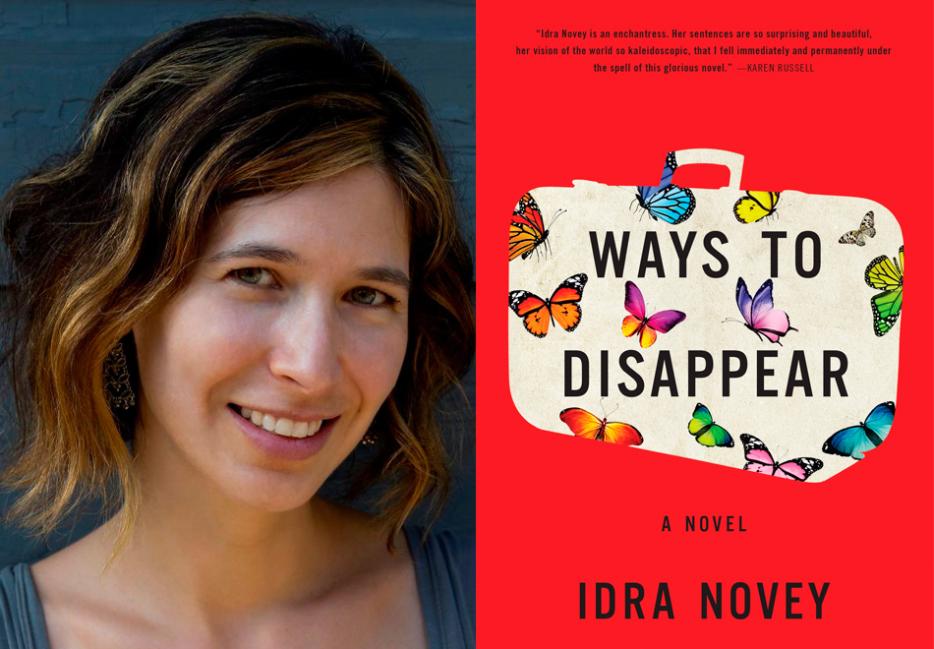

Midway through Idra Novey’s debut novel, Ways to Disappear, the protagonist Emma Neufeld sits at a hotel desk in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, where she’s gone on the hunt for the disappeared author Beatriz Yagoda. Staring blankly at the wall, she wonders if the fear of being useless isn’t central to the modern human condition: “Wasn’t that what Don Quixote was all about?” she thinks.

The allusion to Cervantes’s novel is apt. Emma has been translating Yagoda’s work for years and feels a deep affinity with the author, yet her pursuit of Beatriz, like Quixote’s of chivalry, has gone haywire. Already, Emma has been threatened at gunpoint, and the paparazzi caught her kissing Beatriz’s son before puking over the side of a ferry en route to a tropical island. The author’s daughter has ordered her home to Pennsylvania; instead, she’s followed a far-fetched clue onto a plane and into this hotel room, determined to track down Beatriz’s editor, who may hold the key to her whereabouts. Satisfied that the room is secure, that no one has followed her there, Emma takes out her notebook.

“[Ways to Disappear] is pretty much a novel about a novel beginning in notebooks,” Novey told me when I asked about the scene in the hotel room. I met Novey at a Park Slope café in December to talk about the novel just hours before she boarded a plane to Chile for a yearly trip with her sons and husband. “My notebooks for this novel began with someone writing a novel in a notebook, inside a notebook.” She’d brought some of her notebooks with her to the café—fittingly, all of them were small, playfully sized, and one, her favorite, was decorated with a picture of a bull playing a guitar. She’s had it since 2004, she explained, but used it most recently in 2015—though the middle, as in most of her notebooks, has never been filled. She tends to stop a few pages in, flip it over, and start again from the back. “I guess I like the radical idea of starting again at the beginning,” she explained, of starting again from the point furthest away from where she was. “I think it just becomes habit, to always seek something further.”

This impulsivity—starting over in a radically different place, or grabbing an idea before it gets away—is an important part of Novey’s life and work. If she knows what’s going to happen next while she’s writing, she said, her interest evaporates. Ways to Disappear is written in short, brisk sections, each formally different from the last: emails, dictionary entries, Radio Globo reports, and intersecting storylines. Though the book isn’t without tragedy—one of the characters loses an ear, others die, and others still uncover unsavory truths about the past—the effect is a fun, compulsively readable, consistently refreshing adventure. Much like Novey’s life, it seems: she met her husband on the subway and knew immediately they would marry. She began working on Ways to Disappear while translating Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H., released as part of a quartet of Lispector’s works in 2012, by New Directions; her translating career began seriously while she worked in a domestic violence shelter in Chile. When her sons entered kindergarten in Brooklyn, they spoke only Spanish. This flavor, this taste for the unexpected, is also present in Novey’s protagonist, Emma: she’s a dreamer who gets carried away with her feelings, falls in love easily, craves mystery and suspense.

“The more pleasure for the writer, the more for the reader. Just try to take pleasure in the process. Stand back and ask yourself, ‘Who cares if it doesn’t work out?’”

