“If cinema was a painting, time would be the paint itself,” said Richard Linklater a couple of years ago after the release of Boyhood (2014), his twelve-years in the making experimental drama following the formative development of a Texan youth (played by actor Ellar Coltrane as he aged from from six to eighteen). A brilliantly executed work of morphing portraiture, Boyhood was received as a career peak for a filmmaker whose cinema resembles a canvas that's constantly being re-drawn, while certain shapes and shades keep bleeding through the fresh strokes.

Twenty-five years after the landmark release of the putative Gen-X manifesto Slacker (1991)—a movie whose limited attention span for conventional storytelling turns it into an awersomely atomized ensemble piece—Linklater has retained his reputation as an industrial outsider. His films constitute perhaps the most experimental body of work of any American narrative filmmaker of his era. In addition to making at least three feature-length films without a conventional plot (Slacker, Dazed and Confused and Everybody Wants Some!!), he's done two roto-scoped films (Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly), created a trilogy that follows the relationship between two characters over twenty years (Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Before Midnight) and shepherded Boyhood to completion by shooting for a few weeks each year between 2002 and 2014. It's hard to think of an American filmmaker who has tried so many different things without ever losing his or her voice.

Autodidacticism is one lens through which to perceive Linklater's career to date. His first short, 1988's It's Impossible to Learn How to Plow By Reading a Book, is a wry celebration of self-directed learning. Another is autobiography: few directors are as eagerly self-inscribing. Linklater memorably appeared onscreen in Slacker (1991)—a plotless ramble through bohemian, pre-Millenial Austin—and then showed up a decade later in that film's spiritual sequel Waking Life (2001), asa backseat driver hinting to the film's hero (Wiley Wiggins) that he's going to have to choose the direction of his own life.”

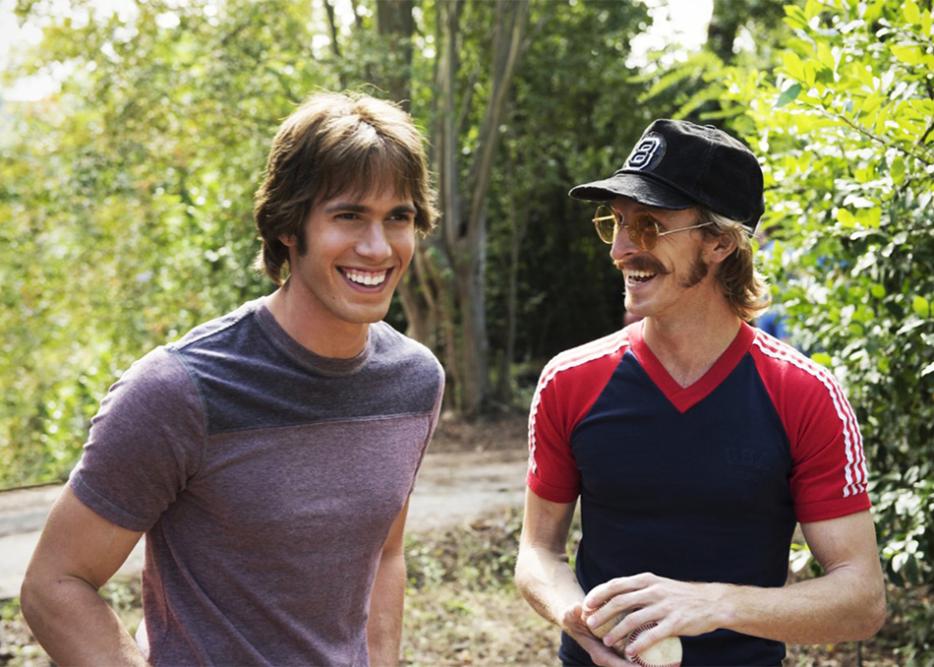

That same theme of choice permeates Everybody Wants Some!!, which comes advertised as a “spiritual sequel” to Dazed and Confused. , except with the witty female characters scooped out and replaced by a series of slinky potential undergraduate conquests. The gender imbalance is notable, but the film isn't simply a jock-triumphalist celebration. Without overplaying his hand—or dampening the overall good-time vibe—Linklater has fashioned a kind of critique in which his heroes' constant competitiveness (at ping pong and video-games) and locker-room one-upmanship becomes symptomatic of larger cultural undercurrents and ingrained gender expectations (and gets gently corrected along the way, at least for some members of the ensemble). These big men on campus carry themselves with a confidence that's belied by little stings of inadequacy, and the dialogue constantly reminds us that the skills that have gotten them this far can look paltry in a larger talent pool, an apt metaphor for the myriad wake-up calls of adulthood. Linklater takes the optimism of youth—the idea that a better world is right around the corner—as seriously as his young characters deserve.

