Like Jeremy Atherton Lin, I don’t remember my first gay bar. It might have been the one I went to in Tel Aviv when my cousin was visiting, where he and the boy who was my first kiss flirted in broken English and Hebrew, or maybe it was the lesbian night at a too-fancy place where everyone was older than my friend and me and seemed to know each other. Easier to recall are Stonewall and the Cubbyhole in New York City, where my best friend and I tried and failed to get picked up, or the now-shuttered Babylove in Oxford, England, the place I still think of when I fantasize—especially recently—about the joy of anonymous dancing bodies pressed up against each other, which in Babylove included sweating walls painted red, a mix of contemporary Top 40 and disco playing on the crappy sound system, and too many straight girls distracting their gay friends from cruising.

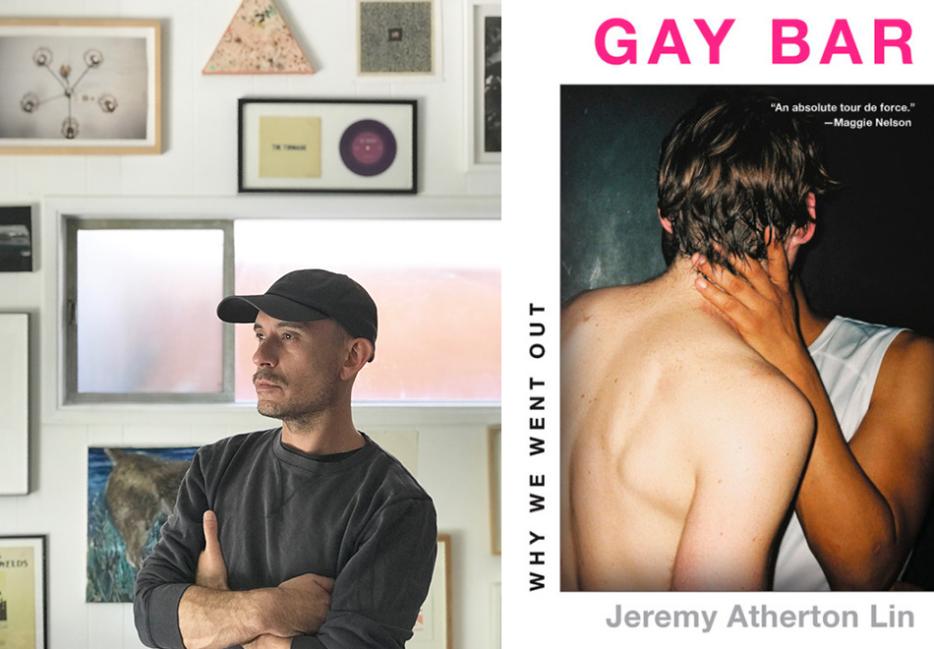

All of which is to say that I have a nostalgia for gay bars that doesn’t really belong to my experience of them as a millennial queer who presents more like an Old Navy mannequin rather than a butch or femme. My yearning is tied instead to the idea of gay bars, which was why I was so excited when I learned about Atherton Lin’s debut, Gay Bar: Why We Went Out (Little, Brown and Company). It’s a difficult book to categorize—a cultural history and a critique, an examination of a distinct set of places, and a memoir of sorts, all rolled into one. This isn’t the definitive take on the history of the gay bar as an institution, but rather a deep dive into specific gay bars that Atherton Lin frequented or experienced during different times in his life. Through these specific places, we learn about the history of the concept and the ambivalent nature of such an endeavor: do you go to a gay bar to be more gay or less gay or something else altogether? The histories of these places of business are ultimately histories of people, as well: gay bars have been community hubs, gatekeeping clubs, cliques, comfortable homes away from home, mediocre drinking spots, and so much more.

I spoke to Atherton Lin on Zoom recently about his book, the limits of categories, TikTok, and more.

Ilana Masad: Gay Bar is bookended by this concept of gayness being an “identity of longing.” Fantasy is thus an inextricable part of it, right? I wonder, how do you think we (gay people, queer people) fantasize about the gay bar as a space, as an institution?

