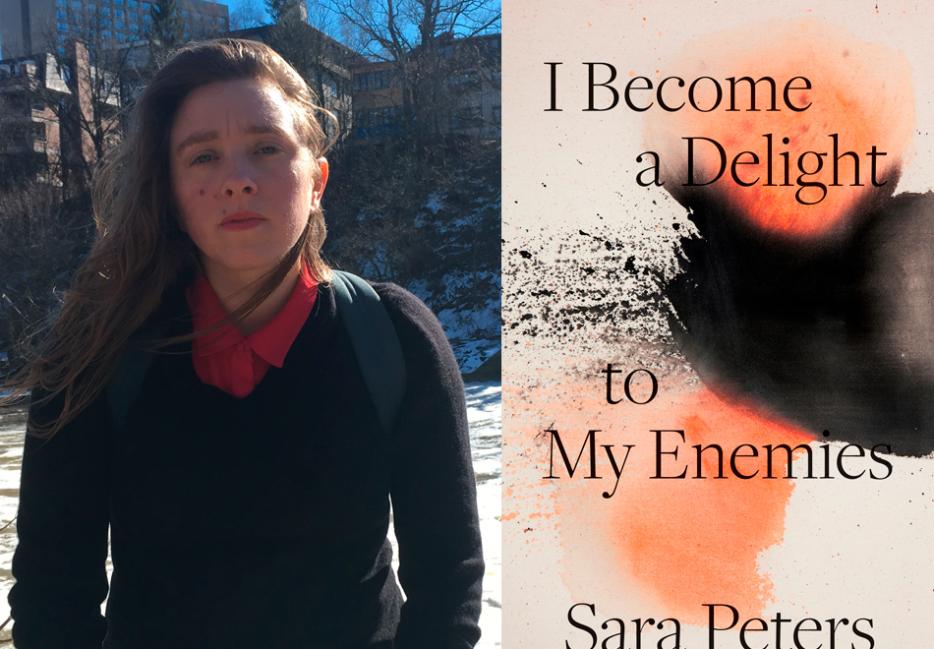

Sara Peters and I began our email correspondence on a beautiful September afternoon. Outside, the birds were frenzied. My neighbour blared electronica. Nancy Pelosi announced a formal impeachment inquiry. It was as if the world was trying to compete with Sara's brilliant, glittering, hilarious, and brutal stampede of a book, I Become a Delight to My Enemies (Strange Light). Well, the world did not stand a chance.

Described as experimental fiction, Peters' novel is the story of a town built upon an underground lake. The town has all of the indicators of civilization: a school, a convenience store, a mayor, discarded wifi networks, marzipan, gold nail polish, factory meat, many hospitals, and a "Farmhouse" for unwanted girls. The story is told by both the living and the dead-a polyphonic choir of female ghosts.

Composed of vignettes, marginalia, and transcription—no page numbers—Enemies is, in the truest sense, its own animal. And yet, this wildness is met head on by Peters' knife-sharp prose, deep humour, and critical intelligence. While I was filled with awe and other darker and more dangerous emotions, I was never without orientation. Our correspondence took on this same quality as we spoke directly and openly about control, loss, shame, and that tricky outfit known as the female human body.

Here is how it began:

Dear Sara,

Please interject "as you wish" (Princess Bride). I'm hoping our correspondence will be pulsing and spontaneous within this old school approach of exchanging telegrams. xx. from my attic studio in an overlarge tracksuit with SAD lamp blazing.

Sara:

This sounds perfect. I've put on track pants in your honour, and I'm covered in cat hair, listening to Pharoah Sanders and fucking with my split ends.

Claudia Dey: This may be an impossible way for us to begin, but I have to tell you that I have never had a reading experience—until Enemies—wherein I wanted to both read the book and consume it. I finally understand why women tattoo Anne Carson passages to their necks and biceps and hipbones with anatomical drawings as backgrounds for her lines. The neurologists say that, in terms of brain response, reading is only second to lived experience. So thank you, Sara, for the deep haunting and cellular rearrangement.

Alright, now here is my question. Can you pinpoint the moment Enemies began for you? Maybe I'm trying to break up its spell into parts? Identify the source? Some writers talk about this moment as an anguish, a possession. For me, it presents the way an infection might. I draw the curtains and sort of take sick with images and voices, and the only way to cure myself is to write them. Can you take us back to the beginnings? How did Enemies take hold of you?

Sara Peters: Hello Claudia!! Thank you so much for this description—I am unbelievably grateful to you for reading my book, even more grateful that you wanted to consume it, that makes me want to scream and joyously break everything in reach.

