would be as good as extinct.

But what about the people who do not have access to the means of production in the first place? Even though magnetic media was more accessible than other forms, its heyday wasn’t a lost Eden powered by equal opportunity. “Let's face it, even back in the ’70s and ’80s, getting this equipment for most people required at least a certain income, unless someone was fortunate [enough] to get it through school or a friend,” says Raines. “Much of the material we have from the ’70s and ’80s is by men, and white men in particular, so it didn't completely open the door to everybody. There are a lot of barriers to having your expression preserved and your legacy carried forward, especially in this realm where you don't have a studio and a machine and a patriarchy behind you.” Still, without the patriarchy behind her, Cohen managed to make the work, but its preservation was down to Lady Luck visiting in the form of Hoffman’s university assignment. This is not a lottery that many disenfranchised creators tend to win.

Shamberg agrees with Raines that the video art scene, as he knew it, did not include the widest demographics. Having used the term “marginalized” to explain how his peers in the counterculture identified, he is keen to stress that it had a different meaning then. “We were a bunch of, basically, white people wanting to express ourselves about the culture. We were hardly oppressed the same way that women, Black people, and minorities are.” He is turned on by the possibilities of the present moment and doesn’t seem remotely nostalgic. “The rebellions that are happening now for political and media power have much more scale and weight to them than what we did. We were probably ahead of our times in seizing the means of production, but the dynamic of technological exploration continues to today.”

Shamberg has made his peace with not having a legacy: “I don't think you can look at me like some really good Black filmmaker [such as] Ava DuVernay, or [someone like] Quentin Tarantino, and say, ‘Well, there's a Michael Shamberg legacy.’ The abilities and skills brought to mounting those films are probably worthy of recognition, but not me personally.” Instead, his focus is on keeping on moving. “I’m 77 and I’m just going to keep working as long as I can, looking for what's new.” It’s perhaps easier to shrug off the idea of legacy when your works remain accessible. Shamberg doffs his cap to Pacific Film Archives, who have taken his TVTV collective’s archive into storage. Meanwhile, there are artists whose work disappeared before anyone even knew to save it. There will always be talented people who are locked out of the dominant technological platforms, who have not been brought up to believe that their voices have value. In such conditions—lacking access to technology and a support network—many also lack the confidence to push their work forward publicly and end up destroying it, either actively or through atrophy. As Raines says, “That happens so frequently with artists. It was so easy to do in haste with magnetic media, to just record over it or erase it, whereas, if you've made a film, you have to go to the trouble of burning it. People don't understand the value of what they have in the moment.”

A normal way of working on video involved recording new footage over existing tapes, meaning that a lot of Cohen’s material from the AMC years has been lost. Raines talks about the same phenomenon with regard to the Queer Blue Light collective: “At some point, one of the guys reused tapes to record Chinese lessons, probably for pay, and recorded over who knows what. I heard that they had a whole tape of Harvey Milk practising political or campaign speeches and I'm pretty sure they recorded over it. So that's the peril of magnetic media. What's priceless in the future, you don't know; you might record over it.”

As towering Australian goddess Nicole Kidman said on the Marc Marron podcast WTF, “I give blood and then the interesting thing is to see the reaction.” Artists offer something that makes them vulnerable—and subject to a private backlash of self-questioning and doubt. Perhaps a way to reduce instances of work being lost is to prioritize artistic communities over individual stardom and teach creators that they are not best placed to judge their own work. If all creators had a network of cheerleaders, maybe some wouldn’t have their chance of a legacy strangled at birth. The problem, as ’twas ever thus, is that potential profitability is mistaken for intrinsic value. No matter how many cautionary tales exist of great artists like Vincent van Gogh and Emily Dickinson, who laboured in obscurity for their lifetimes only to gain an enduring legacy after death, the comfort of being recognized by a large number of people—and their wallets—in the here and now fogs up a more existential awareness that this moment will be washed away by future ones and no one knows what works will be left standing.

There is, of course, the real and pressing need that we all have to survive by selling our skills. While the industrial fight for fair pay will never end as long as bad-faith operators, per Oscar Wilde’s definition of “knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing,” wield exploitative pay practices, it is vital that artists resist this kind of cynicism on an individual level. Most creative people, understandably, want to earn a living from monetizing their art, yet struggling to do so does not invalidate the art or preclude its potential for finding an audience at a later date.

***

How important is it that a work lives in public? Does it still have value if it doesn’t connect with a large audience, or has no audience at all? Some idealists believe in art for art’s sake. That is to say, something profound happens in private when you work on your art. I think about the day I spent as a volunteer art critic for The Koestler Trust, reading a binder of poems by prisoners identified only by their serial numbers. These poems reckoned with primal emotions and experiences: love, death, suffering. They would never bring their authors fame or fortune, or even recognition, yet by putting words to their feelings, something important had already happened in their lives. But for many artists, creation stems from wanting to communicate something to leave behind. For that possibility to exist, the work must exist. Dead formats tell no tales.

***

Since the pandemic hit, Cohen has worked alone out of her studio in SoHo on a variety of projects, without her usual producer, assistant, and interns. There is a book, a film she’s been gathering material on for 40 years (“a sequel to Joe and Maxi”), a feature documentary on ayahuasca, a feature documentary that arose from her filming evicted artists in her SoHo neighbourhood breaking into a fancy hotel, and an art installation on “the movement in water,” created in connection with the Buckminster Fuller Institute’s Design Science Studio who gave her an award in service of imagining a world that works for everyone. “It’s really exciting because you’re working with a lot of futurists and people who are highly optimistic. You see the renaissance—or the regenaissance—below the surface of all this turmoil, and all this male, right-wing domination, trying to play itself out.”

When we speak again a few months later, in January 2021, it’s all systems go, and she is thriving. “I have a film editor who’s edited all of Gus Van Sant’s films. I’m in a cyber community.” What’s more, to the delight of Hoffman, who is only hearing this news on our call, MoMA has come through with the digital restoration. “Seeing Joe and Maxi made me really want to put on this epilogue,” says Cohen, referring to the eight films digitized by Hoffman.

Seven Women, Seven Sins is the other of her films out in the world, anchoring her in the consciousness of certain industry gatekeepers. She tells herself to make a note to reach out to the curators in Italy and Belgium who wanted to host retrospectives after Chantal Akerman died and before her newly digitized canon existed. On our first call, reference had also been made to a streaming platform interested in buying South Central Los Angeles: Inside Voices, as its subject spoke to the Black Lives Matter movement. “I never heard from them actually,” says Cohen. “I don't know if I stayed on them enough. I should really pursue them. I'll make a note. I have, like, lists and lists of things I have to do.” Papers rustle over the line. I say that maybe she has enough on the go, but no. “It would be nice for the film to have a home.”

Finding homes for all the newly digitized works is a Sisyphean task, add to this the fact that there is so much work yet to be digitized from Cohen’s time in Cape May and at the AMC. Much has been lost or recorded over, but stray treasures abound, even as their ripeness for preservation is risked with every passing day. Cohen has held onto the Yoko Ono video from her AMC days, which Hoffman finds thrilling. “I'm ready to get the Yoko Ono transferred right now!”

Does she feel like she gets enough credit for the trailblazing work she did? “Well, that's so sweet that you're writing and that Matt is doing this because the truth is that I've never really been out there. I don't brag, I'm a modest person, but in having these discussions I see that I did make a real imprint on the cultures. So I appreciate all of this. None of us want to go and be forgotten.”