In 2005, novelist Lara Prescott came to Toronto to attend a Blue Jays game, where her boyfriend’s surprise marriage proposal was projected onto the JumboTron for all to see. As the crowd cheered, Prescott and her “fiancé” (who she in fact hardly knew) suddenly held up anti-KFC signs. The cheers turned to boos, and the JumboTron camera swiveled to something less inflammatory.

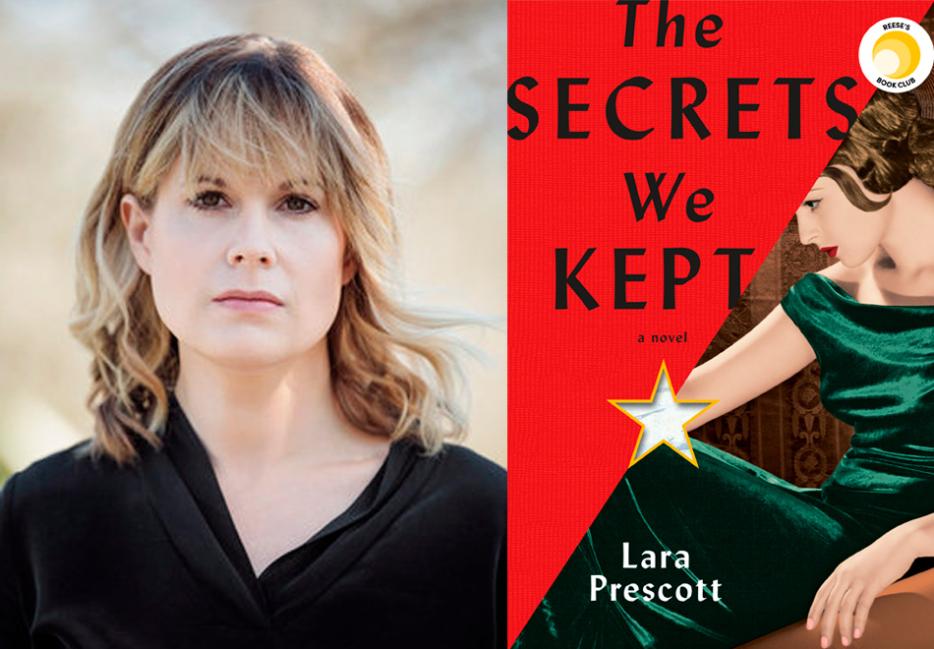

Prescott’s debut novel, The Secrets We Kept (Bond Street Books), seems a far cry from her youthful animal rights protests, but her interest in colorful resistance is at its core. The subject of a publishing bidding war and handpicked by Reese Witherspoon for her book club, The Secrets We Kept spans continents and decades to tell the story of Olga Vsevolodovna—Nobel-declining author Boris Pasternak’s lover, literary emissary, and the inspiration for the character of Lara from his banned masterpiece Doctor Zhivago.

Smuggled out of the Soviet Union in 1956, published in Italy, and eventually adapted by David Lean into a 1965 film starring Julie Christie in a fur hat, Prescott explores Zhivago’s secret history as a tool of political subversion, as well as the women who brought it to life.

Based on a real 1950s CIA mission that painstakingly brought Pasternak’s novel back into the Soviet Union, The Secrets We Kept feels like a literary answer to shows like The Americans and Mad Men: full of intrigue, undercover couriers, diligent typists, and true to its Zhivago roots, unrequited love. Prescott, whose mother named her for the character that Olga inspired, splits the narrative between East and West, marking the cultural differences between Stalin’s Russia and the sexism and sexual repression of Washington.

During her second visit to Toronto since her dramatic proposal-turned-protest, Prescott talks about her inspiration, her historical research, and how life sometimes imitates demonstration: years later, she married the guy who proposed to her at the Jays game, a love solidified by a mutual antipathy for corporate chicken. What could be more romantic than that?

Naomi Skwarna: Well, it sounds like you have a history of drama and politics.

Lara Prescott: Ha! Yes. I started getting involved in political activism when I was in college. In high school, I started learning more about the issues and volunteering, but in college, I got really involved in protests. This was back when George W. Bush was in office and declared war. It was a large part of my experience when I first moved to Washington—where I went to school. Political activism around animals and the environment. Those types of issues.

The characters in your stories, Sally and Irina, are also performers in a way. As spies, you write about how they use their roles as cardigan-wearing secretaries and typists to cover for their more covert missions. But it’s more than that.

Absolutely. There’s the role-playing that Sally and Irina do [as CIA operatives].

And even though there are risks, they find freedom in becoming someone else. I love the chapter when Sally is in Italy, preparing for the Doctor Zhivago book launch, and you describe how she invents herself for whatever mission she’s been assigned—right down to how she takes her coffee.

She really becomes the character. During my research, it was interesting to learn about actors and method acting—assuming characters. This was something that people who worked undercover also did, down to what would be in their pockets. So yes, I think I do have a long love of that kind of theatricality!

The story is split up between characters in the East (the Soviet Union) and the West (the US). It was fascinating to imagine these stories happening simultaneously. Imagining Olga in the Gulag at the same time as these innocent Washington typists are getting donuts and fixating on blouses.

I’m obsessed with this idea of how easy it is to just think of our own countries, or only think of their own experiences, and never understand that these other things are going on in the rest of the world. Even the most well-intentioned people tend to come at it from an American perspective instead of thinking about what might be going on in China or Turkey, where writers are being imprisoned for what they’re writing. I’m interested in that duality—living your experience, but also, this giant community of people that have so many different experiences.

There’s a part where Teddy [one of the CIA agents] says, “art can only thrive in a free nation.” What do you think freedom means today? And is it the type of freedom that Teddy would approve?

