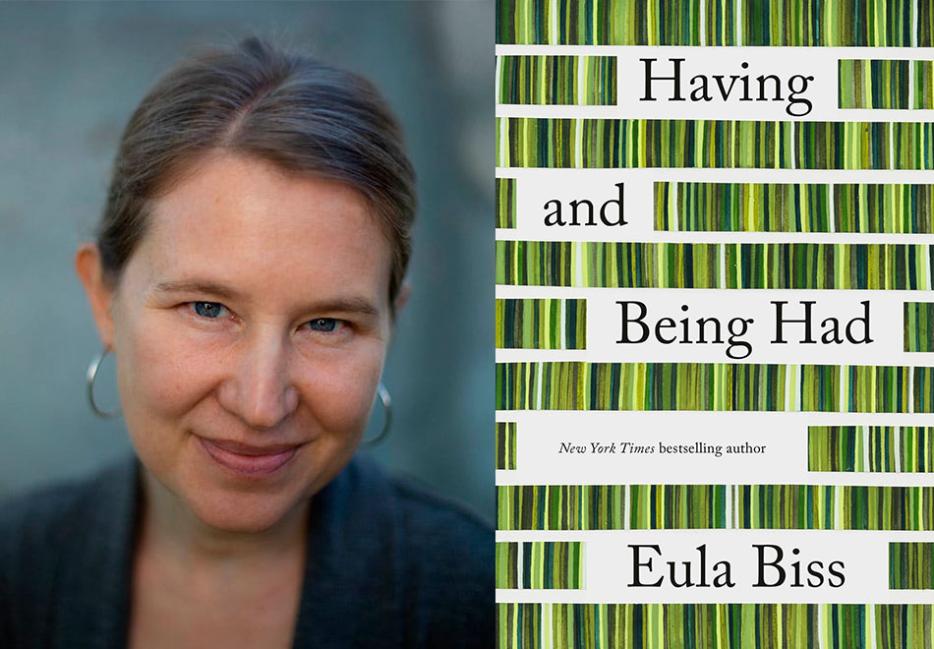

In Having and Being Had (Riverhead), Eula Biss wonders if she’s on her “way to becoming an asshole.” I wasn’t sure what to expect when I called her to talk about the newly released book. In articles, interviews, and lectures, the author is often introduced with a long list of accolades. It’s both impressive and boring, the way the recital of prizes, awards, and fellowships precede her ideas. I figured my preamble would be different, but I still seem to be drawing attention to the fact that Biss is highly acclaimed.

It’s not Biss’s distinction as an essayist that made me unsure of how our conversation might go. Throughout her four books, the author presents a complex self-portrait. And yet, it wouldn’t work to classify Biss’s output as autobiography or memoir. This isn’t so much due to the writing not fitting the definition of those terms, but rather that the prose is too varied in its scope, approach, and presentation for standard designations. She’s described herself as a “poet who writes in prose, or a prose writer informed by poetry,” a flexible taxonomy that exemplifies her style. Her writing is often beautiful and marked by a shrewd self-awareness. She’s a clear, deliberate thinker who sinks into her discomfort. She discloses and critiques, and she’s fine if you disagree with her. She would likely be disappointed if no one did.

Her honesty can make me cringe. In one of her new essays, she tells of visiting a laundromat to wash a comforter. When she finds out the machine is broken, Biss—whose new book is centered around purchasing a nearly $500,000 home that she and her husband live in with their 11-year-old son—asks for her two quarters back from the attendant, “out of principle."

I dial her up and she asks in a friendly, disarming tone, “How is your pandemic existence going?” I tell her something nonspecific, that it’s weird and I hope it will be over soon but that I don’t think it will be. She says, “I think we’re in for the long haul, like a couple more centuries of this struggle, but it's a struggle worth having.”

As someone who strikes me as particularly protective of her time, Biss doesn’t seem to mind when our conversation extends well past our allotted hour. It could be that being the subject of an interview has its charms, but it’s not as if Biss hasn’t had an abundance of opportunities to talk about herself throughout her career. Instead, I get the impression that she’s genuinely interested in talking, affable even. With generosity, she fields my questions about capitalism and writing, and it’s apparent she has thought about both subjects a great deal without becoming intellectually fixed in place. Her worldview has a certain open-endedness to it. While her writing contains many internal investigations, whether or not there is a straight answer is typically neither here nor there.

