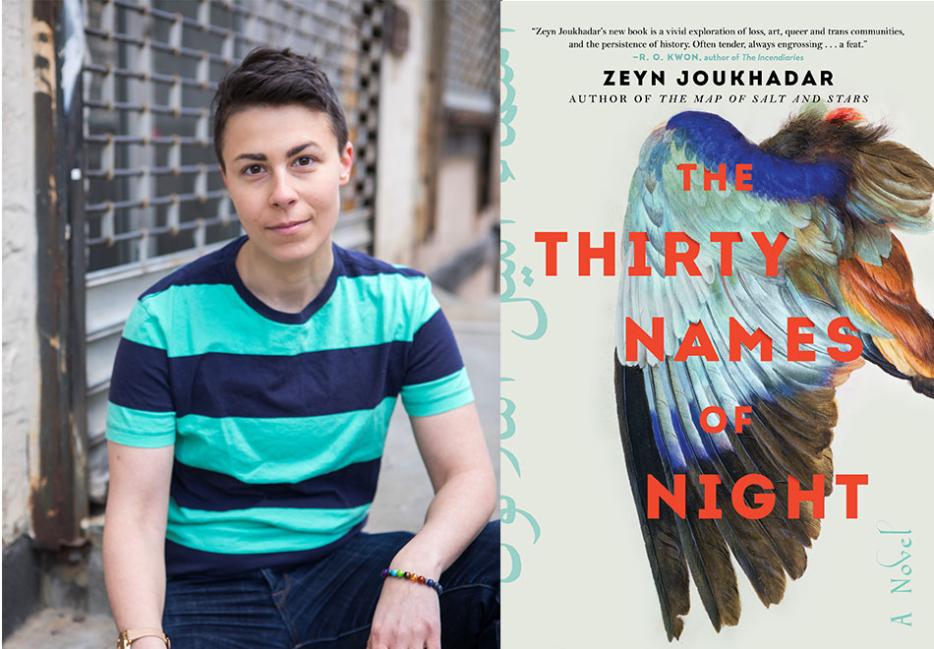

When I first start reading Zeyn Joukhadar’s latest novel, The Thirty Names of Night (Atria Books), I’m in the process of choosing my own name. One year or so into gender transition, the need to shed my given name is evident. I spend the summer combing lists on websites meant for expectant parents, searching for something to call myself that doesn’t make me feel like a fraud. By the time I reach Joukhadar in Italy over Skype to discuss his novel, I have chosen the very name that appears at the top of this interview. It means “light.” It’s aspirational.

Joukhadar’s protagonist is also searching for a new name. In The Thirty Names of Night, a young Syrian American man struggles to come to terms with his own transness as he cares for his ailing grandmother. All the while, he grapples with the grief he still feels over the sudden death of his mother five years prior. In order to imagine the life he wants, he must first understand the lives his ancestors lived. When he accidentally discovers the journal of a Syrian American artist named Laila Z, he begins to unravel the histories of queer and trans members of his community that few realized existed.

The Thirty Names of Night is saturated: in colour, in sound, in history, in emotion. Joukhadar captures the lives of several generations of Syrian diaspora, layering their stories on top of another—a palimpsest.

“I wanted to tell a story that was fundamentally about many things at once,” Joukhadar says. “It was just as much about being trans as it was being the child of an immigrant, about being Muslim, about being Arab American. I want those things to be inextricable from each other.”

Ziya Jones: I recently read an essay of yours where you mentioned that, when you first started writing the book, you wrote your protagonist as a cisgender, straight woman. What made you decide to switch directions?

Zeyn Joukhadar: When I was working on my first draft, writing a trans character wasn’t something I felt I could do. There was a sense of fear because I was still figuring out how I felt about my own gender. It wasn’t until I was working on my third and fourth drafts that I started to come out myself.

There was a funny moment in a writer’s workshop where another participant said, “There’s a lot of stuff in the text about gender but I’m not sure that it’s being fully unpacked.” I felt really seen. I started to think, if people are picking up on that subtext, I might as well write what I want to write more explicitly. As I played with gender as a theme in the text, I was navigating my own coming out. A lot of the work I had to do on the text was also internal work I had to do on myself.

That’s a lot of pressure! What was it like to write about someone who is coming out at the same time you’re trying to come out yourself?

