Was it the moon? Something was shining down on Rose. She could also hear a sharp, staccato sound—like dishes shattering or a broken toy falling down stairs. No, she realized, it was laughter, human female laughter. Someone out laughing in the moonlight.

On the tops of her feet, she felt a mild cool weight. That must mean I’m horizontal, she thought. Very good! If she was lying down, there was a strong possibility that she was asleep, and only dreaming.

So let’s get on with it, her thoughts continued, as if she were taking her seat in a darkened theatre just before the curtain rises.

Then came a dim but unsettling sensation, a kind of stirring and probing deep inside her. As if she were a bowl of batter in which bits of eggshell had dropped, and now someone was trying to fish them out with his fingers. Dark shapes abruptly eclipsed the moon, then slid away; maybe the shapes were fish swimming over her? She did feel both heavy and weightless, as if she were underwater.

The stirring went on, and then another feeling, more urgent and ruthless broke through the membrane of her consciousness: pain. It glittered and writhed, twisting through her like a corkscrew. Pain like a state of unbearable intelligence. If she were dreaming, Rose told herself, it was now time to wake up and take action, take steps against this noxiousness.

But she was a stone that could not rise.

Then the corkscrew withdrew. Rose became aware of a bubbling sound, silver hammers tumbling. A cascade of notes carried her along, like Ophelia, a twig on a current. After a while, she recognized what this dancing, bright articulation was—music. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, to be specific, Glenn Gould’s version. She knew every note, it was the soundtrack for her daily stretching routine. There was the faint sound of Gould autistically humming in the background, so she was not inventing this.

Where in the world was she, Rose wondered, that the moon was shining down on her while her guts felt like the keyboard of a piano being played by Glenn Gould?

“S’my favourite organ, the liver,” came a voice, a little slurred, with some sort of English accent. “Just hanging out there under the ribs, not a poncy showboat like the heart. And look at the size of it! You could make a bloody nice handbag out of this one.”

Laughter, alongside a more metallic clatter, like silverware tossed in a drawer.

“What a tough bugger, too,” the voice continued. “You can drink bourbon morning noon and night for years, til your eyes turn the colour of dog piss …then lay off for a week, and bingo, the liver’s ready to go again, fresh as a daisy.”

This time the laughter was masculine, turbulent, a dark and moist convulsion in the chest.

“But the brain, Christ, watch out for that one. Bump your head on the bathroom cabinet, and that tapioca’ll turn on you. The brain’s like some chicks—cheat on ‘em once, and you’ll be paying for it til you drop.”

Rose wanted to agree about the cheating part, but her lips refused to move.

“F’rinstance, and this is between us, ladies, I haven’t really been the same since I fell out of that fucking palm tree,” the voice said. “I’ll be in the OR tackin’ up a hernia or something, nothing fancy, and suddenly my mind’ll go blank, yknowwhammean? Like I’m looking down at someone else’s dinner.”

More moist rumblings, like swamp gas bubbling up from some primordial place. The laughter formed a staggered bass line to the silvery notes that carbonated the air.

“Some bloke from a newspaper once wrote that I keep a picture of my liver on the wall at Redlands,” said the voice. “S’not true, of course. S’bollocks as usual. But they did make a little video of my liver when I was in Switzerland, having my blood washed, so I took a peek at that. And the thing was bloody fuckin’ impressive, let me tell you.”

Again with the wet rattling cough.

“Sweetheart, my hands are tied up here, d’ya mind tipping that bottle to my lips? And help yourself too.”

“Maybe after lunch,” said the gentle voice.

Swallowing sounds, protracted.

“So, yeah…my liver was brown, a kind of nice dark chocolate brown, and it was the shape of… that big rock in Ah-stry-lia, what’s it called?” the voice asked. “The famous one, you know….oh damn this palm tree brain…”

There were feminine murmurs, inaudible to Rose.

“Ayer’s Rock, yes, thank you Cynthia, you are a clever one! Yeah, so my liver in this video looked like that big red fucker.”

The voice, like the music, began to sound familiar to Rose, but the name that went with it kept drifting away from her. Kevin? No. The voice aroused a certain feeling, though, a friendly feeling, as if she were on her way for a drink or two with a solid old chum who had just turned up out of the blue, someone fun from her past. But the pawing sensation in her guts continued, and fought against this warmer current.

The stirring became an irritable tugging.

“I keep forgetting how complicated it is in here,” said the voice. “It’s all higgledy-piggledy, like some sort of bloody casserole my mum would make.”

