In Edward Albee’s first play, The Zoo Story, an anguished wanderer orates on pornographic playing cards: “When you’re a kid, you use them as a substitute for a real experience,” he says, “and when you’re older you use real experience as a substitute for the fantasy.” Albee was one of the major literary heroes of my high school years, and when I watched the movie adaption of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? with my first girlfriend, the witty, vindictive warhorse couple of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton seemed both aspirational and abject, like looking into a doomed but beautiful future. Being young enough to aestheticize cruelty with no moral remainder, we used Albee’s plays as a substitute for real experience—how glamorous to be professors, to drink and to hate each other. Now, some fifteen years later, I actually teach at a college; my fantasies rarely involve charged banter with a drunk wife.

Two years after that first viewing, though, in a third-floor bedroom decorated with paperbacks and cigarette-stuffed wine bottles, I watched Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? again. I was in university by then, and the room was filled with the full cast of that era of my life, English majors or people, like me, who were too snobby about books11“No one understands books less than critics” —nineteen-year-old me to be English majors, but who treated literature like a competitive sport all the same. Most of the people in that room would go on to fuck and fuck over one another—we hated and loved each other with equal force, and it struck me as appropriate that we were watching this strangely dull classic. Pace the entry-level No Exit, but with the possible exception of Scenes from a Marriage, the prison of other people has perhaps never been more relentlessly wrung than by Albee, and has certainly never been as funny. “My wife’s in the can with a liquor bottle, and she winks at me—winks at me!” says the young buck in the midst of his first real marital meltdown. “She’s never wunk at you?” says Elizabeth Taylor, totally deadpan, to this sweet, beautiful idiot. If there’s a patron saint of smart people being mean to each other, it must be Edward Albee.

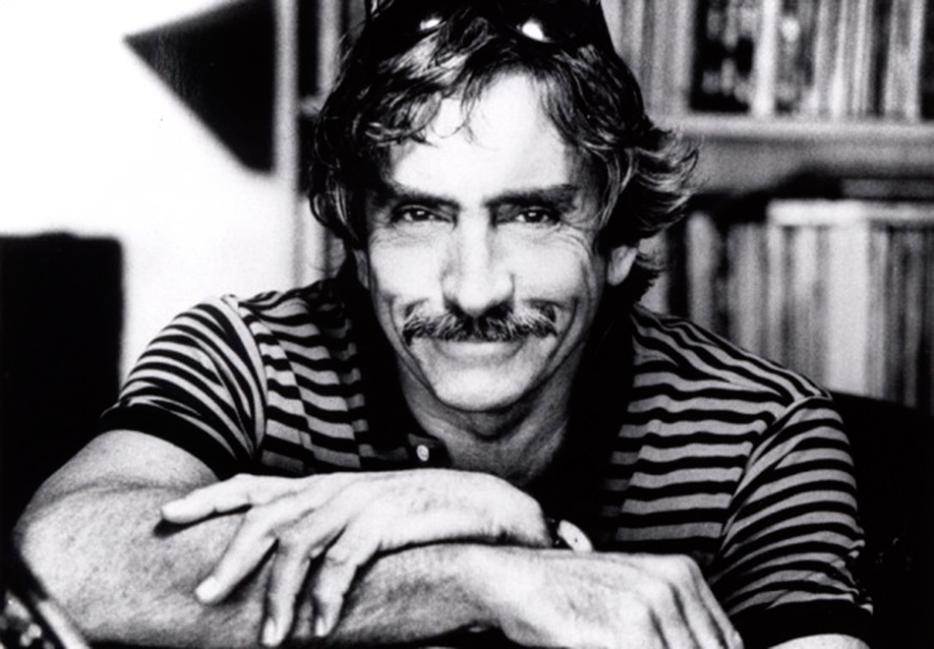

I persisted in being smart and mean for several years after that, but I stopped thinking about Albee for a while. I don’t think he would mind if I admitted I assumed, back then, that he was already dead. Despite his contemporary rhythms of speech, his plays seemed to issue from an irretrievable past. After university, I wrote two plays, Albee not crossing my mind, but his syntax and sensibility shot through both of them. I didn’t understand theatre, though, and my scripts disappeared into Dropbox. I had more success with prose, and in 2010 I relocated to Alabama to pursue an MFA. In the winter of my second year, I sent a short story called “A New Place” as my application to an artist residency in Montauk, New York. That April I received a letter informing me I’d been accepted. The residency was sponsored and managed by Edward F. Albee, who I now realized was alive, and the welcome package said he resided there in the summers, and hand-delivered residents’ mail to them each morning. I did a little dance in my living room on 7th Street.

