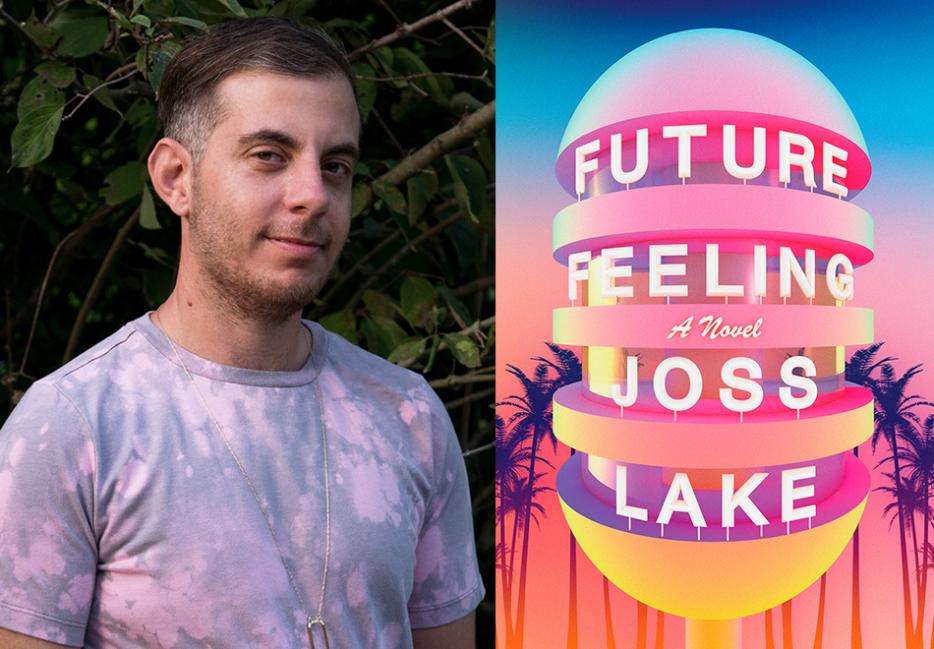

Future Feeling (Soft Skull Press), Joss Lake’s debut novel, is a delightfully queer book. Penfield R. Henderson, the novel’s narrator, is a trans man living in a near-future Brooklyn in which social media is still a powerful force but also cellphones have hologram capability and New York City’s subway cars scan their passengers’ cumulative emotional state and change colors accordingly, like a public mood ring. Pen is in a lull in his life at the start of the narrative: he’s a dog-walker for those wealthier than him, he’s got a casual sex thing going on with a minor celebrity, and he has a love-hate parasocial relationship with Aiden, a trans social media influencer with perfect pecs and a seemingly serene soul. When the hate part of the love-hate gets a bit too overwhelming, Pen enlists his roommates—one a witch, the other a hacker—and attempts to hex Aiden.

Instead, the hex ends up affecting a total stranger, Blithe, a transracially adopted trans man in California, who plummets into a sudden, deep depression. In this near-future world, queers in distress aren’t left to their own devices; they’re assisted, in more or less direct ways, by a kind of queer caretaking body, the Rhiz (pronounced like the word rise), whose name gestures at “mycorrhiza,” the mutual symbiotic relationship between fungi and plants—a kind of mutual aid, if you will. The Rhiz sees fit to direct Pen and Aiden to figure out, together, how to help Blithe.

But this is, as I said, a very queer book, and these characters’ trajectories aren’t particularly linear or predictable, making Future Feeling all the more fun to read as its surprises, anxieties, and hilarities unfold alongside each other unexpectedly.

I spoke to Joss Lake over Zoom about the novel’s structure, world, and incredible narrative voice. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Ilana Masad: About halfway through the novel I realized that even though Pen, our narrator, is in his early thirties, he narrative is a kind of coming of age. In fact, that’s the case for all three of the trans men whose lives Future Feeling focuses on. What interested you about this post-transition, post-coming out time in Pen, Aiden and Blithe’s lives?

Joss Lake: I think what interested me was the way that Pen had transitioned but was still in this very teenage, angsty mindset. And I was interested in this queer non-linearity of life phases. He's at a point in time where maybe some of his cis “well-adjusted” friends are having children or moving up in their careers, but he's sort of moving through puberty and then getting to a point where he's like, What is it that I actually want? [I was] playing around with disrupting these developmental milestones, with [the question of], like, what does help people move through these stages? How do you hold yourself together when maybe you're doing things out of order? Maybe you know, intellectually, that you can do something at any age, but emotionally it feels very much like, Oh, I'm stuck, I'm behind, but also I'm just getting a chance to do X, Y, and Z.

For Blithe—because of the hex, but potentially this could have happened anyway—he’s just starting to confront all of this emotional turmoil and trauma for the first time. So his career was in a good place, but he’s now sort of stepping off onto another path. And then we have Aiden who is coming to terms with the limitations of his role as an influencer and is trying to conform to some social messaging and find some sense of security.