How it began: I was in Robarts Library at University of Toronto with my dear friend Anastasia (we had made a pact to work together). We sat at one of those eight-foot tables on the first floor, and she vanished industriously into her laptop and I put my head on my folded-up jacket and took an 80-minute nap. When I woke up I remembered reading—or hearing—something about an animal that would run from predators until its hooves wore down to nubs. And I wondered what would happen if that animal kept running, and then I wondered what would happen if that animal were a woman, and then I started to write about it, and I eventually called what I wrote "Hooves." Because the premise was "impossible" (in the piece the speaker "runs" until her body has entirely worn away, except for her head and shoulders) I felt immediately that I wanted to write out of, or about, a different world, and that's how I came to think about the town. I wanted to write a book that felt supernaturally slippery and alive.

I think that was also the (more explicit) beginning of my interest in writing about shame, which I will definitely return to again and again in life, and likely in this conversation!

It's funny: I long for the kind of sickness and possession you describe, but I have never felt it, in my writing. I have never felt that my characters or stories or whatever were anything other than under my control, and sourced in my own mind. I am almost never taken off guard—I want to be! When I hear other writers talk about characters or stories breaking the leash, or doing things they hadn't planned on, morphing in unexpected ways, I am astonished and envious. For me, one of the deep frustrations of writing can be the predictability and scale-ability of my own brain or psyche or whatever you want to call it. I always feel hyper-conscious of my own absolute agency. I am never possessed; I am never transported. I am always the one making the decisions. I am a frequently-bored despot.

I am so curious about your experience of this! Do the images and voices feel immediately in relationship with each other, emotionally and/or atmospherically? Or are they more discrete/closed systems?

O what a beautiful answer. We could swap brains? I could be the yawning despot and you could be the channeler? I would say that yes, for me, the voices and images are in a relationship that slowly makes sense of itself—over time. Together they are the asteroid crashing into the earth and lighting everything up, gorgeously, catastrophically (they signal I will be behind a door for three years). I have very little control until midway through the process when I start to impose systems, markers and so forth, scalpel-edits. Until then, I just try to stay porous and let all my angels and demons into the room. I've tried to plan things out in the past, but find I just ruin everything that way. I want to get to Shame, a woman's meanest, dearest friend, Shame. But first, the town.

The town could, on its welcome sign staked into the ground, have SHAME carved into it with the population beneath? Alright. The town is "slippery." It is quite literally built above an underground lake. Its story is told by its occupants. These occupants are both living and returned from the dead—a choir of ghost voices loosed in the book's opening pages from the northeast cliff. In order to receive the truth, we must hear from all souls, yes? The fragile boundary between worlds—living and dead, land and water—is so unnervingly present throughout the book. I think the title operates perfectly. It is the indirect, clean entry to the book. It sets us up for this flux and instability—you place Delight beside Enemies for starters. Can you tell me about the title? This discarded wifi network?...

I was recently thinking about the wifi networks in response to a (wonderful) question that was posed to me about them. I wanted the title to be extremely specific, yet general; apparently first-person yet untraceable; impossible to absolutely define, perhaps paradoxical, but hopefully rich in particular emotional meanings. To me, wifi network names are fascinating visions into time/place/culture. And I wanted my book's title to be a public secret: someone chose it, but who, and why?

(I am so envious of your description! I want this asteroid crash and everything associated with it to happen to me!)

I think that a huge part of the issue, for me, is that writing has never felt like a "natural" act (whatever that means). I've done it my whole life, but I can't remember a time when I entered into the TASK of it feeling anything less than reluctance, and a slight amount of anger plus despair. I used to feel deeply weird about my sour and twisted relationship with writing; now, I don't care. I am in awe of people who write joyously and/or easily; people to whom it feels necessary, organic. I have decided that I don't need it to feel natural—actually, that I think that's a specious and largely meaningless descriptor.

Do you believe in this idea that—I love its plainness/classic Lucia Berlin to articulate something so big so cleanly—this idea that writing fixes or repairs your life?

I don't think I believe in permanent fixes, and as for repairs... I don't know. I feel that for other people, this could very well be the case—I can imagine writing providing solace, solidity, occasional answers. It feels impossible to speak generally. For me, writing can force clearer articulations of emotional, psychological, philosophical, and political ideas and realities—my own, and what I imagine of other people's.

I think I understand this—a repair has that on-switch feeling of the word miracle, which has always sounded like an ice cream flavour or a stripper name to me. Maybe more along the lines of Ottesa Moshfegh (whom I think is a kind of prose cousin to you; she once described her work as both refined and corporeal—“like seeing Kate Moss take a shit"). She talks about writing as a way to "rise up to a higher realm of existence."

Okay. On the subject of "clearer articulations of... realities"—both your own and other people's... I have a friend who has experienced too many losses in her life. She has started to meet with a woman in a carpeted office, and this woman brings my friend's dead into the room. I pictured you this way—as both the medium and my friend with her losses. I don't want to read into your private life for a second, but I do want to address the many voices of the book. Does this image of the women in the carpeted office make sense to you?

I am a fan of Ottessa Moshfegh! Especially McGlue. (And Lucia Berlin, of course.)

