I’m the only man in the village who subscribes to The Hollywood Reporter. The latest clipping, which I paste in my scrapbook, is just a column inch, an ad for waterbeds on the reverse.

Black Water director Edgar Van Buren is once again facing criticism, this time for his decision to host a lavish party for the jurors who acquitted him of manslaughter. Held at the director’s mid-century home above Coldwater Canyon, the party marked the one-year anniversary of the verdict, on May 15, 1988. All twelve jurors attended. The father and former manager of Doretta Howell, who intends to sue for wrongful death, has called the party “proof you can’t find one good man in Hollywood.”

I recognize the byline. The writer had tried contacting me countless times throughout the trial, but I could not be reached for comment. Because I was non-creative personnel—below-the-line, as they say—and had no height from which to fall, I could avoid the most public disgrace.

But behind tinted glass, the studios don’t forget. Without the help of the courts, they took everything from me, my whole life in America. And I can’t imagine where I’d be, if they knew my version of what happened.

*

After a morning of being thrown through a window, Dot Howell collapsed in the honeywagon, unable to proceed with her French. I remember handing her a Yoohoo and picking sugared glass from her hair. Edgar Van Buren insisted his actors perform the stunts themselves—no body doubles—and as I testified, she obeyed his every direction.

Dot and I wouldn’t get our three hours that day. On the set of The Chasm, our lessons were just ten-minute fragments before she was hauled off again. The few times I cornered a producer—and once, disastrously, Van Buren—he wouldn’t take me seriously. I said Dot needed those hours, there on the shag rug of the honeywagon, chewing Skittles and microwaving in the desert heat. I said she needed to be a girl for three hours a day.

I asked her, “Do you think he got the shot?”

She shook her head, a shimmer of glass.

All she could focus on was the model. A Medieval French castle surrounded by the sodden country of my native Normandy—it was our class project; we had a different one on every shoot. Now Dot cracked the lid on another tub of clay and slapped some on the hillside. I didn’t protest, but lately the clay had been piling higher and higher, while the castle went unfinished. It wasn’t encouraging that she pictured Normandy as a muddy wasteland.

“Soon we’ll need to add the servants’ homes,” I said, in French.

Dot massaged a lump into the landscape.

Finally, she said, “I need to tell you something.”

I kept picking at her hair.

“Stop it,” she said, freezing my hand.

Dot had never addressed me so formally. I sat very upright behind my desk and put my fingers together in a steeple, as if to show her that when you speak like an adult, everyone around you grows cold and severe.

“Dad and I made an agreement,” she said. “When he gets here, he’s going to be my manager.”

Betraying nothing, I said, “He was supposed to be here yesterday.”

“I know that.”

Dot’s first assistant pounded on the honeywagon door. It was time to go back through the window.

“Do you think he’ll come today?” I asked.

"Probably, yeah."

“That’s not very professional.”

Dot looked at her dirty hands, and suddenly lurched at me like a beautiful, filthy little vampire.

I neither flinched nor smiled.

*

God hated The Chasm. If I believed in predestination, I’d observe how He arranged the production’s calamities to torment Edgar Van Buren. The director’s perfectionism was the stuff of renown—dozens, sometimes hundreds of imperceptibly different takes to achieve the one. That’s why, despite everything—despite the drinking, the verbal abuse, the reckless endangerment—everyone wanted to work with him. It was a chance to be a part of something everlasting.

Yet on that project, everything conspired against him. Twice the set was ripped away by sandstorms that gathered on the radar, blood-red and too late to evade. That’s when Dot and I laid the foundation of the castle, the honeywagon rocking in gale-force winds. And we had further opportunities to work when the elder star, Xavier Braun, stepped on a rattler and was bitten three times, fast as automatic weaponry, and had to be air-lifted back to Los Angeles.

The Chasm was Van Buren’s first horror film. Having asserted himself in almost every other genre—comedy, history, war—it was an aesthetic challenge he’d set himself. But what was it about? The script was impressionistic, constantly reappearing on different-coloured paper as it underwent another visionary mutation. I don’t think he really understood what horror meant—not yet.

In the latest version—mustard yellow—a narrative spine had formed at last. A runaway orphan (Dot) hitchhikes into the desert, and comes upon a seemingly abandoned chapel, only to discover a man (Braun) living inside. The orphan mistakes him for a priest, but as it turns out, he’s an escaped convict, a child-murderer. The title, as I gleaned from the mustard-yellow version, referred to the psychic underworld into which the killer initiates the orphan. But everything else remained indistinct. The budget was ballooning. The studio was terrified.

