In December 1949, the Franco regime sent four Spanish poets to Latin America as emissaries of what it called a “poetic embassy.” Their mandate was to share their work, the literary fruit of Spain’s National Catholicism, with their Spanish-speaking brethren on the other of the side of the Atlantic. The four poets saw their trip as good-hearted cultural diplomacy, a handshake across an ocean, while the many detractors they would encounter during four eventful months abroad saw only the invasive political propaganda of a foreign dictatorship. The success of the trip, much like a poem, was also open to interpretation. A poet who declined at the last minute to participate in the trip later called it a “rotund failure,” while the regime would spin it as a triumph, in spite of the fact that it ended abruptly because of a political assassination. And yet it was another assassination, carried out more than a decade earlier in dramatically different circumstances, that truly defined the trip—the murder of the poet Federico García Lorca.

***

While all four poets came from the victorious Nationalist side of the Spanish Civil War, they weren’t a political monolith. In fact, they were a good reflection of the varied right-wing coalition that had united to defeat the Second Republic, a grab-bag that had included everything from die-hard fascists, to wealthy aristocrats, to Catholic traditionalists. The oldest member of the “embassy” was forty-three-year-old Count Agustín de Foxá, an aristocratic bon vivant and the author of Madrid de Corta a Checa, a novel about a young man’s conversion from right to left during the war. A diplomat posted in Argentina, he was also the biting wit of his generation, known for his celebrated mot, “I’m a count, I’m fat, I smoke cigars, how am I not going to be a right-winger?”

Foxá’s complacent, privileged conservatism contrasted with the earnest fascism of thirty-three-year-old Antonio Zubiaurre, a poet and editor who had fought in Russia alongside Nazis during World War II as part of the Blue Division of volunteer soldiers Franco had sent to fight Stalin. Then there was Leopoldo Panero, forty, who had been a communist poet before the outbreak of the war, and friends with such leftist poets as Pablo Neruda and Miguel Hernández. After being imprisoned and narrowly escaping execution by the uprising, he enlisted in Franco’s army as a soldier in order to survive, only to end up being seduced by the mystique of the Falange, Spain’s fascist party. When the trip to Latin America came together, he had just published his first full-length book of poetry, an earthy paean to traditional Spanish values such as god and family.

Lastly, there was Luis Rosales, Leopoldo Panero’s best friend since the early 1930s, whose life had also been reshaped by the war. Rosales came from a conservative family; he had joined the uprising from its beginning. Yet in spite of their political differences, Federico García Lorca had been his poetic mentor and friend from long before the outbreak of the war. They were both from Granada, and when rumors began stirring in the city in August 1936 that certain local adherents to the rebellion had it out for Lorca, the Rosales family sheltered the poet. This secret soon got out—allegedly one of Rosales’s brothers informed members of the local rebellion—and made its way to just the wrong person: a vengeful would-be politician named Ramón Ruiz Alonso, who hoped that by erasing Lorca he could buoy himself to higher status in the Falange. With a force of nearly one hundred soldiers, he surrounded the Rosales home and demanded Lorca come out from hiding. The poet was hauled away to jail, only to then vanish.

Luis Rosales protested at the military headquarters in Granada, causing a commotion that nearly put his own life in danger. He was sent to the north for the remainder of the war, where he edited a fascist literary magazine and oversaw other literary propaganda. Lorca’s death would leave an indelible mark on Rosales, as it would on the trip to Latin America with his three fellow poets.

But before anything else, the men had to leave Spain, which was easier said than done.

***

On the morning of December 6th, 1949, the freighter Habana of the Transatlantic Company was preparing to voyage across the Atlantic. But there was a problem. The ship was leaving at mid-day and Leopoldo Panero was nowhere to be found.

