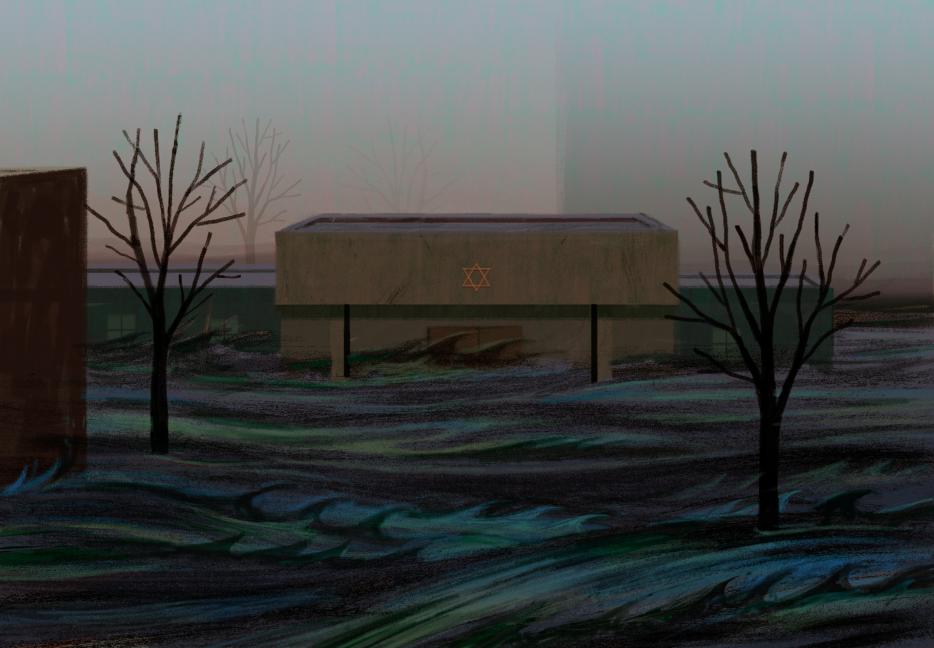

I stand with my family in front of a mass grave of siddurim on Christmas Day. Hurricane Katrina destroyed the 3,000 prayer books belonging to Beth Israel synagogue, and, as per tradition, they’re buried in a Jewish cemetery, next to the headstones of former congregants who looked to G-d in their pages. My father read from those same siddurim after he converted in the summer of 2000.

He’s a neuroscience professor, a man who prefers the Aristotelian logic of Maimonides to the mystical ephemera of Hasidic sages. After a few years’ consideration, Ian Arthur Paul, possessor of arguably the most Scots-Irish name ever strung together, wanted to become a Reform Jew. Despite the denomination’s leniency, he insisted we drive down from my hometown of Clinton, Mississippi, to New Orleans so he could properly bathe in an Orthodox temple’s mikvah. The ritual waters washed off any W.A.S.P. impurities—predilections for bacon no doubt replaced by a sudden, robust interest in gefilte fish and hot pastrami—and Ian emerged a full-fledged Member of the Tribe. He joined my mother, a woman raised in the faith, to impart on their two sons the same story inherently laden with struggle and questions. Entire nations tried to burn us away over the millennia, and now, staring at the memorial marker, it seems like nature had it in for us, too. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina drowned Beth Israel, the mikvah pool mixing with the sewer shit and tidal debris as it flooded the sanctuary with ten feet of water. The temple serving New Orleans’s Orthodox Jews for almost ninety years was completely destroyed.

*

There’s something about a lifetime in the South that can make a post-Shoah Jew feel both a freak and a fraud. As a kid in Clinton, Mississippi, I couldn’t explain theological differences to my third-grade classmates—I didn’t really know myself—so whenever they asked what being a Jew meant, I told them Judaism was “like Christianity, but without Jesus.” For the most part, they’d nod understandingly, a monolithic crucifix central and comprehensible in their lives. Once, a kid cocked his head to the side like a perplexed terrier. He’d never heard of Jews before.

In high school, I learned to use this to my social advantage. Self-deprecation made me approachable, friendly, the sidekick to any clique, so I condoned my lampooning to help generate a social life. My Judaism was an unsightly, suspicious creature I’d graciously dehorned for others to play with, ogle, poke and prod without fear of repercussion.