What Teddy says—that is the ethos of the CIA; that if we live in a democracy, a free democracy, that art will be able to thrive. But even back then it was a false promise. Books were being banned here as well. People would publish under pseudonyms if they wrote anything subversive. [That ethos] wasn’t true then, and I’m not sure it’s true today. I’m not going to be imprisoned for writing something subversive. But in other countries, I would.

There are other things that limit our freedom.

I think that under capitalism, there isn’t such a thing as completely free art, because it’s all monetized in some way. And that has an affect as well.

Within the pre-Langley office where you situate your CIA plotline, you also depict how homosexuality was seen as politically subversive. So even as the Americans celebrate their more expansive freedoms, they don’t see the suppression they create within their own establishment

It’s almost the same kind of duality as before: terrible things happening in other parts of the world, but at the same time, things are ramping up here. Freedoms are being taken away by people just to live their lives. How can art survive in a society like that? Sometimes art is created in the midst of suppression, as Boris Pasternak did with Doctor Zhivago.

What made the Soviet government perceive Doctor Zhivago as such a serious threat?

It was critical of the October Revolution in a way that was a little more subtle than you would think. If you read the book, you’ll find it is more about the individual’s experiences after the revolution—not necessarily even saying that it was a bad thing. In fact, some characters think it was a great thing, or that it was a great for a time. The honest portrayal of individuals was what was so subversive.

The articulation of singular voices rather than the collective?

Pasternak balked at collective thought. His people have such different experiences. It’s a Russian novel, so there a hundred different characters, some of them thriving under the rule while others lose everything. He gave us all these different pictures, including characters like Yuri himself. So not just falling into groupthink as the best course of action: that was subversive. It also went against the norms of what other people were writing, in terms of socialist realism.

Today, it’s very common to read about collusion with Russia. What was it like to write and research a book that expresses a very different type of relationship between the US and what was then the Soviet Union?

When I first started working on the book, Russia wasn’t nearly as much in the news as it is now. But it’s always been a part of the American background. I grew up in the ’80s, when every villain was a Russian, even in Rocky! It’s built into the system. Now, you think that the Cold War has ended, but wow, it really hasn’t ended at all.

Given the different media landscape, how were political views influenced, then versus now?

In the 1950s, books were upheld as the single most powerful weapon to change the hearts and minds of citizens. So much so that the CIA had this book program, knowing that Russians at their core are a literary people. In Russia, you see these giant statues of Tolstoy! The CIA knew that books could cause real unrest. Now, I think, instead of books, people are using social media and fake news. Words are still being weaponized. Even more effectively today, because governments know how to target precisely. The quest for power has never ended.

When it came to writing the love story, which Doctor Zhivago is so famous for, what led you to create a queer love story as the American counterpart to Boris and Olga’s affair?

I had always wanted to write a mirroring romance, one that explores the love story of Doctor Zhivago. But what did that love story actually look like? The people that it’s based on, Olga and Boris, what was their love story actually like? In the West, I was always looking to kind of have a mirroring love; another great love story. When I was writing and researching and came across these two characters [Irina and Sally], it was very organic. I thought that they would fall in love with each other. When I was thinking about their first scenes together, mapping out Sally’s training of Irina.

The rebelliousness of their feelings for each other feels like an incredible risk, not unlike Boris and Olga’s.

The Lavender Scare was popping up all over the place, which had never been taught in my American history courses. Many people I spoke to had never heard of the Lavender Scare at all, which coincided with the Red Scare. Everyone knows what the Red Scare is, but the same time, people in the US government were being hunted if they were suspected of being gay or lesbian, or even friends with someone who was. They would be questioned and then fired immediately without any recourse. People would have their names printed in the newspaper, publicly outed against their will, which led to all kinds of terrible consequences. This happened to thousands of people, in practice by the federal government into the ’90s, when Bill Clinton signed a law against it. I was just like, wow, what would it be like to live and work as a person who is falling in love with another woman for the first time? And what would the consequences be?

The novel is full of extremely vivid historical detail. What did your research entail?

My base research was the CIA documents, and I kind of eased myself into the story with Peter Finn and Petra Couvée’s book, The Zhivago Affair, which was a nonfiction retelling of the mission, the factual mission. I went to Russia when I started working on the Eastern side—travelled to Moscow and Peredelkino to see Pasternak’s house and forests and his gravestone, the cemetery where he’s buried. It was really fascinating to get that elemental view of what it would have been like to walk in that village.

What did you reference for the chapters where Olga is in the gulag?

There are a few books, like her own autobiography, A Captive of Time. Her own account of what it was like to have lived through it and gone to the labor camps was really, really helpful along with Anna Pasternak’s nonfiction book, Lara, which came out midway through my writing process. Archival photographs were also really important.

You took a strong investigative approach to writing this novel. Do you feel like you’ve satisfied something, having published it?

I was obsessed with Olga/Lara as a different sort of muse. I wanted to know, what does that mean, to be a muse? My big connection to the story was: who is this person that I was named after? Now, I think I’m ready for something new. The themes that I’m interested in still resonate. I’m very interested in the power of words and propaganda. We’ll see where that goes. With [The Secrets We Kept], I had the historical backbone, but I wasn’t plotting it out. When you’re researching and you find something, you’re like, oh my gosh, this is it! There are characters and this is what they would do. And I think that is so much of the joy of research and writing—it inspires you to go down different pathways and change up what you thought you were going to write about. For me, I have to be completely passionate and completely obsessed with the characters. So even if I have a really good idea, it doesn’t mean anything until I find out who these people are. That’s what I’m trying to do. I like historical research. But even if it’s contemporary, research is a big part of my process.

Seems like it involves a lot of legwork, too.

I like to joke that my next novel is going to be, like, one person in a room.