It was a rare clip because it caught us for more than a day. “Spook’s Paparazzi Assault,” the title he later swore wasn’t his idea, didn’t go viral, it went cult. “Full L. Ron,” a late-night host said, in a joke that bombed because the tour-bus audience had too narrow a field of reference.

Spook didn’t have a book or a plan like Hubbard, but he had a concerted path of action. He understood celebrity in a primitive, sun-worshipping way, joining the rest of us in building a personal pantheon, but surpassing us by deciding to become its champion.

The video was shot on a helmet-mounted Go-Pro, and starts with three seconds of idling across the street from Lure. There’s a lineup. We scan it along with Spook. Three lineups, actually: one for proles, one for bottle-service, and one continually vanishing line for faces that get automatic entry, or argue about being barred for a few brash then faltering moments. The bike stops idling and the kickstand descends. Spook approaches the phalanx of paps from the back, as they lean into their lenses to feed on the star-spitting side door that’s about to open. Spook gets closer and the crowbar rises into frame. Some people turn off the video here, but most are either too curious, or they’ve read the capsule write-ups that the video hovers above on a thousand viral content spitting sites.

The door opens and two ex-football players carrying an extra hundred pounds of fat from the long offseason of retirement try to create a path, careful not to clench a fist or shove directly, swimming through the digital cameras and thin arms just as the red-haired star emerges, her body tiny except in the areas where it’s not allowed to be, her expression drunk and with, as a later enhancement of Spook’s footage and four corroborating paparazzi shots will show, a narrow crescent of blood around her right nostril.

That’s when the crowbar, previously an inert presence in the lower right corner of the frame, takes its first lick. Spook uses it to heft a camera right out of the hands of the pap just in front of him, who doesn’t have it strapped around his neck. The $1700.00 Canon releases from his hands a moment before it shatters on the pavement. The paps turn, and for a second they’re aligned with the two-linebackers, an honour-guard for the liquor-blunted starlet who still hasn’t noticed that anything unusual is happening. Then the carnage starts in earnest. When it's clear to the guards that Spook isn't coming for the star, theyhang back to watch, too.

Most versions of the video have music added over this part. Techno, hard rap, or death metal, but the action’s all the same: Spook’s precise, camera-shattering blows, the way he darts and wheels with that thin piece of metal to smash equipment without grazing a face or an eye. Eleven are taken out before he’s done, the photographers screaming as Spook runs back to the bike and kicks it into movement.

*

“Go for hands and mouths,” Red Hat says. “You’re always going to get damage if you go for the mouth, and the hands send a message. No more clicking. No touching. No nothing.”

There are six of us in the alley behind Sator’s Haven, a Greek fusion restaurant some second-stringer bought as a project to distract himself between shoot-‘em-up, throat-punching sequels.

“Thumbs are good too. You break a thumb, it ain’t ever really gonna heal right. You wanna make an impact.”

No one knows exactly what they’re going to do here. That’s part of the plan—no plan to speak of, not on paper. Just some need, something we all agreed on in advance.

“And hit nothing if you think you might damage their target. The last thing we want. This is an act of preservation. Any of you idiots been in a museum before?”

A few of us nod. I used to practically live in one, doing archival work the year before I dropped out of grad school, but that has no relevance here. No one exposes any identifying features, biographically or physically. Balaclavas, one raccoon mask and an allotment of wrenches, extendable batons and a single gold fire poker, spray-painted black. It kept catching the light.

*

Voices clamour out front with the occasional pop of a flash, but the asset is still inside, still hidden behind the thick blue and white curtains pulled tight across Sator’s windows.

“No more sneaking up like Spook from the street. That’s ruined now,” Red Hat says. He’s the one who organized this, or at least the one who made the first post in the thread. His hat says Working Girl in silver sparkles. A gift after one of her shows.

“We go through the inside.”

An hour before the arranged clash, Reggie sneaks into his cousin’s room and suffocates Spook, laying an enormous body-pillow over his face and sitting on it, holding the bony pool-ball shoulders tight and still, kicking heels into Spook’s stomach to force air out and panic in, quickening the death. For the part that’s my idea, he spray paints a red ball cap onto Spook’s naked chest, then goes one inelegant step farther by filling a red Yankees hat with chocolate syrup and pushing it on to the corpse’s head. Reggie waits a few minutes and then discovers the body, sending their camp into maximum rage.

I decide killing Red Hat would be too clumsy, more likely to break spirits than raise them, so we let him live. It’s not a big surprise when he weaves Spook’s death, which was immediately tweeted with pictures, into our warm-up speech.

The pictures are the greatest insult, of course. The final piece.

“I’m not saying I did it, and I’m saying that none of us should say we did it, because we don’t want to be set up like dominoes in court. But, well, the thing happened. And one of us happened it.”

Red Hat smiles humbly, scratches an eyebrow with his right thumb, absorbing credit for the act. While he’s talking, I’m texting from Raccoon’s old phone, sending out rumours fake and real about the venue of our battle, ensuring that there will be paps out to shoot the clash while Reggie and I take care of the hijack and accident.

Raccoon’s mom keeps texting, asking if he’s gonna come home.

*

We steal a car. Reggie’s good at this, and it goes quickly.

Reggie talks about growing up with Spook, following girls down to the beach in the summer and taping them as they take off their tops to lie down in the sand. Taping them on actual physical videotapes, now stored in a box somewhere in his Aunt’s house underneath five years of dust.

Reggie says Spook said they were like explorers, the two of them, like they were discovering new lands, new places unseen by human eyes. The drop of a thigh into the knee, the weight of a calf tapering down into the Achilles. Reggie wants to stress this was before the internet, that Spook never thought of women as people, that Spook was addicted to pornography and surveillance and violence before he found a way to unite and justify his needs. Reggie says some men deserve to die.

