“As individuals, we derive our sense of selfhood from shared values that are, in turn, embodied in public institutions. When those institutions change, those changes reverberate within us: they can seem to endanger the very meaning of our lives. It's partly for this reason that events in the political world can devastate us so intimately, striking us with the force of a breakup, or a death.”

- From “How to Restore Your Faith In Democracy,” by Joshua Rothman, The New Yorker

1.

In May 2015 during the Victory Day events that marked seventy years since the end of the Second World War, I watched Stalin's grainy portrait float above a crowd, marching out of sync along a central Moscow boulevard, suspended in the air by two hands. Military medals gleamed on his sepia chest, and similar regalia caught the still-weak spring sunlight from the Soviet-made overcoats of some of the marchers. They were mostly older: white-haired men in pork pie hats and women in thin kerchiefs and overcoats too warm for the weather. But younger Russians were there too, a T-shirt printed with a political slogan—“For the Fatherland, for Stalin”—peeking out from underneath an unzipped jacket here and there. The mood of the procession was like the sunny spring morning: happy and defiant. And Stalin's bushy moustache smiled down like a grandfather telling his favourite grandchildren a bedtime story.

I had been away from Moscow for half a decade when I returned that spring, and Stalin was back in public life in such an ordinary way that I felt like a tourist if I gaped: at the portraits of him in the newspapers, on TV, in newly published biographies, and stenciled on T-shirts and graffiti. No one else seemed to notice or mind. Most people walked past without looking.

Five years earlier, the sight of a fridge magnet with Stalin's face on it in my extended relatives' kitchen had made me miss the next thread in our conversation. As I sat there, at a kitchen table across from a cousin I had spent summers playing with, and his parents, I tried to connect the image to the rest of the room: the cozy lighting, the tulle curtains, the wooden bread box. Half a century had passed since the 1956 speech titled “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” knocked the great Generalissimo's statues from their plinths across the USSR. The speech, delivered by Khruschev, the man who would succeed Stalin in leading the USSR, established the Stalinist period in Russian memory as a time of abusive one-man rule. Sitting with my relatives at their kitchen table that winter evening, I didn’t ask about the portrait. We hadn't seen each other since spending our last summers together in my mother’s hometown, before my parents and I emigrated to the States in the mid-1990s, and I knew that the kitchen table separating us was an ocean.

In the five years it took me to return to Russia, something there changed. In 2010, visitors would have been hard-pressed to find any references to Stalin in public. But by the spring of 2015 when I arrived to find out why that fridge magnet with Stalin's face on it in my relatives' kitchen would be far from the last one I would see, it was as if Stalin had never left. In a way, he hadn't.

A famous Russian stand-up comedian likes to quip that Russia has an unpredictable past: one where a political leader can be God one year, tyrant the next, only to be revived years later as an “effective manager.” Extraordinary as it may seem, Stalin's 21st-century comeback is so ordinary that it's almost on time, like a train. It is a story about Russia's relationship with the Second World War, with authority, and the legacy of the Soviet Union. It is a story of how ordinary people react to loss—of identity, security, dignity—and to shame. How people interpret their past after their world has been smashed to pieces; how they put those pieces back together.

2.

To tell the story of why Stalin is back as a positive historical character in Russia, I have to tell you about my family.

If this was a different story, I would tell you about how the 20th century steamed back and forth across Russia like a runaway train. I would tell you how it came to be that the word demokratiya in Russian doesn't quite mean democracy in English, how svoboda doesn't quite mean freedom, how the words have developed shades of darkness and cynicism that their English translations fail to convey. I would tell you about how when my mother and I were waiting for our visas to join my father in the United States in 1994, I imagined him making a million dollars a day because America was so mythologized, so otherworldly, that it might as well have been a different planet. (One where different sections of grocery stores had their own climates and apartment buildings had their own pools.) I would tell you about how, after we moved, I fought with my mother all the time because our lives unfolded planets apart. I would tell you about my careless school days in Canada reading Kerouac, when I believed freedom to be something I had to win from my parents, how after one of our arguments, my mother told me that what I was looking for didn't exist. “Svoboda doesn't exist.” And when she followed that with, “you will always be responsible for somebody,” I wouldn't know for another decade that she was right. I didn't know then that no matter how Canadian we became, we would never leave behind Russia's 20th century hold over us.

3.

My mother's side of the family comes from the fertile Russian southwest, from a stretch of land that was first occupied and then demolished by the cannonball tennis match of the moving front line during the Second World War. It is a small, provincial place of 40,000 people on the bank of a shallow river, near Kursk, where in 1943 the biggest tank battle the world has ever seen was fought.

The town's main street, like almost every main street in every town across Russia, is named after Lenin. It is lined down the middle with birch trees and wooden benches, where young couples and elderly neighbours sit together after dinner. It ends at the drop to the riverbank, at the town's central square where the children's park meets the World War II memorial.

