Four horses that weren’t friends but knew each other slightly—from other horses and from the local pasture scene—all took a job one afternoon because, as they explained it to one another, they sort of had to. None were lazy, but neither were they motivated, gifted, or blessed with any particular spirit. They were just horses, well-muscled; vain; bored.

“What do you do outside of this?” asked the first horse, a guy with a black, sensually lank mane that he flicked hither and thither. “I have one or two projects on the go,” said the second guy horse, his left eye bulging.

The third horse (more auburn than chestnut, she thought) wasn’t into the conversation, so she moved towards the fence and thought about her ex, who she’d heard through a literal grapevine was—this very afternoon—taking the farmer to town. She resented this small success of his, and now fed that resentment with recollections of his personal flaws. Ew, she thought. Hate him. Lately, the third horse had been taking on as much freelance work as possible, hoping to buttress her faltering ego with a sense of purpose and wages. Still, she was tired, and when she was tired, she got edgy, and when she was edgy, she wondered if she had ever known love—if love was even a thing. More urgently, the third horse wondered why so frequently she thought of eating meat. Seemed… weird.

The second horse, the one with the delinquent eye, had heard things about the first horse (sexually) and was thus surprised to see that his dong wasn’t really that big. Somehow, this made the first horse even more impressive. The other two seemed fainter—the third and the last—maybe because of their lack of sexual cachet; also, the second horse couldn’t defer to women, much like he couldn’t make his eye stop pulsing hotly in its socket. Ultimately, he just felt more regard for the first horse and his whole thing.

The first horse moved slowly but decisively from the second horse. The second horse noticed this, and as if magnetized, traveled the feet required to maintain precisely the same measure of grass between himself and the first horse.

The weather was fine for late September, air abuzz with dragonflies and fragrant with different kinds of shit. The second horse felt giddy but odd after his brief exchange with the impressive first horse. Watching his shining haunches, the second horse admitted to himself that where he was in his life right now did not exclusively define him. So what if he didn’t have any particular projects “on the go,” as it were? That didn’t mean he was any less of a horse—any less “invested” in his soul’s work than the next mindfully castrated gelding. Abruptly, the second considered the feminine aloofness of the third horse; taking in the rich distance that made her attractive in this moment. The third horse noticed the second horse staring and flicked her tail twice, which could’ve meant either interest or disinterest. The second horse was not great at understanding female behavior. It was likely disinterest, which was basically the story of his life. He pretended to graze.

As the second horse nosed the ground, the third horse thought about how good the word steak sounded; how it near sizzled in the great barbecue of her mind. The first horse squinted at a distant silo, upon which sat a bird of no distinction. The bird made a very small noise, its beak shearing apart.

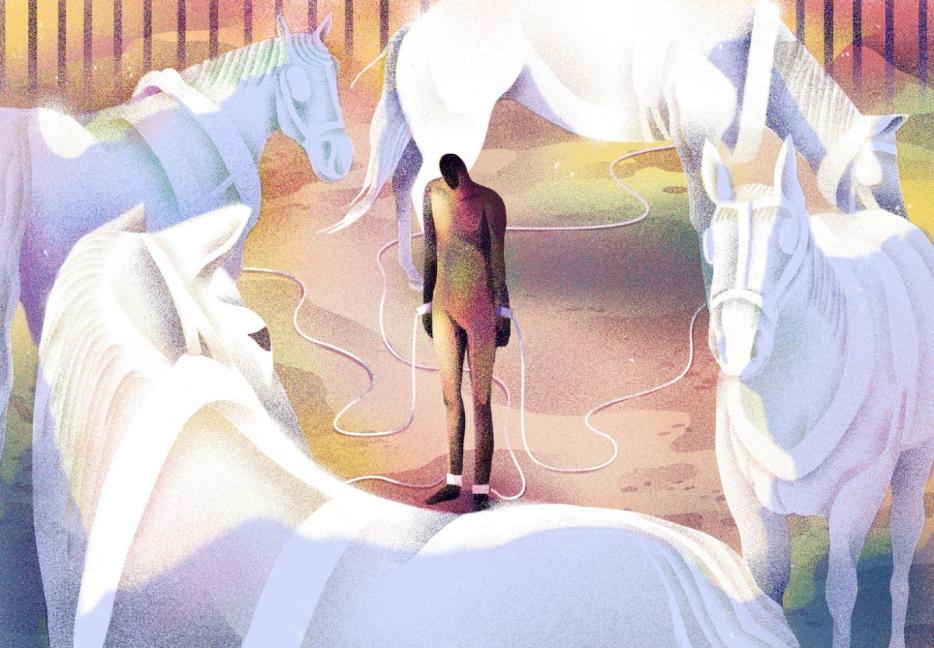

The first, second, and third horse paid little mind to a lone man nearby, his body crossed with chains that jingled as he dragged a twig around the dirt where he was fettered. Behind him stood a few trees that, after a few yards, thickened into forest. In this forest, glossy needles blanketed the floor, the green canopy above shot through with sunlight. Once or twice, the man labored to peer into the heart of the forest, twisting against his shackles, hot as a brand.