Andru Okun: I wanted to start by acknowledging the passing of David Graeber; his writing plays a significant role in Having and Being Had. I’d like to hear your thoughts on how his work influenced your own.

Eula Biss: It’s such a devastating loss. I haven’t fully assimilated what the loss means for me and my work and my thinking. Although I haven’t finished reading all his work yet, so I feel like I at least have that remaining. What I really appreciate about Graeber and what I value about him as a thinker was his skill and ability to put really nuanced, complex ideas into clear, straightforward, and often beautiful writing. There are moments in his prose that I think are transcendent, poetic really. You can read him without feeling like the prose itself is throwing up barriers—which is how I often feel about academic work or theory. I have neither the training, sensibility, or inclination for that kind of writing. I struggle through it when I need it and there’s an idea or concept I know I need to familiarize myself with or work through, but sometimes I get really angry when I’m reading work like that because I feel like the author could have done more to bring the ideas to the reader.

Part of my tremendous gratitude to Graeber is all the work he did to bring his ideas to the reader, to us. And his ideas don’t float free, they are always nested in a really complex and often fascinating thicket of research and information. Like in Debt: The First 5,000 Years; I had been avoiding it actually. People had been recommending it to me for years by the time I read it. It didn’t sound like a book I could possibly enjoy, and its size also intimidated me. I ended up reading it three times, and I think I listened to it one time on tape. It was a pleasure, his prose itself, the way his ideas move from chapter to chapter, and even internally within chapters. There’s a really elegant organization of ideas. He has a really amazing piece on consumption that I wrote about in Having and Being Had that I’ve probably read a dozen times. The deepening of his investigation and the layers of meaning that he’s navigating is just so dazzling to me, as both a writer and a thinker, that it never gets old. I could sit down and read that piece right now and find something new in it and delight in it all over again and feel awe and newly educated by it.

That’s how I feel about Baldwin too. I’ve taught Baldwin’s “Notes of A Native Son” for nearly 20 years, and every time I return to that essay I find more and I glory in his artistry and I learn from the sensibility on the page. I feel like these thinkers who are also sensitive to the written word and the power of clear prose are tremendously valuable. Recently my partner floated this idea where he asked if the ideas of people like Marx or Freud would have ever taken off in the way that they did if they hadn’t had a way with words and with metaphor and knew their way around a sentence. I think that’s a really interesting question. What if Freud wrote in the kind of prose that is typical to the academy today? Would his ideas have ever caught like wildfire the way they did? I kind of doubt it. That’s probably as far as I should go—I don’t want to get too deep into disparaging academic prose.

One thing that is noteworthy about Graeber’s prose is that it’s written less from a place of strict craft and more from a place of praxis. The politics are meant to be accessible and the language follows suit.

There’s an ideology there, one that I happen to share. I do believe that every aesthetic has its ethical and moral dimensions. As an artist, as a writer, I am extremely dedicated to a particular vernacular, and for reasons that feel very political to me. I think I sense a similar aesthetic stance [in Graeber’s writing] and respect it, even though I think aesthetically speaking we work in different worlds. I don’t think that someone would look at us and say that we share an aesthetic, but I think that in the place where that sensibility meets an ideology we share an aesthetic and a value system around what language can do and can be for, how it can be used.

I like this expression: “Sensibility meets an ideology.”

I think this might be an entire area of philosophical study. My sister is a philosopher and a professor of philosophy; one of her areas is the intersection of ethics and aesthetics. So I only know through conversations with her that it’s its own enormous area of study, but it’s also through those conversations that I gained an appreciation that there is a theory out there that every aesthetic stance is also an ethical stance to some degree. That’s why people get so fucking passionate about their aesthetics. At one point I was in a bar in Chicago for a poetry reading and a poet punched another poet. It was over an aesthetic disagreement. We come to blows over aesthetics! I think the real underpinnings of our aesthetics are ideological and ethical.

When asked to describe your writing process, you once stated, “It looks a lot like doing nothing.” This reminds me of something you write in Having and Being Had: “I think it’s a gift to give another person permission to do something worthless.” Do you see these ideas as related?

