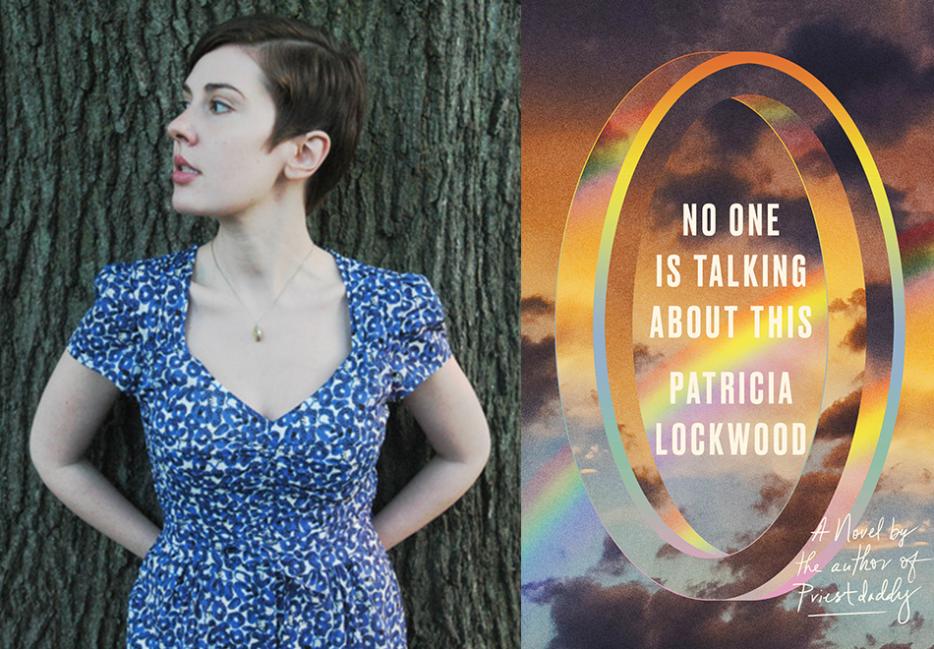

The narrator of Patricia Lockwood’s extraordinary novel No One Is Talking About This (Riverhead) spends a lot of time on the Internet. Most people do—early on, her podiatrist tells her about how much he loves to get on the Internet late at night and argue with people—but the narrator is powerfully, persistently online, a fully paid up member of the communal mind. Every morning, she lies and scrolls herself under “an avalanche of details, blissed, pictures of breakfasts in Patagonia, a girl applying her foundation with a hard-boiled egg, a shiba inu in Japan leaping from paw to paw to greet its owner.” Even when she is not actually hunched over a screen, she is online: carefully washing her legs in the shower after recently discovering that some people don’t do this, ordering the most disgusting food on the menu because that’s what the communal mind would eat for a joke.

Throughout the novel, the Internet in general and Twitter in particular is referred to as “the portal”—not because of a coyness about proper nouns, necessarily, but because the term more effectively communicates the narrator’s sense of the platform as a window she can sail through in order to enter the place where everyone is continually revising their assessment of reality, together, and where she has (for the first half of the novel at least) elected to live.

Lockwood is amazingly, hilariously good at evoking the experience of being capital-O Online—the immediacy of it, the contagion, its ability to render commonplace an idea that seemed irredeemably far out only minutes earlier, the way you routinely come across stuff that is so debilitatingly funny you almost feel scared, the way you end up taking part in a “stream-of-consciousness that is not entirely your own… one that you participate in, but that also acts upon you.” She is fascinated by the Internet’s effect on how we talk and therefore think; at one point, the narrator describes the portal as having “once been the place where you sounded like yourself. Gradually though, it had become the place where we sounded like each other, through some erosion of wind or water on a self not nearly as firm as stone.”

The narrator’s posts have made her famous, so that she has become a kind of spokesperson for the Internet: “She sat onstage next to men who were better known by their usernames and women who drew their eyebrows on so hard they looked insane, and tried to explain why it was objectively funnier to spell it ‘sneazing.’ This did not feel like real life, exactly, but nowadays what did?”

The question of exactly what real life feels like or exactly how it is supposed to go is examined with a sort of anthropological amusement in the first half of the novel. It takes on a different cast in the second half, when the narrator learns that her sister’s unborn baby has a rare genetic disorder. All that wild, untethered speculation about the experience of a life lived online and what it prepares us for suddenly finds a focus. The novel is very funny, and very sad, and I spoke to Lockwood about it last month.