This man had already done so much for me, but he had not brought me my mail.

I flew into LaGuardia and took the “Montauk Jitney,” an anachronistic-sounding bus service that transports mostly an uncanny valley of people rich enough to be going to the Hamptons but too poor to not take a bus. Roy, the groundskeeper, a gentle curly-haired man, picked me up and drove me to “The Barn,” as it was called—an actual huge, drafty barn where four other people and I would live together for six weeks—a stark, weird, minimal setup not unlike the premises of an Albee play. I had previously known Montauk only as the place Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet meet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. I now saw it was a fishing village on a beach with a Momofuku Milk Bar.

During my time there, I organized hundreds of old emails for an autobiographical novel I never figured out how to structure, carried bags of groceries along the well-kept country roads between The Barn and the town, posted videos of my residence-mates’ hair products to YouTube, and did everything but write. In one of my many breaks from not-writing, I found the Paris Review interview with Albee in the Fall 1966 issue that just happened to live at eye level on one of The Barn’s bookshelves. I brought the magazine out to the lawn chair under the large tree beside the picnic table near the back door. In the interview, Albee talked about writing his first play when he was twenty-nine, after giving up on so much else. I was then twenty-nine myself, and every day felt like giving up. I was lying in this man’s lawn chair. The light came down through the leaves a little at a time.

This man had already done so much for me, but he had not brought me my mail. I wanted to meet him. It felt gauche, but I have never had good manners, and so I pestered Roy about it. “He wants to come out,” said Roy. “Maybe next week.” Next week turned into next week into next week, though, and then the five of us had a bonfire on the beach and then it was time to go.

Roy was going to drive Michael from Utah and me to the train station, and while we were waiting for Michael I asked Roy whether, since Albee hadn’t been able to make it out, I might somehow be able to visit him in the city. I’d written a play I wanted to discuss with him. Roy gave me Albee’s assistant’s email address. On the train into the city, Albee’s assistant asked for the play and my phone number, and said Edward, if he was up to it, would be in touch.

I stayed in an empty apartment in Williamsburg and for a week worked mostly on the play. On a Thursday, at 3 p.m., my phone rang.

“Hello?”

“Hello, is this Stephen Thomas?” Low growl, hard to make out.

“Sorry?”

“Is this Stephen Thomas?”

“Yes,” I said. “Who’s this?”

“Edward Albee.”

“Sorry?”

“Edward Albee.”

Edward Albee confirmed I was interested in a visit, and a week later I was on the street outside his Tribeca apartment.

The door opened, and I was greeted by Edward’s boyfriend, Alex: twenty-four, very skinny, very tight black jeans, black hair. He led me into what seemed to be a private elevator. We went up one floor. The door opened. Edward Albee was standing in his living room, waiting for me. He looked like a marmot.

“Stephen Thomas, I presume?” he said.

“Edward Albee, I presume?” I said.

“Awl-bee. Awl-bee,” he said.

“Awl-bee,” I said.

Alex went to make tea and Edward invited me to sit. He complimented me on my story. “I liked how it sort of fluttered around. It felt very loose and free. Have you tried to publish it anywhere?”

Two things: I was very flattered, and I realized there had fully been a fuck-up. Edward had received “A New Place,” the story I’d submitted to get into the residency, not the play, called Dogs,I was hoping to discuss. Somehow we managed to get past this, and, after Edward graciously invited me to come back with the correct text before I left New York, we settled into conversation.

