For a novelist, nothing is quite as sustaining as a question that won’t let go. Some questions sustain a novel, others become lifetime projects. Alissa York once thought she’d study science to become a naturalist like David Attenborough, so it’s no surprise that the intersection of the human world with the natural one has become a career-long preoccupation for the Toronto writer. Who is hunter and who is hunted has never been far from her mind: in her first novel, Mercy, some of the most affecting passages belong to a butcher as he works. Her later novels continued to interrogate that point of contact via a young taxidermist, a federal wildlife officer, a veterinary technician and dispatches from the animal kingdom itself.

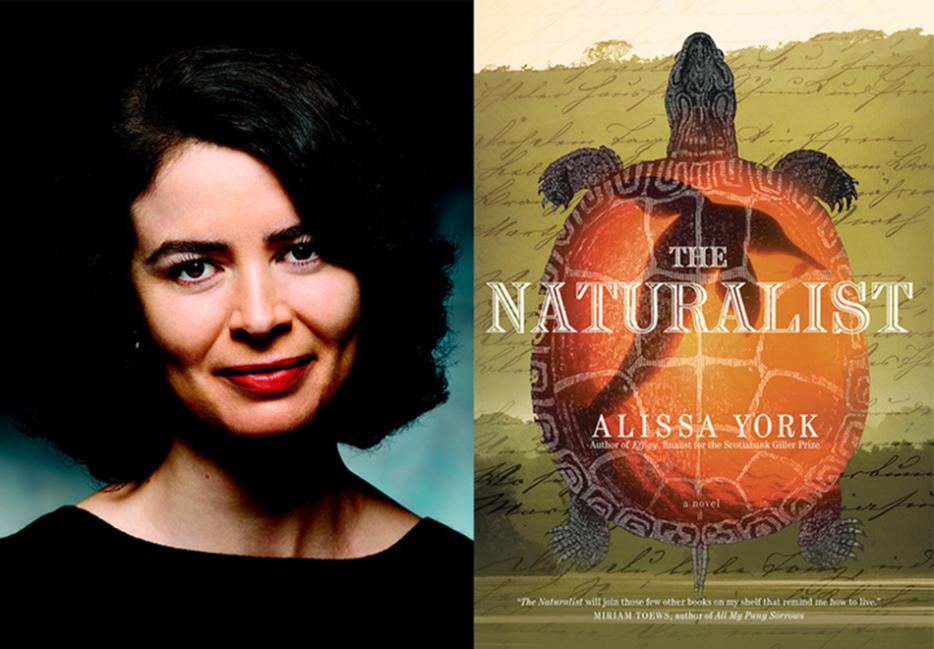

Full confession: I would read Alissa York’s grocery lists. I fell hard for her Giller-shortlisted second novel Effigy in 2007, and then I read everything else she’d written. Her latest, The Naturalist, is a remarkable novel, in many ways the one she’s been tacking toward through all the rest. Set in the Amazon, it teems with abundant flora and fauna. The humans in the novel—on a naturalist expedition without the naturalist—must be content with minor roles because the jungle is vast, unknowable, and deadly.

As in all of her novels, York probes the complex workings of the human heart with a sensitive and unflinching gaze. We met in Toronto to talk about the evolution of the naturalist, the mantle of legacy, somatic memory, and swimming with the piranhas in the Amazon River.

Christine Fischer Guy: The Naturalist teems with the textures and scents and sounds of the Amazon. You travelled there for your research, didn’t you?

Alissa York: I did. I’ve wanted to go there my whole life. I feel I came into the world wanting to go there. The research trip lasted ten days and I flew right into Manaus, Brazil, near the confluence of the Amazon and the Negro rivers, a big industrial city in the middle of the jungle. I was there for one night and then I was on a little boat with a naturalist guide, the captain, his wife and kids (she was the cook), and a family from the south of France. We were together for a little over a week on this small boat and on canoe trips and hikes, mostly along the Rio Negro, where a large part of the novel is set.

The boat broke down a couple of times, and while the captain and his son were jumping in and out of the boat working on the propeller à la African Queen, we sat and stared into the jungle and at the river. I did an awful lot of imagining.

How did this novel begin?

I started with the idea that I was going to write a novel set in the Amazon. As soon as I started to read the nineteenth-century naturalist accounts of the region, Alfred Russel Wallace, Henry Walter Bates, Baron Von Humboldt, William Edwards, and a few others, I had the very intense signal. That’s how I do a lot of writing—following the intensity of signals, or the intensity of the buzz.

