In the morning the waves glowed like uranium, a deep sweat coming up off the seafloor. It was beautiful but it was nerve-racking too, being that close to the future.

Then a bloom of moon jellies drifted in, their tentacles dragging behind them like purses. I thought it was a sign, some kind of big money omen, but Joelle said we should get ready to move on, start trucking north—where we were really headed.

For the past month we’d been “down beach,” less than a mile from Atlantic City, camping out in a mail-order bungalow belonging to Thea’s sun-shriveled grandfather. Me, Thea, and Joelle—we’d had it to ourselves—one hundred square feet of no electricity, plus the washed-out fire pit and jack pines.

“I want to try the Taj,” I said. “I have that feeling.”

That feeling had done well for me so far.

At least it had kept Thea and Joelle in tallboys and blobs of Coppertone, and that day, for lunch, we had lobster from a shack that seemed too legit to be real—a wonder that in between the boardwalk’s Shoot the Gimps and the constant grind of tattoo joints we’d found J’ean, the Lobster Man, two samples from his morning’s load of big’uns in his baloney-colored fists.

J’ean was headed north too, back up buggin’ lobster on Eastpot.

“New Jersey lobster?” said Joelle. “How shitty does that sound? I mean, by comparison.”

J’ean just shrugged. “Goin’ to breeze up today,” he said through the slice of his hand.

That put an extra volt through me. I loved storms. I turned toward the ocean. It was still August but now the waves looked like sandwich foil that had been crumpled up and hucked away. I was in a hurry. The boardwalk was an ongoing line of cracked wood; it stretched forever.

“Let’s take a cart-pusher,” I said.

A rickshaw cart was extravagant, but we were leaving soon. Joelle had a job to get to in New York—she referred to it vaguely without offering even one giveaway detail—and Thea’s sister had just popped out twins into the Grey Goose-saturated swamps of western Connecticut.

Babies! How wild. We bought them pint-sized T-shirts and joked about their names. Felix. Maude. We loved them already as an idea.

Thea was a week late for her obligatory nanny gig. No biggie, she said. That was Thea. We’d been something two years ago, had been so looped on pints of tequila and what she called sloth weed that neither of us remembered much. The non-memory was connective.

BEACH! Thea had said on the phone, a month earlier. She knew I was depressed in New Brunshwick. Bored and hot. Joelle’s here, she said. You’ll like her. You’ll see.

But Joelle was different. My crush now seemed like something I’d been born with. Plus Joelle was smarter than me: her brain had that slaughterous left hook.

“The Taj,” I said, aloud.

The long line of cart-pushers stretched toward the casino action. It was a casual, twenty-four-hour kind of job. We passed two snoring against the cracked vinyl benches of their contraptions but the next guy along looked scarily awake.

“I haven’t slept in three days,” he said.

“Awesome!” said Thea.

“Really!” he promised.

He must have been fifty, a meth-head probably. I assumed they all were. His hair was sticking up but he had a nice face.

*

There was a haze over the boardwalk. I couldn’t tell if it was the heat or the breeze up, sucking aloft those clouds of sand. I felt clammy pressed in between the two of them. A line of sweat slurred along my chest binder. There was a time when I was sure I would get surgery, when I stayed awake late staring at the plaster wall. I’d made an appointment with the surgeon even, checked the box: payment plan. A giddy, raw feeling. How could it not mean change?

The cart jerked forward. I stuck my palm between Joelle’s jean shorts and the seat. We hadn’t been alone together since we first mashed faces two nights ago, which meant sex with our clothes on, a bunch of fingers, punk shots at best. We lay next to each other in the violet half-light of the bungalow’s only room—not caring much about Thea but pretending to care, keeping sort of quiet. We were accelerating particles about to separate. Soon we’d be peeled apart.

“It’s just a body,” Joelle had said, when I bucked her hand away from where she was trying to insert it.

“Sure,” I’d said, bleakly.

“Okay, yeah, it’s internal. But it doesn’t have to be domestic.”

I rolled away from her, from the king-sized futon the three of us shared, our only furniture, the raft in the middle of our floor. I tugged the sweat-stained material back into position over the slack mounds that on good days I pretended were giant pecs. Joelle leaned down and put her thumbs against my temples.

“It’s Thea, right?” she whispered. “You’re so shy!”

