German cartoonist Anna Haifisch's career began in the world of fine arts. She studied printmaking in college, but through a string of trips to New York City post-graduation, she made the switch to focusing her efforts on indie comics, noticing the autonomy and playfulness the medium affords artists. In the past decade, she has made a name for herself through her unique visual style and touching storytelling. Her most notable contribution is the irreverent and endearing series, The Artist, which she originally published as a weekly strip on VICE and later compiled as a book for Breakdown Press. Many of the comic’s plot lines are all too familiar for anyone who’s experienced the lifestyle and insecurities of being a creative, and the book’s resonance with audiences eventually led to a nomination for an LA Times Book Prize in 2017.

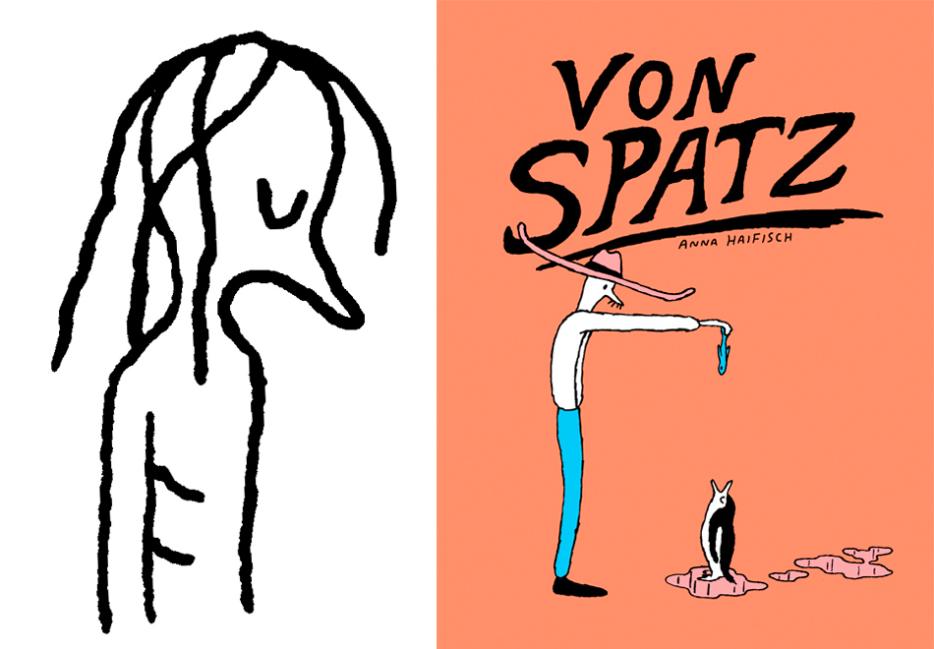

Haifisch has grappled with the minutiae and tribulations that come with being an artist throughout her body of work. One of her early books, Von Spatz, is being published, for the first time in English, this spring by Montreal-based Drawn & Quarterly. In it, Haifisch imagines a fictional rehabilitation center set in Southern California where 20th Century cartoonists Walt Disney, Tomi Ungerer, and Saul Steinberg have retreated after distressing experiences. Disney serves as the book's primary protagonist, and is checked in to the facility after a dramatic freakout at the company’s animation studio in Burbank. Despite the surreal set up, the book feels deeply personal and unexpectedly believable. Haifisch wrote Von Spatz with a loving pathos for her artistic heros at a very volatile point in their careers. It's a complex depiction of the fragility of artists.

Matthew James-Wilson: When did you first get into comics and what were some of the first comics that left an impression on you?

Anna Haifisch: When I was a child I read a ton of comics like Asterix, and other comics from France. I always loved reading comics, especially when I was sick as a kid. My parents would take out a lot of Asterix books from the library and I would just lay in bed, so glad to be reading them. It was like watching a series on Netflix, you know? That feeling of, “Oh, there are twenty more episodes?” but instead I had twenty more comic books.

But then I started studying art in 2004 and by then I was much more into fine art. I wanted to do woodcuts and ended up making super ugly art. I’m glad I did the bad stuff back then. I was really into printmaking and color separations and everything that came with it. It wasn’t until I moved to New York for a job that I came back to comics. I moved in with James Turek, who’s a comic artist from New York who now lives in Germany. So I started taking comics seriously as an artistic expression. Before that I was only doing zines and messing around with the medium. But that was in 2008 I think. Ever since then I’ve been hooked!