After my mother's father returned to this town in 1945—after he had spent three years in a German concentration camp as a Soviet prisoner—he and my grandmother built their one-story wooden house a few streets away from the town centre. They built it down an avenue named after the founder of the Soviet secret police, Dzerzhinsky, on a street named after a 19th-century Russian poet, and painted it forest green. Like everyone else on the street, they built it the same way that people there still build their houses: with an allotment at the back for growing vegetables and raising chickens because the war had taught people to rely on themselves. That house is where my mother grew up in the 1960s and the 1970s, where she left when she went to Moscow to take her university entrance exams, and where I spent my summers chasing chickens and playing war games with my cousins while my parents were working on their PhDs at Moscow State University.

Before my grandfather died, before my parents and I emigrated, I would pester him to tell me stories about the war. Most often, he’d avoid the subject. He had been taken prisoner that first winter, in late 1941 at the age of nineteen, fighting under Stalin’s Red Army banner. Pictures from before the war show a strikingly handsome man with an attractive wave in his black hair, full lips, and a wide smile. When I knew him almost half a century later, he was still handsome, with gleams of silver in his teeth and a quick, cheerful step; and he liked to joke. Like when he played hide-and-seek with me, he would always pretend to misunderstand the rules and instead of hiding, he would obscure his head behind a curtain like an upright ostrich, leaving the rest of his body for me to find. No one other than his wife knew about his unpredictable temper.

When I did get a story out of him about his time in the camps, it was always one of three or four that he told and re-told: each of them about hunger. About how guards had given him and the other prisoners animal hides to sleep on and how the prisoners had gradually eaten them over a winter instead. How he had sewn a potato he'd stolen into the pocket of his trousers before giving them to the guards to be boiled as a way to kill lice. (“The human body can only absorb cooked potato starch,” he told me.) How a guard had caught him with the stolen, cooked potato, but instead of dispatching him into the next world then and there like my grandfather had expected, the guard had chuckled and clapped him on the shoulder, called him smart.

These stories were enough for me to swap with the other kids on our street, all of whose grandparents had been through the war themselves. But not until after my grandfather's death did I realize how little I, or anyone else in my family, know about his life in the 1940s. He had told memories of the war like he played hide-and-seek, showing only the parts he wanted us to see. The Russian approach to history.

On my father's side, my great-grandfather, who lived to see the sixtieth anniversary celebration of armistice and died in 2009, fought on the eastern front and lost hearing in his left ear after a shell exploded in a trench next to him. After he enlisted, his pregnant wife and toddler son boarded an evacuation train to eastern Siberia. Three weeks later, in December 1941, my great-grandmother went into labour. She was taken off the train in a remote railway outpost and gave birth to a daughter, outside, in -40C weather, in a horse-drawn cart on her way to the nearest village. The baby immediately caught pneumonia. Certain that she would die, the elderly woman who helped deliver the baby comforted my great-grandmother, saying she was still young and would have other children. But the baby, my grandmother, had entered the world still wrapped inside her amniotic sac—a Russian omen for luck. It tipped her into the world of the living.

Stalin never figured in any of these stories. In the Russia of the 20th century, my family members knew instinctively that politics were dangerous. What a family member did before 1917, whether a relative had emigrated, whether they had ever had trouble with the Soviet authorities before the 1960s thaw: that information, in the wrong hands, could all cause trouble. So my family members kept to themselves, limiting political participation to walking in their schools’ and unions’ annual parades—for Victory Day, Labour Day, Women's Day—holding banners adorned with Stalin's name and image. That is, of course, before Khruschev's personality cult speech saw those images locked away and destroyed.

We didn't talk about the past. So much so that when, over the past few years, I started asking which camp my grandfather had spent time in, everyone had a different answer. The truth is no one knew. The memories did, however, make themselves known in other ways. Like when, in moving from the green wooden house in her old age to the nearby city to live with her oldest daughter, my grandmother discovered a bundle of my mother's letters in the attic: old telegrams, postcards from childhood friends, love letters, bits of life lived. She burned them all in her wood stove without giving it another thought, carried by a decades-old instinct to destroy all links to the past. My mother was devastated.

There was also that time in the 1970s, when on a visit to Moscow with his family, my grandfather stopped to give a lost East German tourist directions. Until that moment, no one knew that he spoke German.

4.

If it was possible to put a date on when Stalin returned as a positive historical character in 21st-century Russia, it could be 2009, the year Stalin's grandson Evgeny Dzhugashvili sued the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta for libel after it called his grandfather “a bloodthirsty cannibal” in a story.

The story referred to Stalin's role in an infamous historical massacre in 1940, when firing squads executed 20,000 Polish prisoners in the remote Katyn forest in southwestern Russia. The shootings took place at night, over severals days. And for fifty years, the Soviet leadership had blamed the massacre on Nazi soldiers.