The image of the women in the carpeted office makes immediate sense to me symbolically and also literally (slash factually). The literal/factual part is that I am a therapist (in training), and I've been seeing clients in private practice for about three years. I have also worked with various therapists (as a client) for many years, so I have been, and will continue to be, both women in that room.

The many voices in the book... it's funny, as I think about them right now, in this moment, my mind feels very empty. I would love to say something smart and complex and incisive about the decision to make the book polyvocal: what I hoped to accomplish, what I hoped to resist, etcccccccccc. I had so many reasons and ideas and justifications and aesthetic arguments, and now I can't remember any of them, so I wonder how much they actually mattered to me.

I am thinking about your friend. I always wonder about people experiencing profound loss and grief, and how best to support them, therapeutically. How to try to be with them in their agony, without... making assumptions about how they feel, or what they need. Or (internally) comparing their stories too much to my own, in an attempt to find a shared landscape. I can personally imagine feeling very resistant to a therapist-stranger doing any sort of conjuring around my own dead; my reflexive impulse would be to say: Don't touch this, you didn't know them, you can't know them. Don't fake it, and perhaps don't even try.

Regarding conjuring... I think your book achieves this delicate and profound effect of resurrecting ghosts without laying claim to them... I want to move on to the female human body. You write the mad and unwanted girls who are sent to the "Farmhouse." The Farmhouse is lorded over by the Chancellor in his throne, rubbing softening cream into his hands. A thousand rapes and murders came into my mind as I read about the Farmhouse. Robert Pickton, Marc Lepine—though the book is far from a victimology. In "Third State," you write:

We no longer felt tethered to human vanities: we played host to all manner of insects and parasites. Being female, we had been taught to wonder when we would break off into factions and assemble against each other. We waited for the lies and betrayals to begin, and when they did not we knew that, in this way, we had defeated the gunman.

You write the stories of twins, the result of incest; a six-fingered woman who saves a drowning boy, teaches the piano and weeps without apparent provocation; teenagers in the fluorescent night light of a convenience store in complicated bras, under transparent umbrellas, looking for shelter; a teacher whose pants are too tight—she is allergic to chalk, and ages at hyperspeed like a face in a horror film. You write "Hooves"—the dream that started the book wherein a woman is worn down to her face and shoulder blades as she transits the earth, picking up cigarette butts, running into hydro poles etc. You get the humiliations and the glories of the female human body. The female body that can multiply and produce other bodies. The female body that can be saviour, oracle, prey to male violence. This is our moment to come back to shame. Why do you revisit shame in your work?

I revisit shame because I think it is the most nefarious and contagious emotion; the most isolating; the most linked to self-hatred, the most linked to a sense of being contaminated, disgusting, stupid, alone, apart. And, obviously, it can so often become lodged in us after experiences with abusive people (as in: sexual assault, physical violence, emotional abuse) and abusive systems of power (white supremacy, colonialism, misogyny, transphobia, to list only a few).

I have felt an enormous amount of shame, in my life. It was a corrosive force within me for many years. But I don't want to speak entirely in past tense: of course I am not shame-free, of course I never will be! I write about shame because:

1. It is the emotion that most of us would do almost anything to avoid feeling.

2. Most people hate talking about it.

3. For me, it is very difficult to write about.

4. It exerts tremendous power, often invisibly.

5. It is closely linked with control.

6. it is closely linked with privacy, and exposure.

7. It lies to people and it kills people. And its lies limit our lives, and make us feel unworthy of love, care, empathy, and connection.

I just felt profound relief that your writing about shame in this interview will be published on the internet. This is an example of when writing can function as an empathy machine. Thank you, Sara.

There were times, as I was reading, when I wondered if you had a kind of hazmat suit to protect your being as you wrote-because you scrape up against everything that hurts. But I want to pivot here. Really pivot. To my surprise and delight, Enemies is often deeply and unnervingly funny. I want to talk about funny. An aside I guess: my feeling about the dominant culture is that it doesn't find it easy to acknowledge that women artists are funny. More important, this book, this book—the emotional and bodily gore of this book—Enemies makes Blue Velvet look like a pastoral—this book is so immediately and naturally funny. The funny is never manufactured, never inserted. Here's my question: what is your relationship to funny? Your need for funny? Is it a kind of salvation or oxygen?

I would love a hazmat suit, but for fashion!!

I'm thrilled that you found the book funny, and that the humour didn't feel manufactured or inserted. Humour is so important to me, personally and aesthetically. It feels crucial as a balm and a balancer, and also as a way to take myself and ***MY WRITING*** less seriously. Or, rather, I want to take both of those "things"‚the me-thing and the writing-thing—extremely seriously, and not seriously, at all. I wanted the book to feel emotionally prismatic, and I also wanted to talk about trauma and shame in ways that felt accessible, immediate, and real. And, for me, there is great freedom and release and defiance in finding ways to laugh-genuinely-about the most devastating aspects of my life.

And oh god, yes, the whole women-can't-be-funny thing. It is so culturally present, as you note. And so wildly, contemptibly stupid.