“Yeah,” I said.

This had nothing to do with Thea, but then again, I hoped it did. I was a concrete bunker pretending to be a friendly, all-access picnic area. I scrubbed a small pile of sand across a floorboard. Joelle was naked more than not.

The next time it happened, she stared at me from far away.

“Why don’t you just cut them off?”

*

Our cart neared the strip. First was Bally’s. Bally’s had a Wild West front, with sheriffs and hookers painted all over it. It was ridiculous but secretly it turned me on.

“Yee-haw,” said the cart-pusher.

“Get a room,” said Thea, elbowing me.

My body was trying to wedge itself underneath Joelle’s. It must have been something floating from her pores.

Two teenagers ran out of the air-conditioned saloon doors, flinging off their Nets jerseys when they hit the hot. I stared at the bank of their bare torsos. There was a sink in my old studio building with a sign hanging next to it. “Black Mold,” it said, a Sharpie-drawn arrow pointing down into the dirty plastic interior. My painting summer was gone and not much to show. I’d drawn exactly one still life: an oyster and a flattish grape.

“Can’t go in Bally’s anymore,” said our cart-pusher, nodding it by.

We were cruising faster now.

“When I started this job I was pants size thirty-eight,” he huffed. “Now look at me, I’m thirty, thirty-two!”

He wore his expression like a founding father. Someone you could trust.

*

In the Taj Mahal, gold chandeliers spaghettied from the ceiling, gaudy and awful. I played Frontier, drawn into the vortex of radioactive desertscapes and howling coyotes, and then immediately hit it big on MJ’s Moonwalk. A thousand bucks on my second spin, zing zing zing! “Billie Jean” exploded from the speakers while a rocket sprayed MJ with moondust.

Joelle sat next to me, smoking.

“Let’s get a room,” she said.

When you score like that the hospitality staff comes over—they don’t want to let you alone. We stared up at two managers and a tired-looking hostess whose sole job it was to get me drunk and playing again, tout de suite.

“We’re very happy to have you here, Mr. ...” They trailed off. “Very happy.”

The manager in charge smiled olympically and handed me a plastic card.

“We’ve put you in the Chairman’s Tower,” he said, “ocean view.”

“Yeah sure!” I said, chewing my lip. I was sweating but I wasn’t sure why. Everything was the same, but outside it looked very dark.

“Do you have any tequila?” I said. They hustled it over to me in a plastic Taj cup. It must have been a slow day. Thea had evaporated, probably reading at the bar, and I thought about strolling over to her and swinging her around as the skirt-thing with legs she’d recently been wearing swooped. I’d always been comfortable and drunk with Thea, half-blind, in a warm cave.

Then Joelle and I were in the elevator, grinning, pressing all the buttons at once. I clamped my voucher ticket. A thousand bucks, we said back and forth to each other. A thousand bucks! It was that free kind of money that you could do anything with. Joelle wanted me to cash it in so we could throw it all over the bed.

“Just for fun,” she said. “Then you can call that surgeon.”

I thought about the old Biggie video, the stacks of cash flying everywhere, the helicopters, the epic yacht.

“It’s only fifty twenties,” I said. “Is that really enough?”

*

Our room faced east as promised. There were smudges on the mirror and cigarette burns pocked into the heavy carpet. We sat at the little coffee table and I stared at Joelle. My neck felt prickly. She’d gotten tan, really dark. She was Italian. Her Italian-ness and double-jointed thumbs seemed like perfect chemistry. She wiggled them idly as she smoked. Now the water looked like a series of yellow planks and the sky was hot and gray. Joelle took off her shirt in a motion so convincing I wasn’t sure she’d ever had it on. I wanted to ask her about the job in New York but stopped. The room felt thick after all our time out on the beach. The wall-to-wall. The so-far-undented carpet space near my feet where we should fuck, astral wand, blow our minds et cetera, after, and only after, we did it in the shower and on the ample bed. I twisted my plastic cup of warm tequila.

“I should get some ice for this,” I said.

In the hall I began to walk toward the elevator. Soon enough, I was back downstairs. Grit had settled on the machines in my brief absence. I re–fed in my ticket and thought about moon jellies. They were see-thru but vacant. It’s just a body, said Joelle. On the screen, the aliens and their queen, Michael, were changing colors and shapes before my eyes.

