During the opening credits of Jonathan Demme’s 1986 film Something Wild, the sun rises over a series of banal New York City scenes—the skyline, joggers, a man with a boombox. The scenes are charming, I suppose, by virtue of their being in New York, but more endearing because of the background music. It’s a song called “Loco de Amor” by David Byrne, featuring Celia Cruz, her rich, heavy voice like a bell over Byrne’s faux-Spanish accent. When he sings “my little wild thing,” he thickens the “L”s, lets them linger at the roof of his mouth. It’s an enunciation you’re familiar with if you live in Miami, like I do, where Spanish accents have funneled into colloquial English and given it its own peculiar inflections.

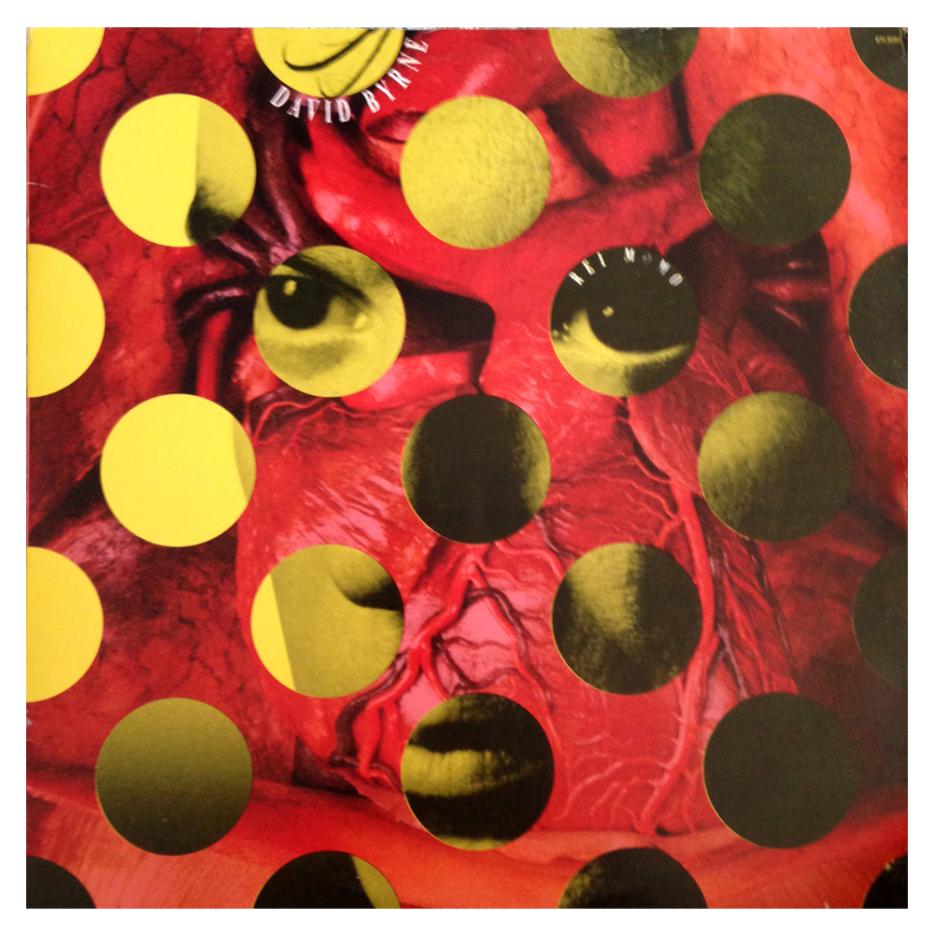

Something Wild has an incredible soundtrack: Laurie Anderson and John Cale are listed as composers, and there’s an iconic high school reunion scene in which The Feelies do a jangly, disinterested rendition of David Bowie’s “Fame.” But it was the Byrne/Cruz duet that led my parents to buy Byrne’s 1989 Rei Momo, where it appears with fourteen other Afro-Latin-inspired songs, performed alongside veritable musical geniuses: a bomba song with Willie Colón, a merengue with Johnny Pacheco, a pagode track with Arto Lindsay, a charanga with Milton Cardona. Cruz appears again on a song called “Make Believe Mambo,” the second track and my favorite on the album.

Rei Momo is Byrne’s first solo album post-Talking Heads, and it plays like an outburst of excessive energy, all synesthetic and dreamy lyrics (“I walk like a building/Never get wet”; “Talkin’ like a monster/Smellin’ like a baby/You got a head like a bowl of cherries now”; “Who is the lady with the sno-cone eyes?/Who has the candy with the soft insides?”). I was a baby in 1989, the year my parents moved us from Brooklyn to South Florida, and they played Rei Momo ad infinitum, listened to it in the car and on our new stereo and eventually live, when they went to see Byrne perform the album somewhere in Miami.