The last horse had been trying in vain to keep occupied, for he was high-spirited and didn’t care to be penned. Taking note of the jingling and scraping man, he perceived a diversion. Sashaying over, the last horse tossed his mane so the breeze caught it in ripples. He was flirting, because humans sure did love to flirt. Confidentially, this sort of bothered the last horse. Since foalhood, he’d been considered a pretty horsey. But that was because his people were thought to be beautiful, as confirmed by the widely held love of horses, felt, for instance, by young girls and olden times folk—many of whom had wealth and knowledge of trousers. So the last horse was aware that it was a categorical beauty, and that he didn’t have anything exceptional going for him. He was more or less a horse, one that people might admire were they to see him running alone in a field, or fulfilling some other cliché of his kind. (He did have a gleaming white streak down his nose, which made him a little bit unique.)

Humans were cavalier towards him, and in light of this, he had cultivated a series of affectations: lip blowing, heavy-lidded glances, an unnecessarily bouncy canter. The other horses despised it. But humans really dug it, and he liked humans more than horses when humans were around. It made sense to have a personality sweetened for humans. Thus he left the regular company of the other horses to address this truthfully shabby-looking man chained to the ground with nary a sugar cube in sight. To the last horse, he just seemed cool.

He stood before the man and breathed forcefully through his nostrils. The man lifted his head to see the long nose undulating inches from his face and recoiled, it seemed, voluntarily. The last horse was offended, (he was quick to offense), but considered the possibility that he had come on a little strong. So he stepped back a bit and eased off on the eye contact. The man looked at him less warily, but didn’t reach his hand out, which was the universal gesture. Besides the various clanking things, the man was wearing a rough sack, full of holes and cinched with twine. Running through the folds were thousands of lice, calling out to one another in high, grating voices. The last horse wondered if they bothered the man. They would, he knew, bother him a great deal.

Throughout this, the first horse had been feeling impatient, the impatience now piqued watching the last horse involve himself with the prisoner. He was one of those horses who felt more comfortable—or maybe less uncomfortable—watching other horses be horses; always a little off-kilter when he was in the fray, being a horse with other horses. Sometimes he felt bitter watching the other guys in his community hang so casually with each other. It seemed that they could share a mutual focus with such ease, an ease that kept him vexed—he who felt outside, always on the outside of things. This made him very attractive to women, which he was only half-aware of. But being half-aware was all one needed to bone a lot of mares.

The first horse assessed the man with distaste. He didn’t like human people, flabby and jointless as they were. They appeared to be perpetually on the verge of some small ruin. Horses were made of gristle and bone; they were capable of a physical strength that humans could only dream of, harness, and occasionally dread. The first horse was excited now, because he was driven by purpose and function foremost, and looking at the man and the last horse, he anticipated the work to come with a glimmer of satisfaction. Feelings lived within him like small farts and were released with as much frequency. He struck the ground with a front hoof and watched the dust rise.

What all four horses knew to some degree was that this man, currently being teased and charmed by the last horse, was maybe a thief or a radical or simply wrong-headed. Whatever his crime, those locks and chains trailing from the neck, wrists, and ankles rendered him opaque. He lacked the observable spectrum of human feeling that, confusingly, allowed humans to describe anything with emotional texture as “human.”

But the man had loads of feeling surging within him. Sometimes it radiated from the heart or gut, sometimes it pulsed in the divot at the base of his skull. Occasionally it stirred in or near his groin—although that wasn’t happening so much today. In fact, for the first time in a good many years, the man was thinking about concepts and stuff, such as: family, which he didn’t really understand, but now found himself considering with unprecedented patience. What was a family, even? What was it to be a single thing, born unto a group who may or may not care for you, who might leave you to die, or worse yet, prime you to live in a harmful and graceless way? To live a life without honour, without boundaries or respect for the law (both personal and made up). Family and neighbors who taught wrong ways in a world that gave lessons roughly, with pain and punishment. The man felt a cool clearing in the front of his head, between his eyes. He had been born for punishment.

“Punishment is indivisible from my character,” he told the last horse, who understood this to mean that the man was a professional actor, how cool.

So the horses waited and the man waited and the sun did its thing and everyone felt at peace. Well, not the man, who’d dither quasi-peacefully before snapping back to a terror state. He stank of fearful perspiration—of old metal fixtures and a multivitamin-esque sweetness that the horse nuzzling him didn’t seem to mind. These were pleasure smells.