Jeremy Atherton Lin: I think a lot of people who are younger than myself presumed that I was working on a project about queer spaces. And I think even though I put forward these ideas about there being this kind of longing embedded in gay identity, I'm also very much not a utopian writer, so the places—many are problematic in various ways. The gay bar as a fantasy… I guess the thing that comes to mind is there's an Erase Errata lyric about this bar in Oakland called the White Horse, how the White Horse is beckoning you toward a night of gay dancing. And for me—I'm answering this in a more personal way—I suppose it's always been kind of like about that promise of what the night holds in store.

I grew up in the suburbs, in Northern California, so to me, the idea of engaging in these social environments has always involved a remove. I remember being a kid and being in the side yard of my parents' house. And as I got older that involved smoking cigarettes—menthols, cloves—and looking at the search lights across the sky. I had this vision of them being for movie premieres, like they were coming in from Hollywood, but they were probably from used car lots in East San Jose, California.

Amelia Abraham makes this point in her book, Queer Intentions, where she's like, all the gay bars are closing—is it my fault? I haven't been going as much. I think June Thomas wrote about that in Slate as well. [Gay bars] are monuments in a way, monuments in a cityscape. And then there's all these challenges, right, in a newer generation of spaces. How do you create eroticism in environments where there are these kind of edicts about behavior? There are places that achieve it to various degrees in various ways.

By the same token, in London, there’s a sort of a mediocre gay bar that I think is valuable. Of course, for every gay bar that's in the book, there were dozens that I couldn't put in, but in the back of my mind was always this one type of gay bar that you might find yourself in that represents something very much more practical than this fantasy that we're discussing. There might be a person who is slightly gender variant in their behavior, and doesn't feel comfortable in their workday and just has a place to go where they can unwind or let their figurative hair down. I think that there's like a real value for those, and those are also often safe spaces for women of a variety of sexual orientations.

One of the things that struck me most toward the end of the book is your contemplation on safety. Gay bars were, and still are, places people go not always to feel safe, but also to feel the thrill of physical and emotional risk of some sorts. You write about how some queer spaces are requiring rules of engagement now, are trying to be safe and delineated. Is danger something that can only be enjoyed from a place of the relative safety that comes with privilege that you learned you had? (I know this is… complicated.)

It is, and it’s a quandary on a personal level, too. On one level, especially from the outside looking in, as a cisgender gay male, there is a level of risk that I’ve had the privilege to engage with that maybe people in more vulnerable bodies haven’t. And gay male socializing has often been more public, historically. The quandary for me is that if I have a friend who’s been slipped a roofie or somebody who wasn’t able to figure out how to reconcile and express consent in a group sex scene that involves chemicals and so on—[it becomes clear that] every body can be a vulnerable body. Certainly I understand the need for spaces that have boundaries that prevent a kind of tourist who verges on predatory.

But this starts to leave the bounds of what I’m comfortable talking about, because at some level these can’t be my spaces. Like in London, before lockdown, there were events where you had to be a person of color to get through the door, they were for QPOC. And, of course, there are thoughts that go through your mind, like: my partner is white, am I his passport into that space? Or do neither of us go in? A part of it is that there are more theoretical terms that are then being put into places that are not theoretical—they have to be equipped in case of fire, and people are intoxicated and wound up and anxious and all this stuff. So how do you reconcile the ideals and the reality? I'm aware that in London there have been a series of parties with regulations about who gets in, that emphasize femmes of color and trans people of color, with a door checker. [These parties] are reported to be completely sexy, hot, fun environments—so there’s a space where those regulations might be necessary so that the party can be sexy. But then I suppose there's this other problem, about what’s legible at the door.

The thing that makes me a bit nervous about speaking to this is like, I don't really have experience in nightlife as a service person, and my position is always slightly that of a wallflower. My sister finished the book and she was like, you can never make up your mind in the book. You're slightly on the outside.

One of the things that really resonated with me on a personal level was the way that you talk about going out basically for the story. Yes, for the experience itself, but also because you get to talk about it after, you get to think about it after, you get to write about it after. It’s almost like it’s about the eroticism of the mind at that point, right?