So when I started to read those naturalist accounts, I was overwhelmed by that sense of pure excitement. I’ve found, with everything I’ve written, that there’s a sense of size: it’s never felt like a short story if there’s a novel there. Thinking about that way of being in the world—being an outsider going into a space that complex—had that sense of size to it. I began to work with the idea of a similar kind of figure. These men were all very young. Humboldt was independently wealthy, as was Edwards, but Wallace and Bates were middle-class fellows who set off for the other side of the planet in 1848 and made their living by sending their specimens back to England and selling them to museums and collectors. So that kind of trip was developing.

At the same time an echo trip started to develop that was taking place over two decades later, and for that trip a different kind of naturalist began to evolve. That required space for someone different. That trip is the naturalist trip with the central naturalist removed by circumstance, which left space for a young woman.

Being a naturalist like David Attenborough seems a vastly different thing from being one in 1867. Walter sometimes sold snakeskins and other animal artifacts, less a protector or documenter than a collector. Can you tell me a bit about that evolution?

It’s easy for us to look back and think with horror about how many birds Audubon had to shoot so he could paint them. The feathers fade really quickly once the bird is dead. So for that flamingo we see on the page… We forget that there were no telephoto lenses to bring those feather patterns close. It was quite natural for early naturalists to kill things to look at them more closely. There were naturalists collecting things for their own collections, and there were naturalists who were funding their research by collecting for other people’s collections. If you were Humboldt or Edwards or Darwin, you didn’t have to worry about funding, but if you did have to worry about it, that was how you did it.

And they had a fundamentally different view. They went into these spaces like the Amazon, and even though there was so much to know, they had those kind of cultural blinders on. Here they were going amongst people whose knowledge of this place was so rich and complex, and yet they thought of them, at best, as children. They missed out on a great deal by taking that attitude, and they did a great deal of harm.

I came across the term “extractivism” recently in an interview with Leanne Simpson: going into a culture, and environment, and taking what you can use. They did that too. But then, who didn’t, in those days? That was how you explored.

When did it begin to change? With the advent of photography?

Yes, photography changed it a lot. Women coming into the field changed it hugely. Some famous examples would be Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey. I do imagine Rachel, the young naturalist-in-the-making [in the novel], as a fictional precursor [to these women], because circumstance allowed her to have the amount of freedom that she needed to follow those instincts.

To Jane Goodall, it just made sense to go into the chimp’s space and let it be as much as possible on their terms. It’s the difference between going in to take something out, and going in to sit and observe and take notes and be present. Plenty of male naturalists do that now, too, but early women naturalists had such a different approach.

Changing attitudes towards animals and ecosystems was part of it too. In the mid-nineteenth century, there were plenty of indigenous peoples who understood the inter-relatedness of all things in an ecosystem, but explorers and naturalists coming from other worlds didn’t understand. We think of the Amazon as a fragile place now, but to them, there was not a hint of the fragile about it. It was as huge and beautiful and teeming with life as you could possibly imagine. They wrote about lying in their hammock of an afternoon and plucking up a beetle, and it would be a discovery. They were utterly overwhelmed with life, and they didn’t think in terms of something that could be extinguished. No one ever thought that the enormous herds of buffalo in the United States might run out. Passenger pigeons used to black out the sky!

Despite his heritage as the son of a naturalist, Paul is ill-suited for the jungle and feels an imposter. He’s more at home studying zoology at Harvard. Should a naturalist be at home in the field as well as in the academy?

Yes, I think so. It’s funny you put it that way. I myself have a little bit of the imposter going on. As a fiction writer, you have tremendous interest in the book you’re working on, and if you’re a novelist who writes books that require a lot of research, the intensity of that desire for knowledge is there. Then you go on to the next book, and you’re obsessed with that. So I have my abiding interests, and the natural world and animals in particular have always been an abiding interest and they come up in everything I do. At the same time, I’m not a naturalist. I’m fascinated by naturalists, always have been, and I dreamt of being a naturalist as a teenager, but really what I want to do is write about a naturalist. Those are fundamentally different things. But I do think that naturalists do want to be out there and they possibly have less fear to begin with, or they end up having less fear.

Paul’s feeling thrust into this, that he’s had the mantle put on him. He’s honouring his sense of obligation, but he’s not his father.

No, he’s not his father, and part of my process of discovery in writing the novel was to figure out, as he does, what Paul was. I knew, very early on, what he was not.

