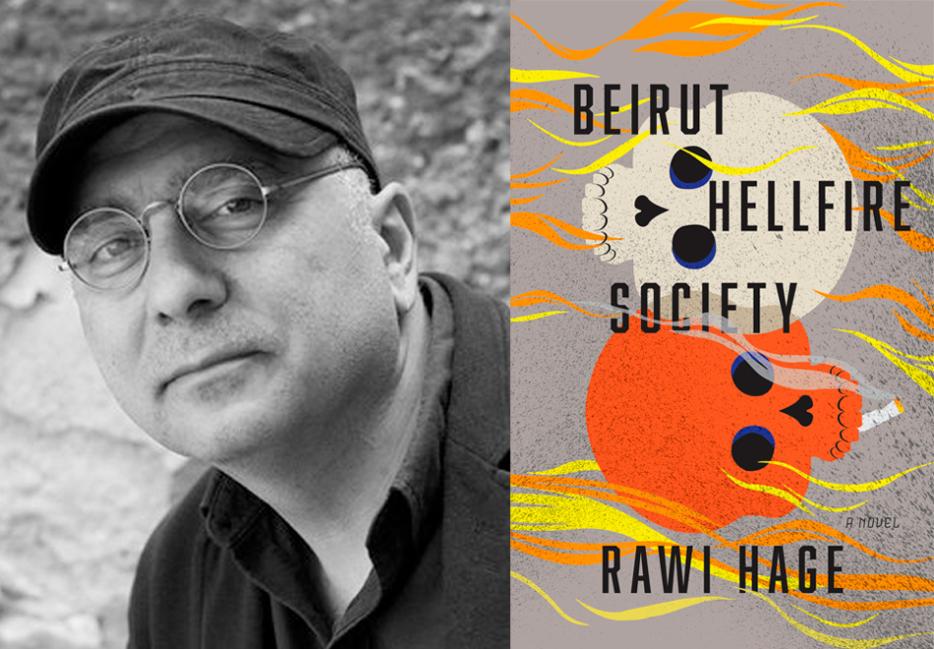

Rawi Hage’s Beirut Hellfire Society (Knopf Canada) is a delirious percolation of grief and remembrance. The novel takes place in Beirut in 1978 —just as the Lebanese Civil War began to crescendo—where Pavlov inherits his father’s task to cremate the bodies of the unknown, the outliers, and the shunned. Pavlov’s undertaking of burial also serves as his induction to the eponymous secret society, which operates on the fringes of conflict while full of flashy, hedonistic characters. What you get is a story that is not only critical of nationalism and religious superiority, but one that is lush with fabulism and decay.

Writing about war is a dance between respecting the integrity of collective memory and finding the freedom to revisit it in fiction. It’s a dance that’s all-too-familiar for Rawi Hage, a survivor of the Lebanese Civil War who came into recognition via his debut, De Niro’s Game, which chronicles the friendship between two men as they struggle to survive in the same turmoil-ridden landscape. The novel won him the International Dublin Literary Award. More than a decade later, with Beirut Hellfire Society, Hage circles back to writing about the civil war.

Amanda Ghazale Aziz: What stirred a return to writing about the civil war? Why now?

Rawi Hage: I was trying to write a book about death, about loss. I was thinking about situating it inside Sarajevo at one point because I was there a few years ago, but then I felt that Beirut is more familiar and the Lebanese Civil War would surely provide that amount of death, especially that excess of death. I found myself going back without any hesitation.

Let’s consider the act of burial in this book; Pavlov’s newly acquired task to bury the outliers of society reminded me of the collective conscious affected by the missing and unclaimed bodies (Tel al-Za’atar, for instance). I have to say, writing about burial of the unclaimed and shunned seems like a partaking of the ritual itself.

Well, I started this book as a personal mourning for friends and family and close people, and the Middle East in general, with the amount of cadavers these wars were and are producing in various regions. That access of a parade of cadavers. The book is a bit fantastical, it’s a bit unrealistic, but that was made on purpose. I think we’re ready, as Arabs, to move on with how we process these events, much like in Latin American literature and magic realism.