Rosa Lyster: The first half of the book is this amazingly vivid account of the way things are on the Internet, what it’s like to be part of what you call “the communal mind.” There’s a part early on where the protagonist meets this guy she used to talk to a lot online. They’re having this conversation about how you’re supposed to write about the Internet, and the protagonist says, “everyone’s already getting it wrong.” So I wanted to start by asking you how you know when you’re getting something like that right?

Patricia Lockwood: I don't know that you ever do know. But with something like attempting to archive these really long movements that stretch back, they always stretch back farther than you know.

And I think the sense that you're not getting it right comes from the sense of many, many missing pieces of a lot of archival information. So that guy in particular was a person from the Something Awful board, if you want to get more specific about it. And Something Awful, and FYAD in particular, really exerted an undue amount of influence on the way people on the Internet talk now, and on the way the communal sense of humor operates on the Internet at the moment. But if you weren't there in that place, you’re missing huge, enormous chunks of information. So you can write about the endpoint, you can write about what it looks like now, but you think, Oh, I missed so much stuff. Like, I don't know who these people were, there’s all these in-jokes I don't know about, there were things that I adopted that I don't know their provenance.

What was interesting to me in this book was nailing down those pre-thoughts that sort of arise when you're floating through the Internet. These are not always my thoughts, but they were things that you could conceivably picture someone thinking, where you’re moving through the Internet, and you’re having sort of proto-thoughts that hadn't been formed into anything yet.

So when I can capture that feeling, then I know I'm getting something right at least, but in terms of like, have I captured the landscape here, have I nailed it all down, that's never going to happen. And you can think that you've done it, and then someone else can come along and be like, Alright, idiot, here's everything you've missed. I'm the guy who knows about this. You have these almost asocial people who have always had a curiosity about the darker corners of the Internet and just collecting what happens there. Those are the people who really know what's going on and the rest of us are kind of Johnny-Come-Lately where that's concerned, piggybacking on their research, or on the many, many long hours they blog.

The person who knows exactly where this thing comes from is a very strange person almost by definition, right? Potentially not the kind of person you want to be stuck in a lift with for too long.

Oh, I would LOVE to be stuck in a lift with that person, or just to spend all night just driving up and down the streets with them. It’s a sort of voracious, ephemeral appetite and curiosity, with no end. That is actually the sort of thing that I like—I want to be around the person who’s like, you know what, I’m just going to go down this wormhole for the sheer velocity of it, I’m going to jump down there like Alice in Wonderland just for the feeling of it. I like people that don't necessarily know why they're interested in something, why they're collecting information. We all have our own areas, when it comes to those things, but I think doing it on the Internet is a little bit more dangerous for your mind. A little bit of the poison does just get pumped in, and there’s really not a whole lot you can do about that.

And there are people with a higher tolerance for that sort of thing. You think about, like, the Facebook guys whose job is to look at the worst posts that anyone could ever conceive of—there are people out there with a slightly higher tolerance for that kind of thing.

But there was this idea, I think that for a very long time, that the Internet was not really worth writing about—that if you included something like IM chat transcripts, it was really outré, but also kind of like a fuck-you thing to do, like it was so ephemeral and so trivial that it didn't belong in books.

And I have something of that same sort of feeling myself at times, especially with new technology. And then you're just like, if I’m spending four hours a day on this thing, it’s not worth writing about? It's worth wasting my life over, but it's not worth writing about? What the fuck is that?

Why do you think people have felt that it isn’t worth writing about?

I think it's the McDonald's phenomenon. I had this when I was a kid—I was like, well, I can't say the word “McDonald's” in a poem, because then, you know, in 500 years, someone’s going to come along and read my poem, and they're not going to know what McDonald’s is. So it’s this exaggerated sense of your own longevity in the historical mind, is what I think it is.

You want to be writing something immortal, I think. A book is a serious thing, for a lot of people, whereas what we’re doing on the Internet, in our minds, is fucking around, right? Like, why would we enshrine this in actual print? But that idea started to seem really perverse to me. I don't know why it took us so long to incorporate the Internet in our work. This is how we're talking to people. We're not chatting with them on the phone, necessarily. We're texting them or emailing them. So why do we want to have it look different in our books? We think it's like Jane Austen is going to get mad.

It’s changing, I think, but your book is one of only a handful of novels I can think of that give this very realistic portrayal of social media and the Internet, from the perspective of someone who knows from whence she speaks.

Well, it just felt like it would be lost. And then I thought, you know, if I’m addicted to this medium—as clearly I am—what am I doing, I am pouring my life into it. Clearly every moment that I'm on it, I'm making hundreds of tiny proto-observations, and where are they going to go?