Though he compelled the trip, Walter is absent from it in all but an epistolary way – the remaining characters are facets of him: an academic, a field documenter, a custodian. Together, they make up for what’s missing. Did you conceive of it that way?

No, but that’s a really interesting way to think about it. For me it was more that each of them gets something different from being in that place. For Iris, his widow, I was very interested in the idea of grief unfolding in the place where there’s the most life force on the planet. That tension. I was also thinking about an artist’s response to that space, because she’s an artist. That’s where her passion lies, in the act of making the sketches and paintings. Walter’s passion worked very well alongside hers, and is picked up much more by Rachel.

And Paul? So many of us struggle with this. How do you become an adult? Well, you become your parent. Or you really don’t. Paul and Walter have been very close, they have a great deal in common. Before Iris came along, they really were a unit of two in the world.

In the rain forest, there’s an incredible battle for sunlight and water and space, so the trees and the other plants are incredibly clever. A strangler fig puts down roots and surrounds the host tree, then grows up around it, takes over its space, and kills the tree inside, so it’s got all this space inside. I liked the idea of Walter as a host tree and these others growing and taking shape around him, in the space that’s left by his death. They all love him very much, but there’s more space for them to become themselves when he’s not there.

And his presence, via the diary he left behind, is a haunting for Paul. His father’s legacy isn’t the comfort it might be for him. Do legacy and loss go hand in hand?

Yes, that’s very well put. What Paul’s dealing with, with those journals, is filling in some blanks in his own life that are allowing him to imagine himself more fully. As we become full adults, we have to do that or we can’t fully be ourselves.

He also feels a lack in himself. His father had that real courage and was a sponge for that kind of knowledge. Reading, learning, observing, drawing, taking notes… all the time. Paul has a different kind of mind. He has a facility with other things. But until he moves away from his father’s legacy, and part of that is dealing with the loss, he can’t stop being not-his-father and be himself.

Paul describes the flora of the Amazon as “the life’s work of a mad giant,” and free of what Walter called the “preposterous conceits” about it and its creatures, comes to know his place in it in a profound way. The jungle isn’t idealized, made monstrous, or stripped of its agency. How naïve are Iris and Paul and Rachel, going into that journey?

I don’t think they have a clue of how much it’s going to change them and how much they’re going to go through. I don’t think I had a clue, as a writer. I knew it was going to be the biggest challenge that I’d had so far. Just coming to know enough to imagine that story was huge. They are quite naïve, and each of them has the burden of grief, Paul and Iris the most. Paul has this huge challenge of being under his father’s shadow to being out in the world as a man. Rachel has an incredibly exciting movement into her own power.

Was Walter just as naïve on his first trip, or was he prepared in some way they were not?

Walter had the right personality setup and the right mind for it. I really was taken, particularly with Bates and Wallace, by their assumption that they could do it at age 20. There’s something about being a certain kind of 20-year-old man in the world, particularly from certain cultures where there’s an assumption that you can do it. How far that could take you in life! The tremendous curiosity, the courage, the sense of entitlement. I don’t think they ever thought, Would it be right for me to go into that space and take those animals?

Stripped of their familiars, all three confront the true frontier: themselves. Do we need the wildest of places to reveal our true natures?

I don’t know that we need the wildest of places. I think we need to move beyond our comfort zones, whatever they might be. When we are surrounded by safety and the known, it’s just natural for us to be not our largest selves.

Apart from practical considerations (19th century women’s clothing in the jungle, for example), how challenging was it to write these characters so far outside of their ken?

Extremely challenging, the most challenging writing I’ve done so far. There are so many types of jungle, there are so many types of river, there are so many species. How do you bring that to life?

Taking them there gave the novel momentum. The river trip was core to the original conception, and it works a magic on all of them, that place, that time. It was just opening up. The year before, 1867, steam ships had just come. To get from the mouth of the Amazon to Manaus (then Parà), went from taking over a month to taking a week! So the trip that the three of them take in ‘67 is very different from the trip Walter took in 1844. It was still this “undiscovered country” in terms of what the outside world knew.

Halves, or incomplete wholes, is a motif you use throughout: Paul’s heritage, the diaries his father left behind. Neither is whole outside Brazil—and yet Paul approached the trip with some trepidation, the way we try to avoid looking at unsettling truths. Did he sense that the Amazon would force a confrontation with his heritage and his father’s legacy?