Yes, related in that the work of artmaking can often be illegible within the logic and everyday practice of capitalism. It’s one of the problems for an artist within this particular economic system: our work often doesn’t look like work and it’s not compensated like other work. Its value isn’t measured in the same way as other work. I think that can have a profound psychological effect on an artist. It’s one of the things that can lead to the kind of despair that I think is unique to an artist living within this particular economic system, a despair that comes from dedicating your best energies into something that is routinely undervalued and not seen or understood as work. I was joking a little bit when I said, “It looks a lot like doing nothing,” but it actually does. That’s an accurate statement. It can be hard when there are other commitments and demands pressing in on your life to insist that you must do nothing. When there’s so much to be done and culturally there’s so much encouragement to fill every moment and be busy in a way that is legible to others, it can be hard to insist that it’s absolutely necessary to your life and endeavors to do nothing. It can be hard to justify, especially if you’re living a life that involves the demands of caring for other people. That sort of work can take as much time as you’ll give it. It can be hard to say, I'm now going to pause in the work of caring for other people to do what appears to be nothing, but is actually incredibly essential to my work and development as an artist.

When I’m teaching, especially at the undergraduate and introductory level, a lot of my work is about teaching the sensibility of an artist more than the craft of an artist. The craft comes in as well, but at that introductory level what I’m often introducing students to is a stance—a stance towards your own work and a mindset that, to some of my students, is entirely new. For some people it’s more of a struggle than others. Some people really have a hard time wrapping their mind around how work that doesn’t earn any money can possibly be valuable. Other people have no trouble at all with that concept and have already lived it to some degree.

Bits and pieces of your earlier writing reanimate in your latest book. I notice pianos, Dracula, a German cabinetmaker—Joan Didion makes multiple appearances throughout your published work. Do you find yourself intentionally returning to symbols and concepts or is it more of an instinctive process that leads to their reoccurrence?

It’s both, but in this particular work I was engaged in a very intentional, sort of mid-life retrospective reckoning. That encouraged me to look back on former work and engage with it and sometimes make fun of it. The title of one of my essays, “All Apologies,” comes up in a setting where in my mind I’m making fun of my earlier work. In this piece called “Right White,” I’m kind of teasing my own over earnest stance in that previous essay. It’s probably more or less invisible to most readers, but I’m taking a dig at myself and engaging in a little self-critique. At some point I understood this book as a conversation between my nearly 40-year-old self and my 20-year-old self. I wrote my first book, The Balloonists, when I was around 20. [Having and Being Had] is in some ways, formally, a return to my interests as an artist at that very early point in my development and career, where I was engaging with prose poetry really directly and playing with genre, messing around on the border between poetry and prose, doing a kind of mash-up of autobiography essay and poetry. I think I return to that artistic sensibility while trying to talk with my former, earlier self and her ideologies, because the life I had just stepped into would have been very foreign looking to the me of my 20s. I think I was asking myself if my value system had changed: Has what matters to me changed? Have I sold out? Or is there some continuity in what matters to me? Am I making different decisions on a practical level than I was in my twenties? Or is it that I’m finding new ways to support the same values and ideas that I was trying to support at that time in different ways? Those were some of the animating questions of this book, so I think that did draw me into conversation with my younger self and my earlier work.

Do you feel like you answered those questions?

Oh, you know. [Pauses] Not fully. And to be honest, I never feel that I fully answer the questions that are most important to me. The questions that are really important to me are the questions that feel like they contain a lifetime worth of work. I rarely take up a question that I walk away from feeling satisfied, like, Ah, I really solved that one. What I think I’m always going for in my work—whether I’m writing about race, motherhood, vaccination, public health—I'm always trying to reach more clarity than I started with. The project is less answering the question than coming out clearer and gaining some lucidity. I do feel like I came out clearer on those questions I was just mentioning. One of the things that I learned in my 20s was that dwelling in financial precarity was going to take a toll on my artistic work. I did really intentionally strive for the economic security that would allow me to do my work as an artist. One of the things I came clear on is that no, I haven’t abandoned the value system of my 20s, but I’m unhappy about what I had to do to gain basic security. That’s something that in general is enraging about our country, our financial system, our lack of public safety nets— you have to become upper-middle-class before you have what I think of as basic financial security. And what I mean by that is reliable health insurance, a retirement provision, and the ability to send a child to college. Those are the three kinds of securities that I’d like to have, but for most people in this country to have those things you have to have an upper-middle-class income.