And the interesting thing about it is that in order to replicate that experience, you have to build a fake Internet in your book. And that is way harder to do than it seems, because the Internet is written by millions of people. And it's just you and your book, and you're the only one doing it. You're only as funny as one person, you're only as observant as one person, so it's going to be a lot harder.

If you make up a joke, and you make up some sort of craze that's sweeping the nation, it has to actually be something that would that would spread like wildfire that would capture the public imagination in some way. You’re taking the entire burden of communal thought on yourself. You have to be as fast, you have to be as funny—you have to build it the way it actually looks.

One way you could read the novel is that it’s expressing this wariness about what the Internet can do to the way one thinks. I don’t read it at all as a condemnation of the Internet and social media, but I can imagine people who are wholly freaked out about the potentially destructive properties of the Internet interpreting the novel in that way.

I think it’s a good point—that some people could definitely, with relish, present it as a book that is a sort of condemnation of the Internet and this sort of communal life. I don’t think that’s what it is, and I don't think that you think that that's what it is, but because I write satirically, and because I'm willing to look at the excesses of my own people and my own side, there's always a sort of dual purpose with that kind of observer, right? It can be taken and used by the wrong people.

But I think this is built into the book—you see at the end, where the character of the sister, talking about her ability to connect with other parents of children with the same disorder her daughter has, says, “Can you believe that we have this technology, that we're able to talk to each other about this.” The fact that you have these photographs, these videos, that you've been talking this way, with people all over the world, who also have the disorder that the child does, or have family with this disorder—that is why we built this thing, in order to be able to do that. This absolute physical transcendence where you’re just out of your body, you're up in the air meeting people—that is why we did it.

So yeah, I think you can make those observations in the first half. And you can also make observations about how the language gets really crunchy, and it doesn't feel like it's yours anymore. And there is a problem with that, of course. But then it comes to the second half of the novel; she is using that language to think about the child, she's using that language to cope with what's happening to her and what's happening to her family. So this is why we build these things. This is why we do this, because we can turn them to our use. They can elevate us, they can be our tools.

I was talking to my mum a while ago and I realised she knew what the Proud Boys are. A little part of me died, because what kind of world is it that my South African mother has to know that now. It made me think of a bit in your book where it says, “The amount of eavesdropping that was going on was enormous, and the implications not yet known.” When you think about the Internet now, do you have a clearer idea of what the implications are, or is that just a moving target?

My husband in this scenario is like your mom, right? For a long time, I'd be like, This is what’s going on with QAnon, you need to know what’s happening with QAnon because it’s going to be really important. And he would look at me, and he would just be like, I don't need to know about QAnon. Well, now he knows about QAnon, right?

So for the people who get to it first, we’re like, Why the fuck do I have to know about this? Why do I know about this thing? Why am I paying so much attention this? And there’s anger, almost, at the people who don't know about it yet. And then once they do know, there's another kind of anger where it's like, why did they ever have to learn about this thing in the first place? This should have been for the real Internet heads only. Our moms shouldn’t have to know about this, my husband should not have to know about this. But now they do.

Not knowing about it or paying attention to it doesn’t prevent these people from rising to ascendence. But at the same time, us knowing about it in every detail also does not prevent that. So we’re coming at it from the opposite side, where if we pay attention to every minute movement, maybe we can affect it in some way. Like, if I follow the thread of what is happening every single moment, surely that must affect it in some way—surely that means I have some say over what is happening. We don't, and neither do our moms and neither do our Jasons.

That sort of very recognisable impulse, where the protagonist thinks, If I just train a keen eye on this, if I just don't take my eye off it for a second, I will have some control over this situation. Where do you think it comes from? Is it unique to the Internet?

I don't think this is a new thing. I think it goes back all the way. At the beginning of the book, the protagonist is traveling to all these other places, and she’s always picking up the newspapers, because as long as she pays attention, she has some say in what is happening, even if it was only WHAT??, or even if it was only HEY!! You have to have some say in what's happening, even if it’s just, “what the hell is going on.”

You know, you lose so many things in a book like this, because you're really weaving a fabric, you're not making a final structure, so you can put something in at a certain point and it won’t change the overall fabric of the book, which is what I really like about a form like this. But I had a long thread for a while that was just about the people who obsessively followed the Mueller investigation, where it’s like, Where did that time go? Where did the time that people poured into that narrative go? And you saw, actually, a lot of novelists and writers were very invested in what was going on with the Mueller investigation, because it was an attempt to follow a story where we were trying to figure out what had actually happened. There’s some investment in this being a narrative that could be understood. And you just think it was followed minutely, day by day, every single development from the pee tape onward, and people were reading the newspaper of this every single morning of their life. And it was like, Where did that time go? Where did the time go that we poured into that dread of what was happening?