In a way it was freeing, because even though the protagonist isn’t me, and the things he goes through bear little resemblance to my actual life, I was able to relate to him, to the yearning for liberation he felt. I wouldn’t have chosen for it to happen like this—I would have preferred to figure out my own stuff and then get back to the text when I was feeling more clarity. But so often that’s not how it works as writers.

I really appreciated that the protagonist remains nameless until he names himself. Kind of the trans dream. Why did you decide not to include his deadname?

As I was working through my drafts, I felt a sense of pressure to reveal or to hint at the protagonist’s deadname. I knew that cis readers were bound to be curious about it. But that kind of information isn’t useful for trans readers. That kind of reveal is really cis-centric. I wanted Nadir to be a character who had the agency to disclose, or not disclose, information about his life pre-transition.

So much of this novel is about who gets to tell an individual’s stories and what information about our lives becomes public. We mourn the lack of history we have on our queer and trans ancestors. But at the same time, one of the only forms of power they had over the way they were perceived was the ability to keep certain parts of their lives private. Similarly, I wanted my character to be able to use erasure as a tool of his own liberation. He had the ability to disclose the information he wanted to disclose, and to keep the rest private.

While erasing the protagonist’s deadname gives him agency, revealing his chosen name has a similar effect. What’s the power of a name?

Seeing your name for the first time after you’ve changed it is a rush. It’s also scary. When I put in the paperwork for my name change, I felt terrified. I had always thought of names as a gift that someone has to give you. Our parents give us names and, for me, there was a sense of guilt almost about changing that, as though I were giving the gift back. That prompted me to question why my parents had given me that specific name in the first place.

I began to think of names as more of a wish a parent might have for their kid. In my case, I think it was a wish for assimilation and for an easier life for me than my father had had. But I had a different set of wishes for my life. I ended up choosing a name that reflected my grandmother’s and that helped me to take pride and power in my name. It still felt like a gift, just a different kind.

I recently changed my name and chose a gender-neutral name that you can pronounce in Arabic. My given name wasn’t an Arabic one. Talking to my mother, who is Lebanese-Canadian, about choosing an Arabic name prompted some really interesting conversations that I had complicated feelings about.

It’s so complicated. And it’s a process, I think. My attitude towards my name changes as I have more experiences with it. It gains associations and it gains nuance. That’s been one of the most fun parts about changing my name. Your name becomes something that you get to take on adventures with you, if you will.

During this whole pandemic mess my partner and I [had] a civil union here in Italy, where we have been living. Hearing the name that I chose for myself, my real name, in that ceremony and having my partner speak it . . . it was a feeling that I really can’t describe. A feeling of deep pride and being seen that I never had with my old name. It’s powerful to let people love you with a name that you chose for yourself. It’s a way of letting people know how to love you better. I don’t think I understood that until after I had already changed mine, but I think it’s really beautiful.

You tweeted about feeling frustrated that reviewers who ostensibly read your entire book still managed to misgender the characters in their writing about the text. Fiction allegedly makes us more empathetic and understanding. Do you see any limits to the genre as a form of education?

Increasingly I get the sense that the people who want to listen will listen, and those that don’t want to won’t. You can tell the most nuanced and complex story, but people will only really hear you if they’re ready. I did feel it was important, though, to write for the people who would understand. Throughout the book I tried to set aside all the ways of framing transness that cater to cis people. I wanted to write as though I were talking to another trans person. I think the end result was that sometimes cis readers won’t always understand what I’m talking about, especially in some of the ways I write about the body. I talk about desire and discomfort and dysphoria. I’m okay with that. That was a risk that I was willing to take in order to tell the story I wanted to tell.

That’s also why I refused to make coming out the central trauma of the book. So often queer trans people of colour are expected to put our life experiences as racialized people to the side when we’re talking about being queer, [or] trans. Sexuality and gender are supposed to become the sole focal points of our identity. But, I mean, that’s impossible.

Speaking as someone who is queer and trans and Arab, I think there’s a related expectation that coming out is somehow guaranteed to be traumatic by nature of our background. Of course, transphobia and homophobia exist in Arab communities but they’re certainly not inherent to Arab culture. How can we hold our own communities to account without undermining them?

