The story of how Jay McInerney met Raymond Carver reads like a cheesy novel. After college, McInerney lands a job at The New Yorker as a fact checker, but he’s no good at it and the magazine fires him. Unemployed, and with not much to do, he’s hanging out in his lower Manhattan apartment one day when the phone rings. On the line is his old roommate from Williams College, Gary Fisketjon, who’s already making a name for himself as an editor at Knopf. Fisketjon tells McInerney that he and his colleague Gordon Lish just had lunch with Carver. But the two editors have to go back to the office and the not-yet-legendary writer is at loose ends until a reading that night, so the poet and master of the short story needs someone to entertain him for the afternoon. Because Fisketjon is well aware of his fondness for Carver’s work, McInerney assumes the call is a practical joke. But soon he hears a buzz at his door.

At first, the two men—from different socioeconomic backgrounds and different generations—don’t really have much in common. Then McInerney serves some cocaine and the awkwardness melts away as they spend the afternoon talking about books and writers and writing. At 7:30, they suddenly realize they have just half an hour to get all the way uptown to Columbia University. Only a little late, Carver reads “Put Yourself in My Shoes” from his Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? collection. He reads it really, really fast.

After returning to Syracuse, where he’s landed a teaching gig, Carver writes McInerney a letter to say that it occurs to him that perhaps living in New York City might not be that conducive to the young man’s goal of becoming a novelist. He suggests McInerney enroll at Syracuse University and work with him.

And here’s your impossibly happy ending: the two become close, personally and professionally, and Carver writes a blurb for the cover of McInerney’s debut that reads: “A rambunctious, deadly funny novel that goes right for the mark—the human heart.” That 1984 book, Bright Lights, Big City, becomes a massive critical and commercial hit.

*

When a Hazlitt editor asked me if I wanted to interview McInerney, I assumed it was typecasting: an old white male from an upper middle class background to interview an old white male from an upper middle class background. The rationale ultimately wasn’t quite that shallow, though the idea did seem to spring from the notion that “every journalist of a certain age read Bright Lights, Big City.”

He wasn’t wrong. The main character is a fact checker at a publication clearly based on The New Yorker, so obviously every magazine journalist read it. But so did everyone else, or at least everyone who read any literary fiction at all. The novel—which McInerney wrote in six weeks, the same amount of time it took William Faulkner to write As I Lay Dying—was a cultural and literary phenomenon. This was in the days before the Internet helped splinter us into discrete cultural tribes: you could actually go to a party and expect to talk to other people in depth about Bright Lights, Big City.

McInerney was hailed as part of a new literary Brat Pack, a group that also included Bret Easton Ellis, Tama Janowitz, and others. The label had more to do with marketing young writers who wrote about sex and drugs than anything else, but it caught on. I enjoyed Jill Eisenstadt’s From Rockaway, but I gave up halfway through Ellis’s Less Than Zero—I couldn’t stand the novel’s amoral sensibility (or, if that book had a moral compass, I wasn’t smart enough to understand it). And Janowitz’s Slaves of New York remains on my bookshelf, unread for decades. But, since I’m not sure anyone has ever asked me my opinion of it, I never felt any guiltier about not reading that than any of the other books on my shelf that I haven’t read. No, the one you needed an opinion about—and wanted an opinion about—was Bright Lights, Big City. Even my wife was keen that I take this assignment because, she said, “I remember how excited you were to read it back then.”

I reread it before I interviewed McInerney and was delighted that it totally still holds up (unlike much of the cultural output of the 1980s). In just 182 pages, the spare but energetic prose screams along as it documents—famously using second-person narration—the drug-fueled descent of young man whose mother has died, whose model wife has left him and who’s about to lose his coveted magazine job.

All of which really did happen to McInerney. Just like something out of a novel.