Van Buren’s indulgent, improvisational method was a Hollywood anachronism. He’d inked a famous contract in the late 1960s, wedding him to the studio in perpetuity, but guaranteeing certain artistic protections. At the time, it had seemed like a colossal mistake. But by the ‘80s, he was the last of his generation’s directors still to be provided unlimited budgets and vast creative leniency. As his fellow auteurs found themselves directing second units on third sequels, Van Buren remained untouchable. He took as long as he liked; the budget was just an abstract figure to him. At night, he’d start a bonfire and drink to semi-prophetic excess, sweat shining in the flames, and everyone waited to hear what he’d discovered and transform it into cinema.

I didn’t care about Edgar Van Buren or his Chasm. I was there for Dot, Dot alone. I only dreaded the one calamity: that Ryder, her father, was coming to take over her career. And what would that mean for us?

*

It was dusk when Dot’s bike finally skidded to a stop outside the honeywagon. After a Yoohoo, to my amazement, she took up her math textbook and moved through the algebra with vigour, as if her mind were ravenous. In our classroom, all was orderly and French and still as a mirror. In fact, it was I who spoiled the environment.

“Is there anything I can say to persuade you?”

Not looking up, she said, “No, Pascal.”

“He’s a day late. He doesn’t call. Is this the behaviour of a manager?”

She placed the pencil by the page.

“You don’t know him.”

Something in her voice frightened me, a kind of echo from a place I didn’t understand. I corrected her pronunciation and poured some Skittles on her desk. She exaggerated the sticky gnashing of her teeth—that was better.

And then I heard the crunch of tires, and we were outside, headlights sweeping over us. As the truck rolled to a stop, it nearly mangled Dot’s bike.

Ryder slammed the door of the Ford F-series, which she’d bought for him. He was bald, but wore a red beard, dense as a forest observed from a jet, and his barbell biceps were unevenly patchy, the hairs like scratches. Already he looked northern and overheated.

“Doretta!”

He could barely support her when she leapt into his arms.

“This is Pascal.”

We shook hands.

“You’re the teacher.”

Dot cleaved to me and said, “Mon astre.”

“What’s that.”

I felt a warmth in my cheeks.

“There’s no good translation,” I said.

“I’ve told you about him.”

“Sure,” he said, “I remember.”

“And she’s told me about you,” I said.

“Alright.”

Ryder told her to look at the sky. Wasn’t it indigo? Wasn’t it beautiful?

“It’s like that every night,” said Dot.

“Is that your bike?”

“Yeah.”

“Good for you. Remember where I taught you to ride?”

“Lake Erie.”

Ryder glanced at me.

“I found a little spot with a view of the valley,” he said. “Get in the truck. We’ll catch the last of the light.”

The sky was fading fast, but Dot humoured him. He heaved the bike into the cargo bed, and in another moment, the truck veered away.

I replaced the textbook on the shelf, and dropped her pencil in the oblong ceramic cup we’d fired together. Then I corrected her algebra—so many mistakes—and my day’s purpose was fulfilled.

*

Awake on the honeywagon’s narrow bed, I listened for that shy knock on the door. Then she’d come inside, as she’d done so many times, and wordlessly curl up on the carpet. I’d imagine her sucking her thumb as we fell into our dreams.

No one ever appreciated what those children went through, not until something happened—and then everyone had an opinion. But they were a lot like a movie set, like the chapel they’d built for The Chasm: pristine from certain angles, behind which the trash collected and a producer was smoking.

Eight years old, Dot had been given to me on a set at Nickelodeon. I mean that in earnest: her mother, Roxane, just a bruised little child herself, entrusted Dot to me. After a brief, impulsive marriage to Ryder, Roxane had fled to Los Angeles with some inarticulate ambition, but before she even had headshots, she was drinking for breakfast and coughing.

The limelight isn’t morbid; it skipped over Roxane and fixed on her daughter—Doretta “Dot” Howell of the rosebud hair, the endless eyes. Doctors said they were actually growing too big for her head. With that monumental face, Dot appeared like an adult you’d once known, or had, at least, once seen on screen.