A person so inclined could read parts of this book as this account of all the ways the Internet can poison a fine mind, but then on the other side of that, it’s also a kind of love letter to the communal mind. There’s a bit I wanted to ask you about, where the protagonist sings “If I Were A Bell” to the baby, and the baby just loves it (“the baby pedalled her legs with excitement, she gripped her fingers with both hands, she cooed and she cooed on the same pitch, she pushed her oxygen mask away and then clutched it to her face”), and then after the song, she reads the baby Marlon Brando’s Wikipedia entry (“Nothing useful, but one of the fine spendthrift privileges of being alive—wasting a cubic inch of mind and memory on the vital statistics of Marlon Brando”).

I mean, that is being alive, that sort of ephemerality. That's wealth—that's like us splashing around in the pile of gold coins like Scrooge McDuck, right? That's the excess that means being alive.

Obviously, large parts of the second half are autobiographical. When you do something like that, when you read a baby with a terminal illness Marlon Brando’s Wikipedia entry, what else are you doing? You're introducing her to the world, but you're also bringing her into your own mind and your thought process. And if what you're doing at that point is really paying attention to how her brain works, how she thinks, you're carrying her just a little bit into yours and showing her around.

My sister and I talked a great deal about this concept of showing my niece around, that we would carry her with us through the world when we travelled, that we would show her things. And you could do that just a little bit with the Internet as well. There's a section where it's like, What did she want the baby to know? You want her to know what it's like to go into a grocery store on vacation, what it means to wake up at 3 a.m. and run your whole life through your fingers. But you also want to show her the Internet just for a second, just to show her what we've done, how it looks when we all think together.

So the takeaway would never be, we all need to drop our phones into the river and walk away from this. It did make it more difficult to be online in the way that I had previously been, in a way that felt like I was just pouring my life down into this window. But then there was also this other aspect of it, which is that this is how we think now.

It is my responsibility to show people around, to show them what I'm looking at, in my own mind. And then you still have these days where it rises up in that hysteria where you’re reminded of why we started doing this in the first place. Like when all the Republicans in the world got coronavirus—it had this strange sense of an earlier Internet. Not because you want people to be suffering, but just because they have weaponized what was happening in this country to such an extent that hundreds of thousands of people were going to die who did not have to die.

There's a sort of release, this hysteria. And it was all people thinking the same things at the same time. And that, I don't know, it's powerful. You don't want to absent yourself from that entirely, I think, or I wouldn’t want to, because it is part of how we live now.

But no, I was not able to be present in the same way. And I think that is what I was trying to set down, or what I was trying to talk about, because it's not that these things that we do are beyond criticism. We build these citadels, these amazing pleasure palaces, and we should also look at what goes on in them—how they work, who are the workers who are suffering at their hands, who’s doing the landscaping.

There’s a part in Priestdaddy that I love where you say, “There is always someone in a writer’s family who is funnier and more original than she is—someone for her to quote and observe, someone to dazzle and dumbfound her, someone to confuse her so much she has to look things up in the dictionary. That would be my sister Mary, who I worship as people used to worship the sun.” In this novel, which as you’ve said is largely autobiographical, there’s that same kind of love and boundless admiration that the protagonist has for her sister. What are the considerations that go into that writing process, when you’re drawing on your relationships with the people closest to you?

I mean, I have a big family. It's always going to be that way—that if I write about the things that happened to me, I'm also writing about things that happen to other people. My life touches on a lot of other lives. But I like the idea of being able to write straightforward love letters.

I think that the first half of the book is really writing about the protection that we've armed ourselves with, because we are under attack by the world, so there's this irony that we've armed ourselves with, this satire and these jokes. It felt important to be able to show those, and then for the protagonist to walk into the second half of the book totally unprotected and to say, what if these things don't protect us?

I shouldn't feel embarrassed about writing something that is absolutely straightforward and sincere. And I think one of the things that the portal can do is it can make people embarrassed to talk about things that really happened to them in a very straightforward way without any sort of protection.

I felt that the one thing that I had to do was absolutely lay out this love letter as I felt it. If you're writing about the way things are in the portal, that's a kind of truth. But if this is a love that you have in your life, that is also a truth that you have to report on.