After setting off a few days earlier from Tarragona, in Catalonia, the Habana had docked in the city of Cadiz, on the southern coast of Spain. Panero and Rosales, taking advantage of this stopover, met up with a group of old friends and launched a bender of epic proportions in nearby Jerez (a city famous for its sherry), drinking themselves from lunch one day until morning the next. Along for the ride was José Caballero Bonald, a twenty-three-year-old aspiring local poet, who had felt a sense of privileged awe the day before when he had been invited to join. Now, with the freighter threatening to unmoor and leave Panero behind, he was part of the search party. Fifty years later, he would recall the crisis and its denouement in his memoirs:

After fruitless inquiries, the conclusion was arrived at that possibly he had been held up in a brothel where we had landed late into the night. And there he was, in effect, not in any bed nor in a presumable state of intoxication, but given over to the painstaking delight of a bath. The scene had something of the burlesque to it. Submerged in a washtub, with water up to his waist, Panero remained in a state of ecstasy while two girls of the house judiciously lathered him. When he saw us burst into the bordello—which enjoyed, as wasn’t rare at this time, a certain domestic simulacrum—he raised a stink and refused to leave that place where he was so richly taking pleasure.

Rosales finally convinced Panero to get dressed and they raced back to the port just as the crew was preparing to retract the gangplank. Caballero Bonald, who didn’t get a chance to say goodbye, watched the men go, disillusioned by what he had seen. “My naïveté resisted admitting that those two famed poets were just simple mortals entangled in the most ordinary mess.”

The Habana steamed off toward its namesake port across the ocean, in Cuba.

***

The trip had come about thanks to Panero and Zubiaurre’s former boss at a Francoist thinktank, who was now the Spanish ambassador to Peru. He had convinced the General Directorate of Cultural Relations in Madrid to pony up the money for the tour, which would last three months and include stops in over ten Latin American countries. What no one quite understood at the time was the unique and precarious inflection point in history the four Spaniards were traveling into.

The Spanish Civil War had been an emotional, bitterly divisive event not just for Spaniards but for people around the world. It had also been the most literarily dramatized conflict in modern history. As Pablo Neruda would write in his memoirs, “In the history of the intellect there has not been a subject as fertile for poets as the Spanish war.” Ernest Hemingway published For Whom the Bell Tolls and W.H. Auden published Spain, just two of many works by non-Spanish writers that cemented the conflict in the global imagination. Meanwhile, the Spanish writers who managed to survive the war and its aftermath—which, along with Lorca, took the lives of the legendary poets Miguel Hernández and Antonio Machado—fled into exile, most landing in Latin America. Although the Spanish Civil War had ended over a decade ago, memories of its mythic narratives and the nearly half a million lives lost remained strong in the region, especially among leftist governments. Yet its legacy and that of World War II were, geopolitically speaking, giving way to the new rules of the emergent Cold War. The world’s democracies had ceased to position themselves in opposition to fascism, and instead to communism. Yet many communist governments were still fixated on enemies like the Franco dictatorship, since the United States’ heavy-handed interventionism in Latin America was still a few years away.

The four hapless Spanish poets found themselves in the crosshairs of this transition. They knew how horrible their country’s civil war had been better than anyone abroad—they had all lost loved ones on both sides of the conflict—but they hoped to heal the wounds of the past through literature. This was especially true of Panero and Rosales, who weren’t Francoist fanatics so much as survivor opportunists. As Panero, a longtime admirer of Latin American poetry, wrote, “We were burning with purity, like a boyfriend who holds, for the first time, the hand of his girlfriend.” The four poets were unprepared for what awaited them.

On December 16, the Habana made landfall in the New World—in Hoboken, New Jersey. They were both far from Spain and painfully close, especially Rosales. After the civil war, the Lorca family had emigrated to New York City, where the poet’s parents, brother, sister, and their families had made a new life for themselves. While the Rosales and Lorcas had been friendly in Granada, now the past divided them. The poets knew how close the Lorcas were as they wandered the Hoboken port, but they didn’t visit them—not yet.