I thought that if this was an Edward Albee play, I would stab him with the pointy head of one of his African sculptures, or stab Alex, stab someone at least, or stand up and narrate a long story heavily implying I was about to, or had already, in some metaphysical past.

He asked me about my life, where I’d grown up, my parents, how I’d gotten into writing. I felt the glare of the spotlight illuminate my pre-packaged soundbites as the bits of sitcom dialogue they were, and I kept trying to turn the conversation back to him. He would gently non-answer, though, and deflect, and deflect. A little flustered, I asked him what he was working on now, thinking this would be the polite way to phrase it, but as soon as the words left my mouth I realized my error. Anger darkened his face for a second and his bushy brows seemed to spell out his crossness in a way that felt fatherly. This was all in less than a second, and then his marmot face was inscrutable again, and old.22“My sacks are empty, the fluid in my eyeballs is all caked on the inside edges, my spine is made of sugar candy, I breathe ice; but you don’t hear me complain. Nobody hears old people complain. [...] Old people are [...] twisted into the shape of a complaint.” —Grandma, The American Dream. Evenly, and without recrimination, he said he’d been recovering from open-heart surgery, but he was getting better.

I said I was glad to hear that.

He continued to interview me, during which I felt increasingly fraudulent. He drew the conversation back to my story, and quizzed me on my favourite writers, which seemed most interesting to him. I hate talking about writers I like and tried to choose as neutrally and blandly as possible. I said I liked Tolstoy. That seemed fine to Edward. Alex came halfway down the stairs and asked if we would like more tea. Edward, without turning around, or asking me, said we were fine. Edward caught my eyes and asked, “Does writing fill you with fear or joy?”

I had long since stopped trying to extemporize witty apothegms, which I’m not good at anyway, and, after thinking about it, I said, honestly, “A little bit of both.”

Edward walked me around his airy loft. It had maybe a hundred thin-faced African sculptures of the kind I’d seen through a dusty window in a locked shed up a hill at The Barn, crammed in beside the leftover art supplies of Jonathan Thomas, Edward’s partner of thirty-five years, who died in 2005. Alex came down the stairs again and joined us. We came to a piece Alex had done. It was mixed media flattened onto a canvas and shellacked, and something about it reminded me of what I’d seen of Jonathan Thomas’s work. Edward asked if I liked it.

The next day, I dropped a copy of my play at the foot of the door of the elevator outside—there was nowhere to actually put it. Edward called again, and the day after I was back in his apartment. We talked about my play, and Alex was much more present this time. Albee thought one character wasn’t real, and Alex took up my cause, saying, “It’s normal these days for not all the characters to be people.” Edward wasn’t convinced. “I think you should see it on a stage. See what you think.” I asked him outright if he could help me do that. He gave me the name of a director in Toronto, but, ungrateful brat that I am, what I wanted was the name of a director in New York, and I thought that if this was an Edward Albee play, I would stab him with the pointy head of one of his African sculptures, or stab Alex, stab someone at least, or stand up and narrate a long story heavily implying I was about to, or had already, in some metaphysical past. Instead, I thanked him obsequiously and got up to leave.

What was the real experience of meeting Edward Franklin Albee for two afternoons in his Tribeca loft at the age of 84? He was generous with his time. He was interested in new people. He wasn’t easily swayed from his opinions by some rando, or by his boyfriend. He seemed a little vain, but I’m sure the world invited him to be so. He was dating someone a third his age. He kept his old lover’s sculptures around. I learned, I think, from a very brief moment of access into his intimate daily life, almost nothing—that as a human with a personality he was very normal, and he behaved exactly the way anyone in his position would. He had successfully sold his thoughts for money and was now living well. When you’re older you use real experience as a substitute for the fantasy.

On my way out of Edward Albee’s apartment for the last time, he reminded me of The Barn’s policy of acquiring one copy of any book published that had been worked on at Montauk free of charge, and I said I would be honoured to send him a copy of anything I published. I did publish a book six months ago that I worked on there, but a copy still sits on my shelf with a Post-it note reading “Albee” that he will never receive.