When Linklater was in Toronto promoting the film, I interviewed him in front of a group of graduate film students.

Everybody Wants Some!! has been described as autobiographical, and you've been inscribing yourself in your work for a long time. For instance, in Waking Life, you play a character navigating a boat that's taking the protagonist along—it's a cameo, but it also seems to be about narrating the direction of your own life.

I always think like a novelist: “This is my life, and it's where I live.” With Waking Life, it's autobiographical, but it's also film autobiographical. In the film I made ten years before Waking Life, Slacker, I'm the guy in the cab, driving around. I wanted to revisit that same deterministic idea, ten years later. It fit my own cinematic thinking, and my own cinematic world. Waking Life is a cinematic fever dream, and it's all in my own little world.

There's also a bit in Waking Life that's very much like your first feature It's Impossible to Learn How to Plow By Reading Books, in which a character arrives at a train station.

It's a very oblique little narrative, and I was documenting a lot of travel. I still like that very much. Like in [Everybody Wants Some!!], it starts with the new guy arriving to school, with his possessions. Something about arrivals and departures is interesting to me.

Waking Life also has a scene that's like an unofficial sequel to Before Sunrise, where Jesse and Celine are talking together in bed.

They had no idea what I was doing. I said to [Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy] 'come to Austin and we're going to do this scene.' They were trying to figure out what we were doing, like if Celine and Jesse were real, or if it was a dream... and doing that really kicked us off because without that scene in Waking Life there wouldn't have been a trilogy, there wouldn't have been Before Sunset. It got us thinking about revisiting.

Are there a core group of films you've made that you think are linked by this impulse to revise and revisit your work?

Not really. It's kind of random which ones I revisit. I wouldn't have predicted that I would have made a trilogy out of Jesse and Celine, or that Everybody Wants Some!! would relate to Dazed and Confused. None of it is that thought out or planned in advance. It just sort of rolls out that way.

You've talked about the personal aspects of Dazed and Confused, but I wondered if the decision to set in in 1976, during the Bicentennial, was a reference to Robert Altman's Nashville, which is also a sort of ensemble piece with multiple plotlines.

It was just an autiobographical decision. That's when I was a freshman in college. I could have set it later, like when I was graduating. But you pick a cultural moment that you're trying to say something about. It was pre-punk, pre-new-wave. It had more to do with music than anything else.

One of my favourite scenes in Dazed and Confused is when Cynthia explains the every other decade theory; she's this girl from the ‘70s looking ahead optimistically to the ‘80s, which in retrospect turns out to be a bit of a bad bet.

It did get worse! I didn't do stuff like that in the new movie, that sort of knowing or ironic view. But that was a real thing, the “every other decade” idea. And I did feel that way in the ‘70s, looking forward to the ‘80s.

There are some clear relationships between Dazed and Confused and Everybody Wants Some!! In some ways, the new one starts where the old one leaves off with this student athlete trying to decide if he's going to follow the rules that govern his scholarship.

People forget about that, because Dazed and Confused is a party movie, but those guys are all athletes. They're football and baseball guys. It's a world of athletes. Randall is getting all this pressure from his teammates, because of this stupid thing his coach has come up with.

Were those pledges and rules something you had to put up with when you were playing baseball?

That was something that came from friends at another school nearby. They were making the players sign these pledges. There's always been a thing where [schools] want to tamp down youthful fun. That became more governmental in the ‘80s. There was a symbol of freedom in being able to choose. Anyway, if I could go back to Dazed and Confused, I don't know if it needed that throughline. I've gotten better at storytelling since then. I don't know if it needed an element like that, and Everybody Wants Some doesn't have one. It doesn't need it.

Are the challenges facing the characters in Dazed and Confused very different from the ones in Everybody Wants Some!!?

It's really different. It's as different as high school and college. College is about figuring out what to do with all the adult freedom that's suddenly been dropped in your lap. Dazed and Confused was about the rebellion against oppressive forces in your life as a teenager, when you're a high school student: the institution of school, of family. Then you cut loose from that, and you're voluntarily in college. And then if you want to get a job, you quit. You don't have to do it. I remember being exhilarated by that freedom, but also anxious too, because every decision you make, everything you do, every class you take...you're making these choices that might affect who you become or who you are. Maybe you don't know who you are yet. It's a transitional time of self-exploration and self-discovery and it seemed very poignant. It never ends, by the way.

