Anna Kopec always knew she was different. Until she turned eight, she thought it was because she was adopted.

"Even just sitting at the dining table. I looked around, and I didn't look like them. I didn't look like my family," she says.

That's not entirely true. There is a resemblance between Anna today, at age twenty-seven, and her mother Maria; she has the same aquiline nose, dimpled chin, and dark brown hair. But her dark complexion, skin the colour of caramel and eyes like pools of amber, stand out in the framed photos that line the walls and mantel pieces of her Polish family's home.

Back in the '90s, when she was growing up in Edmonton, there were whispers in her tightly-knit Polish community. Heads turned when Anna attended Sunday mass; she could feel the eyes boring into her back as she sat attentively during the service. But the whispers and close attention didn't get to her until, at around age five or six, she started Polish dance classes. Even though Anna was dressed in the same colourful outfits as the other kids, a red skirt and white shirt worn with a black vest and white lace apron, decorated with multicoloured floral embroidery, she stood out. The students called her chocolate—which didn't bother her at first, it echoed a nickname from her grandfather. But, for the two years that Anna attended the classes, she would often end up sitting by herself in a corner, reading a book. The Polish woman running the program occasionally got her own son to dance with Anna. When Maria found out that her daughter was being ostracized, she was furious. She yelled at the dance teacher and said Anna wouldn't be coming back. "That's when I realized something was going on."

Every now and again, Anna would ask her mother why she was brown, why she was darker than everyone else in the family. Her mother would say she would tell her soon or change the subject.

When Anna's sister Barbara was in grade four or five, she asked their mother the same question. Why did Anna look different? "She had told my sister that because I was born premature, I was put in an incubator," says Anna, shaking her head. Barbara repeated this explanation to her friends at school, and Barbara's friends went back home and told their mothers, who told them that's not how it works. Kids can be cruel, and Barbara became the laughingstock in the schoolyard.

One day, after a shopping trip to buy Anna a figure-skating dress for an upcoming performance, her mother took her to McDonald's. Anna was excited to get a Happy Meal because her mother didn't usually buy fast food.

"I can still remember the skating outfit was hanging off the back of a chair," says Anna. "I was eating Chicken McNuggets."

That's when Maria told her that Woody, the man Anna had grown up calling Tata, was not her biological father. Her real father came from Sri Lanka. His name was Duke.

When they got home, Maria gave Anna a picture of Duke. Anna felt a sense of relief. Her mother was still her mother, and she didn't feel any different towards her Tata. Her siblings Barbara and Lukasz were still her sister and brother.

A few days after her mother told her about Duke, Anna wrote the following entry in her journal, in alternating purple and blue glitter gel pens:

![Okay so the big secret is that when my brother and sister were born there [sic], real father was Woody. Then Woody left somewhere and then my mommy had me with my real father Duke. Duke was brown that’s why I’m brown. When Woody came back my mom had to choose either to stay in Germany with Duke, Me [sic] and my brother and sister or to go to Canada with Woody and take all of us. So my mom picked to go to Canada with Woody. Then one day my mom got a phone call that Duke had died. So my mom waited until I was older and the [sic] one day she took me to McDonald’s when I was eight and told me. Now I have pictures of Duke and I make cards for him and put it beside his picture. Well anyway Bye! [sic]](https://hazlitt.net/sites/default/files/diaryspots_1_1.jpg)

It wasn't until years later, when Anna was entering her teenage years, that she started to ask probing questions. Who was Duke? Where in Sri Lanka did he come from? Was she like him? Maria didn't seem to understand why Anna needed to find out more about her Sri Lankan side when she already had a family that loved her. The rest of Anna's family was sympathetic to her search but couldn't help.

When she was sixteen, during an annual trip to see her extended family living in Germany and Poland, Anna decided to try to find out more information about her biological father herself. It was a spur of the moment decision, which she hadn't discussed with her family in Canada. Her parents had divorced, and Anna was living with Maria. While Maria didn't seem to understand Anna's quest, Woody encouraged her to find her own answers. She enlisted one of her German cousins in her search, and managed to find a date of birth and date of death for a man named Duke Santhira. Woody's mother showed her a few more photos, but that was all Anna could find out.

A few years later, in October 2013, a chance conversation with one of her university professors put her in touch with Sri Lankan Canadian academic Amarnath Amarasingam. He was travelling to Sri Lanka in January. He asked Anna if she wanted to come along.

"I didn't even have to think about it," says Anna. Immediately she wrote back: Yes.

Ten days before Christmas 2013, Anna and her now-husband Gurvinder Gill travelled to Sri Lanka. This is all they had to go on: A name, likely assumed. Duke Santhira. Duke's birthday and the date of his death. A few pictures.

Poland: When Woody Met Maria

Wlodzimierz Kopec first saw Maria Czweryn on a bus in Warsaw, Poland. It was the early 1980s. She was eighteen, and he was twenty-three. At the time, Poland was still under the rule of a communist government that played by the Russian rulebook. Wlodzimierz saw Maria on the bus on his way to work at Mazowieckie Centrum Rehabilitacji Stocer, a hospital in Konstancin-Jeziorna. It was a long bus ride from his home in Warsaw. He was working as a nurse's assistant there. Maria's bus stop, on her way to a horticulture school, was a couple of stops before his. "Caught by her beauty," he says, he asked if he could walk her to school just as she was about to step off the bus.

Wlodzimierz, who started going by Woody after his move to Canada, sits in the dining room of his Edmonton home. He's wearing a white shirt and jeans, his blue eyes piercing through a pair of Hugo Boss glasses. He speaks in short, Polish-accented bursts. When he stops speaking to collect his thoughts or search for the right word in English, he stares out into the distance, looking through the glass sliding doors that open into a small backyard blanketed in snow.

As it happened, Maria lived very close to Woody; he passed by her apartment every day. They dated for a year, and then Maria wanted to get married.

Woody had lived an idyllic childhood. He came from a middle-class family. His father had served in the army, and when he was a child, both his parents worked at Fabryka Samochodów Osobowych, a famous automobile manufacturer. The family lived in a hotel for factory workers, sharing one room separated by curtains to create a bedroom, kitchen and living room. Just before he started school, the family moved into a new apartment in Warsaw.

After finishing school, he went straight to work at a newly opened factory for retreading old tires. He got the job after meeting the director of the factory through his father. After a stint working at the hospital instead of military service, an assignment that was the result of his poor vision, he returned to the tire retreading factory.

"It was a new plant in Poland, with Italian equipment. [The boss said] there might be a chance to go to Italy for a course," says Woody. "Getting a passport was impossible. Only party people had them. Regular people stayed in Poland and worked where they were told to."