Those are my fondest memories, still glowing. I recall Dot as an energetic blur. At Nickelodeon, we’d play hide-and-go-seek, and she’d give herself away with laughter. She’d do anything for Skittles; she’d imitate the sound of French. When the Enquirer started following Roxane around, just to catch her drunk in public, Dot began staying overnight.

After Roxane’s death, I gave up my other children and wholly devoted myself to Dot. I banished the charlatans and money-lenders. I gave her an idea of God, telling her there was always a beautiful man watching her. And so, I was the one she asked about the bleeding; I was the one who told her what it meant.

As for Ryder, on certain melancholy nights I’d hear about him. She had so few memories, she always returned to the one good summer on Lake Erie, stretching it out until it seemed like a marvellous history. When he took her on his back, she said, she didn’t fear the water. The way she spoke of Lake Erie, I sometimes felt she was still waiting for him to take her back and finish those lessons.

Meanwhile Nickelodeon became Disney, and Disney became Fox. And then the Chasm script arrived, on fresh white paper. It was the first script she wouldn’t let me read until she’d finished. From the very beginning, she was doing this for an idea of herself. Now fifteen years old, it was time to choose: orient yourself toward Oscars, or be an unserious girl forever.

The Chasm set was unlike any I’d ever been on. They weren’t creating this movie to be happy, or to make others happy. Lying awake that night in the honeywagon, I heard the crew’s drunken laughter, the hiss of someone pissing on the sand. And Dot didn’t come. I said a prayer for her, alone in the night. She was still so unknown to herself.

*

Van Buren suddenly took Xavier Braun and a small unit up into the mountain caves. They were gone for days, but Dot and I still didn’t get much done. Ryder would scoop her up after breakfast and shoot through the desert toward the cliffs or the Indian reserve. They’d fire off guns together, blowing up the Joshua trees, or skid around on ATVs with a recklessness I’d begun to see as common to them. By the time she got back, she was more depleted, more useless to me, than after the most violent Van Buren workdays.

Yet nothing was so contemptible as what Ryder asked me as I filled my flask at the water station.

“Pascal,” he said, “what exactly do you teach my daughter?”

He’d accosted me outside the shade, the white sun hovering, a pitiless disc, above his head.

I said, “A standard Californian curriculum.”

“And more besides.”

“Well, of course. The state mandates that studio teachers be certified welfare workers. I manage Dot’s well-being, whether it be getting her inoculated, or discussing the morals of the script, or just keeping her company—being there for her, you understand.”

“I don’t want to offend you,” he said, “but Doretta seems, sometimes, a little stunted.”

“Stunted.”

“Basic things—things she should know—she doesn’t.”

“And you’re to judge what she should know.”

“The names of presidents, yes. The cause of the Civil War. All fifty states.”

“American things.”

“It isn’t only American,” Ryder said. “She’s slow with simple math. She knows nothing about tectonic plates, or how tornadoes form.”

“I assure you, Mr. Howell, Dot’s developing perfectly well.”

“Then why can’t she take the proficiency exam.”

I’d been in Hollywood long enough to get guarded when a parent mentioned the exam. The fact that he even knew about it already betrayed him. If an underage actor could test out of high school, she became eligible to work longer hours, overtime, even through the night. A sick green glow always emanated from the heart of a Hollywood parent.

“You’d better leave that up to me,” I said, and began to walk away.

He put a hand to my chest.

“All the same,” he said, “I’d like to sit in tomorrow afternoon.”

“I don’t think that’s a good idea.”

“I’m her manager,” he said, “I have the right.”

He’d kept me there just long enough for my nose and cheeks to burn.

*

Dot was dabbing pink paint on the little princess when he entered. She dropped her brush and Ryder sat, ridiculously huge, in one of her chairs.

In French, I said, “Your father is going to spend the remaining time with us.”

And Dot answered, in American English, “I know.”

I clucked and reminded her to sustain the French, as we’d agreed.

“But it isn’t fair. He won’t understand what we’re saying.”

“As you wish,” and I looked to Ryder. “But you see, there was something being taught here, and now, no longer.”

“Noted.”

I didn’t dare give her Skittles. I handed her the math textbook, and told her to work on the algebra. At first she was confused, thinking she’d seen the problems before, but then she settled in.