In the late 1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev accepted the Soviets' role in the killings, saying that the Soviet government—and Stalin himself—had given the execution orders. It was perestroika, and history was once again up for discussion, and what had previously been only guessed about could finally be investigated and discussed. Early-1990s TV programs, one after the other, seized upon the excavations at Katyn and other secrets involving Soviet rule, upon crimes of the Stalinist period.

But by 2009, in a sign of things to come, Dzhugashvili was to be found arguing that when Novaya Gazeta published the story about Stalin's role at the Katyn massacre, it not only based its account on false evidence but was working against Russia “to make it weaker.” He was demanding a retraction, a public apology, and ₤180,000 in damages for defamation.

The journalist who wrote the story, Anatoly Yablokov, said a suit like Dzhugashvili's would have been unthinkable in the past.

“There is a change in society's view of Stalin,” he said at the trial's preliminary statements in 2009. “We hear much more now [than in the 1990s] about what an effective manager Stalin was and much less about the repressions.”

That year, Moscow city authorities restored prominent Stalinist-era lettering the city had erased more than half a century earlier in the vestibule of one of Moscow's busiest metro stations. The lettering says, Stalin reared us on loyalty to the people. He inspired us to labour and heroism. By 2012, 45 percent of Russians seemed to agree, saying that they had a positive view of Stalin in response to a Levada Centre poll. By March 2016, 54 percent agreed.

It was at the European Court of Human Rights—an ironic venue considering Stalin's human rights record—that Dzhugashvili lost his final appeal in early 2015. The court ruled against Dzhugashvili's libel suit and said that a historical figure such as Stalin would “inevitably remain open to public scrutiny and criticism.”

And open he remained. In 2016, a string of museums opened to commemorate Stalin's contribution to Soviet and Russian history. A “Stalin cultural centre” opened in Penza as a direct response to a "cultural centre" celebrating Yeltsin opening in Ekaterinburg the year before. Another museum, near Tver, 200km west of Moscow, commemorates a night Stalin spent there in August 1943, near the site of some of the war’s most devastating battles. Its fourteen panels memorialize feats such as “Stalin's contribution to victory” in the Second World War, “Stalin's role in the restoration of the Russian Orthodox Church” (reopened during the war to lift morale) and “Stalin As the Symbol of Soviet Successes and Victories.”

In Moscow, the only remaining statue of Stalin stands abandoned in the graveyard of former Soviet relics, its nose missing, amid dozens of busts of Lenin and a statue of the founder of the Soviet secret police. But across Russia, town councils have debated erecting new statues to him in their public squares. So far, only one has gone up—in Crimea in 2015.

That monument shows Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at the Yalta Conference in 1945, ten feet tall and seated together to decide Europe's future, months away from Germany's capitulation. Behind them are five years of destruction: cities destroyed and villages wiped off the earth, millions of refugees across five continents, populations decimated. In the Soviet Union alone, where the meeting took place, 20 million people were dead, out of the 40 million people killed across the world in the whole of the Second World War. In Belarus, a quarter of the population was missing, never to be seen again. But at Yalta, the troika sat victorious, Stalin the only one of the three wearing military epaulettes.

5.

A few months after that conference in Yalta, my maternal grandfather returned home to a pile of rubble to meet his future wife and build their green wooden house that would be my mother's—and later my—home. He was the only one among the adult men in his family to survive the war.