Maria's father had been a middle-ranking officer in the Polish army. When Maria was seven, he died of carbon-monoxide poisoning. Maria's mother moved with her four daughters to Warsaw in 1972, where the army gave them an apartment.

"We weren't poor-poor, but we didn't have much money," says Maria. She's moving around her kitchen in Edmonton, putting together a meal of pork tenderloin and vegetables, while constantly apologizing for not being able to make a proper dinner.

Maria lives a short drive away from Woody. Compared to Woody's minimalist home, with neutral beige walls punctuated with family photos, Maria's home is warm and cozy, with a large Christmas tree standing tall in the living room. Dressed in a chic blouse and pants, her eyes sparkling with flecks of glittery gold eyeshadow, Maria is charming to a fault, constantly offering a glass of wine or a cup of tea.

"My mother had major depression, and she was bringing up four daughters. I was practically raised by myself … My sister Anna had left for Germany when I was in high school. I didn't have the greatest relationship with my mother."

Outside their family home, an apartment in an historic part of Warsaw that was rebuilt piece-by-piece after being obliterated in WWII, tanks were rolling down the streets following the announcement of martial law in 1981. "You had to be home by 8 p.m. There was rationing of meat and sugar."

While she aspired to become a psychologist, Maria took a practical look at her options, and told Woody she wanted to get married. And so they did, in 1983.

Life was not easy after marriage. They had to contend with the challenges of living in a communist society. "Corruption was enormous," says Woody. "It was the main reason to leave."

Barbara was born in 1984, and Lukasz in 1986. The family was living in a simple cottage in a small district in Piaseczno County. Woody was doing shift work at the tire factory, also making some money under the table, and he and Maria were fighting. "Main reason for Maria was that I drink too much." He did drink a lot, he admits. It was easy to buy vodka, and much harder to refuse his friends who wanted to drink after work. Besides, he wanted to stay away from Maria's screaming.

Maria remembers being stuck at home with two little kids and washing and boiling an endless load of diapers. "I got twenty diapers, you know how? Each gynecologist gave you ten diapers for a baby. Cloth diapers, not the modern ones like now. So, I went to two different gynecologists," she says. "I was twenty-two years old, with no running water, no heat … We didn't have milk for the kids. Only vodka for the men to drink and get angry."

Maria's three sisters were already in Germany. Woody went to Germany in 1988 and started to work in the black market doing industrial renovations-drywall, taping, cleaning work spaces and delivering materials. "What I made in one hour in Germany was worth more than a month's work in Poland," says Woody. His idea had been to stay in Germany for a few months at a time to work in the black market and spend the rest of the time in Poland.

Life was tough while Woody was in Germany, says Maria.

"I used to wake at 5 a.m. and take a stroller that was made in Czechoslovakia and walk five, six kilometres to the nearest market. It was a big used stroller, so no bus would take me. I would get eggs and the best meat," she says. "But sometimes there was no food. I had to go around and barter for milk. So, one day I put on my nylons and lipstick, and one of my sister's friends came and took me to the German embassy. There were people sleeping on the streets for three months to get a visa. But somehow, when I went, the person opened the gate and I walked out with a visa. We went with my sister's friend in a car to Germany. Woody was not impressed when I showed up there."

Maria arrived with Barbara and Lukasz in Germany in September 1989. "Maria wanted to apply for asylum in Germany. I thought it was a stupid idea, but all the sisters persuaded me," Woody says.

Germany: When Maria Met Duke

In 1989, communism fell in Poland, and getting asylum in Germany was tough. Maria, Woody, and the children were facing deportation. Maria had heard Canada was taking in refugees from Germany and had written 180 letters to Canadian and American sponsors. A sponsor in Edmonton agreed to take them in, extending their temporary refugee status in Germany. While they waited for the papers to get processed, the family was sent to live in a small town called Rüthen, where many other refugees were also sent to live. They were given accommodation in the upper portion of a two-storey home in a lower-income housing complex, a place that the family came to call the refugee hotel.

Although they were given an allowance to meet their living expenses, Woody continued to work under the table. Every week, he travelled to Cologne, a two-hour trip one way taking a bus and train, to save up money for the airplane tickets they would need to travel to Canada.

"That's when Maria met Duke, Anna's father," says Woody. Duke worked in a pizzeria in Dortmund. When he wasn't working, he'd visit a friend living next door to Maria.

In Rüthen, Maria walked everywhere. To the market, to take the kids to preschool. "With my luck, it was always raining. One day, this red car stops, this red Ford, as I'm walking. It's Duke. And he says, 'Don't be afraid.' I got in and he took us to the daycare. I left the kids and went grocery shopping with him. Then I invited him over for tea."

Woody knew Maria was lonely in Rüthen. "She was complaining I was out of town, staying with friends. I was drinking," says Woody. He told her, "I know it's hard for you. But listen, we decided we are waiting to go to Canada. I have to suffer, you have to suffer."

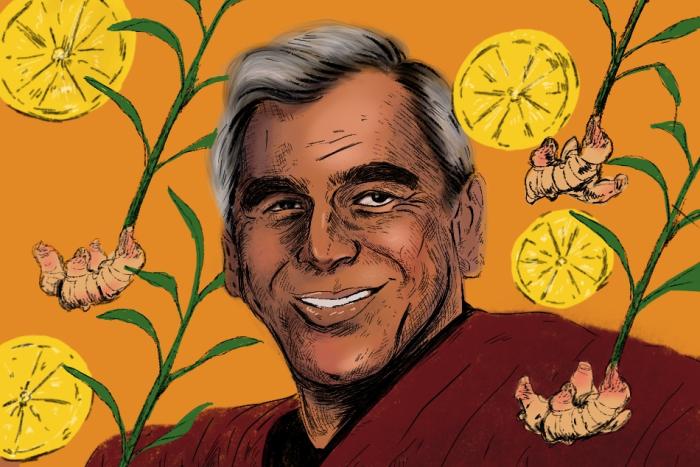

Meanwhile, Maria says, Duke took her and the children to McDonald's and the zoo. They started becoming very close. He told her some stories about life back in Sri Lanka, how his father had the first car in Jaffna. But he didn't talk about why he had left or the civil war that had started in 1983. Instead, she found out through his friends that he had been tortured. "He had scars on his body," she says. "He had the biggest smile. He didn't laugh loudly, but his smile was beautiful. He sang in Tamil, he was always whistling. And he got these beautiful letters from his mother, the [writing] was like artwork."

They fell in love. "He was a really gentle man, a gentle soul. And I had lots of suffering inside me. We had our little talks, but people who go through things, we don't talk about that stuff. It's not what you want to remember."