The fabulism in Beirut Hellfire Society is a way of processing?

Yes, and it’s also a way to contribute to a new form of Arabic literature. I think it’s due. I’m not the only one, and I think it’s time to move on from that nationalistic literature and head into that of the imaginary. I think we’re ready. Especially with the new generation. If anything, I’m writing for the new generation and hope that they would carry this on someday. I think, by seeing the new generation [of Arab writers] doing amazing things—they’re very combative in that sense—that I get my inspiration from them. I don’t get it from my generation. I hope I get to play a role of transition.

You were formally trained and worked as a photographer before you ventured into writing. How does memory and documentation guide you as a writer?

I think when you experience a certain trauma, the only way to see the narrative clear is through images. I think it’s a phenomena for people who went through wars, it’s a mechanism of coping with the trauma. Maybe I’m projecting, but maybe that’s my experience. When I recall the war, I recall it in images, not verbally or by text. That’s what really comes to me: fragmented images, much like photographs. Images in different sizes that can be interpreted or projected on or be used as a memory to recall events. At least that’s for me. I think the system of recollection, which are in the form of images to me, is much more current for people who experience collective trauma.

Collective trauma and memory has me thinking of Etel Adnan’s question in Night: “Is memory produced by us or is it us?” When it comes to collective memory of wartime and location, though, what do writers owe to readers and the event itself? Do they owe it to collective memory or do they serve the story first?

There are many functions, but I’m not sure with literature to what extent it contributes. It depends on the era, too. I think in terms of severe crisis, many literary writers try to become a spokesperson or try to record things as close to reality as possible. I know for the Lebanese Civil War, after it had ended, the government had tried to obstruct the memory as much as possible. It was a conscious decision to not talk about the war, or to excavate what happened. It was only done by artists, such as Akram Zaatari—there was a small group who were very conscious about immediately recording the war. What was interesting is they recorded in a fictitious way. If you look at their work, it’s very close to fiction, and that’s maybe because the narrative of the war was still contested. There is no official say, but certainly it’s still contested, though I think most of the artists were sympathetic to the left-leaning narrative of what happened, which I agree with. You know, it’s a very tricky balance. You don’t want to write with an agenda, as it affects the art, but you don’t want your art devoid of history. So it’s a very, very fine balance. When I had set to write De Niro’s Game, my intention was to write a book of literature and to contribute to the literary scene. Having said that, what concerned me the most was the trauma that I couldn’t escape. I think with this new book, I’m moving to somewhere different. There’s been enough recording of what has happened by other artists; the Arab world, they’re outspoken… There are six-hour arguments. Things are out in the open, the politeness is not there.

I agree. I also think there is a burden for racialized writers to represent the whole community, to have the last word on a said event, which is impossible.

That’s right. The responsibility, the burden, is much heavier for us. If we don’t exercise our collective imagination—and not just documentation —we’ll always be at a certain disadvantage. I think what literature could provide us with is showing other possibilities. What I fear most is homogeneity.

Ancient Greek literature is heavily referenced in Beirut Hellfire Society, with Pavlov’s obsession with the Iliad in particular, what with the downfall of Troy serving as a mirror to that of Beirut. Were you reading any works of Ancient Greek literature during your time spent writing this novel?

Yes, I’ve read the Iliad many times—it’s a book I’ve read again and again. I like it, I like the poetry, I like the story, but I also like the Greeks in general, though I do not want to idealize them. They were like any other empire: oppressive. What I like about the Greeks was the multiplicity of gods and goddesses, and how accessible the gods were, and that transformation between humans and gods. That accessibility. Gods were not unanimous, and the Greeks knew it, they were very conscious that they had constructed their own gods. I like that, I think that it’s much more sophisticated, especially with how open they were about the failures of their gods.

The Greek deities were notorious for being as jealous and selfish as humans, if not more.

So selfish, so openly manipulative that it’s hard to take them seriously! They’re so transparent that they’re a mirror to their own society. It’s almost naive. I don’t know why I like reading these works, but it certainly helped my writing. There’s a certain courage that I appreciate.