“There it is, in the lower quadrant,” said a woman. “See? You may need this.” A slapping sound was followed by a new and more terrible pain. Rose’s sense of herself shriveled, like an insect that had blundered into a flame.

“I’ve got you now, you little cunt! Get the fuck out!”

There was a tweezing sensation, then the pain ended abruptly. Rose’s shocked soul bloomed again, a paper flower in a glass of water.

“Oh it’s a biggy,” said the voice, sounding pleased, “but the margins look clean. Nothing spreading into the pelvic cavity that I can see.”

Rose heard a wet plunk. “Take it down to the lab for the biopsy, but bring it back later. I’ve got plans for it.” Again with the loamy chuckle. The female voices giggled.

“Doctor?” said the gentle voice beside him. “There’s still a bit left in the bottle…”

“Pass it here.”

Lengthy gulping sounds ensued.

“Y’know, some pe’le say i’z a bad idea, to drink while you’re performin’ surgery on other pe’le. But! I pers’nally don’t agree with that. I do NOT agree with that! Because, if I’m really in the groove, really sort of feelin’ it, y’knowwhammsayin, another bit of the Jack just puts me even more in the groove. Am I right, Cyn?”

“Shall I clean up the abdominal cavity for you?” said the gentle voice. “She’s bleeding quite a bit.”

I’m bleeding, Rose thought. Pay attention!

“Oh yeah, Christ, that’s not good, be my guest. Mop away!” Rose felt herself being massaged from the inside.

“One more clamp…that’s got it I think. Good call, ladies.”

A fit of coughing came and then subsided. “Y’know, the sight of blood still puts me off. Guts, bones, crazy shit that glistens, that I can take. But if I have to get a needle, some sort of tetanus thing when I fall and cut myself, I don’t even want to see the blood climb up the syringe. Which is pretty funny, right?”

The gentle voices murmured words that Rose couldn’t make out.

“Whoa, look at the hemoglobin levels, better top her up. Hand me that bag, Cyn. It’s O type, right? What the hell, A’s fine. Ahanh! Just kidding. Now where’s the portal…annnd in she goes.”

A warm surge came over Rose, as if she were a loaf of bread being baked. It felt sexual.

“That’ll get you back out on the dance floor.”

Rose was getting used to having someone else’s hands inside her. You just had to relax into it, like a hard yoga pose.

“Bet you a bottle of Macallan it’s benign, even though it’s an ugly looking sucker.”

“Doctor, do you want Heather to close for you…?”

“No, for chrissake, I can close up, you think I can’t close up? It’s like the intro to “Gimme Shelter,” I can do it in my fuckin’ sleep!”

Rose sensed nips, tiny nips. What was the name of that Frida Kahlo painting of herself wild-haired, bleeding in a hospital bed, the red spilling over the frame? “A few small nips.” They didn’t so much hurt as tingle. She was floating right under the surface now, but she didn’t want to wake up.

Then she recognized the voice and knew why she was horizontal. She was being operated on by a seventy-year-old rock star and there was a bottle of bourbon going round the OR.

Oddly enough she was okay with this.

*

“Hey sweetheart,” said the frayed voice, “how’re ya doin’?”