When Maria found out she was pregnant with Duke's baby, she was shocked. Her first instinct was to go for an abortion. She even visited a doctor with her sister Elzbieta but couldn't go through with it in the end. She told Woody about the pregnancy.

"I was devastated," says Woody. A deeply Catholic man, he decided this was God's will. He told Maria, it's "something not for you or me to decide. I know I wasn't maybe very good to you. Maybe I have made my mistakes. Maybe that's the price I have to pay for it. And I forgive you everything. Let's start life together. It's new life in front of us, new country."

Coming to Canada

Anna was born on December 29, 1991. The Kopec family left for Edmonton in May 1992. "It snowed the day we landed in Edmonton. It was a huge snowstorm, there was a big dump of snow," says Anna. "My mother used to joke that she should have known to go back right then."

Like many new immigrants to Canada, they struggled at first. They started out living in the same house as their sponsor, Piotr, who had a younger brother, Jacek. Woody started helping Piotr paint and do renovations, eventually found a job in landscaping and gradually started picking up piecemeal work in construction. Maria worked three jobs, sending the kids to visit their grandparents, aunts, and cousins in Europe regularly. She learned English by reading Danielle Steel novels, and cleaned townhouses to help with the family expenses while Anna napped in a stroller. Eventually, she became a nurse.

For four years, Woody and Maria stuck it out despite their differences. They were immigrants in a new country, and it made more sense to live together. Moreover, given his faith, Woody did not want to get divorced. But in 1996, they decided to go their separate ways. They got a divorce in December 1998.

The transition to Canada wasn't without bumps for Barbara, Anna's older sister, either. She has fond memories of growing up in Poland.

Barbara looks straight ahead as she talks, as if watching a movie about her own life, trying to rewind and pause. Sitting in the expansive kitchen of her large suburban Edmonton home, light filtering in the large windows, Barbara pushes her bottle-blonde hair behind her ears and pulls on the sleeves of her sweater. She's lithe, petite, a no-nonsense version of Renée Zellweger.

In the beginning, life in Canada was an adventure—a new school with new friends, new experiences like making snowmen outside the house, Jacek dressing up as Santa Claus for Christmas. But Barbara started to notice the strained relationship between her parents. On a road trip one summer, Barbara remembers telling her brother Lukasz that she thought Jacek was in love with their mother. Barbara struggled with the tense atmosphere at home, disappearing into the basement to hide her tears.

"When I visited my dad, I would take cutlery or cans of food because he left with nothing," she says, tears rolling down her cheeks. "That was my Grade 4."

Meanwhile, Barbara was also dealing with the constant chatter in Edmonton's tightly knit Polish community about Anna not being her real sister. "I hated going to church, hated going to religious class because it was all Polish. I hated going to the Polish Saturday School because a teacher pulled me aside one time and asked me, 'Why is your sister brown?'"

Her animosity towards the Polish community and the Polish church deepened further. When she was hanging out with her non-Polish friends, there were no questions. Her resentment was so deep that she didn't even want to go for her Communion, dressed up in a hand-me-down outfit, her hair in a formal 'do. The classes leading up to the religious ceremony had been unpleasant, with kids whispering loud enough for her to hear them question whether Anna was adopted, and whether Woody was her real father.

Barbara remembers being about thirteen when her mother Maria showed her a picture of Duke. All the resentment she had felt about dealing with the rumours at school and in the Polish community turned towards Maria. She says she told her mother that Anna needed to know the truth.

Barbara had pulled away from Anna. It was partly the age difference between them, and partly the bullying she faced because of Anna's parentage. So, when Maria decided to tell Anna, Barbara wanted no part in that conversation.

"I feel like I ignored her until she was about fifteen, sixteen," says Barbara, overcome with emotion. She walks away for a few minutes, composes herself before taking her seat again. It wasn't until Anna was a young adult herself, and Barbara was getting engaged, that they truly bonded. Even so, a few years later, when Anna started to look for her father in earnest, Barbara couldn't help her. "I could not remember anything."

Anna's Story

The dreams started when Anna was about twelve years old.

At first, they were simple. She saw herself going for a walk with Duke, who was always in a green shirt, the same shirt he was wearing in the photograph that Maria had given her when she was eight years old. This was around the same time that Anna had started to ask more questions about why Duke hadn't come looking for her. Maria told her that Duke had been sick with some sort of blood disease, and he'd died because he'd stopped taking his medications, collapsing in the pizzeria where he worked.

By the time she was fourteen, the dreams had turned into nightmares. Anna dreamt she was holding a bottle of pills, Duke's medicine; sometimes he was sitting by her bed, sometimes on the floor and sometimes kneeling over the toilet, asking her for them. But for some reason, Anna couldn't give him the pills.

"I would wake up sweating and crying. I was terrified," says Anna.

Barbara had been right about Jacek and Maria—the two married when Anna was around twelve.

"He'd been in our lives since day one in Canada. He was always there," says Anna. Jacek became like a father-figure. When Anna started having her nightmares, she first confided in Jacek. "He said, you need to talk to your mom."

Despite Anna pestering her for details, Maria didn't tell her much about Duke beyond the fact that he was born in Jaffna, Sri Lanka. When she asked Maria why Duke didn't visit her before he died, Maria explained that Duke had kept in touch for a while, but he couldn't get a visa to Canada. She remembers her mom telling her that he asked for Anna to visit, but by the time their family got their Canadian citizenship, allowing them to travel, Duke was dead.

But the stories also kept changing. Anna remembers that Maria told her that Duke and Maria had stopped talking. In one version, she told Anna that Duke had managed to get as far as the United States border, but that he was sent back.

"The story was never really the same," says Anna. "Sometimes she would give me little stories. That he loved spicy food. Or that the civil war had been really hard on him. Or one day we were sitting on the couch painting our nails, she had a nail file in her hand, and she said, 'I don't know what to say. He laughed a lot.' I randomly started thinking that maybe he's alive, she doesn't want me to see him. The rebellious teenager in me started thinking, maybe I will find him."

When she was fifteen, Anna wrote to Dr. Phil and Oprah, hoping one of them would help her with her quest. She didn't hear back from anyone and decided to take matters into her own hands. Anna had been travelling solo to Germany and Poland to visit her extended family since she was nine. By the time she was sixteen, her relationship with her mother had started to deteriorate. Anna decided to go back to Europe with a mission to find out more information about Duke from her other family members. She didn't tell anyone about her plans until she landed in Germany, and contacted an older cousin, Michael, her godfather. Michael lived near Dortmund, the city where Duke had lived.