The $1,000 became $963. A minor subtraction. I would’ve spent it anyhow. Plus, I still had that feeling.

When I looked up again, it said $815 in the lower left corner. I should find Thea, I thought. She’d love this. I wanted to show her the whole ticket, the $1,000. I increased to MAX BET. Wind blammed against the boardwalk-facing plate glass, the windows of my chest.

MAX BET MAX BET MAX BET.

There was no one around; the place seemed practically evacuated. This is how the game works, I told myself. If you quit now, it’s got you, you’re a real loser. In front of me, craters opened up in unison, spewing confetti. Each eruption seemed like a sure win. But still the left corner dwindled. I began to think of Joelle, topless in the room. It seemed dumb that I had left. Worse than dumb. Abyssal.

I knew I should take the ticket out, but I couldn’t. The lizard part of my brain kept saying: the next spin is the one. I had another tequila. Then a few more.

I knew a guy back in Albuquerque whose foot went numb from a skateboarding accident, then turned an angry celery color. Eventually they had to cut it off. He was okay through the operation but in the recovery room, goopy with anesthesia, he became obsessed with wanting to keep the foot. He was going to taxidermy it from toenail to ankle, he said, and freestyle it into a lamp. The surgeons gave it to him reluctantly. After all, it was his foot, what could they do? He stuck it in the freezer and five months later, when the taxidermist was ready, he got the lamp.

“What happened next?” said a voice next to me, a bun-sporting granny zinging away on Miss Kitty.

“Nothing happened,” I said. “He was a real weirdo.”

“Well, did the lamp work?”

“Yep. He said it had a nice homey glow. But then one day he came home from work and his dog and the lamp were gone.”

“Did he put out an APB?” She hit a LITTERFEST!, and the siren atop her machine flashed like cherry Jell-O.

“He did,” I said. “Except it was just part of him that was missing. A missing foot report. They found it down by the viaduct, the place the accident had happened to begin with.”

I paused for effect.

“Well,” she said.

“It was gnawed to pieces,” I said with relish.

It reminded me of a dream I’d recently had where a shark circled my chest hungrily and I felt relieved.

The coins from LITTERFEST! stopped ringing and she began to hum.

“Lord, I should cash this,” she said.

She flashed me her sleeve hem and no fingers, just a cauliflowering stump atop her old wrist, the skin fused to itself in tight folds.

Then she was gone.

*

I was sweating swimming pools. What’s that horrible sound? I thought. But it was just the deafening silence of Moonwalk. I stepped into the bejeweled elevator with an awful chewing in my gut. There were a million times I could have stopped. It wasn’t free money. It was a chunk of something.

I fiddled with the floor buttons but this time they were sticking in their slots. I was there in the mirror—my sloping body, my very own continental shelf. They hadn’t found the dog after all, that was the sad part. It had just loped off. Already I was begging Joelle to forgive me. On the closed face of the elevator doors, a prayer from Emperor Shah Jahan floated over a flat Taj Mahal:

The sight of this mansion creates sorrowing sighs;

And the sun and the moon shed tears from their eyes.

But in the room, Joelle was missing. The cleaning service was vacuuming up our nonexistent mess. I sat down on the bed.

“He was in here,” said Joelle’s voice. She was talking to Hotel Management in the hall.

“He was just sitting there like a total SOB.” She moved through the gold-trimmed doorway.

“Oh,” she said flatly, “it’s you.”

Apparently some skuzzbucket had entered our room while I was gone. Had sat down on the bed, just like I was doing. When Joelle came out of the bathroom, he was flipping the channels.

“This asshole?” said Hotel Management, pointing at me.

“No, not that asshole,” said Joelle.

Now she was livid.

“I’ve charged some things to the room,” this new Joelle told me. “Majorly $$$ things.”

“Uh-huh,” I said.

“But you can cover it, right?”

“Uh-huh,” I said.

The TV was still on. The news anchors were saying things like “level two” and “hurricane” and “South Carolina.” Was the Chairman’s Tower wobbling?

“Don’t leave,” I said to Joelle.

“This is still our room, right?” I said to Hotel Management.

*

I went in search of Thea. She appeared, a bright hole in the gloom, at the Rim Noodle Shop bar.