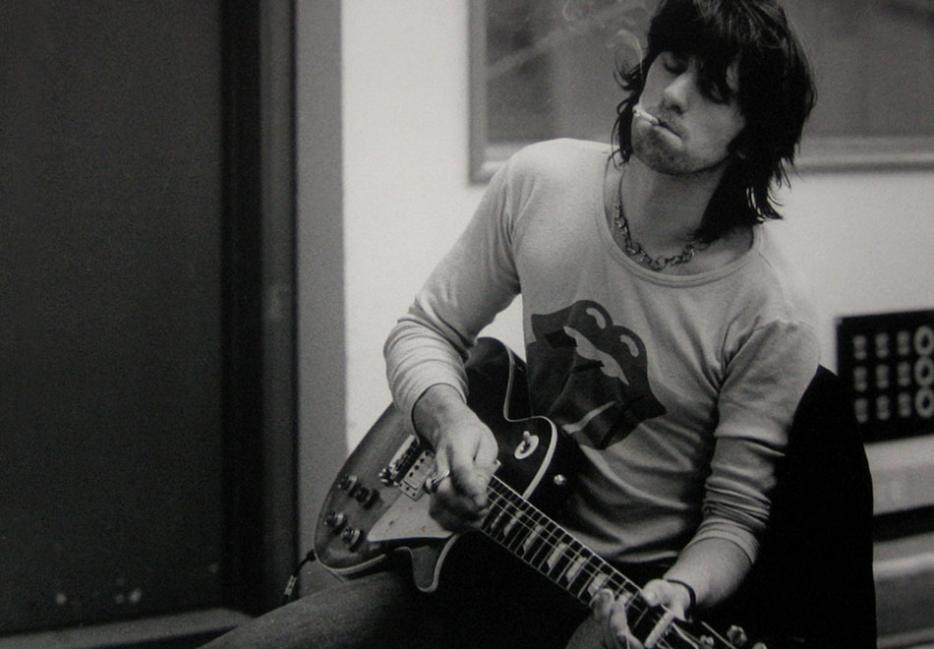

Rose opened her eyes. The moon was gone. She looked down; she was in a hospital gown, under stiff thin sheets, in a hospital bed. The figure sitting beside her wore green scrubs but his little cap had a skull pattern on it—skulls on skull, as it were. All up one hairy, muscular forearm he wore many-coloured beaded African bracelets. His hair was grey and pubic-kinky, escaping from the cap. His face was like something exhumed from deep in the earth but his brown eyes were warm and shining—surprisingly clear and healthy eyes.

“I feel like I’ve been run over by a garbage truck,” she said.

“Good, good, that’s what we like to hear. It means you’re alive and your body’s pissed off.”

Cautiously she shifted so she could look at him more directly.

Keith Richards, her surgeon.

“I’m sorry, I hope you don’t find it rude, but I have to ask…”

“Yeah, don’t worry, I’d be asking questions too.”

“Are you…like trained at this? I mean do you do this often?”

“Depends on whether the band’s rehearsing, but lately I’ve been operating once or twice a week—I did an open heart a couple weeks ago, which turned out pretty well. Not perfect, but the guy survived, more or less. Liver’s my specialty, though.”

“Where did you learn how to do this?”

“When I was in Switzerland. I met this cat who was into ‘expressive surgery,’ he called it. The jazz version, you know? He was a cardiologist but what he really wanted to do was play in a band.” Keith rolled his eyes.

“I get a lot of those. Anyway, I taught him some chords. He wasn’t bad actually, decent sense of time, and then he let me watch him operate.”

“Wow.”

“He told me, just do surgery the way you play guitar, and you won’t have a problem. It’s all in the hands, right? Which turned out to be true. I mean, you have to have good back-up in the OR, right? It’s like bein’ in a band that way. But if you kind of feel your way through the body, it usually works out.”

Rose’s mouth hurt at the corners, where her dry lips had cracked.

“Really? You improvise?”

“Well, I did practice. There was this junkie in the clinic when I was there, who was down to 80 lbs. and they let me operate on him.” Keith whistled.

“Oh man, I’ll never forget the look of that liver—it was like roadkill. But I kind of chipped away at it, cleaned it up the way you would your rose garden in the fall, and three hours later, the guy’s got a hepatic unit like a newborn baby’s. He wakes up feeling great, kicks his habit in a week, and now he’s this celebrity meditation guru.”

“Who? Durga Prasad?”

“Sorry, can’t name names. Anyway, when the operation was over, I was standing there with the scalpel thinking, this is my new instrument.”

“But doesn’t being a surgeon interfere with the whole music thing?”

“That’s kind of seasonal anyway, right? Bit like being a fisherman. I mean, Mick’s always got other stuff going on, he’s off getting his brows done or whatever. Buying new leggings. If I put all my eggs in that basket, I’d be fucked. This way, when we tour, I hang up the knife and don’t book any OR time. But if the band’s between gigs, I can do a little surgery and feel like I’m keeping my chops up, right? It’s all about the hands.”

“How does Mick feel? About you doing surgery on the side.”

“He thinks it’s a load of crap. He said he wouldn’t trust his Shih-tzu to me. Which is a crap thing to say, because operatin’ on animals is no piece of cake. I tried it once on Hooker, my black Lab, and never again!

An image of Frank, her aging Wheaton terrier, came into Rose’s thoughts and made her eyes tear up.

“But Mick doesn’t like me having a life of my own. He just wants me to get out there on stage, stay upright, and be more or less in tune.” His chest rumbled.

“I think he’s jealous. I think he’d like to do surgery himself.”

“Has he tried? I mean, do you guys all have special permits or something?

It was one thing for rock stars to snag the best table in a restaurant but she’d never heard of them getting backstage passes for hospitals.

“No, but he’d probably pick it up fast. Mick’s a detail guy, very neat. Good motor skills.” Keith made sewing gestures. “But he’s got a low fucking boredom threshold, and there’s a lot of drudgery involved in operating. Darning socks sort of thing. Mandrax is good for that part.”