The poetic ambassadors arrived in Havana just before Christmas and stepped onto the quay. To welcome the Spanish visitors, the leftist press rained down colorful insults: crooked hacks, typists of the Falange, trained amanuenses of Francoist propaganda. At the same time, a handful of prominent Cuban writers came to their defense, such as Dulce María Loynaz.

At the dawn of the 1950s, Cuba was whipping left and right. The Soviet Union had opened an embassy in the country in 1943, while American-owned companies invested heavily in the small yet lucrative Caribbean island. Meanwhile, the characters who would unleash the Cuban Revolution a decade later were already converging. In 1948, a twenty-one-year-old Fidel Castro had been in Bogota, Colombia, when the liberal presidential candidate was assassinated, setting off riots in which he participated. That same year, Cubans elected Carlos Príos Sacarrás president, the man dictator Fulgencio Batista would overthrow four years later, who ruled until Fidel Castro in turn overthrew him.

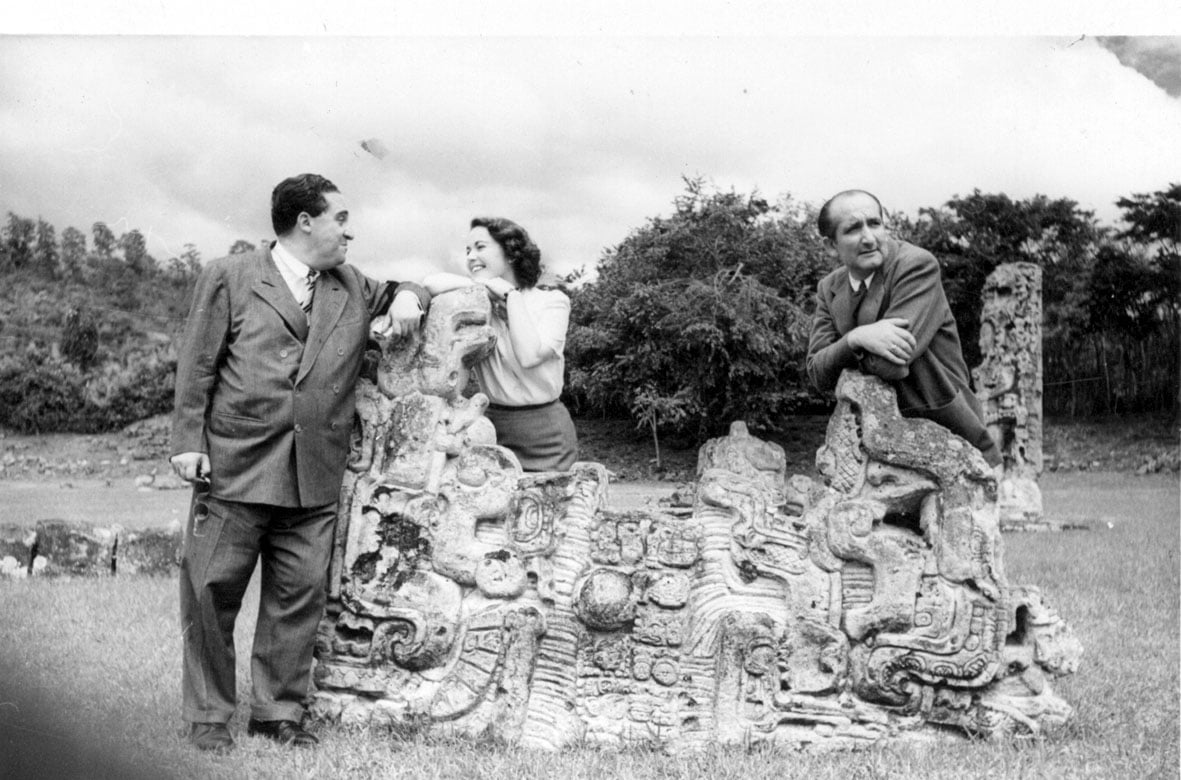

Agustin de Foxa, the daugher of a Spanish diplomat, and Leopoldo Panero at the Mayan Ruins of Copán in Honduras.