As the sun lowered, another man crested the hill overlooking, a long-barreled shotgun resting on his shoulder. His face was creased and spotted but still fine to look at. This is what women in town felt, even if they didn’t say it. They didn’t say it, because to say it would invite rape—not from him precisely, but because it was a known incantation that brought rape down on those who said it. So they didn’t say it and avoided rape. Mostly.

Having prepared everything to his satisfaction, the second man now led the criminal into the forest, the new moonlight blocked by the trees’ bottle-brush density.

The second man stood at the brink of the wood and shook his hand in front of him, which made all four horses turn from their various attentions. They approached him lazily, not wanting to seem too eager. Nosing the hand, they discovered carrots, a little soft, maybe, a little shrunken within themselves like a boy’s tiny penis; but carrots. They followed the man into the forest, chewing.

Quickly, the horses were positioned crossways from each other in the clearing. You could draw a line from one horse to its opposite, forming an x. The second man attached a thick chain to a harness on each horse’s back, pulling each chain into the centre of the clearing. Now the chains did, in fact, form a sprawling X. This was integral to the bylaw, and all of the heritage codes—aesthetic standards. The second man took great care with his legacy chains and harnesses, which had belonged to a whole bunch of fathers who may as well have been his.

The third horse shook a bit to find some comfort within the chafing throatlatch. These shit bridles, she thought before fixing her eye on the ground. She was watching an ant, frenzied and harassed by a larger bug with glassy wings. Get him!, she thought. She truly did hate these bridles, and the electrodes taped to their necks. They itched like hell.

The second man had rigged the four horses to a beautiful metal-and-leather harness that he was now fitting on the first man. Although he didn’t whistle or hum, the second man had cultivated an amiable expertise that allowed him to be completely blind to what the first man (and other men who had been, and would be, in the first man’s position) was experiencing. In any event, there was no witness to the first man’s feelings, his subtle behaviors, his special tears containing the salt one’s ducts saved for such an event. The second man smelled urine, which was a normal smell in moments such as this one. It reassured him.

Above the horses’ heads, the sun set discreetly. Nothing to take a picture of the way you might a certain, profound sunset. The second man reached into his small pack and withdrew a remote control, blunt-edged with one concave button in its center, molded to receive the thrust of a human finger. He reviewed the checklist he’d taped to its underside many years ago, too many to count, ruddy water stains blooming at the paper's edges. Long ago, a horse quartering would have required a team of men, not to mention the cruelty of whips. Now he could run them independently thanks to a few second-hand defibrillators bought for song. In the dimness, he marked the five shapes before him, then pressed the button.

Electricity coursed through the horses’ bodies, causing them to tense, rear, and charge in opposite directions. The chains squealed and tightened until brutally taut, sparks etching the darkness. Within the sound of hooves, high screams rang the air—peals of a human bell. And then quiet. The chains snapped and slackened.

The man entered the clearing, using his flashlight app to assess the cleanup. The horses lay in the grass, dazed and neighing. He unharnessed the first, second, and third horse, peeling tape from the electrodes and dropping them into his vest pocket. The horses raised themselves on shaky legs before gathering at the perimeter. Moving to the last horse—slightly smaller than the other three with a bright white bolt along its nose, the man saw that this horse’s back leg was shining with blood, shattered bone piercing the flesh. He saw too that the horse was shaking, emitting sounds choked with despair. Flecks of white clung to his lips and his mane quivered in the pinprick light. The recoil had sent a rusted shackle whipping back in the direction of this horse, striking his tender shin. The other three horses clustered on the brink of the clearing, watching sidelong as the man took stock of the situation. The last horse’s ears lay flat against his head, eyes bloodshot and gleaming. He liked humans, humans had always shown him kindness, especially when he flirted.

The man met the waiting horses and gave them each three lumps of sugar, which they gripped between their rank teeth. Turning from the clearing, the horses ambled back through the darkened wood towards the pasture on the other side, where they would make their goodbyes and follow up on individual plans. The sugar was sweet on their teeth and the air held many promises for young, healthy horses. They would run through the night, hooves thundering.

As he watched their swaying haunches disappear into the trees, the man pressed the dustings of sugar between his fingertips, working them into the calloused pads. He walked back to the last horse, whose head now lay still on the black ground. The man held his fingers to the last horse’s mouth, felt his tongue accept this paltry remuneration, taken and spent in the same moment. His fingers now clean, the man raised himself to standing and took a pistol from his belt. The shotgun would’ve made a mess.

Happening to glance at the moon, the man saw a small bird flicker in silhouette before it, which, he knew, was a rare thing to see.