*

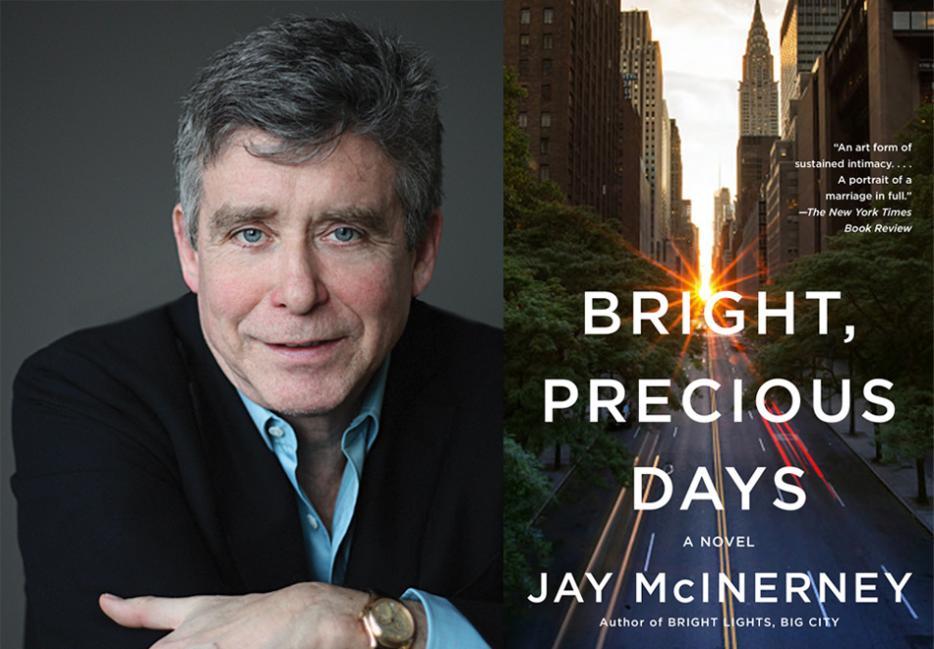

When I met McInerney on a Friday afternoon last October, he was wearing a sports jacket, a light blue shirt without a tie, dark grey jeans and loafers. I found him fidgety: he flicked his fingers a lot and crossed and uncrossed his legs often. He’d been touring his eighth novel, Bright, Precious Days (Knopf), for two months and I’m sure he was getting tired of it. But later, when I listened to the recording, I was surprised at how much he laughed—chuckled, actually—so maybe he wasn’t that bored.

We were in a small meeting room in the Toronto offices of Penguin Random House, not a funky lower Manhattan flat. He was set to do a reading at the International Festival of Authors that evening. We did not snort cocaine. But we did talk about books, writers and writing. And British sports cars.

I’d opened our conversation by asking if a friend of his had smashed his Austin Healey. He laughed nervously, said no and, I’m sure, wondered what kind of psycho I was. I pointed out that an Austin Healey gets demolished in both Bright Lights, Big City and Bright, Precious Days. "Does it?” he said. “Oh, wow, you're right. I didn't realize that until just now.”

And then, a memory: he told me the story of the time his father wrecked an MG. McInerney lived in Vancouver from Grade 4 to Grade 8 and on Saturdays, his father would take him out in the sports car to do errands. One day, McInerney was playing with friends and his father went without him and wrapped the MG around a telephone pole. The passenger side was obliterated. “If I had been in the car that day, I would no longer be here."

McInerney’s first car was an Austin Healey. "Like my father, I liked British sports cars. And still do,” he said, adding that he spent a lot of time by the side of the road waiting for tow trucks when he was younger because of unreliable British automobiles. "Suffering for style because they are cool looking cars, but they aren't very practical."

Both Bright Lights, Big City and Bright, Precious Days also feature hilarious scenes with ferrets. And there are drugs in both. But I’m not suggesting McInerney has just rehashed his first book. Far from it. While the writing in his latest might be more sedate than in his debut, it’s more assured and the characters have more psychological depth. For me, reading Bright, Precious Days was like re-discovering an old band I used to like but had, for whatever reason, stopped listening to.