“You look like a train wreck,” she said. “No. More like a train who, for no reason, stopped and then tipped over. What happened to you?”

“Two tequilas,” I managed, to the barman. Boy was it dark.

“It’s a hurricane out there,” I said. “A big one. If it’s not here yet, it’s coming.”

“Uh-hm.”

Thea seemed skeptical, but I sensed a radical shifting of things: a new world order.

“Thea?” I said.

I had a decision to make but I wasn’t sure what it was. When I leaned over and tried to put my mouth near hers she hit me.

“You idiot,” she said. “You idiot idiot idiot. You NERD.”

*

I took the same cart-pusher back to our bungalow. Rain globbed against the sand. I was hoping Joelle and Thea would be there—at least, I thought I was. My skull was hot.

“Found you!” he said, elated.

What a great new life without sleep, I thought. We rolled on. Caesar’s, Trump, Tropicana.

“Can’t go there anymore,” he yelled at each one over the thump of the tires.

“Why’s that?” I yelled back.

“You drink?” he said.

“Who doesn’t?”

“They kept handing me screwdrivers, buying me stuff with Visas, Mastercards. Everything premium, I was happy as shit!” He paused. “Shit went south real quick.”

I nodded. “It usually does,” I said.

“I was running,” he said, “as fast as I could. But after a while, I just stopped. I got right up into those pigs’ faces. I really wanted to know.”

The light was gone. Between the drops, the beach stretched out, a fossil of itself—all wear and cruddy ridge.

“Know what?” I said.

“I mean, somebody had to have the answer!” said the cart-pusher, doing his best George Washington. “They had me by the short hairs, I was bawling like my life depended on it, but I had no idea what for!”

*

At home, Joelle and Thea were on the phone, which meant crouching in the bog bushes behind the cabin. It was the only place with reception. I followed their voices and the blue cellular glow.

“It’s Thea’s sister,” Joelle informed me, glaring. “The twins are sick. Their fevers are climbing past a hundred and four.”

I lay down on the sandy wash. It was intuitive, canine. The lower to the ground I got, the better. I wanted to pull Joelle down on top of me and bury my face in a hunk of her rain-sticky hair.

Thea covered the phone with her hand. “I can get a flight,” she said. “But there’s a weather advisory? I have to go now.”

“Can you help her?” said Joelle, looking at me hopefully for the first time since Moonwalk. Joelle had money but it was all glommed up in something, her father probably.

I thought about my empty wallet, my art school economy. I scrubbed the ticket out of my pocket and handed it over slowly.

“Three dollars and twenty-four cents?” said Joelle.

I’d painted the Taj Mahal once in a class. My dome had a nice full onion shape but those moon-facing spires that lined the central tomb had confounded me. Somewhere around their midsection they’d rebelled—sticking in every direction but up. My art teacher threw out his hands.

This is all about Love! he’d said, pacing. And Sacrifice! You’re so terrestrial. You’re scared to leave the ground!

I looked at my spires, their tips lopsided and heavy, tugging down toward earth. Boobs, I’d thought. I was too embarrassed to say my Taj was already on the moon, that’s how I’d understood it in the first place.

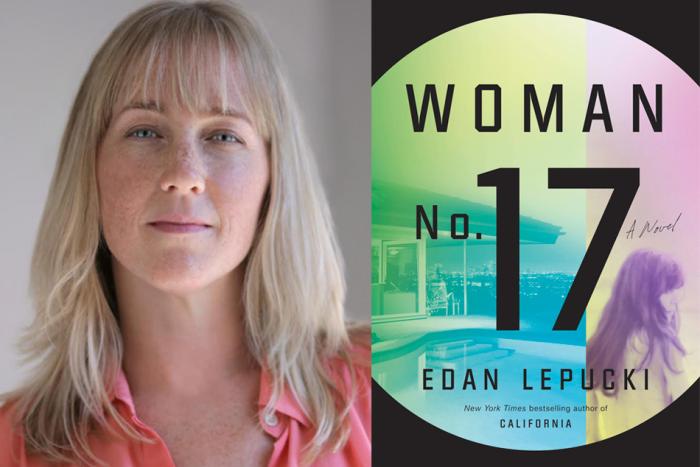

This story appears in Large Animals: Stories by Jess Arndt, published in May 2017 by Catapult. Photograph by Jess Arndt.