And always, like Novey, she has her notebook with her. Especially when traveling, the author told me, bringing along a notebook inspires this particular kind of attention—makes her do the “mental action” of immediately translating her experience into language. Some of the notebook entries from 2004, during her travels in Guatemala, made their way into her first book of poems, The Next Country. “This is La Laguna de Lago Atitlan,” she said, pointing to the beginning of one poem. “And this is for the end of the poem,” pointing to another. “This is about translating Paulo Henriques Britto. And this just says, ‘Jeff Shotts, Graywolf.’ Who knows why.” She rolled her eyes; I suggested perhaps she had planned to send him the manuscript. “I think maybe he didn’t take it,” she said with a laugh. “I think it got shot down.”

Novey laughs a lot—a survival skill, she said. She grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania where, as she put it, she was the only one imitating Emily Dickinson in her bedroom at night. “You really can’t be a girl in a small town and be dark,” she said. “They’ll throw you out.” She found refuge in her notebooks and in the theater club, where she began writing and directing plays. Writing represented an escape from small-town anonymity, a reminder that there were other places in the world where she could go, which also fed her interest for other languages. Eventually, she found her way to Pittsburgh, the nearest metropolis, and then on to college at Barnard, where she majored in comparative literature—and also where she began translating. Her sophomore year, she turned in a translation of a Rosario Castellanos poem as an exercise for one of her classes, and her professor recommended she send it out for publication. Soon after, another professor began asking her to review books in translation for Review: Latin American Literature and Arts. “It really means a lot to have a professor say, ‘I see you can do this,’” she said. “It’s so pivotal.” She does the same for her students at Princeton.

Since then, she’s translated four books from Spanish and Portuguese, most recently The Passion According to G.H. For her, translating an author is like getting to know a character. “In the same way, as a novelist, you think, ‘What would my character do here?’” she said, “as a translator, you think, ‘Why is my author doing this? What was the motivation to write the sentence in this way, and leave this unsaid?’” Her Sylph Editions Cahiers Clarice the Visitor, a collaboration with the artist Erica Baum, was a way of conversing with Lispector during and after The Passion According to G.H. went to print. Novey felt she needed to resolve inwardly certain unresolvable aspects of the translation as it was being released. “I wanted to talk to her on my own terms,” she told me. Similarly, Ways to Disappear was a way of continuing the conversation with Lispector, with whom she had come to feel a real intimacy. Beatriz Yagoda does bear a certain resemblance to Lispector, and Emma Neufeld’s pursuit of the author very much relies on her ability to decode Beatriz’s cryptic clues as they arise in her writings. “I was thinking about the way you can know, and also come to un-know, an author,” Novey said. “The author that you get to know in one book is not the author that you get to know in another book,” nor is a translator the same from one book to the next.

"There’s something appealing about burning shit down."

Or even from draft to draft. It took Novey five years to finish Ways to Disappear. In between, she was teaching and translating, and writing poetry. Often, she would return to her manuscript after a period of time away and see that certain things she had thought were true about a character weren’t any longer, or that a scene she thought was essential was unnecessary. “I think it made me braver to get away from it,” she said. “If you’re in a book and you never take a break from it, it’s inhibiting.” Her editing was ruthless, and that’s a good thing—the book moves at a clip. There’s a madcap feeling about the way Emma follows omens: a secret letter, a feather, a vague memory, an accidental tip. Novey’s reality is slippery, with magical realist overtones—it’s another way she’s risked failure in her lifelong quest to escape Appalachia. She spent twenty years feeling melancholy, she said, and now would rather chase feathers in imaginary worlds. “I think, the more pleasure for the writer, the more for the reader,” she said. “Just try to take pleasure in the process. Stand back and ask yourself, ‘Who cares if it doesn’t work out?’” Courting failure is essential to her writing, and failure is intrinsic to any finished work. “I think there are things that you can’t reconcile and they’re always the most interesting things,” she said. “The untranslatable, I think that’s the most subliminal part.”

Novey worked on Ways to Disappear for a month in Chile while brush fires rolled on the hills around the ranch where she stayed. She was writing and the air was full of ash; it was floating on the pool and in the dog’s water, and sticking to the leaves of Novey’s salad at lunchtime. People in the house took turns talking to the volunteer firemen and the neighbors, not knowing if they’d soon have to evacuate. They put water on the roof of the house. They slept knowing the fire could reach them during the night. Descriptions of ash ended up making their way into Ways to Disappear, as Novey sat watching the fire on the dunes as she wrote. To anyone acquainted with Lispector’s biography, the fire in the novel recalls the one that mangled her hands one night when she fell asleep holding a lit cigarette. But it also reflects Novey’s artistic philosophy: “There’s something appealing about burning shit down,” she said, comparing it to flipping to the back of her notebook. She’s courting failure every time she writes. “If I don’t want anyone to know how badly something went,” she said, “I just set it on fire.” Then she starts over.

Paper Trail is a monthly column exploring the relationship between artists and their journals.