On Christmas day, the four poets gave their first reading at a civic organization in Havana. Yuletide warmth did not envelope them. Their verses were met by antagonistic whistles from the crowd, followed by airborne eggs. Panero narrowly dodged the ones that came flying his way, only to watch them explode next to him against the Spanish and Haitian ambassadors. Foxá wrote to his mother about the incident, “Communists tried to interrupt…but they were detained and beaten, mainly by Spanish priests and friars, who acquitted themselves heroically.” The crashers of the event were protesting against writers from a fascist dictatorship coming to their island to share their work, but they were especially after one person: Luis Rosales.

All throughout Latin America, rumors abounded that, rather than trying to save Lorca, Rosales had been the Brutus to Lorca’s Caesar. As one Cuban newspaper had reported in anticipation of the poets’ arrival as they were still crossing the Atlantic: “Luis Rosales, the ringleader of the mission, was the traitor that deceived the good faith of García Lorca so that he would hide in his home in Granada, from which he took him days later to turn him into the firing squad.” According to Rosales’s son—also named Luis—in the face of these attacks both written and airborne, the poet sent a message through the Spanish embassy in Havana to Lorca’s father, Federico García Rodríguez, asking him to write a letter vouching for his innocence in Lorca’s death. Allegedly, Lorca’s father obliged, though after giving the letter to the Cuban press, Rosales would discover that he should have requested a letter for nearly every country they visited.