*

As we spoke, McInerney drank from a mug with a Penguin cover of The Great Gatsby on it, which seemed a bit too perfect given that I’d found it impossible to not think of that great American novel when I read Bright, Precious Days. Although, like all of us, McInerney read Gatsby when he was young, it didn’t make an impression on him the way The Sun Also Rises or The Catcher in the Rye did. But once people started making comparisons after Bright Lights, Big City came out, McInerney went back to Fitzgerald’s work, was inspired and admits he’s been influenced by him ever since.

He bristles, though, when readers describe Russell and Corrine Calloway as fabulously wealthy. The couple at the centre of Bright, Precious Days, don’t have particularly lucrative jobs by Manhattan standards. Russell is a publisher of literary fiction and Corrine runs a non-profit. And their city is a Darwinian place that has priced out people who haven't succeeded or who work in lower-income fields. So the Calloways rent their one-washroom loft, eat out only three times a week—about four times fewer than everyone else in Manhattan, jokes McInerney—and hang out almost exclusively with people who are richer than they are. Still, most readers would likely consider them fabulously wealthy even if no one in New York sees them that way.

But the protagonists’ relative economic status is integral to the novel, which takes place between America’s mid-term elections in 2006 and the financial crisis and the election of Barack Obama in 2008. “For me, it's important that Russell and Corrine, even though they are glamorous, are in some sense something of an Everyman, Everywoman,” he says. “And even though they live in this really exotic setting of New York City, their struggles really aren't that different than people living in small Midwestern towns. They're struggling to keep up.”

In a 2002 piece called “Why Gatsby is so great,” McInerney noted, “Fitzgerald's best narrators always seem to be partaking of the festivities even as they shiver outside with their noses pressed up against the glass.” That’s also true of Russell Calloway, who, though he isn’t the narrator, is not unlike Nick Carraway: he observes a socioeconomic culture where people have more money but aren’t necessarily better or smarter people. And the setting is similar. “It's not deliberate,” the author says, “but certainly I like to think there's some continuity between Fitzgerald’s fictional New York-Long Island and mine.”

McInerney, who moved around a lot as a kid, has made Manhattan his literary turf the way Carver made the Pacific Northwest his and Alice Munro has made Southwestern Ontario hers. He’s fascinated by the upper echelons of New York, a world not many people have access to and not many people write about with realism. “And,” he says, “there's a lot of fodder for satire there.”

At one point, Calloway goes out for lunch with a possible investor and watches a pissing match between oenophiles: his host and a table of financial hotshots send glasses of increasingly rare wines back and forth in an effort to impress each other. McInerney wishes he could take credit for completely inventing this scene but it wasn't too far off what he saw back in 2006 and 2007 at Veritas and Cru, two “meccas of wine worship” that boasted $5,000 and $10,000 bottles on their lists. His celebrity as a novelist and wine columnist meant people often offered him glasses of expensive vintages (similarly, many people offered him cocaine after Bright Lights, Big City came out). “You can't write about New York without making fun of a lot of the ridiculous behavior,” he says. “I mean, if you did, you'd be a fool.”

Inevitably, the other book I thought of while reading Bright, Precious Days was Bonfire of the Vanities. McInerney calls it a great New York novel, thanks to Tom Wolfe’s talent as both a stylist and a sociologist. The two writers ran into each other at a dinner in late 1984 or early 1985, and the man in the white suit said, “You did something really cool there. Nobody's written a literary novel about New York in years.” At the time, Wolfe had been going around saying the novel was dead. “That stuck in my mind,” says McInerney, “because three or four years later, he wrote a very big literary-slash-commercial novel set in New York. So I like to think I had a bit of influence on him.”

Although Wolfe mocks relentlessly, McInerney oscillates between satire and romance. Some chapters in Bright, Precious Days are more Evelyn Waugh or Wolfe, he says, while others are more Fitzgerald. Sending up the lives of the affluent is part of his objective, but far from the point of the book. After all, like everyone else, New Yorkers struggle with questions of life and love and fidelity and family.