After Michael agreed to help her, Anna told her aunts about her plan. They didn't have much information about Duke. Her grandparents didn't have much to add either, even though Anna knew about Woody's father's animosity towards Maria and her infidelity. But her grandmother was understanding about Maria's situation. Her own marriage to Anna's grandfather had been more for convenience than love. She showed Anna photos she had of Duke and shared her memories with Anna. "She told me, 'I could tell they were in love. I could tell something was there, that it wasn't just [a fling] to her."

Anna visited a hospital where she had stayed as a baby and the housing project where Duke and her mother met. She and Michael went to Dortmund's registry offices, to look for Duke's birth and death records. At first, the officials weren't prepared to give Anna the information, because she wasn't legally on his records. Anna was crying out of frustration and said her piece to a woman in the death office. Anna isn't sure what she said, or how she said it, but something struck a chord with the woman. After they left, the official started looking through stacks of paper files. When, at first, she couldn't find a record, Anna's hopes lifted for a moment; maybe there was a chance that Duke was alive. But Anna got a call later that night; the woman had stayed back at the office, searching for hours. The official gave her a date of death, April 24, 1995, and a cause: a brain aneurysm. Duke had no grave. His ashes had been scattered.

Anna was distraught, and called Maria in Edmonton, hysterical. But Maria didn't understand. "Well, you knew he was dead," she said. When Anna returned from Germany to Edmonton, she went to a cemetery with Jacek and Woody to set up a little plaque for Duke. Her relationship with Maria continued to break down.

Going to Sri Lanka

When Anna was in her third year at the University of Alberta, one of her professors introduced her to Amarnath Amarasingam, a Sri Lankan Canadian academic who has studied the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora and its politics. Amarnath was working on a project on post-war reconstruction in Sri Lanka. The professor suggested that Amarnath may be of some help to Anna in her search to know more about Duke. Anna sent Amarnath an email on October 27, 2013. It was a Sunday afternoon.

"My story is a little complicated, but I will do my best to tell it in a swift and quick manner as to not take up too much of your time," Anna wrote. She provided a brief summary of her story, including her father's name, which she acknowledged might be an alias: Duke Santhira Sathusigaman Pillai.

When Amarnath received the email, the first thing that struck him was how little information there was. "All she really had was this name Duke, and the fact that he came from Jaffna. That's like me saying I need to find a guy called Duke in Toronto. Actually, scratch that. It was like, I want to find a guy called Duke in Ontario." Anna had attached two pictures of her father, as well as a picture of herself and a tiger pendant that Duke had given Maria.

It was like a puzzle. The name wasn't a common Sri Lankan Tamil name. Then there was the tiger pendant, suggesting an affiliation with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a militant organization that sought a separate Tamil state in Sri Lanka. It added complications to asking questions about Duke and his family. Nevertheless, Amarnath could understand Anna's desperate attempt to look for her father.

Amarnath asked family and activist connections back in Sri Lanka if they could help by tapping into their community network. However, there wasn't enough information to go on. A few weeks passed, and it became apparent to Amarnath that any meaningful search would need to happen on the ground in Sri Lanka.

"Especially with that pendant. Usually people don't want to have anything to do with any Tiger-related stuff … We knew nothing about his connection. It could have been nothing. Or he could have been some high-level guy. We didn't know why he fled to Germany," says Amarnath. "People are usually more willing to talk face to face."

He had been planning a trip to Sri Lanka to conduct field research and interviews with former LTTE fighters who had undergone rehabilitation. A friend, Kumaran Nadesan, a Sri Lankan Tamil Canadian who works as a senior business consultant with the government of Ontario, was going to join him. Kumaran was looking to do some ground work in establishing a not-for-profit that provides assistance in sustainable development in the north and east of Sri Lanka. On October 31, 2013, Amarnath sent his flight plans to Anna.

Anna's email and subsequent phone conversations with Amarnath had shown her how little she actually knew about Duke or her Sri Lankan heritage. While Anna had read up briefly on the civil war that affected the country for twenty-six years, she wasn't aware of its complexities. Every time she corresponded with Amarnath, he was full of questions: which town in Jaffna was Duke from? Are you sure you've spelled his name right? However, the minute Anna read Amarnath's email about his upcoming trip to Sri Lanka in January 2014, she knew she was going to tag along. The only person who knew about her plan at that point was her now-husband, Gurvinder.

The flights to Sri Lanka during peak season were expensive. At the time, Anna had no money and Gurvinder was working, so he fronted the $3,000 for the airfare for the both of them. "We booked the tickets without talking to my family," says Anna. "I was totally not thinking rationally."

Anna finally told her family a few weeks before she and Gurvinder were supposed to leave. Her sister was skeptical but supportive, Woody was excited, and Maria was shocked.

As the date for their departure crept closer, Anna got more and more excited herself, but it wasn't until shortly before the flight to Sri Lanka that the anticipation really hit her.