As I stared at Ryder, I gradually perceived that he was struggling with the conditions in the honeywagon. Everyone thinks they understand what it means to work on a movie. It was pushing a hundred; the walls were sweating. The toilet was close, unclean. Soon he was fidgeting. I’d applied cold cream to my face, and could sit there for hours, deriving austere pleasures from how Dot gripped the pencil, how she turned it idly in her fingers and nibbled the edge.

I only broke my pose upon hearing the commotion outside. For days, the set had been held in a kind of scorched suspense, but now there were shouts and laughter, cars swooping through camp, refreshingly. Van Buren had returned from the mountains.

Ryder seized upon my distraction to shoot a spitball at his child.

“Hey!”

I turned to see Dot clutching her ear, Ryder laughing like an ape.

She balled up a page from her notebook and rang it off his dome. Now he was looking at her with appetite, and in one brute motion, he cleared the desk away and grabbed her at the waist. She let him pull her to the carpet, laughter breaking into hiccups. I moved the castle to safety and watched them roll around.

Ryder caught my eye, and he must’ve read my satisfaction there. He disentangled from her and righted the chairs.

He said, “I don’t know what came over me.”

Dot was still heaving on the floor, hair strewn over her face. She blew it off her lips and said, “It’s fun here, isn’t it?”

I said, “Isn’t it?”

“Get back to work,” he ordered. “Start working, Doretta.”

*

Ryder befriended Van Buren. At night, I’d see them, crackling bronze figures by the bonfire. They’d pass the Jim Beam, and when it was empty, set the bottle out in the clear moonlight and blow it to smithereens.

Van Buren had come back changed by the caves. He said The Chasm cohered for him there; he was throwing out most of what he had. In the day, producers waited anxiously outside the tent while Van Buren rewrote the script, ash dropping into his chest hair. They called the studio; they tried to explain what he was doing. At day’s end, he’d have the latest scene copied, and issue it like law.

Drunk in that infernal light, he and Ryder unfolded Dot Howell’s future. If she got The Chasm right, there would be more projects, all the awards, unimaginable money. I could hear them howl together—“Yes, yes,” went her father, her manager—and more gunshots.

*

I found the pink pages on my desk. She’d left them for me. I took them out to the plastic chair beneath the parasol with a view of the hills. They were just piles of Martian-red rocks, as if a giant had ground up mountains in his fist. As the sun set behind a dusty film, the sky purpled and dimmed.

At once, I saw why she’d left the new script, why she didn’t want to face me as I read it. The Chasm was darkening; it was becoming real horror. Before, the relation between Dot and Xavier was all innuendo, arresting suggestions between cuts, but Van Buren had made it explicit. So this was what you learned in caves; so this was genius—the molestation of a child on film.

When the night had gathered around the camp, I went looking for him. There was no one by the bonfire, but I heard the pop, the breaking glass, and followed them out to where Van Buren and Ryder were shooting. The light of the moon was so pure, the men seemed to stand on stage, the sand flat and crossed by the shadows of the Joshua trees. Off to the side, three women sat on lawn chairs, smoking in fur coats, their legs bare and blue. They noticed me first, and their silence alerted the men.

I stood with the pages, observed by Van Buren. Behind him, Ryder reloaded.

I said, “You have a wicked heart.”

Ryder hooted, plunking in the bullets.

“What did you say?” and the director stepped forward, close enough that I could toss the script against his chest. He caught the wad, glanced over it, and threw it aside.

“I said there’s a worm in your soul.”

All the while he was coming toward me.

“What do you know,” he said. “What could you possibly know.”

“Ease up,” called Ryder. “It’s only the teacher.”

“I know she won’t do the scene,” I said.

“But she will.”

“I won’t let her.”

Van Buren shoved me with both hands, and stumbling back, I tripped on bramble and landed hard. He sent me back down as I tried to scramble up. I felt his drunk, elemental strength.

I managed to say, “I’m not afraid of you.”

“You’re a fool, Pascal.”

Now he crouched down and slapped me, once. I briefly saw the women, and then my cheek was to the sand. I thought of snakes and scorpions.

“You’re a fool.”

The shots rang out in rapid succession—a woman yelped—and Van Buren stepped back.

“Enough,” said Ryder.

Dot’s father hoisted me to my feet, and brushed me off, motioning for Van Buren to stay where he was.

“Why don’t you go to sleep, Pascal.”

I was staring at Van Buren, his eyes full of moonlight.