While Wolfe seems contemptuous of all of his characters, McInerney is fond of the Calloways, whom he first wrote about in 1992’s Brightness Falls and then again in 2006’s The Good Life. “The only thing that keeps me from liking Bonfire of the Vanities as much as Balzac's great novels, for instance, is there's nobody that I really identify with or care about terribly much,” he says, before pointing out that Wolfe isn’t trying to make us care about them. “I genuinely like Russell and Corrine or I wouldn't keep writing about them.”

In fact, he’ll likely return to them in a future novel. He doesn’t want to follow them into assisted living—he is, by his own admission, too much of a glamour hound for that—but, at only fifty-one by the end of Bright, Precious Days, they aren’t ready for the old folks home just yet.

In the meantime, he’d like to think people in other parts of the world, rural and urban, can relate to them. After all, money and bright lights aside, most of their problems are normal ones. “There is the issue of what dress Corrine is going to wear to the gala,” he says, “but most of the time she is dealing with more fundamental questions.” These include their kids, their jobs, their home—and their marriage. “Ultimately, this book is about marriage and relationships as much as it's about making fun of rich people,” he says. “More than it's about making fun of rich people.”

*

McInerney’s current wife is Anne Hearst, sister of Patty and granddaughter of William Randolph. At 62, it’s his fourth marriage. So it’s a subject he was some experience with.

Fidelity, he argues, is the central question of marriage and the eternal question that the domestic novel—including classics such as Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary—inevitably deals with. “The interesting marriages are the ones that survive the crises rather than the ones that sail placidly along the untroubled waters,” he says. His parents had a good one, but his mother had an affair. “I think my mom was glad that she stayed in the marriage. In the end, she believed in it.”

To their friends, the Calloways seem to be the perfect couple. They aren’t, of course, and both have had affairs. But they’re still together after more than twenty-five years. The book considers whether it’s different when a husband cheats than when a wife does. And McInerney wanted to see how far you could push a guy like Russell before the marriage’s trust was irreparably broken. “Male infidelity is certainly less surprising and it seems to be somehow less consequential,” he says, suggesting that it’s a dog bites man story when a guy cheats on his wife and more of a man bites dog story when a woman cheats on her husband. “I think where it really differs is the whole question of what's forgivable, because male pride is a much more obdurate thing than female pride.”

*

In 1984, McInerney’s publisher told him the novel was dying and nobody his age read, so while he’d written a good book, he shouldn’t have any big expectations for Bright Lights, Big City. That sentiment was wrong then, and a succession of writers—he cites Nathan Hill as a recent example—have proven it wrong ever since.

So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that Bright, Precious Days is also about books and the publishing industry. McInerney says his relationship with Fisketjon, who has been editing him since he was writing short stories in college, informed the characters. But anyone who knows the infamous controversy over how Lish edited Carver will hear echoes of it in the relationship between Russell and a young short story writer named Jack Carson.

I asked McInerney if he preferred Lish’s versions of Carver’s stories or Carver’s versions. His take: “I hate to say it, but I kinda like both.” Which was an answer I really liked. I told him I’d seen Carver at the International Festival of Authors in 1984. He’d read “Cathedral,” a story I’d initially come across in The Atlantic in 1981 and loved, but when I heard Carver read it, I suddenly realized how funny it was. McInerney, who’d first heard an oral version of the story before there was a cathedral in it, told me, “He always made things funny when he read them.”

For many people in publishing today, there’s not much to laugh about. But Russell’s optimism—or at least his refusal to be pessimistic—about the industry reflects McInerney’s view. The fracturing of the culture means it might be harder for a literary novelist to seize the popular imagination the way he did with Bright Lights, Big City. But he’s encouraged that the novel endures.

Sure, they don’t have the cultural centrality they did in the 1920s when Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner were putting them out. “But I like that young people are still interpreting the world through the vehicle of the novel,” he says, “and it's wonderful that it hasn't died yet.”