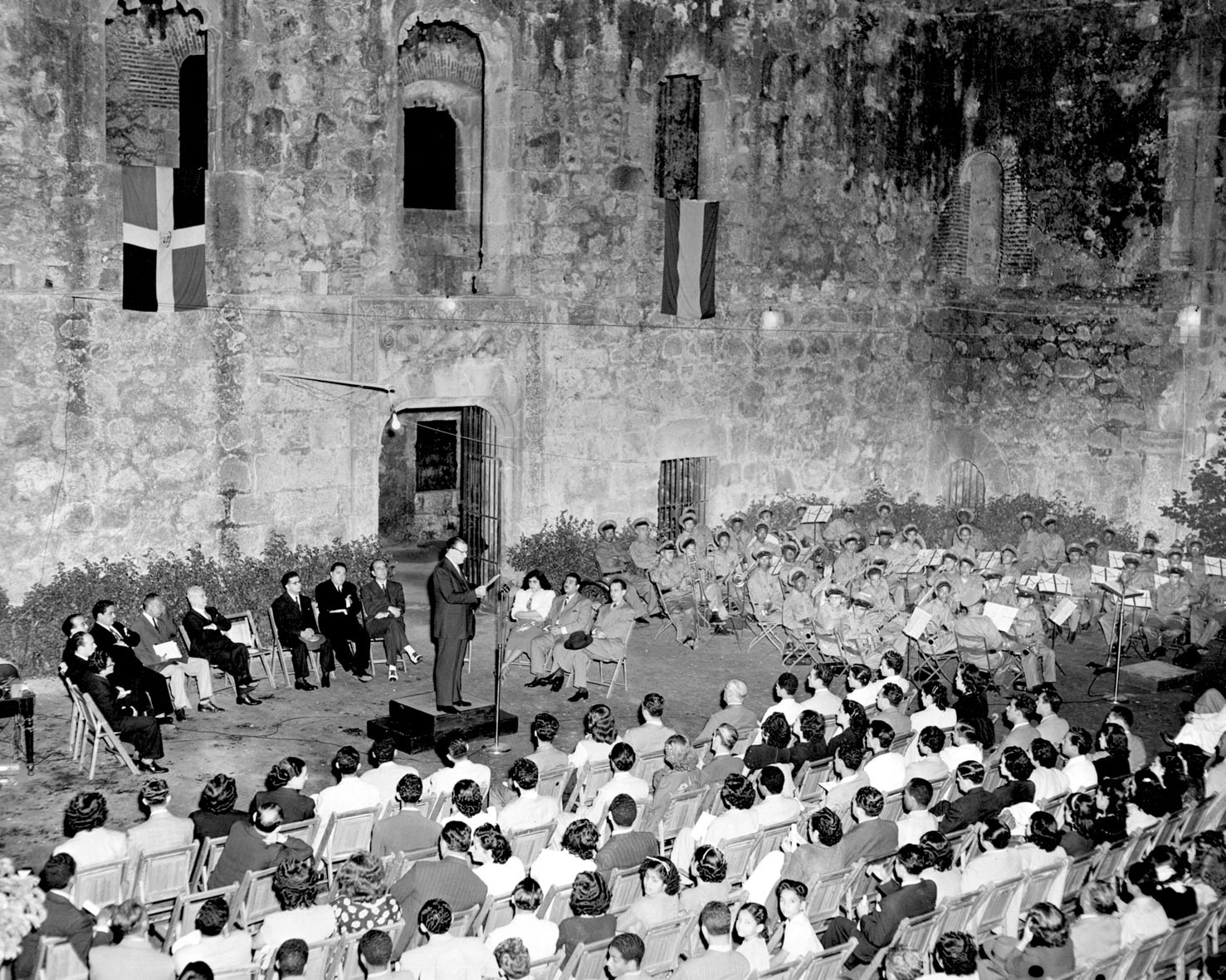

Despite the contretemps that marred the poets’ first public appearance, they triumphed in other, more receptive venues in Cuba. Before the end of December, their itinerary pushed them onward. The group split in two to cover more ground. Zubiaurre and Foxá went to the Dominican Republic, while Panero and Rosales traveled to Puerto Rico, where they rang in 1950. On New Year’s Day, Panero sent a letter to Rosales’s wife back in Spain that began, “Don’t be afraid.” He wasn’t just offering empty comfort. Puerto Rico was more welcoming than Cuba, as was their next stop, the Dominican Republic, where the four poets reunited. They read to large audiences. While in the Dominican Republic, the men met with Cipriano Rivas Cherif, a Spanish playwright who had been a diplomat for the Republic, only to spend years in Franco’s prisons after the war and narrowly avoid a death sentence. War had once defined them as enemies, but it didn’t prevent this reunion, a nuance of the civil war’s legacy the protesters against the four poets likely didn’t grasp. Both exiles and people who stayed in Spain had lost so much, yet many still retained affection, or at least openness, toward people who had ended up on the opposing side. Now it was as if a familial bond from the lost paradise of the pre-war years transcended divisions, allowing former enemies to fleetingly act like friends again. But such nostalgic encounters were brief. From the Caribbean, the poets continued on to Venezuela.

Like Cuba, Venezuela proved a touchy destination. The year before, a military coup had upended three years of democracy and installed a dictatorship. A dissident movement remained in the country, however, and activists showed up at the poets’ reading in Caracas the second week of January. The Spaniards knew there would be demonstrators but were reassured that things would be kept under control. They weren’t. As soon as the event commenced, someone cut the power to the building. In the dark, eggs and tomatoes splattered around them. Gunshots rang out. The poets rushed off the stage. As in Cuba, the primary target was Rosales, who, as Zubiaurre later recalled, “felt intimately hurt.” After they had escaped the melee, Foxá tried to make light of the near-riot with his customary sardonic banter: “We’re going to have to go around with a banner that says, ‘The killers of García Lorca greet their fans.’”