“She won’t do it,” I said, to myself.

*

I couldn’t find Dot in the morning, and everyone had a different answer. They sent me to makeup; they might’ve seen her with the first-assistant; she’d just biked by—see the tracks? Finally, I approached the chapel, where they were setting up the scene, and over a producer’s shoulder, I saw her.

“Dot!”

He cut my angle off.

“You can’t keep me out. I’ll have this whole thing shut down. Dot!”

I snagged her eye, and she said to let me through. The chapel smelled of fresh sawdust, but was staged to signal years of decay: a collapsed wall, the Virgin caked with grime, doves in the rafters prodded by the handler on a ladder. And Dot—her dress was bloodied and torn, blotched with black fingerprints and sticking with sweat.

“You don’t have to do this scene.”

“Pascal—”

“I know we haven’t talked about it.”

“We don’t have to.”

“Can’t you see what they’re doing?”

Van Buren was riding the camera like a dark horse, and Ryder stood nearby, reading the pink version. How could he let the scene play out in his mind?

“Don’t let them do this, Dot.”

She seemed confused by how I took her hand.

Van Buren tapped her on the shoulder, and without even looking at me, said, “Let me explain this to you.”

Actor and director angled away.

I got as close as I could to the scene. It was just a squalid mattress by the altar. Dot sprawled as if drugged, eyelids thick and heavy as a toad’s. Her legs were bare, bruised. I’d never seen her thighs, and I remember wondering, absurdly, where she learned to have thighs like those.

Van Buren called for action, and Xavier squatted down. He was strangely clean, grey hair wet, pulled back. The beads dangled from his neck like grapes. It wasn’t artifice—it was lust. It was real in his eyes, and on his fingers, and blazing through his lips. Van Buren thrust the camera forward. I heard them murmuring. Xavier pinned her by the wrists, and she writhed—not against his strength, but within it. He cupped her chin—her soft cheeks bunching, lips squeezed into a square—and leaned into a suctioning kiss. Her eyes closed voluptuously, horrifically. Then she put his hand to her breast and pulled him back onto the bed.

Suddenly Dot sat up straight and shook her head.

My heart thrilled. Van Buren yelled cut.

The director wiped his mouth. Someone brought Xavier a cigarette, and the actors lounged there on their elbows. Van Buren crouched down to Dot and called for Ryder. The four of them had a quick conversation.

Ryder came back to me through the crew.

He said, “She can’t do the scene.”

“I can see that.”

“She’s asking you to leave.”

Doves shuddered on the roofbeams.

“What.”

“She can’t do the scene in front of you. Will you go back to the classroom, and wait for her there?”

I looked to Dot. She put her eyes everywhere else. From a distance, Van Buren was watching me.

“Let me talk to her.”

“You’re wasting everyone’s time, Pascal. Now she’s asked you nicely—go.”

*

I’ll never know if she came back to the honeywagon afterward. I’d taken the bottle to the hills. My sister sometimes sent me Calvados from home, though I almost never found occasion to drink. I’d been working through this bottle for a year, but that evening, I sucked it worshipfully, as if it were the very pith of Normandy.

The desert stars came out, and my mind turned to Roxane. I wanted to pray to her, but the stars were cold, withdrawn. I knew I’d disappointed her. She’d urged me to take her daughter; shaking, she’d pressed the beads into my hand. It was a promise, soul to soul.

And the old picture came, man and wife on a little plot of Normandy. He’s reading in the shade, apples dropping from the tree, the castle in the distance, tall. The children sprint past and she calls to them, still a child in her heart.

But I found no direction there. The picture hovered in two dimensions. The Calvados tasted thin, even putrid at the edges.

Instead a story Roxane once told, chasing Stoli with milk, invaded me. Ryder would have her smear lipstick on his erection, she said, as if his penis were a cheap whore, and then she’d suck it like a woman’s lips. And I thought of the women, naked under fur coats, and I thought of all the money Ryder had now, Dot’s money.

I broke the bottle on the stone, and the liquor burst over my hand. I knew where he slept. The jagged edge of glass caught moonlight, and I felt like Roxane, way out on some private rampage, pursued by journalists. But I didn’t realize how drunk I was until I stood and moved unsteadily, rock by rock, down the hill, and then all I wanted was to be buried underground, asleep.

*

I grew formal over the coming days. I’d taught adults before. No Yoohoos, no Skittles—and where had the castle gone?