Has interrogating life under capitalism compelled you to live differently in any way?

It has. I wrote myself into realizations that changed my life. Some of those you can see evidence of in the book—you can see me mulling over whether to accept more precarity in my life and step away from my very secure and well-paid job at the university to take on a much less secure existence as a freelancer. I was very strongly considering quitting my job and becoming a freelancer, writing for a living, while I was writing this book. I eventually kind of split the difference. I wasn’t ready to totally let go of my access to a retirement account and things that I get through my salaried employment, so I went down to part-time, which made a tremendous change in my life. I took a large salary cut in order to do that, but it freed up an enormous amount of time for my writing. The thing that I didn’t know was going to happen, that I couldn’t have predicted—and this happens outside of the narrative time of the book, so it doesn’t show up—but in the very last scene I'm digging a hole and I decide to sell the book that I’m writing. And I do. What I don’t yet know in that moment is that selling that book will produce, at least for a few years, more income than I was making as a professor. That won’t last—this is the thing about book advances, they get used up, they’re not a salary, they’re spread out over installments. Then that money is gone, unless you get a similar deal, which can’t be guaranteed or predicted. Once my advance is gone, I’ll be back to a lower baseline in terms of salary. I essentially decided to make less money and to give less of my effort towards pursuing making money.

I was at an interesting turning point when I wrote this book; I could do something that was not an option for me during the previous 15 years of my career. I suddenly had the ability to make money off of my writing. That wasn’t an option for me for many, many years, in part because I was doing weird stuff. I was writing poetry and there’s just zero money in that. And then all these new opportunities got kicked open for me, and there was a moment where I was just working way too much. It was actually when I started the initial writing for this book. I was teaching full time and I was doing various kinds of promotion work for my previous book which had just come out, and I was parenting, and I was doing the volunteer work that I do in my community, and I was traveling a lot to do talks at universities and guest teaching at various places. I was essentially saying yes to every opportunity to make money. I developed migraines for the first time in my life. I didn’t stay in that space for too long, but it was really destroying me. There’s a repetition of the words “death” and “dying” throughout the book and it actually scared me when those words started appearing. I didn’t know why and I didn’t understand what their appearance meant in the book. The book ending on a grave was a little disturbing to me. [Laughs] I understood it as a metaphor but I didn’t quite understand what the metaphor was telling me. I’m still in the process of doing some of the interpretative work that happens after you finish a book. For me, the work is finished before I have finished understanding it, which I think is sometimes surprising to people who work differently. I’m still in the process of gaining a better understanding of why I did what I did in this book. I think that repetition of “death” and “dying” and the appearance of the grave is because I really did feel like that way of life where I was taking every opportunity to make money and letting money making be the priority in my life, that it was killing me. That it was going to kill me. Maybe not literally, but there was going to be an artistic death that I was unwilling to accept.

Notes from No Man's Land was originally published in 2009. Last year, you wrote about how the increase in conversation around white supremacy and white privilege made the book feel “new again, and newly unfinished.” Has the pandemic shifted your thoughts or feelings regarding your work in a similar way?

It’s an interesting question, and it’s such an interesting facet of aging as an artist in that my understanding of my work and my interpretation of it does not stay static. The events of the world definitely change the way I read my own work. I think that’s true for other people, too. My work is read differently now—especially my writing on race—then it was ten or 15 years ago. I’m not sure if I’m finished figuring out how the pandemic has changed my own understanding of my work. I think in both On Immunity and Having and Being Had, which I finished right before the pandemic, there were things I was exploring and trying to observe that felt subtle or unseen at the time of the writing. A lot of the work was seeing and acknowledging there was something in the shadows, hovering behind louder rhetoric. One of the things the pandemic has done is make many of those issues less subtle. Inequalities that were somewhat invisible—say, economic inequalities that people could happily forget about before the pandemic—have really been laid bare for us. And many people have made that observation, that the people whose work is most essential to our lives don’t have basic security and are not treated as if they’re essential to our daily lives. In a logical economy, in an economy that made sense and wanted to keep going, the people who were doing the absolutely essential work would be well supported and their health would be maintained. We wouldn’t be in a situation where people who are in a comfortable middle-class position like me are depending for their everyday needs on grocery store workers and delivery people who don’t have basic securities. I think that’s now abundantly obvious. I was writing in a time when it took a different kind of work to see that. I think that some of the observations that I was making, like in writing about Virginia Woolf, I was thinking about her vexed relationship with her servants. But I was also thinking about the way that we (meaning the middle-class) still have that relationship. We’ve just outsourced it, in part so we don’t have to live with it or look at it. Amazon has now replaced the role of the servants in Virginia Woolf’s house. In her time period, a middle-class person would have someone who lived in the house and went out and fetched everything, and now that is not the norm for middle-class people in this country. We don’t have someone in the house, but we still have people who do that work for us, we just don’t really look at them, think about them, or necessarily even talk to them. I think that’s much more obvious now than it was when I wrote the book. In some ways I think that the pandemic has set up this book to be better understood than if some of these things hadn’t surfaced.

