"...putrid

Infancy,

That can and will forbid

All grist to me

Except devaluing dichotomies:

Nothing, and paradise."

— Philip Larkin, "On Being 26"

“Formal systems of religion lie outside my upbringing and experience, but I find it hard to stave off the sense of intervention that characterizes one’s decline and one’s rise. It is a matter too deeply felt to be a godless act.”

— Andrew Solomon, The Noonday Demon

Colloquially speaking,“love bombing” is a coercive outpouring of support. Marketing teams love bomb customers. Politicians love bomb voters. Sirens love bomb sailors.

But sociologists reserve the term for exhibitions of unconditional acceptance geared toward indoctrination. Military recruiters, for instance, might love bomb a potential recruit—first by emphasizing the military’s exclusivity, then by asking questions that presumably speak to the newcomer’s idealized self-image, implying that he is one of few eligible to join.

The recruiter says, “You can’t be in the military unless you’re very, very strong—like Hercules.” And then, “How long have you had such enormous and impressive muscles attached to your body?”

Cults do it, too. And like any organization eager to enlist worshippers, certain religious groups (especially historically young religions, such as Scientology, born-again Evangelicalism, or Mormonism, whose very existence depends on conversion) will love bomb probable converts by exaggerating similarities between the group and the other, always in a way that promises acceptance and forthcoming exaltation.

In general, such tactics work best on the lonely.

*

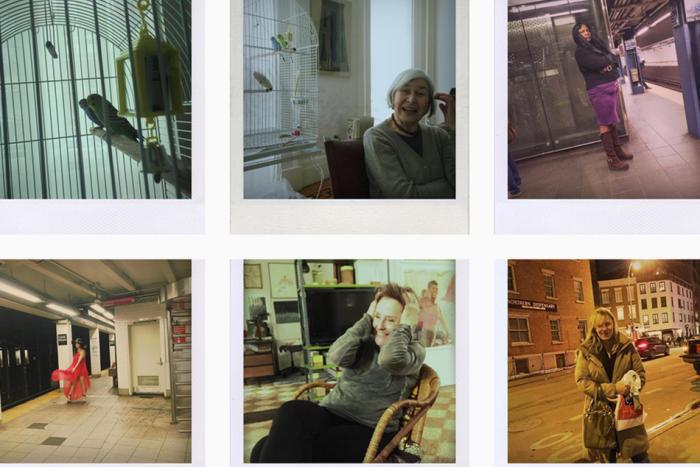

I had never been lonelier. I lived alone, had very few friends, and worked seventy hours a week, for very little money, under the management of a physically affectionate boss named Wally, who occasionally wept in front of me about strained relations with his wife.

Our company was Wally’s brainchild. He’d pitched it to investors as “a newspaper website (a newspaper, except it’s only online),” during a time when newspapers already had websites. His underlings included one full-time employee (me) as well as seven very exhausted, unpaid interns, who I assume (and hope) were independently wealthy because they all went to Sarah Lawrence, which is the most expensive college in the world. We were in a recession. Since graduating college, nearly everyone I knew had already been fired at least once. But acquiring hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans was often as easy as clicking a button that read, "I accept my award!" I felt lucky to have a job.

In general, the interns and I wrote articles that had no real angle, because the site had no niche, which in turn led to an online audience of about 20 or so people, mainly comprised of our parents. It had been funded, like my boss’s ranch house in the suburbs, entirely by his father.

"I’m on anti-depressants, are you? Everyone should be.”

Most days, Wally sat at his desk surfing the Internet, ignoring texts from his wife while the rest of us wrote terrible pieces that answered questions like, “Which bodily fluids can you send via mail?” I often caught him reading his own pieces, published years before, on online newspapers that people knew about. I thought he was very successful. My starting salary was one thousand dollars per month before taxes and the website’s profit margin remained steady at zero dollars. So, to supplement Wally’s slowly dwindling trust fund, the interns and I often jumped on unethical odd jobs for the “tutoring agency” with which we shared a Brooklyn office. The agency charged rich families in the tri-state area two hundred dollars an hour to consult on college applications, and we “ghost wrote” the personal essays for free in exchange for Wally’s office space.

“It has been a month now since the surgery,” I wrote in one such essay, under the byline of a girl who had recently undergone simple Lasik. “Occasionally, I hear my mom’s voice cautiously suggest that we add a few more colleges to my list—specifically, ones with amenities for the blind.”

I got into a lot of colleges that year.

Wally had to be home for dinner every night to eat with his family, but before he left us to our voluntary overtime, he always gave an extremely quiet motivational speech about how we had to keep the ship from going under.

“These projects might keep us afloat—Gupta, Abraham, Pinker,” Wally whispered, looking pale as he listed the names of college-bound, teenage clients we had never met, before slipping away to the elevators. “Please. I don’t want to lose my job.”