Doretta knew I was angry—there were times I thought she sensed the rest—but didn’t attempt a reconciliation. It would’ve been the death of the woman she wanted to be, the icon looming over her, beckoning her out into the world. So it was already written.

She failed at the new lessons I gave her. She had to stay late, do them over. She put on a show of not minding. She tried harder, but still wasn’t ready.

Meanwhile The Chasm was collapsing—that’s something that never made the papers. The producers tried keeping rumour in check, but the studio’s anger was known; it had seeped into the cast and crew like guilt, everyone but Van Buren. He only responded with further provocations.

But in private, as we’d learn during the trial, he was tormented, blocked. The Chasm had no climax. It needed something spectacular—a permanent image—and it was then that water, black and deep and strong as steel cables, began to rush across the desert sands of his imagination.

*

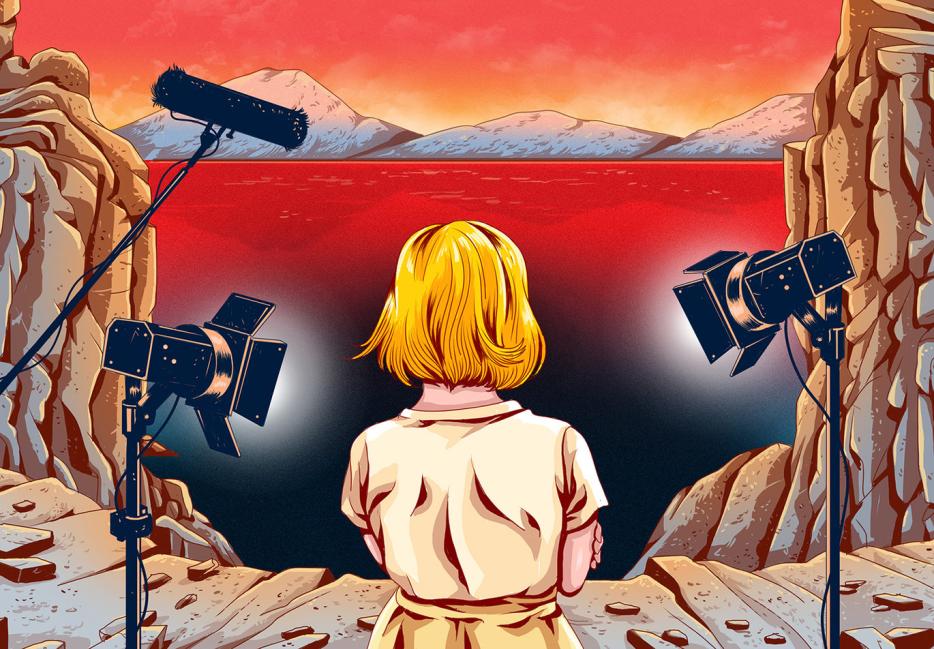

On the morning of the stunt, he had us up before dawn, and announced that we were going to the sea. It was all arranged; he’d sent the crew ahead. Now Doretta, Ryder, Van Buren and I piled into a truck, and headed west, dust blazing up behind the wheels.

I remember Doretta was excited. This was why you worked with Edgar Van Buren—so you could reminisce, later, to The Hollywood Reporter, all about the time he had you up at dawn and took you to the sea because he’d seen the movie ending in a dream.

In the truck he passed around the mint-green pages. Escaping the murderer, the orphan would plunge into the cove. Later, they’d shoot her underwater on a stage at the studio, feeling her way into a cave. But for the drop, the location was perfect, said Van Buren: a little cove of ink-black water.

He said, “A shot of you falling—it could be immortal.”

With the stunt, The Chasm would be whole, at last.

“We shoot at sundown.”

But his star was staring out the window, the stooped desert trees rushing past. In sunglasses, and with a kerchief tied around her head, she looked like a woman twenty years older, twenty years ago.

“What’s the matter,” he said. “Don’t you like it?”

Doretta’s head turned toward me, but she said, “I love it.”

“The audience will know you’ve given them everything,” said the director. “The Academy despises doubles. They want to see you act every frame.”

Only I knew what she was thinking, but I also knew she didn’t want me to speak for her, not anymore. In her shades, I could see myself, just a small man in the corner of the truck, indistinct, like the memory of someone you knew as a child.