I talked to my sister about it, when all this was happening. And I said, I'm writing this book. And then, suddenly, I began writing about the baby. Of course, if it had been a problem, it would never have seen the light of day, but my sister—my family in general—has always been very, very generous to me in that way. My sister told me that she would never tell me what I could write and what I couldn’t write, but for her, it was also the idea that maybe now people would know about this child as well.

When you think about the things that will disappear if you don't write them down, a little life can disappear from view. It's not always your job to present it, but in this case, I felt absolutely called upon to just witness a small and different life, and to do it the best that I could. It was almost vocational. And for my sister, I think it brought her a certain amount of comfort, just to know that the baby would not be forgotten, that she would exist in this form.

You do have to be responsible, but I think part of that responsibility ought to be that you should tell the truth, even if it leaves you unprotected, even if it leaves you very vulnerable.

What made you choose the epigraph?11From Mayakovsky’s “I and Napoleon”:

There will be!

People!

On the sun!

Soon!

The same thing that makes anyone choose an epigraph: you happen to be reading it and you think, “Hell yeah.” Mayakovsky also seemed to be particularly tuned to the moment, a person who rhymed with current history—a practitioner of absurdism whose language was increasingly bent by the weight of the age. There will be people on the sun soon—it felt as if we were already living there.

What’s your writing routine like?

I write in the morning; I begin by reading a book and I wait for the trigger point, which is what sets you off on your own work. It is different now because I do write criticism, so a lot of times what I write in the morning, and what I read in the morning are books that I'm reviewing. And then from there, I will move to my own work. This year has been a little bit different—I think if I hadn’t actually gotten coronavirus, lockdown probably would have been perfect for me, I would have just been in absolute hog heaven. Like, I don’t have to go anywhere, I don’t even have to go on a book tour? I mean, I like going on book tour, but when I went on book tour for Priestdaddy I got three different flus on three different continents. It was tiring in a way where you’re like, How do people actually do this? So if there had been this opportunity to be not allowed to leave my house for a year and do a bunch of Zooms I would have been so productive—but sadly, coronavirus did get in the way.

I really probably write and read a lot more than is healthy. If I plotted it out it would be like 10 hours a day—not great. But I have started, because I had some memory issues after I got ill, I got this HUGE moleskin notebook that is serious business. It’s enormous and it has all the different area codes of all the countries around the world at the beginning. So I write so much more information about my day-to-day life now than I previously did, which has been kind of interesting—I've never kept a diary or anything like that. But I'm actually getting a lot of writing done as I recuperate just because I'm like, Well, I need to write down the movies that I watched, or, you know, what takeout we ordered and things like that, just so that I remember in the future what was going on.

But yeah, I always start out with a book in the morning and a notebook and I just sort of write down what I’m thinking and then at some point you just you just lift off, and then you go.

What have you read lately that you’ve loved?

I’m rereading Astrid Lindgren’s Seacrow Island at the moment. Recent books I’ve loved are Andre Gide’s Marshlands, Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters, William Carlos Williams’ The Doctor Stories, and Elsa Morante’s Arturo’s Island.

Explaining a joke is killing a joke, obviously, but why is it funnier to spell it “sneazing” rather than “sneezing”?

See, that's not even explaining a joke. That's a mystical question. This is almost getting into a religious question—we could base a religion on why it’s funnier to spell it “sneazing.”

I place a lot of importance on the way letters look, so the "A" opens us into a broader area a little bit. “Sneezing” is funny because it's so constrained—the look and sound of it. But there's something, with the “A” right in the center there, where it almost feels like it glitches and just opens up into this big bubble and releases us into a field. We see something going wrong in the word, and a part of what's funny about a joke is the element of surprise, right? It’s this moment where something goes wrong, or takes us in an unexpected direction. You can pretty much always do that with a misspelling, but in order to be a truly funny misspelling, it has to look close enough to the original—S-N-E-O would not be funny, S-N-E-Y wouldn’t really make sense. It has to be as close as you can get, but also as far as you can go while maintaining the verisimilitude. Part of it is just I think how it looks.

The early experience of Twitter was so much more about, like, finding the most hilarious misspelling. We have almost completely left that behind, which I think is really sad. It was much more ascendant, I think, before there were images. As soon as there were images, then images could do their own work. But before, we had to include images in the text itself, and misspelling was one way to do that. It was just like adding another dimension to it. But, I mean, think about it: is there another spelling of “sneezing” that would be funnier? Not really. I think we found the one.

So that’s sort of my best guess at the “sneazing” thing. I feel sad that we have lost the misspelling era, because that was fun. It was like playing around with the blood of the alphabet itself, and I really liked that.