That totally nails it. Yes. If these had been safe spaces, I wouldn't have had a lot of the anecdotes in the book. We're in these kind of intrinsically solipsistic zones now because online engagement is all centered around us, and we choose where we go and we're often in echo chambers. So there’s this three-dimensional thing that you lack, which is the experience of feeling slightly uncomfortable and yet forgiving towards a stranger. An example would be this older generation of drag queens in London whose jokes are not always very contemporary, and you might engage with or watch somebody perform in these spaces and your tolerance for their button-pushing keeps getting tested a little bit, but you're also with another person who might have a similar feeling to you that you can share a sidelong glance with, or you might leave with a continued ambivalence towards the experience. So that, or—I mean, this is kind of dangerous territory to go into, but personally, there are moments where there’s physical contact that might be a bit ambivalent, and that can be both a turn-on and something that makes you feel vulnerable.

You just mentioned the online spheres that we're in, and in the book, you quote a regular at Studio One who spoke to the LA Times in 1976 who prognosticated, as you write, a dystopian future in which the gay bar would be a space where “each of us will go into a space the size of a telephone booth and dance by ourselves.” That honestly sounds like a lot of gay TikTok. How do you feel about that solipsistic evolution, especially now, during the pandemic?

There was an article in the New York Times recently with the headline “Everyone is Gay on TikTok,” because they're very performative. And then I started thinking, oh my god, like, this is all these young men have right now, that kind of “like-hunting” by showing their underwear and so on. I was saying earlier, I grew up in the suburbs and in my friend group, we felt very much like there was a wall between us and popular culture and that we were always there to tear it apart, this intimate coterie of friends who saw some things with a similar sense of humor and saw the absurdity of things. So that remove feels in a way quite normal to me, I'm quite used to that. But the fact that that's all there is… I don’t know. It must be so hard to be young right now. With TikTok there’s this brevity and a lack of dimension and proximity. It's just that lack of being with another person, breathing the same air, you know, and the idea of engaging with somebody's body language and all the nonverbal cues that you give.

The first period of this pandemic wasn’t that difficult for me to adjust to as somebody who's happy to be at home. I'm lucky to have a safe—and not only safe but nurturing and convivial and humorous and jolly—domestic environment. But now, these kinds of questions that we're talking about—I think the ramifications of them are very significant, because they have to do with humility and dialogue and forgiveness and ambiguity or ambivalence a lot of the time, and being able to continue to have mixed feelings about the environment that you're in or a person you're engaging with. I think it's quite unsettling to me.

Capitalism, and its effects on gay liberation and on the post-gay attitude, is a prominent theme in the book as well. Gay bars are places of business, after all, and you make the point of writing about how gay men—especially gay white men—have long had a particular relationship to how real estate investors look at a neighborhood. How do you see the market affecting (or interacting with) gay and lesbian and queer people today?

You know, it took a while for it to sink in that I had chosen a subject matter that is comprised of private businesses. And obviously that starts clicking into place when you have to make sure that you're not saying the wrong thing about a place. It's funny because in a way there’s a paradox where there's a kind of activist movement about the preservation of these private entities, and it can be the case that preservationists are at odds with the interests of the owner of a business who might not want it historically listed, or might want to sell it and isn’t particularly invested about whether the next place is a queer space. I quote Gail Rubin talking about how we feel proprietary towards these spaces, but at the same time they are businesses, and, in fact, in various ways have monetized a scene that outside of capitalism might've found some kind of other form to take.

I make a joke in the book about how it feels so realpolitik, but it was clear to me that there needed to be an acknowledgement of the fact that [capitalism] has been the structure that certain undeniable progresses have occurred within. I was trying to consider the reality of that socioeconomic framework and what happened within it.

And that hasn’t ended, right? The relationship between capitalist consumerist culture and liberation. You see commercials with gay people in them now and you smile and say, Oh, that's so lovely, but then you also remember after a while, Oh, right, I'm being sold to, I'm being used.

Yeah, and some of the more progressive language around identity is often quite adjacent to expensive moisturizers, and sort of the makeover as a ritualistic act that also has several specific brands attached to it and so on. I think what I'm trying to inhabit in the book, which just feels very natural to me, is the perspective of somebody who just isn't quite certain about what the solutions to all this might be and to convey what it is to be feel conflicted.