A nurse came in, her stockings making a slithery sound, and gave Rose two white pills in a small paper cup. Just holding her head up to swallow them hurt her ribs.

“But I do like the liver,” Keith went on, sitting on the end of the bed and absentmindedly massaging Rose’s feet through the sheets. “I’ve operated on quite a few close friends, actually.”

“Anita, you mean? Did you do surgery on Anita Pallenberg?”

“No. Although we did fantasize about it.” He gave a warm chuckle.

“That bitch had the constitution of a Clydesdale. But I did, let’s see…Eric Clapton, and Nick Cave, and, funnily enough, Pavarotti—he had early-stage bile-duct cancer and I managed to nip that in the bud.”

“So if my…tumour turns out to be benign, should I worry about something worse, down the road?”

“Nah, your chances stay the same as anybody else. I think our bodies just like to grow stuff, like mushrooms in the forest—it’s their artistic side coming out. Cancer is just creativity run amok,” he said, fishing in my bedside drawer for any stray codeine pills.

Rose felt a wave of fatigue. She didn’t want to have a creative body. She wanted a dull one that behaved itself.

“I hope you don’t mind me saying, but I think you need to use more anesthesia when you operate,” Rose said. “I could even sort of feel you inside me when I was on the table.” The phrase made her blush. “And I could hear you kibbitzing with the nurses.”

“You’re joking! Oh that’s not good. I’ll speak to the anesthesiologist, or whatever you call him.” He gurgled. “You don’t want to be conscious for the sloppy bits.”

“It’s okay. It wasn’t torture, it was just weird. Especially since your voice sounded so familiar. I’m a big fan, by the way. I play Main Offender all the time.”

“Yeah. Good one, that.”

“So…it was a confusing, that’s all.”

“Look, sweetheart, I’ve had surgery too. It’s no picnic.”

“What happened”

“It was after I fell out of that fucking palm tree in Fiji. I hit my head, and then had an aneurysm. Nearly croaked. They flew me to the mainland, operated on my brain, and I was in a coma for weeks.”

“Oh my god.”

“World’s worst hangover, when I woke up from that. And I’ve had a few.”

“Did you think you were dying?

“I had the tunnel thing happening. The white light…train come in a station sort of thing.” He laughed. “Yeah, I was jamming with the big boys.”

“How did it feel?”

“Silly. I felt pretty arsed about falling out of a tree, and not a very tall one either. I thought about Patti, how I’d miss her, and the kids. Plus the band, of course. Even Mick. Basically I felt embarrassed to be dying.”

A slithery sound, as the nurse came back in. Her little name tag read “Shelley”.

“Dr. Richards, the lab reports are in. Do you want to take a look at them now?”

“Yeah, I’ll step outside with you.”

Rose reached out for his hand, and he took it in both of his.

“I won’t make you wait.”

They left the room and Rose lay there trying not to care too much about her life. She wished she’d said yes more often in the past, yes to risky things that might have taken her down different roads. But she had been brave, more than once. Marrying Eric. Having their daughter. The early years of writing with nothing else in mind but the right words. She looked back on her own innocence as if she was out walking a much-loved dog that had stopped far behind her to explore the woods, until she lost sight of the animal. But kept waiting, patiently, for its return.

Keith and Shelley came back into the room.

“I knew you were a lucky girl,” he said, his face crinkling. The nurse beamed too, as if they were a couple announcing a pregnancy.

“It’s negative?”

“Yes. Might as well be a giant freckle, really. Harmless.”

Rose wept a little.

“I was prepared for the worst,” she said, swabbing her cheeks with a tissue. “I always imagine the worst.”

“And now, we’re going to toast you.”

Another nurse brought in a trolley, with a silver shaker on it, an ice bucket, martini glasses, a jar of olives, a lemon, and a zester. And a small glass dish contained something grey and oyster-like: Rose’s tumour.

“Olive, lemon, or…

Keith pretended to slurp the tumour down, and they all laughed nervously.

“No takers? They say it’s exactly like a Malpeque, quite briny.”

Then he mixed some Bombay Sapphire gin with ice and made a noisy show of shaking it up. He poured it into three martini glasses and added curls of lemon zest.

Rose sat up, smoothing her dark hair behind her ears. She had an urge to cut it very short, and dye it patent-leather black, or fuchsia. There was the rest of her life to live, after all. The martini glass felt silvery cold in her hand.

Keith held up his drink and tipped his head forward like a monk.

“To your continued health.”

The nurse smiled, her eyes on Keith the whole time. It wouldn’t surprise me, Rose thought, if they had something going on.

--

Copyright Marni Jackson 2013