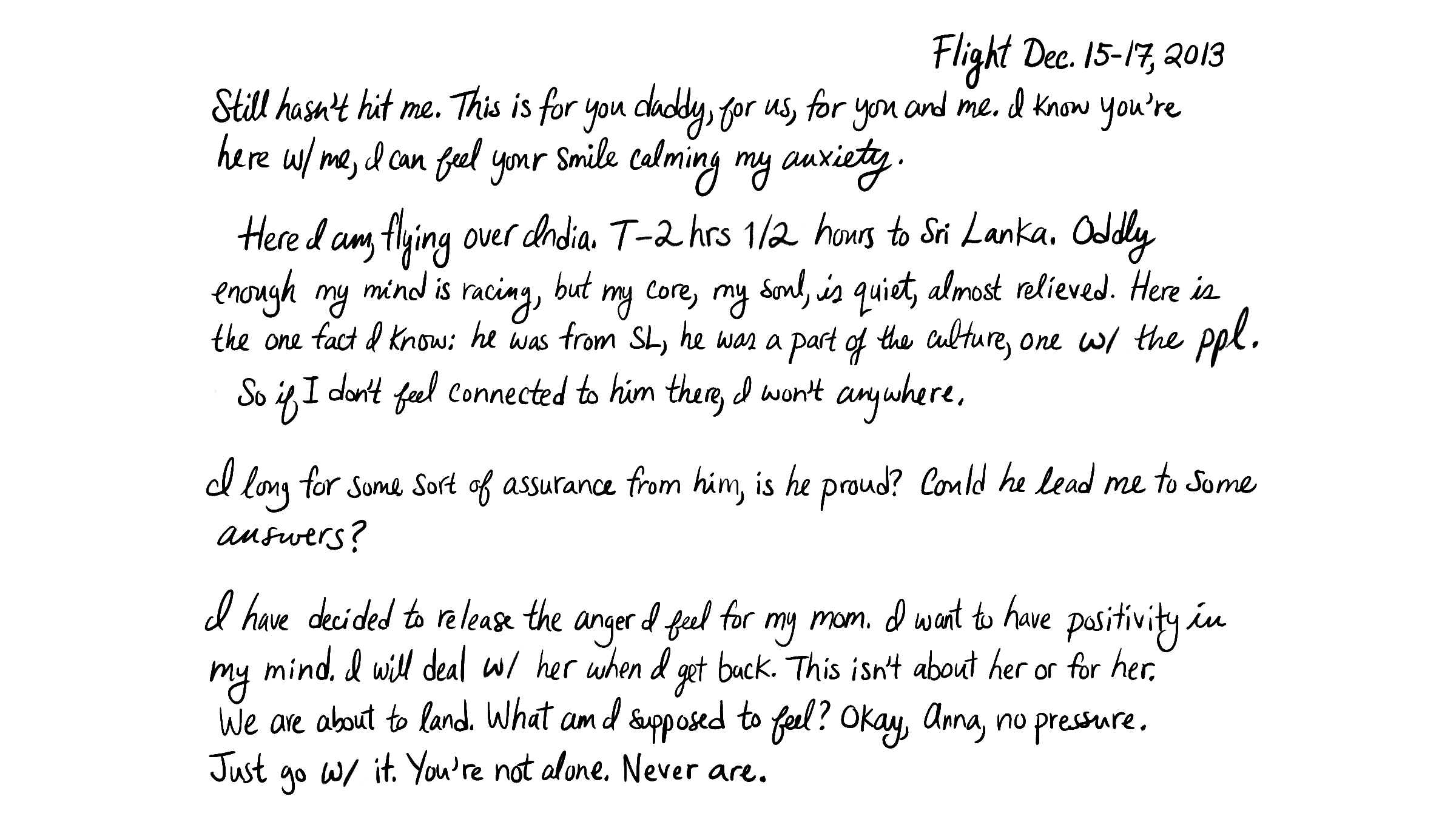

An avid journaler, Anna kept a record of her visit in a black-and-gold embossed notebook. It's titled Sri Lanka: Dec. 15, 2013-Jan. 11, 2014. A Journey to find myself.

The first entry reads:

As they stepped out of the airport into the humidity of Colombo, Sri Lanka's capital, and started the drive towards their hotel in Mount Lavinia, Anna was struck by the lush landscape, where the palm trees grew in clusters. But as the highway gave way to an urban environment, she started to truly get a sense of the chaos of a large Sri Lankan city. The buildings looked older, dotted with large, brightly coloured billboards, the traffic was a mess, with a car honk signaling, "Oh hey, I'm gonna do this, okay?"

Their hotel room had a view of the waves of the Indian Ocean slamming into the shore. After a quick shower, Anna went for a walk on the beach with Gurvinder. They came across a snake charmer with a cobra and a monkey, crude boats and shanties. Anna started thinking about the poverty she was witnessing in the midst of the beautiful surroundings. "I think back and wonder what he lived in, what his family, if alive, lives in now," she wrote. The entry for the day ends with: "I feel like it hasn't hit me yet, except in some particular moments. But I am ready to embrace me, my other half. Daddy I feel you, please be my tour guide."

Discovering Sri Lanka

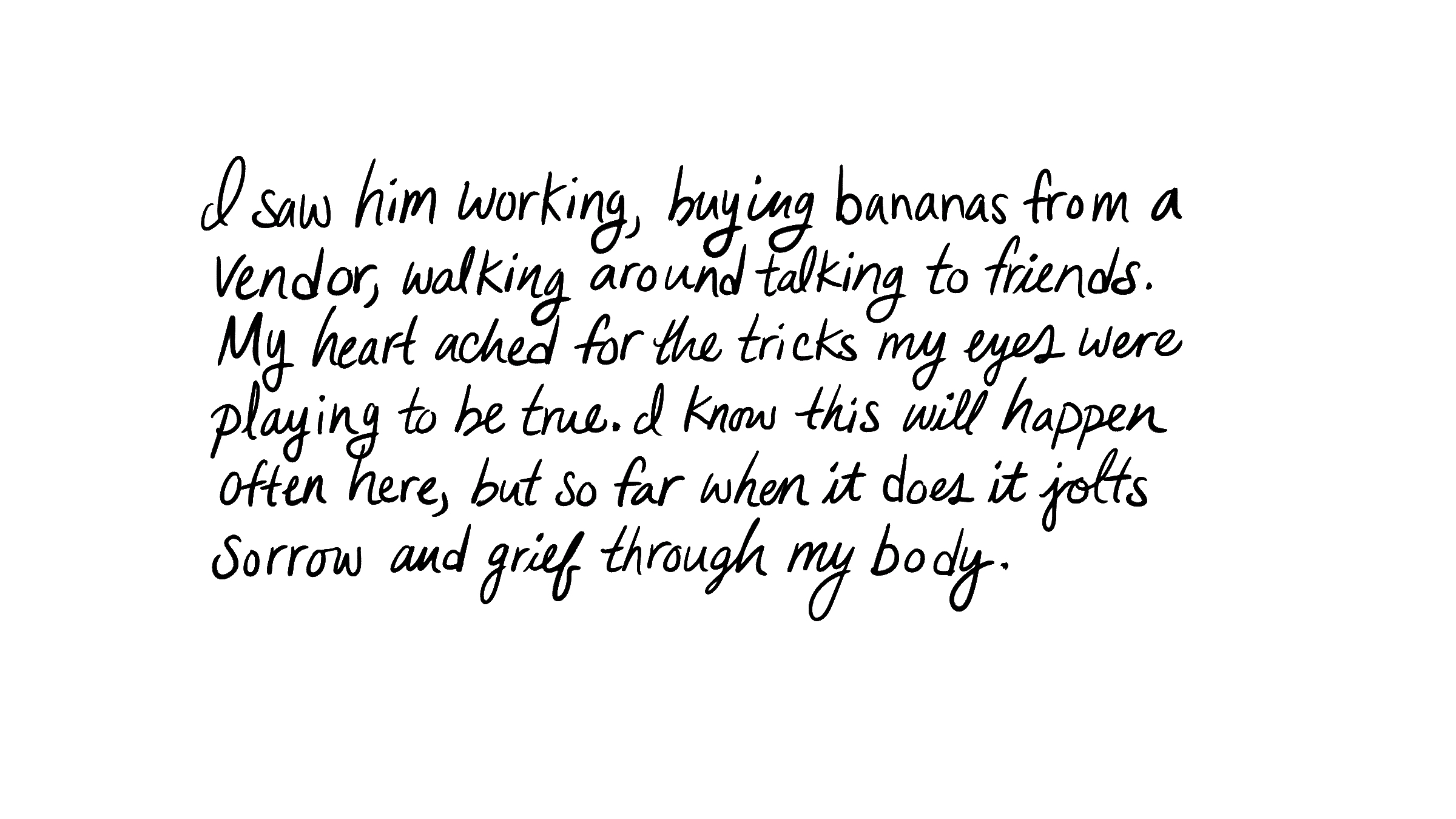

Navigating this new place was a daunting task, and one that Anna wouldn't have had to figure out if Duke had been there to guide her. Every time she noticed the local men, she thought she was seeing Duke.