You write that “the social cost of some things is their very cheapness.” Can you elaborate on that idea?

There’s a lot of thinkers out there who have looked at this with particular products or in particular areas. I think I once heard Michael Pollan on the radio discussing the true costs of cheap McDonald's foods, particularly the costs for agricultural workers but also the costs to the environment. The argument he was making was yes, this food is cheap, but it costs our society and our planet something, so really that cheapness is expensive, we just don’t see the expense immediately. There’s a sleight of hand going on. I was reading this other book, The History of the World in Seven Cheap Things by Raj Patel, a book that looks at a variety of things, including chicken nuggets. Those ideas really spoke to me and I think I’ve grown to be suspicious of cheap things. I wonder who suffered to make this cheap thing for me, basically every time I encounter something that isn’t expensive. Who got screwed? Was it the worker? The maker or producer? Where in the chain did somebody get shorted? This is what I ask myself. For me, there’s very little pleasure in what we would usually call a good deal. What’s usually a good deal for one person is a bad deal for someone else. I think that’s what I mean when I talk about the social cost of a cheap thing being its very cheapness. What we have to do to make certain things cheap is cheat people out of fair compensation, most often for their labor. There’s also cheapness produced by devastating the environment or engaging in a kind of monoculture. There are various strategies that can be used to produce cheap goods, but almost all of them are destructive and often in ways that are not immediately visible to us. Sometimes when I see these cheap products they’re vibrating with violence. It’s like an aura around them.

That is a devastating thought.

It takes the fun out of those little things that come in gumball machines.

You juxtapose prosperity with precarity, writing that “health is a mark of money in our time.” I think this statement is applicable to both people and places, but there was a point in time when this wasn’t true. When do you think things changed?

That’s a great question. I just need to pause for one second to let my son know there’s food on the table for him, but I will be right back. [Pauses] Sorry about that. I don’t think I have the knowledge or historical chops needed to answer that question, but I’ve read enough to stab around that question. Our medicine has gotten better. There was a time period where it didn’t do you much good to pay a lot of money for a doctor because doctors really were not doing a whole lot for people. In the era of what is called “heroic medicine” in the 1800s, you were probably better off using folk medicine than engaging in the expensive services of a doctor. We have now arrived in a time period where paid medical professionals are offering services that are extending people’s lives. Not everyone has access to that. There’s also the post-industrial impact around diet and access. This is talked about really beautifully in the book Sweetness and Power, this shift from nourishing diets to empty calories, lots of sugar, and little access to vegetables and nutritious food. That’s only one small component; I think there were all these simultaneous shifts happening. Right now, a certain kind of upper-middle-class lifestyle allows you to commit time to exercise every day, eat healthful food, access preventative medicine, and get cutting edge treatments. All these things are less accessible to people who have less money, but it is hard for me to say where that shift happened. I do think that once you understand that money can buy you a longer lifespan, you get greedy for more.

There’s also the reality that the process of acquiring money, which can be used to extend your life, can also kill you.

That is one of the saddest and most depressing things. When I was writing this book, I looked into some of the research about why there is such a gap in the US between the lifespans of the rich and the poor. Some of that is easily quantifiable and traced, and some of it comes back to things that are less quantifiable like deaths of despair. This is a term now: death of despair. Suicides of poor people are falling into that category now. The despair is partly economic, but it’s also the despair of spending all your energies on work that isn’t satisfying or personally rewarding. It’s destructive to a person in ways that take years off a lifespan. That was one of the most disturbing things I discovered.