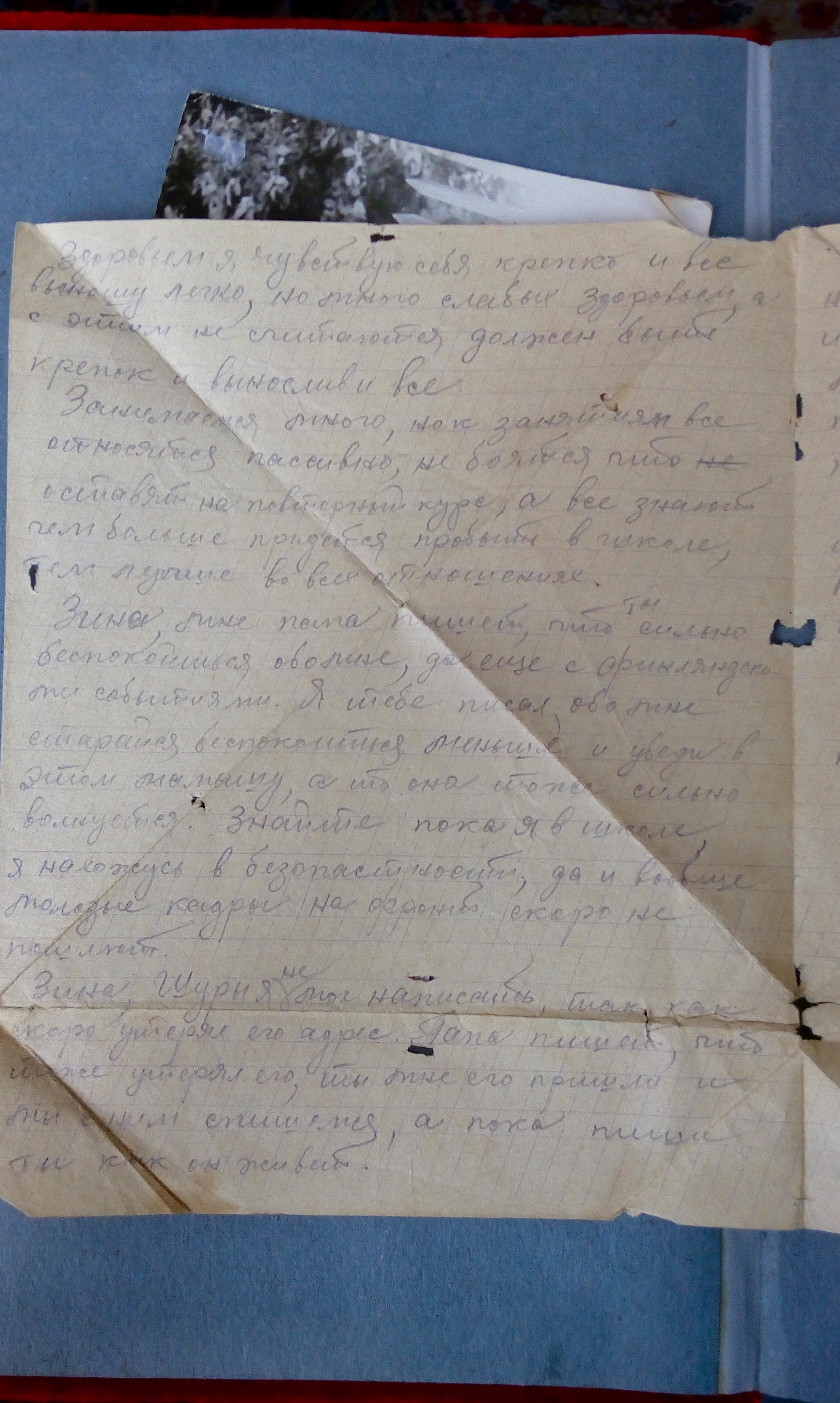

There is a reason why so many public memorials to Stalin, like the one in Crimea, in Tver, in Ekaterinburg, and Penza, connect Stalin's name with the Second World War. It was the most traumatic event in Russia's contemporary history and Stalin was its wartime leader. The numbers of people killed across the USSR suggest that, like my family and the families of my childhood friends, every Russian family was affected. The record is in the boxes of black and white fading photographs stored in closets across the country, underneath beds; in the letters wedged between them, breaking at their creases, along the folds of tell-tale triangles from a time when paper rationing forced people to improvise envelopes out of the letters themselves.

People born outside of Russia might wonder: for all the devastation, how could Russians be willing to forgive so much of Stalin's wartime leadership? Because, the argument goes, had it not been for some of Stalin's most devastating policies—among them the forced industrialization drive in the 1920s and 1930s and the collectivization that drove millions to their deaths in the 1930s, especially in Ukraine—the formerly agrarian Soviet Union might not have been able to withstand the German army. And what then? the argument goes.

Over the past decade, the Russian government has funded military parades and school programmes looking into wartime family history, built a World War II historical reenactment park for children near Moscow, funded hundreds of volunteer search crews that go out every spring and summer to search old battlefields for the remains of some the four million Soviet soldiers—four million people—who are still officially listed as missing in action in the Second World War. The crews look to reconnect their remains with their families, and almost every expedition is successful. The state has invested millions upon millions of rubles in ever-bigger Victory Day parades every year, on fanfares, salutes, concerts, and fireworks to remember the World War II victory.

The Russian president says: “We must be proud of our history.” And so, amid all the dying, Russia's official history of the Second World War is a history of glory. The war stands on its own, absolved of what came before or after. It is not related, in textbooks or popular consciousness, to the show trials and summary executions that came before, nor to the mass incarceration in the gulags, nor the man-made famine in Ukraine. Victory in the Second World War is like a badge of honour, a foundational myth that Russians can unify around. The story lands exactly because no Russian family was spared, because every school child can connect it to family history. But when official history remembers the heroic visit by Stalin to the front near Tver in 1943, it forgets—among other things—that that visit was the closest Stalin came to visiting the front; that the visit came nine months after fighting in the area had ended.