Those kinds of questions are always in the back of my mind, whether I want them to be there or not. I do consider how the stories I’m telling might potentially be used against me or against people that I care about. Are readers going to respond to this with Islamophobia or with racism, not understanding the full context of the story I’m telling? It’s really difficult to escape. But, at some point, as a writer, I have to accept that, while I need to do my due diligence and think through what I’m writing, I can’t control how people will internalize the story.

I loved that the book resisted the narrative of shame. It’s a stereotype that Arab families are shaped and compelled by fear. But it’s one lots of us can darkly laugh at because it does reflect our lived experience. Nadir, though, gets to come out to his mom, and even his teta, without being shamed for who he is. I personally found it healing to see some of my anxieties reflected in a narrative where the outcome was a happy one.

I knew that I could have written a narrative where Nadir faced more rejection, and it would have been equally valid. But in some ways, that would have been the “expected” story. I’ve seen lots of representations of LGBTQ+ Arabs and Muslims and other people of colour experiencing rejection from their families of origin or from the world at large and struggling with that. I’ve experienced some of that myself, but I’ve also had my Muslim family members be supportive of me. Not to say other representations of support don’t exist elsewhere, but I saw creating another one as a gift. For myself, and for the reader by extension. I thought, why don’t I take this opportunity to also highlight the fact that sometimes coming out actually goes really well and people can be really awesome? You never know who your allies are going to be, and sometimes people will surprise you in the most wonderful ways.

A lot of queer narratives are built around the idea of breaking from our roots and starting new, freer lives as the “real us,” whatever that means. As your novel unfolds, though, the characters grow more and more closely connected with their pasts. How can connecting to our pasts be healing?

For one thing, I think it helps us to feel less alone. For Arab folks and other people of colour, there’s generational trauma in a lot of our families and our communities, but that also means we’re surrounded by elders who have survived a lot. They carry wisdom that comes from their survival, and sometimes we forget to emphasize that too. Knowing that there are other people who have gone through what you are living can, in and of itself, be really healing.

The past can be healing, but it can also be haunting. In the book, this plays out as a literal haunting: visits from a ghost. What are you haunted by?

One way to answer this is to say that when I think about the ghost in the book, I think about all of the people that I will never get to know. I’m haunted by separations. Separation from my ancestors through death. Separation from my loved ones because of COVID-19. Separated by severed contact, whether by my choice or someone else’s. Even when a person isn’t physically with you, sometimes you can feel their presence. Some of those hauntings are consensual hauntings, like when you want to keep someone’s memory alive. But if you want to have good memories, you also have to remember some things that trouble you. To have a relationship to the past, you have to have a relationship to the joyful parts as well as the difficult parts.

I had no idea that New York had a Little Syria before I picked up this novel. What kind of research did you do in order to write about the neighbourhood’s history?

I was born in Manhattan and grew up in New York and I had no idea that Little Syria existed either. After I had moved away, I learned it had been there this whole time, and I became obsessed. I was like, “Why wasn’t this part of the history of New York that I was taught?!” I started travelling to NYC to visit the neighbourhood over and over. That was before I started writing the book, and those trips became a big inspiration for the novel. I knew the story of Little Syria was one I wanted to tell.

At the time I was visiting a lot, there was a really awesome history exhibit about the neighbourhood. It was made up of all these maps and pictures and music. One of the recordings was of a group of people singing “America The Beautiful” in loosely translated Arabic. That recording gets mentioned in the book. The first time I heard it was like, wow, what kinds of experiences did these residents have trying to hold on to their roots while also contending with the pressure so many immigrants face to assimilate?

Despite being surrounded by so many other queer and trans characters, Nadir struggles to recognize and name his own transness in the book. Do you think we’ve found the adequate language to talk about transness?

That’s a good question . . . I wonder if we can ever really find adequate language to describe such a wide range of human experiences. I think within the book I was trying to find a way to talk about the fact that, at least in my experience, people’s experiences of transness are so unique. When you’re exploring your gender identity, you find yourself asking, “Am I trans the way this other person is trans?” And often you don’t know! Maybe there are infinite genders or gender expressions. In the book, I was looking to capture some of the things I had personally felt. I hadn’t seen my exact feelings reflected before, which obviously makes sense. We could have thousands of trans narratives, and they would probably all be at least somewhat different.

Not only are they infinite, they’re ever changing. I wish I had the language to talk about how questioning and exploring gender doesn’t end in some static place.

I wish that too! I can’t help you with that one. I wish that too.