Sometimes I enter a state of magical realism in which Rei Momo is the soundtrack to my parents’ relationship: my biracial mom from Puerto Rico and my nerdy Jewish dad from Brooklyn, set to the tune of a white guy miming and mining the sounds of the Caribbean till it sounds distinctly David Byrne. (“But this is not a South American album… It's a David Byrne project through and through,” said Steve Hochman, in a 1989 review for the Los Angeles Times.) Byrne’s puckish sense of poetry, the blithe song structure so specific to him, unfolds awkwardly over rhythms that are much faster than his own voice—but it’s delightful, even sincere. It’s easy to daydream while listening to the album; to my count, the word “dream” or “dreaming” is sung on Rei Momo seventeen times.

My mother moved to the States in the early 1950s, when being mixed-race meant she worked extra hard to acclimate or sometimes disappear; eventually, she only spoke English. My sister, with whom I share a mother but whose father is also Puerto Rican, is brown; I’m the sort of white that has no business co-opting the signifiers of any other culture. Boricua, I felt, was not something I could own, and my obsession with my heritage—my need for it— bordered for a time on fetishization. I was jealous of my sister’s coloring, a motherly warmth that wouldn’t envelope me, passed down from the womb to just one of us. I insisted I was Puerto Rican when classmates’ insults became anti-Semitic and, when I was very young, let my dolls speak to each other in a kind of “Spanish,” a jibberish I’d invented myself.

My fake Spanish—and the cultural preoccupation that led to it—was not unlike Byrne’s fascination with Afro-Caribbean music, or with South America and the Caribbean in general. The fourth track on the Talking Heads album True Stories is called “Papa Legba,” an incantation to the Haitian loa of the same name. Byrne doesn’t have the lineage to properly summon up any deities, but he tries, fervently. In a New York Times review of the Rei Momo tour, Jon Pareles wrote, “Mr. Byrne's music has often been sparked by the friction between his own persona—stiff, earnest, Anglo-Saxon—and the abandon promised by African-derived styles from soul to funk to Nigerian juju.” I’m not comfortable with the idea that being Anglo-Saxon is akin to being “earnest,” nor the assumption of promised “abandon” by African music; it, too, reeks of fetishization. For what it’s worth, Byrne doesn’t seem to consider these problems; I want to believe there’s something innocent about Rei Momo, at least in its reverence for every explored genre and the familiarity found in each.

There is a tension on Rei Momo, though, and an abandon, too, and I feel both most deeply on “Make Believe Mambo”—a title I’d give to the chapter about Barbies speaking fake Spanish in the story of my life. Peppered with Spanglish toward its coda, the song is about a boy who constructs his persona based on television characters. “He’s got no personality,” Byrne sings, “it’s just a clever imitation/of the people on TV.” But the mambo is no admonishment. Byrne pities and maybe empathizes with him (consider the make-believe required of a white man to create Rei Momo): “Let the poor dream/livin’ make-believe.” Cruz steps in, picking up the string of English and following it till it’s Spanish: “In my mundo,” she sings, “todo el mundo.” I live in Miami, where Cruz, the Queen of Salsa, is a spiritual matriarch, and I take a strange pleasure in surprising my friends with “Loco de Amor” and “Make Believe Mambo.” “It’s David Byrne and Celia Cruz!” I announce. Though I’m sure I can be disproven, it seems as if Rei Momo exists in a vacuum—you’ve only heard of it if you’re of dorky, inter-ethnic parentage.

When I hear “Make Believe Mambo,” I feel an alacrity in my veins, something between relief and euphoria, like Byrne and Cruz are singing to each part of my background, acknowledging what’s invisible and present. There’s a video of a 1989 performance of the song, with Margareth Menezes singing Cruz’s lines. She, Byrne, and the entire band are dressed in white, like Santeros, and Byrne’s dancing unabashedly, brazen as a child. When I was very young, I told my mother I couldn’t dance; she immediately snapped, “You’re Puerto Rican. Of course you can.” I can’t dance, but that’s not really the point, and maybe it doesn’t matter—if Byrne can do it, so can I. For a withdrawn, awkward, and mixed-race kid grappling with the absence of an entire language, there is no phrase more apt than “in my mundo,” and that world is made up of liminalities, of daydreams and dreaming.