The Russian government exploits wartime memories to create a glorious national story: we were strong then, we are strong now. We need strong leaders to withstand our enemies. The stories the government tells might be in service of its own goals. But that doesn't erase the fact that the people in the black and white faded photographs are real. That until recently, some of them sat at our kitchen tables talking about relief planes dropping packages of bread from the sky; hoarded jars of food in the pantry. Just in case.

In 2006, Russian activists created a new commemoration ceremony for May's Victory Day events. The Bessmertnyi Polk (The Immortal Regimen) ceremony immediately sparked similar yearly tributes across the country. At the closing of Victory Day events, millions of people now walk in a procession holding pictures of relatives who fought or died in World War II. For the seventieth anniversary of Victory Day, the Russian president Vladimir Putin joined the procession, walking through Red Square with a picture of his own father, a veteran. We can talk about exploiting memory for political gain, but it's hard to argue with that sacrifice of the people in the photographs, what they went through. Millions of old black and white portraits, held up in collective memory, across the country. It's a moving commemoration. And one at which Stalin's portrait appears often.

6.

Another thing about understanding Stalin's comeback—and this will surprise many people who grew up in “the West”—is that the Soviet Union wasn't all bad.

When my parents were students in the 1980s and early 1990s, we lived in a skyscraper that was, until 1988, Europe's tallest structure. It was completed in 1956 and designed on Stalin's orders as a monument to the glory of the Soviet state, in an architectural style now identified with High Stalinism. It was the Moscow State University Main Building.

My parents had both travelled to study at MSU because it was the best educational institution in the USSR. They met, married, and like many of their friends had their first child while still living in residence. We lived in the north wing of the building, on a floor for families, where toys and tricycles lay scattered outside the elevators and small children roamed the hallways in packs.

That Stalin's biggest architectural project was a university is not an accident. From the very beginning, education was a matter of survival for the Soviet state.

One hundred years ago, almost all of my family members lived as peasants on estates that their grandparents had tilled as serfs, and were almost entirely dependent on their masters. A hundred years ago, almost everyone in my family was illiterate, because on the eve of the revolution in 1917, of all Russians, only 40 percent could read and write, including only 13 percent of women. How well can a country of farmers fight off an invasion? Lenin and Stalin's push to educate the masses began almost immediately.

The state mandated universal primary education and funded everything: primary schools, universities, vocational colleges. It funded daycares so that women too would benefit. By the Second World War, the compulsory education programme had pushed the literacy rate to 90 percent.

After my mother left her small town and defied all the odds in passing the entrance exams to the best institution in the country, there was nothing stopping her from pursuing any education she wanted (as long as she kept her grades up). In return for a free education, graduates agreed to work for three years in a placement, which could be a remote town anywhere in the USSR where there was need for their skills. But once accepted, few material problems could come between students and their ability to get an education. And when my mother left her hometown for MSU, no one forgot that her own grandmother, born in 1907 in Moscow, had never learned to read.

My father grew up in a small northern town on the Volga, sharing an apartment with his single mother, a music teacher—the same woman who some thirty years earlier had been born in a horse-drawn cart in -40C weather—and his grandparents, also both from tiny northern villages. After getting interested in photography in high school, my father became desperate to get his hands on the solution necessary to develop colour photographs. But in the late-1970s USSR that was well-known for its shortages, he could not find a single store that carried the chemicals he needed. He checked out all the chemistry textbooks that might help him to find a way to mix the chemicals himself at a library. Soon, he was competing in regional and then country-wide chemistry Olympiads—all state-funded—and admitted to the best university in the Soviet Union, in Moscow, without the formality of mandatory exams. He was one of a handful of students for whom the university waived the requirement.

This is what we know: my parents were among the best students in their districts. Neither would have gone to university had it not been state-funded.

A seventy-five-year-old woman, Marina Viktorovna, who I met at the Moscow office of Memorial, the Russian human rights NGO that works to collect records on people who were politically persecuted during the Stalinist period, told me: “If we think about it, at its heart, the Soviet project was right.” This, coming from a woman who was at the office to consult her “file”: the documents she had collected over the last decade about what happened to some half a dozen members of her family, who had all either spent decades of their lives in the gulags or in exile, or been the children of those who did—all for the vague crime of “sabotage” to “restore the capitalist order.” Even half a century later, Marina Viktorovna would not tell me her last name. Viktorovna is her patronymic—Russia's version of the middle name. Having a family history in Russia, it seems, is still uncomfortable.

The USSR had its problems. But after two decades of “economic shock therapy” in the new Russia, the USSR is looking better and better.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, my mother had already defended her PhD and was working as a researcher and chemistry lecturer, while my father worked toward his own thesis defense. But all of a sudden, her academic's salary was barely enough to cover her metro fare and canteen lunches. Prices were floated on the new, open market, they flew away like balloons. Academics and other publicly funded employees had little hope of surviving in the new market economy. This was the time of picket lines outside schools, universities, and hospitals, employees at their wits' end over months of withheld pay because no one was really sure who owned and was responsible for what; and breathtaking crime. The programming job my father accepted instead of finishing his PhD meant that we were alright. But if my mother bought a bag of groceries over her lunch break—eggs, juice, cottage cheese—under her coworker's gaze the bag radiated like it was stolen.