One of your blurbers, Jordy Rosenberg, wrote that this book “accomplishes that rare and difficult goal: the conversion of anxiety into laughter.” Your narrator, Pen, is an extremely anxious person. He’s not always likeable—although he’s often extremely relatable, TBH—and he messes up plenty. But he’s also hilarious, and he’s able to poke fun at himself and his anxiety. How did you develop Pen’s beautifully unique voice?

It was a long process, and originally, in earlier drafts, I didn't necessarily know that he would evolve [as a character]. I'd taken this class in grad school on the hysterical male and I kind of hated most of what we read. It felt like you're sort of trapped inside these very fragile cis male narrators, and there's no movement—you're just supposed to either find humor in their fumbling around or identify with them if there's something about them that's relatable, but there's no particular movement. At first, I thought I could create a hysterical trans masculine narrator, and that would be subversive in itself. It was fun to do that, but I was like, This feels very limiting. And I don't think it's actually that subversive to have a white trans hysterical narrator just spinning off in his head. I don't know that I would really care to read that, after a certain point.

So I started to think, what if this narrator has all this fragility and this messy way of relating to people, and I also send him on a journey? I also wanted to have other characters give him feedback and elevate other voices; I didn't want people to be trapped in his consciousness. I wanted them to have all these ways of relating to other characters and other characters’ perspectives rubbing up against his so that he's not our elevated, picaresque hero. In some ways he is, but he has all these other elements and people that can balance him out.

There was this question of what does move someone out of deep angst and [out of] taking themselves too seriously when they are stuck in a dark place? One thing that very organically arose was humor. Because the more he dug into, like, my life is horrible, I live in this whatever apartment in Ridgewood and I just walk people's dogs, the more heavy it felt. So there was a lot of counterbalancing: I'm going to counterbalance this heavy angst with humor, I'm going to counterbalance zooming in too far on him with other people coming in to add some breathing room.

I think another factor was that I wrote a fairly serious, experimental, historical fiction novel, and then a memoir in the third person about transitioning, and it was very dark. I couldn't get them published. And then I started doing The Artist's Way [practice] where you write three pages every morning without thinking and what came out was basically Pen's narrative voice. I was sort of surprised that that was spinning around inside of me, but it was pragmatic to go with it. I wasn't thinking very intellectually about it—it was just some part of me that I hadn't really thought about or explored.

Would you tell me a bit about how you arrived at the concept of the Rhiz—this officialization of the unofficial queer underground network that anyone who's queer has (hopefully) had some kind of contact with?

It came out of a blend of personal experience and sort of imagining new possibilities. [In terms of] personal experience, just thinking about the interconnectedness of queer relationships, and using the internet in relating to queer folks, and the way you can find housing and all sorts of things just from knowing different people, and that being a kind of alternate structure—with its own problems—to capitalist, hierarchical ways of maneuvering.

The Rhiz also came out of trying to come to terms with the internet and feeling, myself, very depleted by the internet and social media, but also wanting to approach it neutrally. The internet can obviously have really negative effects and can also have positive effects, so [I was] thinking about it more generatively as a structure that is linking things together and imagining an underground structure that is parallel to the internet and is very relational. Because [the book] is set in the near future, and there are a lot of futuristic technological factors, I wanted—and I didn't have a ton of space to do this—but I wanted to gesture at the queer past, so that it wasn't like these characters are existing in a vacuum. I did want there to be a sense—or at least a way to mark—that generations of queer folks have been working together for various forms of liberation. I also wanted to build in a sense of vastness, so it wasn't like Pen’s life or Blithe’s or Aiden’s is the end all, be all of queer existence.

I did have a lot of fun building out the Rhiz. At first I wanted it to be a little more nefarious, like maybe there’s something sinister about it. But in a way it felt more subversive to have elements of a sort of utopia, because, to me, it's very easy to imagine a dystopia.

The world that the book is set in is just far enough in the future to include some technology we don't have, but it's near enough that it's very recognizably our own late-stage capitalism, social media influencer, climate disaster-filled world. So I was wondering what did setting the book a bit in the future allow you to achieve? Did it feel hopeful or bleakly realistic to preserve many of our contemporary social anxieties and ruptures in this future space?

I think putting it in the future helped me get a little imaginative distance. Setting it in the present, I would have felt more of a pressure to make things more recognizable. I mean, obviously you could set something in the present and still have these imaginative flourishes, but setting it in the near future just felt more spacious. It also gave me space to write towards something. In my immediate present, as a person and as a writer, things just felt very stuck. And so I think the future—not even in terms of following our present socio-political reality a little bit further, but the future in a more expansive way—allowed me to be able to move around in some possibilities.