Colombia, on the other hand, was an altogether different story. After the violence the previous year, the president had squashed his liberal opponents, and the climate that awaited the poets was enthusiastic. During twenty days, they packed in nonstop readings, with the press calling their tour “an unprecedented success.” The poets met with more Spanish exiles, including an ex-minister of the Republic, then moved north to Panama, where they read for an audience of two thousand. From there it was onto Costa Rica: ovations at one venue, eggs at another. (“They have a marked affinity for omelets,” Foxá quipped to his mother.) Next, Nicaragua, where the Somoza family ruled over the country. They were treated like visiting dignitaries everywhere they went. In spite of its inauspicious start in Cuba, the “poetic embassy” had turned into such a success in the end that the Directorate back in Madrid wanted to extend their itinerary. A Spanish diplomat, José Gallostra, was doing the tricky advance work sorting out their visas to visit in Mexico, which refused to recognize the Franco government.

A poetry reading in the Dominican Republic.

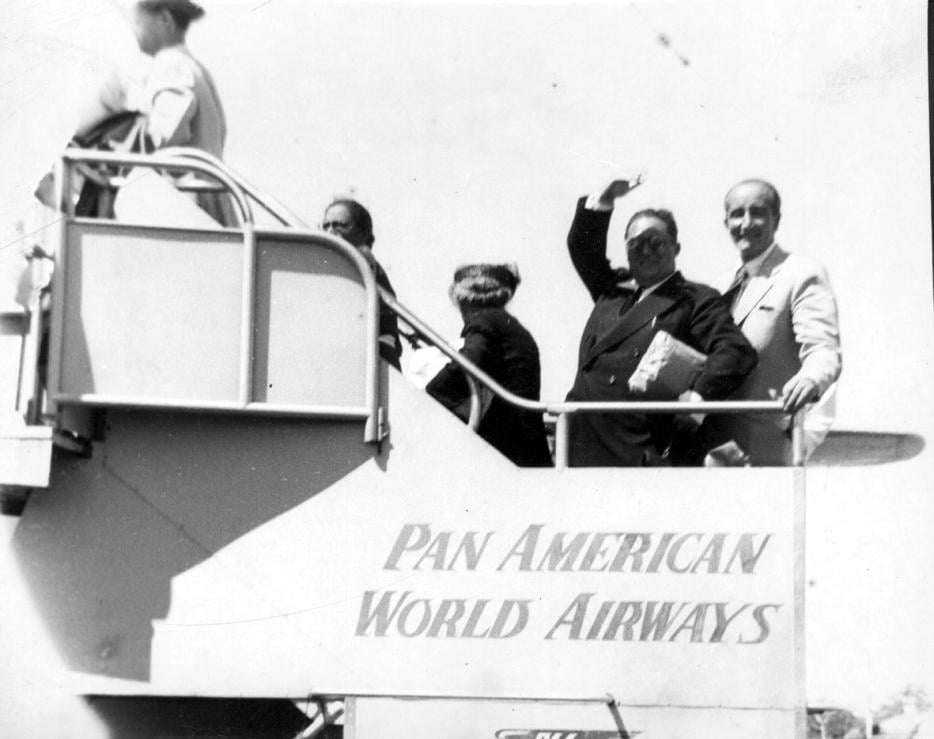

After returning to Havana, the four poets prepared to fly to Mexico. From there, they would continue on to the United States with new stops added in the American south. All the heat and travel and long days, though, was wearing on them. At some point, Panero and Zubiaurre, both known for their tempers, stopped talking to each other. In photos from the trip, the four Spaniards look haggard and under-showered. Then they received shocking news.

The Spanish diplomat Gallostra, who was arranging their trip, had been murdered in broad daylight outside his office building in Mexico City. Two point-blank shots to the head “as midday crowds jammed the Paseo de la Reforma,” reported The New York Times. The assassin was a Spanish exile, anarchist, and former soldier for the now vanished Second Republic.

The killing of Gallostra and the ensuing diplomatic debacle prompted the Spanish government to discreetly wind down the trip. In Mexico, the four poets quietly boarded the steamer Magllanes bound for New York City, their final stop before setting course for Spain.