What do you think are the benefits and limitations of using the personal or private to address political frameworks?

One of the limitations is that a lot of people won’t see or understand what you’re doing. A lot of people think of the personal and the political as two distinct spheres. I don’t. But if you do, it can put you in a position to not properly interpret the work. When I see my work misunderstood it’s often by people who see it as being about my personal life. I feel like I’m usually writing through or from my personal life, but I’m writing about something else. The way that I get to that something else is through my lived experience. But it comes up for me all the time that people don’t see it that way. That’s an obvious limitation, but I’m not going to write differently just because some people aren’t equipped to do the interpretative work that needs to be done. I’m going to write in the way that is most productive for me as an artist, and for reasons I don’t fully understand, to be honest, that often involves my lived experience.

I know you don’t use social media. I’m curious about what your media consumption habits or routines look like.

I fear that if I tell you about my media consumption it will seem to be the product of some ideology that I actually don’t have. I don’t watch TV. But I don’t believe TV to be bad and I’m not against TV and I don’t think there’s not great art making happening on TV. I went through a large period of my life, during my childhood, where I didn’t have a television. It’s not part of my rhythm or expectations. It’s something that I forget exists, essentially, even though I have a television now. Like, every six months or something I watch a television show or a series. I think I consume far less television than most people, but it’s not because I feel that it’s not a medium that is interesting. I also don’t see a whole lot of movies. I don’t do a whole lot on the internet except read newspapers. I think the portrait that is emerging is a really constricted engagement with media [Laughs].

But you have a smartphone?

I do. I put it off for quite a while, but in that period where I was working and traveling a lot I felt like it would really enhance my life to have a smartphone and to be able to read the newspaper on my phone and stuff like that. I read a few newspapers pretty much daily, but I’m not that sophisticated when it comes to media. I think that puts me at a disadvantage in certain conversations and probably puts me at a disadvantage as a knower and a thinker. There are things that I just don’t have access to. I find out about things after everyone else. I think being in grade school and not having a TV during a time period when television was the cultural touchstone accustomed me to being out of the loop. I’m not that uncomfortable with being out of the loop, in some ways that puts me in a useful position as an essayist because I’m informed differently than other people around me. I don’t necessarily arrive at my subjects with the same assumptions or the same information or having read the same critiques. I don’t think it’s all bad, but I’m especially aware of this when I'm talking to students and hearing what they’re learning and the kinds of conversations they’re engaging with, like over Twitter. Particularly Black Twitter, which is a really significant cultural presence. That’s something that I just don’t have knowledge of and that’s kind of a blind spot and a loss for me. But I also think this comes back to time; I make a lot of compromises in my life to have time for my work as an artist. That involves not engaging with various forms of media so more of my time goes towards creative production.

What do you think of this concept of “ethical capitalism”?

I don’t know. Can you tell me what that is?

[Both laugh] Oh, that’s a good answer. No. I guess the easy answer would be to say it’s bullshit or something.

[Still laughing] That’s not at all what I was implying, I just really don’t know what it is.

Me either. Obviously, your work addresses capitalism, but you’re also often talking about wanting to lead an ethical life. That’s an idea that goes far back in your writing. Maybe what I’m actually wondering is if you think it’s possible to live an ethical life under capitalism.

I think there are all kinds of ethical maneuvers that could be made within or around capitalism. And I do think it’s useful to be reminded that our system—even in the US, which is such a capitalist country—we do operate with other systems mixed in. We have forms of socialism and things like Medicare and Medicaid. Other ethics and practices can coexist next to and within capitalism, and it’s useful to remember that, especially because it does feel like an all-encompassing system and it can feel like there’s no way out. To circle back to David Graeber, one of the really exciting and inspiring things that he said is that we don’t have to invent alternatives to capitalism—they're actually right here and we’re living them right now. We just need to see, appreciate, and invest in them. The alternatives already exist, and to me that’s a really exciting idea. The tricky part is you have to live this alternative within the system. You don’t get to totally separate yourself, but I do feel like all kinds of ethical decisions are available to us, especially if you do away with some of the commandments of capitalism, if you stop working towards constant increase and expansion. That frees up a lot of energy and resources to devote towards things other than the pursuit of profit. But I think the ethical choice to not exploit other people’s labor is available here and there in a system that is essentially built on that principle. We still have opportunities to not exploit other people.