But with my father's income, we bought jeans. We visited the first Western grocery stores where shelves were so plentiful that the store offered customers a basket to carry their yogurt, hazelnut spread, tropical fruit juice, and European cheese; we chewed gum and bought Snickers, cutting the bars into a dozen pieces to share for dessert. (I was five when the chocolate bar ice cream commercials appeared and still can't walk past a Mars ice cream bar without getting sentimental about the miracle of consumer capitalism.) We watched Mexican telenovelas dubbed in Russian and lined up for hours outside of McDonald's, in a queue that zigzagged Pushkin Square in central Moscow, while entrepreneurial Muscovites stood queue-side, selling everything from pantyhose and used electronics to kittens and pet turtles.

Around the same time, luxury SUVs began to appear on Moscow streets: leather seats, tinted windows, always the sleek black exterior. Commercials appeared on television and quickly took over more airtime than TV programming. The most frequent commercials seemed to be for the panoply of banks that spouted like mushrooms. There were so many new banks and so many commercials for banks and the banks opened and folded so frequently, swindling their customers so often in the process, that the tagline of one commercial simply said: “We won't cheat you.” It showed a woman taking money from a teller, beaming, and telling the camera: “They didn't cheat me.”

In the first decade of post-Soviet Russia, it was common to hear people quip that if in the Soviet Union they had money but nothing to buy with it, now all they ever wanted was in a store around the corner, but they had no money.

“Economic shock therapy” came with a price, and in the “end of history” euphoria that swept North America in the 1990s, few realized that after the Soviet collapse, there have been 2.5 million “excess deaths” in eastern Europe: mostly as a result of poverty and its malaises, like alcoholism, which caused a drastic lowering of life expectancy in Russia—from 63.5 for men in 1991 to 58.6 ten years later. Whatever optimism people still had for liberalization plunged along with the ruble in the 1998 default. Millions of people—like my paternal grandparents—lost their savings overnight, years of work reduced to worthless bundles of paper.

The overwhelming feelings of the 1990s were bewilderment and shame: at the crime, the poverty, at the luxury SUVs with their oblivious tinted windows. The drunken president making the country the laughing stock of the world. In 2001, economist Steve Keen wrote: “Russia's free market experiment and crash of economic liberalization may have done more to rehabilitate Karl Marx—and even Joseph Stalin—in the eyes of the average Russian, than anything positive done by Russia’s socialist camp.”

It was around this time that words started to shift in meaning. We were promised a better life—why are we poorer and more insecure than ever? The words “market economics” and “liberalism” became tinged with resentment. Slowly, they grew to be associated with deception. The feeling of resentment infected other words too: democracy, freedom, human rights. “What's freedom?” people would say. “Is it the freedom to hit bottom?

The new millennium brought in Vladimir Putin, who saw a Russia desperate for stability and positioned himself as a strong leader. By 2005, he was calling the Soviet collapse “the biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.” He reminded us of how we won the biggest war the world had ever seen, and how we would not be cowed now.

And people said, “well, at least it's not so shameful to be Russian now.”

And they thought, the invisible hand didn't work for a lot of Russians—would a strong one? An iron one?

7.

“I'm sick to death of the portraits of Stalin at public gatherings,” says Yan Rachinsky, one of the founders of Memorial. “But what's more dangerous is that the old [Soviet political] order is coming back. The idea that everywhere around us there are enemies. That's a persistent Stalinist idea. The 'fifth column' and 'foreign agents'—all of that is terminology from Stalinist times. Without the repressions, a large part of the context of that era is coming back.”

When newspapers or neighbours talk about Stalin as a strong leader rather than an autocrat, a dictator, Marina Viktorovna doesn't respond. “The war touched every family,” she says. “And with repression, it's the same thing. But few know about that." She understands people who want a strong government—and that's what she hears when she hears people talking about Stalin as a strong leader.

“I understand people want an iron hand to come and clean everything up. They never think that that hand can hurt them.”

In 2016, an instructional manual for high school history teachers on how to teach the Stalinist period—how to talk about the scope of forced labour, the disappearances, the sentence of “ten years without right to correspondence” that people found out later was code for death—was banned. Authorities said that the manual's instructions were destructive for students, that it could weaken their “disposition for sacrifice.” The idea seems to be that some repressions are necessary. Don't question them: that in itself is a threat to the present order. Like the Dzhugashvili case showed, people perceive criticism of historical decisions as attempts to weaken Russia. A Western ploy, propaganda to make the country weaker, make it collapse like the Soviet Union. The president reminds us: we must be proud of our history.