His reliance on us, and his perpetual fear of economic failure, made the interns and I feel grown up and important. It never occurred to me to ask for a raise, because I assumed that, if I did, Wally’s family would starve. Late at night, after Wally went home and the tutoring agency people turned out the lights, we talked in the dark, our faces lit by laptop screens, about what an “opportunity” it was to have the freedom to write what we wanted, and put it online—the word “exposure” was thrown around a lot, usually when Adderall was available—and we all agreed that Wally was a great guy for trusting us with his “brand.”

*

To save money I commuted four hours each day from a guesthouse in New Jersey that I’d found on Craiglist. I lived behind a towering, red-brick mansion for almost zero dollars. The guesthouse was the mansion’s miniature twin. Both resembled the dollhouses that I noticed in the cellar one day while doing my laundry.

My landlord was a pleasant-seeming woman named Maude, who liked to garden. She was petite, blonde and spritely, and lived in the Main House with her college-aged daughter, Elizabeth, who was home for the summer. She was more than willing to tell me about herself, which I liked, because often our stories contain secrets, and I adore secrets. I discovered that the mansion and the guesthouse and Maude’s ability to constantly garden had been secured through Maude’s thirty-odd years spent running what turned into a multi-million dollar corporate sweatshirt business, which she’d sold prior to the recession—a period during which few corporations needed swag because they’d all gone bankrupt. I found stacks of sweatshirts in every closet emblazoned with the names of economic casualties.

When I first arrived, Maude said that she and Elizabeth had just welcomed a houseguest named Salina—a former weight-loss instructor who had worked at a fat camp in Hawaii, and now lived in Salt Lake City, where she worked part time as a personal trainer. Maude alluded to the fact that Salina been contracted for the summer to help Elizabeth lose weight. I said I looked forward to meeting both of them. Maude smiled and disappeared inside.

I left early in the morning and returned late, so at first it didn’t seem strange to me that I hadn’t yet met Salina or Elizabeth. After being screamed at by strangers all day to walk faster, to get out of the way, to fuck off—or, occasionally, to go “touch butts with your sister” (shouted at me by a schizophrenic street person), stepping off the commuter train onto the sidewalk of Maude’s chirping, picket-fence little town felt like paradise. I was too intoxicated to harbor suspicion. She provided me with towels and Egyptian cotton bedding. The guesthouse lacked certain amenities, including a kitchen, so she hauled a microwave and mini-fridge into my room. I bought a book called The Adventures of Microwavable Cooking. I used the toilet as a garbage disposal and washed dishes in the gigantic shower in my private bathroom. Usually I took pride in these endeavors. I felt abstemious and handy. Maude welcomed, invited, intoxicated me. She wanted me to call her Auntie Maude.

On the picnic blankets at the edge of the little league fields, Daria asked how old I was.

“I mean, you totally don’t have to say,” she said, “It’s just sometimes I feel weird about not being married, right? And that it makes me feel better to be around you, a little, because you’re obviously older, right? —And you’re not married?”

“Right,” I said.

As the first fireworks squealed and sparked against the starlit sky, she and Salina clapped. My phone buzzed in my pocket. The screen said Restricted.

“But it’s starting,” Salina said, when she saw me stand up to take the call. She shouted to be heard over the fireworks. “It’ll just get better and better.”

“It’s urgent,” I said, and sprinted across the field. Fireworks exploded overhead.

“Magnus?” I said, catching my breath on the sidewalk.

“Hi,” he said.

“Jesus”—it was the first time I’d cursed in weeks—“I can’t believe you really called.”

“Well, I did,” he said. “Here I am.”

“Wait,” I said. “Let me find someplace private.”

I crossed the front lawn of the library, and found a quiet spot behind the building. I slid to the ground, scratching my back against the bricks.

“So,” he said.

“So,” I said.

“The offer on the website, obviously you must know it was a joke, performance art,” he said.

I had not known that.

“Sure,” I said.

“But,” he said, and left it there.

“But?”

“Maybe we could meet,” he said. “But. I Googled you and all I found was this website. This terrible, terrible, needlessly confessional website—and you can’t write about me, okay? — Not about this phone call, not what I say to you, not what we do if we ever hang out—you gotta promise me. Fine?”

“What would we do if we ever hang out?” I said.

He laughed.

“Well?”

“Well, what?” he said.

I sat there picturing him in one of his movies—the large, weird boots, the tight pants. He had off-kilter features.

“Well, what are you wearing?”

“You first,” he said.

I looked down at my outfit. I wore a red t-shirt and mannish navy blue shorts.

“I’m wearing a dress,” I said. “It’s very small—barely a dress. Lots of my body is showing.”

“You haven’t done this before,” he said.

“My body is basically naked,” I said. “And I want you.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah. I want your fucked up, crooked face, and your weird fucking body, and your hands all over me.”

“I like that.”

“Good.”

“What else.”