*

After weeks in the desert, I relished the breeze that pulled off the sea. All day was spent setting up the stunt, the crew bobbing in lifejackets down in the cove. The water swirled around them, black and deep, like a pit. Doretta would drop from the cove’s rocky wall.

No one ever asked if she could swim.

I wandered away from the set, over to where the sheer cliffs plunged, and stared out to the hovering line of the horizon. Already the sun was lowering and flashing off the water. It wouldn’t be long before the stunt.

I heard: “Pascal.”

It was Ryder. He came to my side and peered into the wind.

“Everything takes forever,” he said. “But I guess you’re used to it.”

“Yes.”

He laughed, “Don’t be so high-strung, Pascal. I come in peace. I know we got off to a bad start, but I’ve been thinking—I was wrong. I mistook her excitement for immaturity.”

“Excitement.”

“For me to be here. She was just being my girl, like before.”

I wanted to say there never was before.

“Shake hands?” he asked.

I’ll never know for certain, but in that moment, I sensed he’d had me fired, that in the morning, I’d be recalled to Los Angeles. Over blinding water, Doretta Howell’s future stretched out to the vanishing point.

We shook. Ryder stepped to the very edge, and looked straight down. The rocks pointed up like bayonets; the current ripped into the open sea. I remember my hands felt light, inspired, primed to push.

But the spirit deflated. He’d prevail, anyway. The bulb inside her had finally split; a powerful stalk had broken through. I saw the mud she’d slung beside our castle. It piled up before my eyes, incompatible with life.

There was a call: “Pascal!”

I turned to see Doretta’s first-assistant, and Ryder and I came running to the makeup truck.

We found Van Buren leaning over the chair where she shivered and gasped for breath.

“What is it,” Ryder asked.

“It just came over her.”

“Give her space,” I said, and knelt. “Breathe easy. You’re safe.”

She’d gone bright red, and hot tears issued from the corners of her eyes, though she wasn’t really crying. I took her hands; the wrists rapidly pulsed.

“You’re safe.”

“We were reviewing the stunt,” said Van Buren. “She’s never been this way before.”

“What is it, Doretta,” asked Ryder.

She was regaining composure, I thought, or a sense of audience.

She said, “It’s nothing.”

“Maybe the water,” the assistant offered.

There was a brief silence while the men decided whether to take her seriously.

“But she can swim,” said Van Buren.

“Of course,” said Ryder. “I taught her myself—you remember, Doretta, on the lake.”

She nodded.

“I remember.”

Later, no one would recall how they all looked to me, even her. But if I forget every other instant of my life, I’ll still remember how I said, “She can swim.”

“Maybe it’s the drop,” said Van Buren. “But the water’s deepest right where you’re landing, and anyway it’s not as high as the window. Alright?”

She touched the tears from her eyes, and pushed out a smile.

“Alright.”

Van Buren clapped. Ryder helped her up.

“I’m sorry to be so childish.”

The first-assistant cooed, “Not at all, darling, not at all.”

Van Buren was out the door. “She’s fine,” he reported to the producer outside.

“I’ll put you on my back,” her father joked.

“Just get me to the set,” Doretta said. “Then I’ll do it on my own.”

*

I remember the light was perfect. From where Ryder and I stood, we could just see her pressed against the wall below, her famous rosebud hair precisely tangled. The cove whirled beneath her, swallowing. The camera lowered to the surface. I heard Van Buren’s call for silence, for action. “Go!” he shouted. “Go!” There was still something I could’ve done. Then Ryder started running, but it was a six-minute climb down to the water. The camera never stopped rolling. The footage was never made public.

*

My sister has set out coffee and Le Monde beneath the apple tree. The fruit is full of worms; a drought has killed her garden. This isn’t what I’d pictured, what I’d tried to make out of the girl once given to me. But I can see the castle, and the indifference of the stone—watching everything, anything—is like the love of God.

In Le Monde, I find another clipping. I will paste it in the scrapbook. There are fewer all the time; soon they’ll vanish altogether. Translated into American English, it reads:

A film by Edgar Van Buren, Black Water, premieres in Paris this week. Critics say the film subtly reworks the tragedy of child actor Doretta Howell, which derailed Van Buren’s last production and nearly cost him his freedom. Black Water has been nominated for Best Picture and Best Director at the Academy Awards, and has grossed over $40 million in the United States.