It would be almost two weeks until Amarnath and Kumaran joined them. Anna and Gurvinder spent that time taking in some of the spectacular sightseeing spots in Sri Lanka. They explored Anuradhapura, one of the ancient capitals, the rock fortress Sigiriya, the Dambulla cave temple and the city of Kandy, which houses a sacred Buddhist relic in one of its temples. "One of our tour guides, he was Tamil. I asked him how it was for the Tamil people in Sri Lanka, and I got a kind of a crash course," Anna says. "I liked it that way, physically being there … But then there were times when I disconnected from Sri Lanka."

While the landscape was breathtaking, their mornings started with delicious local food and fruits, and evenings ended with one spectacular sunset after another, the devastation of the decades long conflict between the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE fighters was apparent behind the facade of the tourist attractions.

Anna had long had an interest in political science. She had studied various conflicts in Africa and travelled to Kenya after high school after saving up money from working a few retail jobs. On the flight to Sri Lanka, she skimmed through Amarnath's PhD dissertation to augment her Google searches on Sri Lanka's painful past. She was "aware of the Sinhalese-Tamil divide" from an academic perspective but didn't know much about how the country was moving forward in its reconciliation process.

When she first saw large billboards of then-Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa dotting the landscape, he seemed like a "wannabe Putin." It wasn't until Anna and Gurvinder accompanied Amarnath and Kumaran to the northern parts of the country that had seen the worst of the conflict that she could appreciate the devastation. For the moment, however, it was too much to take in. Instead, Anna concentrated her mind on the task at hand—finding any information about Duke.

A Motley Crew

The vacation part of their trip was over. The day before New Year's Eve, Anna and Gurvinder met Kumaran and his friends at a restaurant in Colombo. Kumaran and Gurvinder instantly hit it off, joking around like old friends. Over crab and fish curry, which Kumaran insisted they eat the traditional way—with their hands, which was a novel experience for Anna—he and his friends heard Anna's story. "It just sounded like such an amazing adventure," says Kumaran. "And I was impressed that Anna had decided to go on this journey."

Over the next couple of days, as they met more of Kumaran's friends, Anna would tell and retell her story. She was taken aback by how touched people seemed, and how everyone wanted to help her in some way. They would try to fish out more information or ask her questions about things she may not have considered in her search.

For people who heard the story, it was kind of a contained problem, says Amarnath. "It's not like we were trying to fix world hunger or something. We just needed to find this person called Duke. Plus, Anna came off as quite charming and innocent. People wanted to do something and help."

For Anna, the help she was getting from relative strangers was completely at odds with her mother's apparent lack of interest. As each day passed, she was feeling more and more aware of how little information she had to go on.

Amarnath arrived in Colombo on New Year's Day. Amarnath, Kumaran, Anna, and Gurvinder walked around the city. While Kumaran and Gurvinder joshed around, and Amarnath maintained his circumspect air, Anna's frustrations continued to build.

The next day, the frustration she'd been dealing with the day before had manifested itself as a throbbing headache. A sense of helplessness and self-pity gave way to anger. She and Gurvinder stayed in the hotel, stepping out only to grab a bite of pizza. Anna finished reading Secret Daughter, a book by Canadian author Shilpi Somaya Gowda, about a young woman who was adopted out of India as a baby by an American woman, and who travels back to India to search for her roots. The not-so-happy ending reminded Anna that her own search may not end the way she hoped it would. It helped her come to terms with her own situation.

The quartet left Colombo for Jaffna, the capital of Sri Lanka's northern province, on January 4. It was a Saturday, and sitting at the airport, Anna was anxious, trying to keep her expectations low. The drive of about 400 kilometres from Colombo was covered in a little over an hour by a small propeller plane.

From the sky, Anna could see green trees and bright red dirt. But the bus ride from the airport to their hotel showed a different landscape, in stark contrast to Colombo. The buildings in Jaffna were older and looked poorer, many houses missing half of their structures. While the protracted civil war affected much of Sri Lanka, it was nowhere more apparent than in the northern region. The LTTE's stronghold, it bore the brunt of a sustained offensive by the Sri Lankan government.

At the time, former Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa was still in power. It had been five years since the brutal end to the civil war, but not much had been done to heal the deep wounds of the long battle and its grizzly finish. Facing heavy criticism from Britain and the United Nations calling for an investigation into human rights violations in order to properly launch efforts at reconciliation, the government continued to deny allegations of war crimes committed by the Sri Lankan army, refusing entry to the UN team tasked with the investigation. Meanwhile, rebuilding homes, returning land, and dealing with displaced people weren't given as much importance as repairing physical infrastructure such as roads and electricity networks. A military presence continued in the north, and many former LTTE rebels as well as civilians spoke about living under a constant sense of surveillance.

Anna was slowly becoming aware of some of these realities.

In Jaffna, the group had been mulling over the idea of taking out a newspaper advertisement, looking for more information on Duke. A journalist working for one of the Tamil papers cautioned the group against publishing Anna's story, suggesting instead that they look at the government birth registry. Working on the assumption that Duke might have been Catholic—because his did not sound like a Hindu Tamil name—the group visited a Catholic priest Amarnath knew, Father Vasanthan.

Father Vasanthan suggested that if Duke was indeed Catholic, there would be a record of his sacraments. However, with records dating back to the 1700s spread out over thirty parishes, they needed to narrow down the search. Time was running out; within a week, Anna was supposed to leave Sri Lanka.

On Sunday morning, Anna attended mass. Father Vasanthan and another priest were running the sermon, about the biblical Magi, or the Three Wise Men, and their journey to find Christ. She wrote that "the priest said how it is a journey we all take to find ourselves. Directly speaking I am on that journey. Finding out more about him means finding out more about myself."