After I moved to North America as a child in the mid-1990s, I learned that I was less interested in the story and more interested in the way it was told, which parts were included.

In Russia, history lessons taught me about: grandfather Lenin, Russia's vast boreal forests, Pushkin. After we moved to the States, Lenin became George Washington and the apple tree. Pushkin became pilgrims (and Indians, this being the mid-1990s) and Thanksgiving. And when my family moved to Canada at the end of 1996, history lessons were less about socialism and the Second World War than Sir John A. MacDonald, Louis Riel, and the Northwest Passage.

I learned that when people talk about their past, they are talking about their future. When the Russian Ministry of Culture erects a statue of Ivan the Terrible in a town he conquered five hundred years ago to expand Russian land south, and the monument shows him on a horse holding the Orthodox cross aloft, that is a message that the Russian state considers it important to tell a story about defending the Orthodox faith on lands that it has claimed to be Russian. When Poland and Ukraine ban communist symbols from public view—Soviet statues, monuments, images, that shows that they want to leave behind that part of their history, to see it as an historical aberration, unlike the non-Soviet part of their history. The Rhodes Must Fall movement aims to show how much history dismissed the stories of the conquered. The same can be said about the move to depict Harriet Tubman, women, minorities on American currency, all of whom have been dismissed from the visual memory of public monuments.

Canada's former prime minister Stephen Harper worked to refocus Ottawa's museum of civilization—that aims to tell a story about Canada's history—to Canadian military history. He commissioned a memorial to the victims of communist oppression near the justice buildings in Ottawa.

Last year, Gabor Mate, a well-known Hungarian-Canadian doctor and public speaker who has earned the right to dislike communist rule—being born as he was in Soviet-occupied Budapest in the 1940s—wrote an op-ed against the Ottawa memorial. In it, he argued that the project uses the stories of people who suffered under Soviet rule to advance a political agenda.

He writes: “What is the principle here in service to which public space is to be utilized and public money spent, if not to advance Tory ideology? Is it to honour humans destroyed by power-mongering, aggression, greed and cruelty? That would be inspiring. Let us then erect a monument to the victims of industrial civilization, Communist or not.”

He goes on to list the people who would be memorialized: the millions who died in the Stalinist purges and gulags, in the Ukrainian famine, the Chinese who starved to death in wake of Mao's Great Leap Forward; the Magyars killed battling Soviet troops in Budapest; the millions of Congolese murdered by Belgian diamond hunger; and the three million Vietnamese slaughtered by the US in the name of anti-communist containment; the many tens of thousands hounded to death throughout Latin America by American-backed regimes over the decades, the many millions of martyrs to racism everywhere. The hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people killed in North America to facilitate colonial expansion, “victims of Christian mercy at the hands of nuns and priests and other ministers of Western culture.”

Russia isn't alone in its “problematic” national myth. The slapstick speed with which Russian history can shape-shift, however, is striking.

The oldest and biggest museum to Stalin's memory stands in the centre of Stalin's hometown, Gori, in Georgia. Its entrance is a two-room wooden hut with scuffed floors and some of its original furniture, where Stalin lived as a child with his mother and father, a cobbler. Inside, it shows Stalin's life—as a young seminary student, a revolutionary on the run, leader of the USSR, sitting next to Churchill and Roosevelt as Yalta—in objects: pipes, books, letters, gifts leaders of other countries gave him, his death mask. The hut is ensconced in a Soviet-style monument, a temple to the memory of Gori's most famous son.

After the 2008 war in South Ossetia, the Georgian Minister of Culture announced that the Stalin Museum in Gori would be reopened as a Museum of Russian Aggression. An unusual banner was installed at the entrance saying: “This museum is a falsification of history. It is a typical example of Soviet propaganda and it attempts to legitimize the bloodiest regime in history.” The sign remained there for three years—amusing or aggravating visitors depending on their perspective—until 2012, when Gori's city council voted for the sign to be removed. The vote ended the showdown of historical narrative, and the memory of Gori's most elevated son stayed as it was.

In 2012, the Russian government passed a law that allowed labelling NGOs that receive more that 25 percent of their funding from overseas as “foreign agents.” (MPs aligned with Putin's party saw democracy-promoting NGOs in Russia as tools of Western political power.) Memorial itself was among the organizations branded a “foreign agent.” Its offices are often ransacked and its employees intimidated. Last year, the entrance to Memorial's Moscow office was spray painted with the words, “USA out.” In 2015, Perm-36—a former forced labour camp that activists opened as a museum in 1994, the only one of its kind in the country—was forced shut. Newspapers and state-sponsored Russian TV had derided its portrayal of the repressions as “worse than they were” and called the museum's leadership “the fifth column” (a derogatory term for political opposition). In 2012, the government pulled its funding and by 2015, the museum was forced to close.