I think originally, the idea was that by setting them in the future, I can take all these aspects of the present and turn up the volume on them so that the characters feel extra tense and squashed by these mediating elements, and then as I was writing and changing internally, it felt like I had some agency over determining what the future could be. So, again, not thinking in the way that we're receiving information from the media about what the future will be in ten years, but just as a writer—maybe I can decide in this narrative space what a future could be. Maybe the characters—in relation with each other, in relation to the Rhiz—maybe there is a way that they can evolve in some sense.

I did think a lot about how to modulate this so it's not a sort of uncomplicated happy ending. I was sort of afraid that by making any gesture toward things not being hopeless, that people would just scoff at it, like, Oh, that’s so naïve, who gives their characters a happy ending? Your characters should remain unlikable and suffer until the end. But who does that literature serve?

I want to talk about the structure of the book a little bit. It has a kind of prologue, and then three parts or chapters, and then we catch up to where the prologue left off. It also has these stories-within-the-story sections, where Pen is telling a story or putting together other people’s stories. Events bleed into one another at times, and the narrative focus allows itself to shift around. In other words, the structure of the book itself feels very queer to me, very much eschewing the familiarity of simple linearity. How did the structure of the book develop and what was your vision for what it would feel like to read?

I really wanted the prologue to be a kind of flash forward. The way that Pen opens [the novel], with the hex and his frame of mine—I wanted the reader to be cued that he wasn’t going to remain the same from the beginning to the end. I was sort of afraid that opening with him hexing [Aiden] would signal that maybe the book is very much about social media, which to me was the starting point, but then I wasn’t particularly interested in delving too far into that. So I wanted to mark the complexity and the layers by having this sort of signpost at the beginning—we’re building up to something and this character and the plot of the novel is going to change a lot from the beginning to the end.

In terms of the narrative structures—one generative way I was thinking about social media and the Rhiz is like: Okay, if social media companies have so much data about people, then in this sort of tilted world [of the novel], maybe there's a way that characters could use all the data to understand each other and to put together these narrative packages. How can we take surveillance culture and reshape it so that characters are taking on the role of writers? Part of Pen’s process of evolving is working through stories: the stories he tells about himself, the way that he's encountering other people's stories, the way he's relating to Aiden and what that's telling him about himself. So I definitely wanted room for there to be narrative play.

Having written this more experimental historical fiction novel and this memoir, I really was thinking more about the reader and wanting them to feel like they're in this heightened or different or exaggerated world, but there's a layer of generosity in the humor and how characters are relating to each other. I wanted [the book] to be inviting, through color and language and things moving around. And I did want there to be a lot of narrative elements, not to overly complicate things, but just to keep shading in complexities.

One of the novel’s main themes, I’d say, is the ways in which people—all people, mostly likely—project narratives onto people. This happens with the parasocial relationship Pen has with Aiden and the way he first gets to know Blithe through his data. But even as Pen learns more about who these people actually are (as opposed to his stories about them), there’s a sense that he can only go so far into their experiences. How did you decide how far to go into the various other characters’ stories and experiences, and what held you back from exploring some of them further?

It was a really interesting tension for me, knowing that I didn't want to completely keep us close to Pen and also wanting to model not going too far into someone else's experience—which is not a hard and fast rule, but it felt, at the time, like an ethical decision to stay in Pen and gesture at the complexity of other people's lived experiences without trying to narrate them too far. Especially, I think, with Blithe, giving him in dialogue and plot a lot of room to be taking his own space—going off and looking at his past and his ties to the culture of his family of origin—without me narrating that too closely.

So [I was] trying to gesture at Pen's own limitations, because he can access other people’s experience in some ways, but there's also this gulf. I think he's anxious enough that he would love to just find a way to close the gulf; in some fantasy, there'd be no tension if he could just understand everything and wouldn't have to deal with the messiness of other people's experiences. But I wanted to show that there are some things that Blithe has to do internally, or with people who are not Pen, that Pen just doesn't have access to. And that's just how I imagined a sort of ethics of having Pen work through different people's experiences and how he relates to them.

My last question, fittingly, has to do with resolution. At one point in the book, Pen spends time reading crime novels because he “longed for every loose end of a story to get tied up.” (216) There are narrative threads that are resolved in this book, and there are threads that are clearly deliberately not. How do you feel, as a writer and a reader, about leaving loose ends of a story dangling and free?

Maybe it’s just my TV watching habits but I do love these really tight structures, like in procedural crime shows where there’s a problem and then things happen and then it's tied up at the end. But in my actual writing and my way of experiencing reality, I wanted to have so many threads unspooling in the book that it would feel sort of artificial to have to neatly tie them up. So instead of looking at the end as Okay, how do I resolve everything that I opened up in the earlier sections, it was more like where can the characters end up that represents a new phase for them? Maybe in the new phase they don't necessarily get to wrap up all these other elements of their life. I wanted it to feel like they were continuing on in literary reality and that the place where the reader left them at the end was just starting the next part of their lives.