After praying at the church, Anna and Gurvinder walked with Kumaran to a temple. They stood in front of Ganesh, the elephant-headed god said to be the remover of obstacles. Anna closed her eyes, and asked for help.

On Monday, with five days left in their planned stay, the group, along with Father Vasanthan, went to the Jaffna Divisional Secretariat to speak with a civil servant. Nothing. The rickshaw driver they had hired called two of his friends who lived in Germany in the '90s but came up empty. The priest asked one of his friends who also lived in Germany, but it turned out to be another dead end. With every no she heard, Anna's heart sank further.

Based on some Facebook research conducted by Amarnath's reporter friend, the group visited the Catholic church in a nearby village and looked through the baptism records there. They found an entry for a man named Duke, but it wasn't Anna's father. Annoyed, Anna stepped out of the church to call her mother, who was again unable to give her any more answers. Anna lashed out and hung up.

Anna's calls to Maria were frustrating for everyone, says Amarnath. "We felt she had more information that she was not telling us. That became difficult to get beyond. So, I told Anna to stop calling her. I figured either she doesn't know, or she won't tell you," he says.

Gurvinder was cracking jokes and trying to make Anna laugh, but sometimes ended up exasperating her further. They were like an old married couple, says Amarnath. Meanwhile, wanting to get on with networking for his own project, Kumaran would have to leave the group for meetings. And he wondered, even if they manage to locate Duke's family, how they would react to Anna.

As a last resort, the group went with Father Vasanthan to the offices of Uthayan, one of the largest Tamil newspapers in Jaffna. The visit to the newspaper's office once again brought home how brutal the Sri Lankan civil war had been. "There were posters everywhere with pictures of dead journalists and other dead workers who were murdered by the army or the LTTE," wrote Anna. "There were bullet holes, some with casings, still in the wall. It was insane."

They took out an advertisement with two of Duke's photos, giving Father Vasanthan's contact information in order to dissuade chances of spurious claims. They met the newspaper's founder E. Saravanapavan and Anna told her story once more. Saravanapavan forwarded Duke's picture to someone he knew in Germany.

After the visit to Uthayan, the group broke for lunch. Amarnath told Anna that he would post Duke's photo to online news sites in Toronto, while Father Vasanthan would pass the photos around in other parishes.

A Breakthrough

The advertisement was black and white, printed on the side of the seventeenth page.

Anna saw people waiting at roadside stalls and standing outside their homes reading the newspaper. She hoped someone would recognize the photo and call. In a small town called Puthukkudiyiruppu, the group visited another Catholic priest who talked about the many challenges faced by the people of his community, ranging from issues of child abuse to prostitution. At another town called Putumattalan, they saw remnants of a blown-up school that was used as a makeshift hospital towards the end of the war. All that remained standing were parts of cement walls. There were still medical supplies strewn about the rubble. A new school was being rebuilt on the same spot, and the group met a few of the students. On the way from Putumattalan to Amarnath's home in Mullaitivu, they stopped by a hospital. Although the area had been a designated safe zone, doctors claimed the building was bombed during the final stages of the war by the Sri Lankan army. The claim was denied by the Sri Lankan government.

On the way back to the van, Father Vasanthan got a call. The woman was calling from Germany. She identified herself as the sister of the woman in one of the pictures of Duke.

Father Vasanthan put the call on speakerphone, with Amarnath and Kumaran huddled around. Anna looked on, bewildered, unable to understand the conversation going on in Tamil. When Anna tried to ask questions, the others shushed her. The woman in Germany remembered Duke as one of her husband's friends, but her husband now had dementia.

Suddenly, Father Vasanthan said a name: Manipay! He was repeating what he was hearing on the phone, making sure he got the name right. It was the name of the town that Duke came from. The group couldn't believe their luck.

Manipay

Manipay is a smaller town in Jaffna, about a twenty-minute drive from the downtown core. The group started their search with the local Catholic church. The priest there didn't know anyone by the name of Sathusigamani Pillai, and the name didn't turn up in the baptism records either. But the priest called the caretaker of the church, who recognized the last name as that of a man he used to work with at a cement factory, who was now dead. The priest told them to visit an old woman in the village, who knew all the families in the '80s. It was a long shot, but the group decided to take a chance.

When they arrived at the woman's house, she wasn't there. About to turn around to leave, they noticed an elderly woman walking towards them. She invited them in. When Kumaran explained why they were there, speaking to her in Tamil, and told her Duke's last name, the woman smiled.

Kumaran says they knew the woman knew something. "You could just tell, the way she had smiled. I was sure she knew exactly which family we were talking about. But we couldn't do anything. She said she didn't know and asked us to leave, so we left."

At that point, Anna told herself it was over. But the rest of the group persisted. The tuk tuk driver took them to a Hindu priest he knew. The priest's mother told the group to try the village doctor's house since he knew everyone. Anna stopped herself from rolling her eyes, and the group made their way to the doctor's house.

As they stopped to ask for directions, Amarnath noticed an old man slowly cycling down the road. He told Kumaran to ask the old man if knew the family name. It turned out that he did know the family, and where they had lived. For Anna, the old man, Mahendran, was like an angel on a bicycle. Amarnath says that's how villages work. "You want information, you find the old people."

Mahendran led the group to a big house with a bright blue gate. The ladies who owned the house didn't have any information but Mahendran took them to another house a few doors down. The couple living there knew the Sathusigamani Pillai family quite well, even their son, Duke.

They pointed them in the direction of the house of a relative who lived a few blocks away, and the group rushed there. The houses in the neighbourhood had brightly coloured boundary walls, sloping, tiled roofs, barred windows and an entrance decorated with potted plants. The group found themselves knocking at an elaborate gate. A woman in a sleeveless dress appeared before them, her hair down, a puzzled look on her face.

The woman's name was Sitha. She invited the group in and told them what she remembered about Duke. The living room was filled with wooden cabinets and display cases, a family photo hanging on the wall. They sat around a coffee table, Amar and Kumaran talking to Sitha in rapid Tamil as Anna smiled.

Duke was one of eight children; he was naughty but studied well. Given Sri Lankan Tamil cultural traditions, Sitha could have been engaged to marry Duke. And she told them about one of Duke's sisters, Sarojini, who didn't live too far from her house. Duke's mother also lived somewhere in Jaffna District.

As she left Sitha's to find her aunt's house, Anna couldn't help crying.

Anna thanked Mahendran, who also had tears in his eyes, and wouldn't accept any money.

At Sarojini's home, introductions were a little more abrupt. Initially, Sarojini and her husband were perplexed to be introduced to Duke's daughter, as they knew he had not married. Anna's uncle said he'd seen the ad in Uthayan but was confused because it had mentioned a daughter searching for relatives. Again, Anna couldn't understand most of the conversation in Tamil, and Amarnath and Kumaran translated.