You mentioned that Dazed and Confused was all about music, and there's huge pop presence in Everybody Wants Some!! as well. The characters listen to all different kinds of music, and it feels very utopian.

That's how it felt. You were listening to funk, or you were listening to metal, you were listening to everything. The music I was trying to reflect in Dazed and Confused was the FM radio stuff that was just coming at you, before you developed your own taste. You liked what you liked, but you were very much steered by pop culture. In college, you learned so much. So many new influences, like your roommates. In Everybody Wants Some!! there are these sixteen guys living together, which was very much my experience in college. They all have album collections too.

There's the scene where one guy is stoned and narrating the chord changes in this psychedelic rock song, and it's like he's trying to share his experience of the music with his friends–to make them love it as much as he does.

Yeah, that's in the bong hit scene. It's from an early Pink Floyd album, and he's talking about finding himself within the notes of the song.

You're much further along in your career now, and Everybody Wants Some!! has a studio behind it—have you felt like you've had to compromise since the movies you were making in the 1990s?

Not at all. I'm very blessed to have made nineteen films without feeling compromised at all. Any compromises I made were ones I did myself. Sometimes you have to accept reality, like making School of Rock for a studio on a $30 million dollar budget. It went well, there weren't any conflicts, but I accepted the world I was in. If it had tested badly, if the ending hadn't worked, I would have been reshooting to try and make it work on a commercial level. Fortunately, it didn't happen. I have friends with horror stories about creative problems and bad experiences where the final film wasn't what they wanted, and I've never had that. If you don't like one of my films, it was the film I wanted to make. I have no excuses. It's not like it was taken away and re-cut or anything like that. It's my own fault. I think I have a good instinct for self-preservation. I can see those train wrecks coming early, and before agreeing to make the movie or casting, just starting down the path... when I'm making a different movie than the power structure around me wants, that's when I just back away. I've been lucky, but I've also been smart about it. I'm also often working on low budgets, where the stakes are kind of low. Paramount barely knew this movie was being made. They have so little money in it themselves. Megan Ellison, who has a company, Annapurna Pictures, she's wonderful. She liked the script and wanted to do it. She has a couple of million dollars in it.

People have complained that an angel investor like Megan Ellison disfigures the economy of American movies by investing in commercially unviable projects...

Private equity money is correcting a disfigured market. That's how creative people have to see it. In my little lifespan I've seen studios change. A studio funded Dazed and Confused. There were no stars in it, at least not at the time. It was plotless, it had nobody in it. They still took a chance. They gave a kid $6 million dollars to make a follow-up to what had been a moderately successful indie film. They liked the script and they took a chance. Studios don't do that, they quit a long time ago. It was a triumph of marketing. The model has been replaced with a data-driven pattern, so you're going to get these big, cartoonish tent pole $250 million movies. That's a better investment for the corporate parents. That's their reality. They've abdicated the kind of films they used to make. They once prided themselves on a slate of films that had a wide variety, and now they pride themselves on making fewer films, all of which are swinging for the billion dollar fences.

How have those changes affected your career?

The big difference is that back then, when I had a hit indie film, all the studios asked me “what do you want to do next?” Now they wouldn't. You have a hit at Sundance and they have a $200 million dollar film for you. They don't want to make your film. That's not their business. I didn't make one of their films until way later. School of Rock was a movie the industry brought to me, and I saw something in it and risked that failure. I enjoyed it and grew from the experience. If that had been my second or third film I would have been doomed. Some people have a hit and want to do something like that and it's their destiny. I'd like to say that something is going to happen and it will shift back. Hollywood movies once got really bloated in the late ‘60s, there were big flops, and then Easy Rider made $50 million and the industry changed. They were looking for youth culture, and we got the American cinema of the 1970s. And then the ‘80s, again, we had these auteur flops like Heaven's Gate and the corporate structure stole it back from the artists. Since then, by and large, it's been on a one-way track. Money dictates so much about the industry. Slacker cost nothing and grossed $1.3 million, which was seen as a big success; they spent a couple of hundred thousand dollars marketing it. They can't afford to think that way now. The Fox Searchlights of the world aren't interested in a movie that will make less than $50 million. It's not worth their time. It's so expensive to let the culture know a movie exists, to break through to young people, to break through the noise. Megan [Ellison] is interesting: I think she's going to start distributing soon. She's very smart, and it's very exciting.

Her name is on a pretty significant body of films over the past few years.

Criticism of her comes from studios who are jealous of having the guts to make the kind of movie you could be proud of.