***

“Extra human architecture and furious rhythm,” wrote Lorca of New York, where he briefly lived in his twenties, inspiring his famous book Poeta en Nueva York. “Geometry and anguish.”

Indeed, it was a strange, painful geometrical alignment of politics and poetry that had brought the poets to New York, where they arranged to meet with members of the Lorca family, who still carried with them great anguish amid the skyscrapers and noise that filled the city. They had put an ocean between themselves and the homeland that had taken their son and other loved ones, but Spain now appeared in the form of three men who hadn’t been forced to leave like them: Panero, Zubiuarre, and Rosales. (Foxá had returned to his diplomatic posting.)

They met at a café in mid-town Manhattan. According to Rosales and Zubiaurre, the reunion was warm and cordial. Federico Sr. was present, as was Lorca’s brother Francisco and his wife, Laura de los Ríos (who, as it happened, Panero had been unrequitedly in love with in the 1930s). Rosales gave Lorca’s father papers belonging to his son, and Lorca’s father asked Rosales to help sort out an issue related to a piece of land he still owned in Spain. Yet Francisco and Laura’s daughter, the niece who never got meet her famous poet uncle, later heard a different version of the meeting. “My mother told me years later that it was a tense and upsetting encounter,” she recalled, “but didn’t say anything else.” Perhaps the uncomfortable ambiguity of Zubiaurre’s account best captures what transpired as the Spaniards spoke in the city Federico had immortalized, a world away from the country where they had all been born: “I have the very firm feeling that Lorca [sr.] didn’t consider Luis [Rosales] guilty of anything,” Zubiaurre said. “Of course, he considered him an enemy, but an enemy from the war, nothing else.”

An enemy from the war, nothing else—a more incongruous positive assessment of a relationship is hard to imagine, as if the Spanish Civil War hadn’t been an epic fratricide, but rather an unfortunate misunderstanding. It seemed as if the poets who had remained in Spain wished it could be merely that, even as the war’s ghosts had pursued them their entire trip.

In early March 1950, the Magllanes docked in cold, foggy Galicia. The economic rewards for the poets’ three-month odyssey were meager. To supplement his payment for participating in the trip, Panero brought back contraband to sell on the estraperlo, the Spanish black market: transistor radios, scarves, tights. His spiritual rewards, however, were greater, he claimed. “How glad I am to have done that trip, precisely that one and not another,” he later wrote. “By way of pain, everything so difficult, so Spanishly difficult, so face to face with the truth!” Yet this “truth” would be offered as an explanation for how the experience swung him further to the right on returning to Spain, leading him a few years later to write a book of fiery fascist poetry that was a hate letter of sorts to his former friend, the communist Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. This reactionary book would end up marring Panero’s reputation in the coming decade as Spain’s intelligentsia began straying from Franco, including Luis Rosales.

For the poet from Granada who had provoked so much outrage in Latin America, Lorca’s death would hang over him for the rest of his life, and hang over his son’s life, too. “What happened to Lorca continues to be a nightmare,” Rosales’s son said in 2016, despondent over how Lorca’s assassination eclipsed everything else his father wrote and did, much the way it had done to the travels—and travails—of the “poetic embassy” over half a century earlier. In the latter half of his life, Luis Rosales toiled away on a projected four-book poetic opus that aimed to be the culmination of a life dedicated to verse. He never finished the fourth book of the cycle, New York Despues de Muerto (New York After Death), a journey through the city of geometry and anguish that Rosales imagined taking with his dead friend Federico. This last book was inspired by his 1950 visit to New York and the feelings it had left in him. Whether the “poetic embassy” to the Americas had been a success or not no longer mattered, if it ever had. It had revealed the persistence of the dead, who could not be brought back even through that powerful human creation that has always served as a hedge against eternity—the written word.

“People who don’t know pain are like churches that haven’t been blessed,” Rosales wrote in a book he published shortly before leaving for Latin America. If that was truly what he believed, then he was blessed, abundantly, by the curse of the death of Federico García Lorca.