Although the aunt and uncle welcomed them, and answered their questions, they looked guarded. Anna found out that one of Duke's brothers had died. Sarojini's husband told her that he used to take Duke to the movies, that he was a patient young man, but also got into some trouble. He also told the group that Duke had been sympathetic to the LTTE and had been interrogated and beaten by the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). Sent to Sri Lanka in 1987 to disarm the militant outfit, the IPKF found itself embroiled in the conflict, and has been accused of human rights violations in the course of its operations.

When Anna asked if they had any pictures of Duke, they showed her one where Duke looked bigger but was wearing the same green shirt that he wore in the picture that Anna had. She also saw a painted portrait of her grandfather. The couple wasn't in contact with Anna's grandmother, they added, and suggested that she might disown Anna given that Duke was not married.

Throughout the meeting, Anna felt as if she was causing some trouble by being there. Still, her aunt hugged her several times, with tears in her eyes.

The group grabbed lunch before setting out to find Duke's mother.

Answers

Duke's mother Gunalakshmi lived in Valvettithurai. Sarojini hadn't given them many details or an address. The group asked around, stopping passersby on the roads, but they weren't getting anywhere. They asked at a convenience store, but no luck. Then they noticed an old woman sitting outside her house. At first, they asked the old woman if she knew where Gunalakshmi lived. The woman said no. However, based on a photo that the aunt had given them, Kumaran and Gurvinder were convinced that the old woman was Gunalakshmi herself and started accusing her of lying. Meanwhile, another woman approached them. She had heard about their search for Gunalakshmi and offered to take them to Gunalakshmi's house.

They took a winding path, through a house and long backyards. When they reached the house, an older woman came out. They asked if she was Gunalakshmi, Duke's mother. The woman started crying and said yes.

The group went inside and arranged some chairs in a circle. Kumaran asked the woman if she knew that Duke had children. Gunalakshmi told the group that Duke had told her he had met a white woman. Kumaran pointed to Anna and told Gunalakshmi that she was Duke's daughter.

When Anna took out Duke's picture, Gunalakshmi got up to get out her glasses. She burst into tears. For the next two and half hours, Gunalakshmi talked to them about Duke.

Gunalakshmi told Anna that Duke was named after one of his father's European friends. That he was handsome and got into a lot of trouble, loved school and wanted to be an engineer. He was the baby of the family. He had been affiliated with the LTTE for three months and was shot by the IPKF. Fearing for her son, she had faced off with one of the main leaders of the LTTE, Colonel Kittu. He was known for his fierce loyalty to the cause, and his ruthlessness. He told Gunalakshmi that Duke couldn't escape his association with the LTTE, that he would get killed either by the LTTE or one of their enemies. Gunalakshmi told Colonel Kittu that if she could not save her son, she would shoot him herself.

Gunalakshmi had Duke shipped off to Colombo, and then to Germany. Every six months, she'd travel to Colombo to place a call to him. Then one day, her older son stopped her from travelling to Colombo. News had come from Germany of Duke's death.

Anna's grandmother turned out to be a feisty woman, who had decided to live by herself to avoid squabbling family members. During the group's visit, she was cracking jokes, questioning Kumaran's marital status and attributing Amarnath's shaved head to his kids. She asked Anna if she had a lover; when Anna pointed to Gurvinder, she told them that they'd better be married when they came to visit her next.

It was turning into evening, and the group had to head back to Jaffna. Anna and Gurvinder had to fly to Colombo the next day, and then leave for Canada. Anna and her grandmother hugged several times, as if unwilling to let each other go. Anna felt Duke in Gunalakshmi's arms. She told Gunalakshmi that she would learn Tamil, and promised to write and send photos, and come back to visit.

The group had a celebratory dinner at a restaurant back in Jaffna. The driver remarked that what had unfolded that day only happens in movies.

Last Days in Sri Lanka

The night before Anna and Gurvinder's flight out of Jaffna to Colombo, Anna barely slept. She kept waking up with a start, not believing what had happened.

Their last day in Jaffna was a beautifully sunny one. As Anna and Gurvinder said their goodbyes to Amarnath and Kumaran, Anna struggled to express herself.

After the flight that took them over the lagoons and coast of Sri Lanka, Anna and Gurvinder made their way to a friend's home in Piliyandala. That's when Anna called Maria.

Their conversation was awkward and distant. Anna remembers answering Maria's questions about Duke and his family dispassionately. Maria doesn't remember asking any questions at all. Anna still could not believe that her mother didn't have more information that could have helped in her search.

Anna and Gurvinder spent their last day in Sri Lanka walking the beach at Galle Face. After a quick trip to shop for souvenirs, they were headed to the airport. During the drive, Anna felt a sense of peace. She was leaving with answers she had only dreamed of having.

Afterthoughts

Sitting in his living room, Woody says it was a miracle that Anna managed to find her grandmother in Sri Lanka. After living for so many years with so many questions—about Duke, why he had ended up in Germany, why he died—Anna had found some answers. She had strangers helping her through some of her darkest moments.

He uses the word miracle again, this time to describe Anna herself. "Anna is like the glue for the family. She's the fire extinguisher because sometimes our family is almost like a bomb," he says. He pauses for a few minutes and looks outside the glass doors of his living room. His eyes are glistening when he turns back, and he asks, with a catch in his voice, "Do you think I'm a hero?" His question about his decision to acknowledge Anna as his own child is rhetorical. "No. I'm not. I don't think I did anything special. I wouldn't have been able to look myself in the mirror."

"Our life is like karma—whatever you do comes back to you, or sometimes even harder. Everyone makes mistakes."

Maria maintains that she didn't know much about Duke's history other than what she had already told Anna. Maria and Anna are on better terms now; Anna's marriage to Gurvinder in the summer of 2018 brought the family together for the wedding celebrations. But Duke remains an unresolved issue between them. And Maria felt disappointed by Anna's estrangement.

When Anna went to Sri Lanka, Maria says she was scared for her daughter. She was unsure whether Duke's family would accept Anna. But Maria says, "I believe in the power of the dead. I was sure Duke would look after her."

There's no question in Anna's mind that she needed to look for Duke in order to find herself. When she tells the story, there's always a reaction of disbelief, as if something magical happened. There's some truth to that, Anna says.

"Yes, it was a magical experience. But it was also very difficult. In a way, I didn't have that fairytale ending. If someone were to read this story as inspiration for whatever their search may be, I would say that you may have questions, and all you can do is try to find the answers."