It never became outright anti-Semitism—thanks in no small part to my self-hate shtick—but Judaism was always getting in the way of things. I was the ninth-grade class president, but when I asked my principal why missing school for Rosh Hashanah counted as one of my six sick days, the spineless motherfucker told me the administration couldn’t be sure I would use the absence for religious purposes. I played tough in a shitty punk band, but you can only be so dangerous when drugs make you anxious and hot mics conduct electricity through your braces. I finally had sex before leaving for college, a feat I thought would be impossible for a Clintonian kike, but that relationship ended shortly after word got out to her Southern Baptist parents. I fell in love with another woman, and when we kissed I could taste the life G-d breathed into her at birth, but I still proceeded to ruin it within a year by fooling around with the first new beautiful woman who showed me the briefest flicker of interest.

Now, eight years later, eleven since Katrina, I’ve almost made peace with my choices— with the relationships that broke more than they mended; with the fact that, had I not taken this or that particular emotional misstep, I might not now incessantly seek a faith in something beyond and better than me. I’ve almost made peace with all this, as I also need to make peace with the possibility of Jewish life as a whole being a tragicomedy.

The entirety of Judaism now barely comprises about 0.2 percent of the world’s population. Of that, 40 percent live in America, 3.5 percent of which live in the South, meaning that only nine percent of American Jews call this region home. An estimated .028 percent of all world Jewry. About 392,000 souls, hardly two generations removed from the industrially efficient genocide that nearly ended us, tethered to a bastardized Israel forged in response to that same surgically precise, state-sponsored slaughter. I’m labeled the historically pernicious “Self-Hating Jew” for critiquing Promised Land policy. I’m decried as a zealot for anything less. If I can’t even find my place within the supposed homeland, then what chance do I have feeling truly at home here? I came to New Orleans to explore my faith and my past, both personal and historic; to come to terms with what, if anything, there is to being a Jew in the South. But by the time I might hope to unpack it all, will there be anything to say?

After locking up the building, Jackie gives me a small tour of their back patio. Wooden picnic tables shine brightly from their lacquered finish in front of two party-sized grills. A large urn fountain sputters water over its brim in the middle of a manicured flower and herb garden. Like the rest of this Beth Israel, it all feels too new, giving off a sense of tense expectancy, as if waiting for a history to imprint upon it. Births to be celebrated, lives to be lived, deaths to be mourned. Storms to be weathered.

Jackie points to a large shrub in a corner.

“You cook?”

“What?” I ask.

“Rosemary, you want some for cooking?”

“Oh, sure,” I say.

Jackie snaps off a bushel’s worth of herbs for me.

“I don’t know if I need this much,” I say, laughing.

“Oh, please. Take it. I brought this thing here after it got too big for my house. Now it won’t stop growing.”

We say our goodbyes. I offer to walk Jackie back to her car, but she says she’s going to stick around for a little while longer. She’s got new flowers to plant, and there are weeds that need pulling.

*

I visit Beth Israel’s cemetery alone that weekend, and, per Jackie’s directions, find the second grave, this one home to the decayed Torahs. It’s been six months since I last visited here with my father. It’s much hotter now. A man across the street is hunched over an open car hood, working on its engine as the stereo speakers blast New Orleans bounce music. Five minutes outside, and I’m schvitzing through my shirt. Meyer Lachoff’s headstone neighbors the Torahs he cared for—he and the scrolls died almost the same day.

There’s the story of a rabbi from Prague, fearful of the European pogroms, who builds a protector out of clay, a golem, to save his people from persecution. To bring it to life, he inscribes the Hebrew word for truth, emet, on its forehead. There are variations of the tale, but it usually ends with the golem becoming as serious a threat to the persecuted as to the persecutors. An unbridled, thoughtless, destructive behemoth, the embodiment of Judaic prideful passion run wild. Realizing this, the rabbi lures the golem back to the town’s synagogue. He rubs away the letter aleph from the beginning of emet. Now, it simply reads met, death, and the golem falls to pieces, crying out for his abba, his father.

Ian Arthur Paul, eager to impart Jewish culture on his firstborn, first told me this story before bed when I was ten years old. It kept me up all night. The pain of the golem, a creature who didn’t ask for its heritage, who only wanted safety and justice for its people, remains with me. Sometimes, when I’m alone and can’t sleep, I think about the rabbi’s golem, and I wonder what would happen if it were constructed from Southern soil. Would the Yazoo clay let it live a malleable life, to mold to its surroundings with ease? Could it give up its incessant need for self-righteous, violent opposition? Could it love this world thrust on it, or would it crumble away in the floodwaters, washing downstream, crying out for its Creator to reconsider?

I say kaddish, and go home.