8.

How do we tell both stories? It's like saying two opposite things at once.

Last fall I attended an event commemorating the 35,000 people executed in Moscow alone during Stalin's Great Purges in 1937-8. Memorial organizes the event every year on the day before a day of remembrance for victims of Soviet repression on October 30th. At the “Returning of the Names,” volunteers read the names, ages, professions, and dates of arrest and execution of people from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. Last year was the tenth anniversary of the event and organizers expected that by the end of that day, they would have read half the names on the list since the event began in 2007.

By noon, the queue of volunteers waiting to read from the bits of paper bearing the names was over two hundred people long. It was snowing and windy, and the ground was wet with sleet. People queued up to two hours for less than a minute at the microphone, to read names, some of which were well-known and others that had not been spoken aloud for over eighty years.

One man—in his eighties, short and thin, mistrust written into the deep lines of his face—took his turn at the microphone to speak his list of names. He read them and then began speaking about his father, who the police had taken away when the man was six years old. One of the officers who had come for his father had pulled him by the ear so hard that he thought it would come off, the man said, holding his hand to his ear. As he went on, breaking the rhythm of the procession, the crowd became uncomfortable. After a few minutes, one of the organizers walked over to stand next to the man. She gently touched him on the forearm, startling him. He pushed her off, gesturing to the crowd that she was interrupting, continuing to lay into Soviet history. The organizer let the man speak another few seconds, amusement and impatience written across the crowd, and patted him again on the arm, gestured toward the queue behind the man, said a few inaudible words. With the organizer now holding him by the arm and moving him off, the man swore at her but allowed himself to be led aside.

Moved, I took a picture and posted it to Facebook.

The next day, Skyping with my mother, she told me that the picture had shaken her. I braced.

“It looks like about fifty people were there out of a city of 15 million. Why can't these people find something better to do, instead of throwing dirt on their history?”

I said I didn't think anyone wanted to portray the Soviet Union as entirely bad. They were just remembering a side that they didn't want forgotten. That there had been plenty of stories of Soviet good, of Soviet glory, on TV. It was important to remember the people who had paid for it.

“Victims of communism. More like victims of nothing better to do. Who's going to read the names of all the victims of capitalist repression? Of every slave ship prisoner, every victim of American 'democracy promotion,' everyone who died under American-backed dictatorships? How much labour do the millions of people incarcerated in the States produce for free? Who's going to fund the memorial centre for victims of capitalist repression? I'll tell you. No one. It's bad for business. So why does pouring shit over the Soviet Union always get all the Facebook likes?”

“But isn't forgetting the dark side of Soviet rule just a way to be able to sell more Soviet rule?”

“No one's buying Soviet rule.”

She paused.

“You,” she finally said, “are falling into the same exact stupid trap I fell into back then, when I was your age. We let people make us believe that the West was better than us. That we had nothing worth keeping. We were too stupid to know otherwise and we let it be broken.”

I wanted to find something for us to agree on.

“It would take a long time to read the names of the victims of capitalism. A long time. I'd help read those names,” I said lamely.

“Yeah? So why don't you write a story about that?”

Why didn't I?

9.

Stalin is no longer a historical figure. He is an insurrection. He is what happens when words lose meaning, when my cousin mutters “American bullshit” after a woman hands him a flyer on the Red Square that says “human rights” on the cover, before he rips it to shreds. Stalin is simple because he is a lifeless statue, an object that people can imbue it with whatever meaning they wish. He is the truth when the truth becomes geopolitics. He is the “moral nihilism,” as Rachinsky puts it, “when people believe that what exists in politics is only what serves politicians' needs. The idea that people only act on material interests. And that all the conversations about human rights, international law, is all just a distraction in the game of geopolitics.”

Whenever I'm in Moscow, I walk through the Red Square. A few weeks before one cobblestoned visit in 2015, a group of young activists had staged a protest there, against what they saw as the return of the Soviet spirit into Russian politics. They doused holy water on the steps of Lenin's tomb, reciting incantations of “Be gone! Be gone!” like Orthodox priests, until security guards intervened and escorted them away.

That spring, at the metro outside the Red Square, I saw a man in a black parka browsing his phone behind a table of touristy kitsch. Soviet-era pins with space rockets on them, old military medals, T-shirts, magnets, and matryoshkas: with Putin's face on them, with Gorbachev's, with Stalin's. More recently—Donald Trump's.

I asked why he's selling the Stalin knick-knacks.

“People buy them,” he said, frowning. “So I sell them. What else am I going to do?”

The author of this piece wishes to remain anonymous.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Yeltsin cultural centre as a Gorbachev cultural centre. Hazlitt regrets the error.