I think we hear a lot of voices of people who are very resolved and confident and assertive about these things. I don’t know, maybe I'm wrong, but I feel like you less so hear from the perspective of a kind of uncertainty, or an admission of where your more idealistic side of you abuts against some desire for just feeling safe and comfortable.

I love that you’re conveying your uncertainty about this even in your response—“correct me if I’m wrong.”

Speaking of language and uncertainty—the book is gorgeously written, and I noticed all these elements of reclamation in it. For instance, you call Sir Ian McKellen a “swish,” you joke about limp-wristedness, and in general, you make the point of using terms that have been weaponized against gay men especially. At the very end of the book’s notes, you included a disclaimer: “Where a description of a person or group is not self-identification, it’s based on cultural and geographical context. Contemporary terms are not used for historical figures except as deliberate wordplay. Lingo is not always ideal or neutral, but reflects the experience of the moment.” Would you tell me a little bit about how you were thinking about language as you were writing this book?

It’s always a test between what would be the language of a given moment and caution. I know there's a lot of things that you're not supposed to say, but that people joyfully and with a sense of self-empowerment use as self-identification. But then you obviously consider your impact in the world and you don't want to hurt other people. But it was important to me to—you know, in the chapter about meeting Michelle Tea and her partner Rocco—it was important for me to convey that moment of exploration, which very much involved a reclamation of pejoratives [in this case “fag”].

Language also changes in different ways in different places, which is why I included the excursion to Blackpool in the book. I didn't want to go into this book as a journalist, although obviously it crossed my mind that there's this longest ever running gay bar in Copenhagen that I should visit, and a place in New Orleans, and a church-themed gay bar in Athens, Georgia. But everyone who knows me and knows what I do said it has to be about how these different spaces have formed me, because that's my kind of strategy and way of thinking. It's almost like that Blackpool section is a bit of a test about what happens when I then go all Didion on you and visit in search of a story. [Blackpool] is an example of a very working class, to some extent regionally self-contained environment where the language is going to be definitely different.

It’s been quite a heavy experience for me to try to balance. I'm trying to respect everybody. Every acceptable word actually has the potential of erasure as well. And like, you know, I'm supposed to be gay, officially, according to GLAAD, but sometimes it's homosexual or, you know, like I say in the book, fag feels actually very comfortable to me. Every word has its issues, but then there's been a [mainstream] consensus and I do struggle with that… You know, some forms of sexuality are pervy. And I think that there's been a kind of erasure of the pervert. There’s a kind of essentialism then about how you are valid because your sexuality isn't dirty, and then there isn’t a place for dirtiness and finding playmates in perversion, you know?

Absolutely, that’s really real. So speaking to the way that you think: Gay Bar is about place—like your journal Failed States is about place—but it’s also about the ephemerality of place, its changing nature, its inability to remain the same no matter how much we’d like it to. What sparked your interest in how history and experience is written on the body of the place, with and through the bodies that occupy it?

You know, I think I need a person, place, or thing to hang onto [when I write]. There’s a Lydia Davis story, “Foucault in Pencil”, and her narrator in this story is in a waiting room for a doctor and is reading Foucault and then takes the Foucault onto the subway. It dawns on her that she loses the plot of the sentence if the subject is “absence” or “law” or “power,” but she can keep through to the end of the sentence if its subject is “wave” or “door” or “penitentiary.” I think that way too. I just need something, sometimes literally concrete, to hang onto.

It's interesting for me to take on quite a big theme like I have with this book because I [usually] write in a minor key. I consider myself a miniaturist in a lot of ways and my favorite writers are people who write in a small voice or occupy a small space. So engaging in the actuality of a space just keeps it making sense to me. I'm like that with my students when I teach—they'll tell me that they want to write about authenticity and I'm like, can you just tell me about this favorite pair of jeans of yours, because we'll get to authenticity [through that]. Different people think in different ways, but a lot of times I recognize that somebody might, like me, learn that way.

I also really want to be learning while I write, and I think when I am successful is when I'm taking the reader and we're learning together. A teacher of mine talked about writing at the edge of your reach, like just at the grasp of your fingertips. So yeah, there's a part of me that would like to write about place and literally just be like the cobweb in the corner of the room, but then there's something else where I feel compelled to learn while I'm creating the book and hoping that that becomes a part of its presence in the world.