We go with my target. He doesn’t have much security, not any really, and he’s always eating sushi on Thursdays—this is what we learn from three minutes of searching his name. We know he drives a blue Subaru, we know he likes to wear a baseball hat and we know that pulling up beside him at a red light should not present a problem.

where u at

I ignore Red Hat’s texts. He’s got enough boys now, all of them scared and angry, that he leaves me alone after just one message.

“You ever think you’d do your hair like that?” Reggie says.

The target is climbing into his Subaru, a misplaced extra sliding into the passenger seat beside him, tossing her hair like he notices. There are no paps around tonight, they’re all waiting down by the strip for the two sides to clash—the story has been hijacked. Reggie wants to get it back on track and an accident can do that.

“You know, let it grow out, grow a beard.”

Neither of us is wearing masks. The police batons rattle between us in the cup holders as we pursue the target through the streets, waiting for an opportunity on the tighter, hillside roads ahead. We are in an orange Nissan. We are not subtle. None of this has ever been subtle. Subtle is not for the news, the internet, the glossies.

The road begins to bank up a hill and Reggie tells me to pull alongside the target. We’re not here to scare him, I remind myself. We’re here to make something new. The half-forgotten ones are the best, I imagine. The scramble for a few TV clips, the desperate scouring of filmographies, bit roles and brand promotions. The need to say something, anything about the spurts of life caught by a camera.

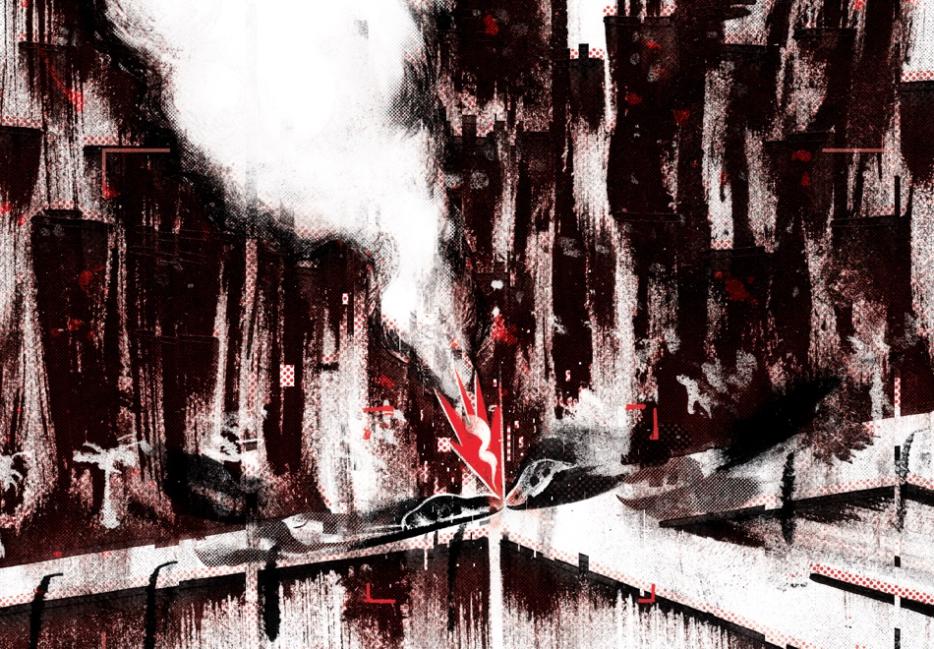

He doesn’t see us coming, so when the Nissan hits the Subaru, I’m surprised to see that his shocked face matches the one from that episode where he discovers his crush has actually been quite into him all along—it’s almost sweet, almost tender. Pushing forty and he still seems like a child. Is a child. They say from the moment you’re famous, you never grow up. I want to know if this applies to Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, maybe even Red Hat.

Metal on metal on metal as we slide into the guard rail, as the child’s face on the other side contorts from surprise into fear, into some sort of sneer, lips all purple, teeth racked against the glass, once, twice. My sternum whacks against the steering wheel and Reggie gargles something I can’t make out. Our target, fame a good ten years gone by now, has emerged half way through his windshield. No seatbelt.

Reggie is laughing. I can’t breathe.

There is no one here to take a picture. Not yet.

Reggie tells me this is just the start, a concussed delay in his voice. His eyes are glazed with blood and his teeth shine bright in someone else’s headlights.

*

We left a smashed camera in the stolen car. I’d picked it up on a long-ago mission, and the memory card was crammed with celeb shots. I’d spent an afternoon deleting the family and friends shots from it, hitting delete each time I saw a Hispanic face, losing a famous one here or there in my haste. It was enough, though. The artifact communicated what it had to: rogue paparazzi, likely drunk, had stolen a car and hounded an aging young star (they’d call him a star again in death, they were always generous when there was no threat of having to follow through on a favour) causing a fatal accident and fleeing the scene.

Our two rival gangs annihilated each other that night, breaking the gun rule and turning what could have been a memorable Outsiders clash into a crude exchange of bullets with a remarkable fatality rate. Even the cops got to join in on the fun.

Reggie joined the rest of them a few weeks later, but he handled his own bullet. He was wrong about his “just the beginning” stuff. Of course he was. The same law that landed in Paris after the princess ended up on the tunnel walls came down in Los Angeles and New York. The cameras were pushed back. Distance, restriction. The paps couldn’t come in to feed like they used to. Raccoon’s mom still sends the occasional text.

Whenever I walk by a marquee face now, outside a restaurant or a club that I can’t afford to get into, I sting with a want for them to recognize me, impossible as that is. They’re the ones who should stop, and wonder, and suppress the urge to worship. They don’t know, though, they can’t, really. I’m the one who made them more like us again. I’m the one who blocked out the sun.