Yes. He’s from that place, but it’s very much an idea to him. Before they leave, there’s a reference to a sketched-in mural that Iris is working on, and it’s a kind of echo to the jungle that Paul carries inside himself. He has no conscious memory of the place. When I was three years old, my family moved back to Australia for a while, then moved back to Canada. So I have this imprint: certain archetypal Australian sounds, smells, are inside me. I’m very interested in somatic memory.

Paul is also dealing with being mixed race, in mid-19th-century Philadelphia, and it’s a big deal. He’s managed to do a lot, given what he has to deal with, but he is, outside of his own family, an outsider in the world. He’s very uncomfortable with looking at that more closely, and he’s going to be brought right up against it.

Several of the characters speak only Portuguese throughout, which deepens the sense of place for the reader. Was that always part of the plan?

It was just a logical thing that grew out of my reading, and decisions I made. Deolindo, the mate on the boat, speaks only Portuguese and Língua Geral (the common tongue that was standardized by the Jesuits throughout that region), whereas Da Silva, the captain, could also speak English. That allowed a real intimacy between Walter and Da Silva, so you start to think about what you can share with people that you have full language meeting of the minds.

Rachel spends a lot of time with Tuí, who is a Juri Indian. He speaks his own language, which nobody else there speaks, and Língua Geral, and she only speaks a certain amount of Portuguese. They end up spending a lot of time together because they have a lot of the naturalist grunt work, so they have to find another way of being together. That took a lot of working out, and it was a real joy, because it had me right up close with how people communicate with each other on all levels.

I’m curious how writing dialogue in another language affected the process for you, because I’ve done a little bit of it too. Did it feel like a constraint?

Yes. How would a native speaker speak, how would someone learning the language speak? How does Paul’s young cousin, who has been learning English from his mother, speak? What kinds of errors does she make? How is her English inflected by Portuguese? It’s a complex thing. I did my best and then I gave it to my friend, Ricardo Sternberg, who is both a poet and a professor of Brazilian and Portuguese literature. He was able to come in with that fine-tuning eye of a native speaker, because he’s Brazilian himself. Things like, Yes, that’s correct, but it would be more informal and said like this. It’s quite a gift to have a contribution from someone who has that knowledge.

As the ship’s artist, Iris is an observer, a cataloguer, a kind of human-animal mediator. Is a writer a naturalist for humans?

I think so. Both Iris and Rachel, and even Walter, have writerly temperaments at work, maybe different parts of it. Iris is prone to falling under the spell of certain inspirations and she’s very dedicated to detail work. Rachel has that incredible receptivity and power of observation and natural organization to her thought. As a writer you have to have a kind of courage to continue and to write whatever it is you need to write, go where you need to go.

Through all of your novels, you’ve been investigating animal-human relationships, specifically the idea of who is hunter and who is hunted. In this novel, there’s a real sense of humans being at the bottom, not the top, of the chain. Was that a by-product of the research trip, or the thing that compelled it?

It’s a by-product of the trip and of the research in general. When I was getting ready to go down there and had my list of things that I should bring, one of them was bathing suit and towel. I thought, are you kidding me? I’m not swimming in the Amazon River. Do you know what lives in there? But then I was there. The teenaged kids from the French family I was traveling with kept asking to swim. Finally the captain said, You can swim here. They asked if there were piranhas. He said, well, there are piranhas everywhere, but you don’t have to worry unless you’re bleeding openly. I thought, OK. Piranhas aren’t what captures my imagination anyway. There are bull sharks, thousands of miles inland, there are caiman, and the list goes on.

But. I was watching these guys frolicking in the water and I thought, I may never come to the Amazon again. I have to get in the water. I had to get past a big barrier of fear in myself, and it really was the knowledge that nature was huge and more powerful than I was. We have the weapons and the chemicals and the big brain that gets us into so much trouble, but there are these teeny tiny viruses, or great big crocodiles, that can take us out in an instant. It’s very important to remember. In one way we’re top predators, and in other ways, we’re just not. Top predators [in the animal world] are so beautiful.

Human predators don’t have the same purity of motive.

Not now they don’t. Cavemen, maybe. When you think about that word ‘predator’ as applied to humans, that’s enough to get you started on how impure it has become.

There’s a suggestion that Paul will write into the void left by his parents. Is this how a writer is made?

I think so. Writers are so full of questions. I think we are all full of questions, but maybe for writers, questions bother us more, won’t leave us alone.