I pressed the phone to my ear, kicking off my shorts, and said something cliché about how wet I was. The stifled desires of a long hot summer squirmed in my belly. I could hear Magnus breathing. In high school, right before bed, my last minute prep for an exam involved imagining myself fucking whatever teacher was administering it—no matter how ugly he or she was. I reimagined myself shoving Salina into the armchair instead of following her there. Magnus described how, if he were there with me, he’d shove me up against a wall and pull off my little panties. I laughed and told him, “Whatever”—to just keep talking. He said he’d like to grab my little waist and lift me up using only his cock.

Everything up until that moment had felt so surreal and removed; the Mormons wanted my body for God, my boss wanted it for no one, Salina didn’t want to want it—and even with Maude, I felt like her rage, and the body dysmorphia she’d projected onto her only kid, seemed to feed on comparisons drawn between Elizabeth and other girls. Maude wanted to extract from my body whatever made me thin and implant it into her daughter.

But what did I want my body for? Mainly, Magnus’s descriptions of what he’d do to me reminded me that I had one. So I spread my legs in the dirt, and decided the afterlife could wait. Somebody needed to deal with me. Everyone had been giving me blue balls. With just one gravely voice in my ear, I could picture them all.

When I finished, he said, “What about meeting in Manhattan?”

“I might write about this,” I said, dazed.

He cursed under his breath, and a long pause he said, brusquely, “Do me a favor and wait a few years.”

“Bye,” I said.

“Good luck,” he said.

I texted Salina and Daria saying I’d walk back, and returned to the guest house to another note on my pillow: “Again would appreciate”—and then a list of things that Maude would appreciate. Salina knocked on the door. I crawled under the covers and pretended to sleep.

I lay there for hours, replaying Magnus’s deep voice, and scrolling Craigslist for the cheapest New York City apartment I could find. In those desperate, drawn out minutes approaching midnight, I even seriously considered some of the “rooms” that were actually curtained sections of kitchens and included caveats about how rent could be reduced in exchange for “human company."

But then I found it: a disgusting room in deepest Queens, in a crowded apartment with five other people. My room was slightly larger than a queen bed, and overlooked garbage cans. There was a “trigger warning” about feral cats liking garbage. It was $500 per month, with no up front fees.

I quickly called the sweet, nineteen-year-old NYU student, who was so desperately trying to find a fifth roommate in order to avoid more credit card debt that he offered to video chat with me as soon as I emailed him at three in the morning. We met bleary eyed over pixelated windows. He said, “As long as you’re not a serial killer, it’s seriously just fine,” and we agreed I could move in that day. I unpacked the chests, left an envelope for Maude, stuffed my things into a garbage bag, and talked to myself all the way to the train station—practicing a speech for my boss, in which I’d ask for a raise. I faked choked up noises and a sniffy nose. I knew his language, so I would cry in front of him, and it would work.

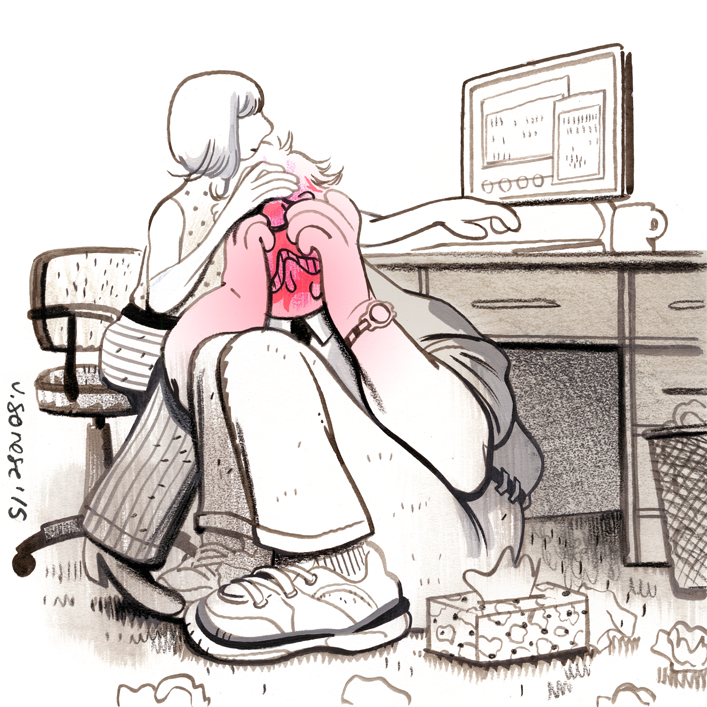

I climbed the train platform feeling exhilarated. The sun was coming up, birds were chirping, and men holding briefcases were smiling at me, and I was smiling back. Being in transit has always made me feel productive and successful—I guess because there’s the assumption that wherever I am going might be better, whether or not that’s true. So I boarded, and I found a spot near the window, and I pulled my knees to my chest, and squeezed. I know why Temple Grandin built her hug machine, because I’ve been on conveyor belts headed for inevitable, unanticipated chaos, but wrapped in my own arms, I have managed to feel safe.

Some details have been changed to protect identities.