I feel like a lot of cartoonists I’ve talked to get into comics as kids, then fall out of comics as teens or young adults, and then get back into them once they’re older. How long were you living in New York and what work were you making there?

It was back in 2008. I was still studying at the art school in Germany, and this art school was really old fashioned. It was very German in a way, with all of the crafts, the print studios, the letter presses, and what not. Super cool but I felt kind of stuck there. But a lot of stuff was happening in New York at the time. I wrote a letter to Gary Panter and a letter to Kayrock Screen Printing on the back of two posters. Gary Panter actually answered me and was very friendly, but said “Oh, I don’t need anybody’s help right now,” which was totally fine. Then Kayrock Screen Printing—I just found that studio on Google—was like “Yeah, It’s sunny here, come over! We need somebody!” so I was just like, “Cool!” I had never been to the US before and it seemed so amazing. I had to fly out every three months and then come back, so I stayed from about 2008 to 2010 with several breaks.

I’ve noticed a lot of your comics make references to places in the US. Seeing the Morgan stop on the L train in Brooklyn really stood out to me when I first read The Artist.

The US has always been magnetic to me because of the culture. Whatever is coming out of the US, especially from New York, always seems amazing. I was born behind the iron curtain, and when the wall came down all of a sudden this stuff was available. It just seemed like the US was the way to go. Not becoming a citizen or anything, but going there and being a part of it felt great. When I was there everything looked so foreign to me. Whenever I took road trips with friends I’d love seeing the strip malls, the countryside, the barren lands where almost no one went. I loved the look of it and how simple it was to draw these landscapes. So it all kind of came naturally. It’s more than just a reference, it’s a really personal thing.

What comics did you start making after you visited the US? How did The Artist series come about?

The Artist came about because Nick Gazin sent me an email in 2015 and said “Hey, do you want to do a weekly comic for VICE?” I was shitting my pants because VICE is such a big company and it had to be weekly which was another big thing. So I was like, “Well, okay. Fuck…” I knew I had to draw and write about something I had a clue of because it had to go on and on weekly and I was scared I would run out of topics. The only thing that came to mind was being an artist, because there’s nothing else I’m really passionate about. I proposed like two episodes to Nick and he was like, “Umm yeah, if you could possibly do a comic about an artist, sure.” and I was like “Yeah, let’s try it!” Then it kind of just became a thing for me.

How often do you put your own experiences or life events into the work?

Nothing in specific is autobiographical. It’s not so much like, “I saw this and put it into the comic.” But because I’m friends with a lot of artists, and I’m an artist myself, there’s so much stuff to work from. When I have a beer with a friend, they’ll tell me this story about a gallerist, and it becomes a great story for an episode. Because I don’t want to do diary comics, I need a certain level of abstraction with my work. Of course, I’m exaggerating a lot. I hope it doesn’t come across as being ironic or anything.

Yeah, I feel like you’re really great at getting a personal tone across with your stories, regardless of however grounded in reality they are. You seem to be invested enough in the characters that they still feel genuine and honest.

Yeah! It’s very important to me that The Artist doesn’t come across as a comical figure. I feel for the characters. Of course he’s me in a way, and I don’t want to deliver him to the audience as a prototype or something. He’s definitely more than that. I love him!

When did Von Spatz originally get published in Germany, and what has happened since then that brought it to the attention of Drawn & Quarterly?

It’s actually my first proper comic book. I wrote and drew it in 2015 and it was published in Germany and France. Misma Èditions and Rotopol Press came together and shared the printing costs, and then it came out in the summer of 2015. It took a while to get to Drawn & Quarterly actually. I’m trying to remember how it got to them. In terms of The Artist, Breakdown Press was first in publishing it because they’re closer to my home since they’re in Great Britain. I think when Drawn & Quarterly came to me I said, “That book is gone, but I have this other book. Do you want to have a look at this?” I just sent over a PDF of it with the English translation in the comments. Then after that they picked it up.

I didn’t expect this to be happening. I was just like, “Ah, let’s see what happens,” and when they came back and said, “We actually want to do it!” my heart just skipped a beat while I was in front of the computer. I just started gasping and I hit the desk really hard with my hand out of pure joy and almost broke my finger. It was on my left hand, which is my drawing hand, so I was like “Fuck!” But really, it’s a big thing for me since it’s a big publishing house. I’ve always admired Drawn & Quarterly. The German publishing house Reprodukt picks up so many titles from them, so they’re very present here. I grew up with them! I read Julie Doucet in my teenage days.

How old were you when the Berlin Wall came down? How did that affect your exposure to other culture and media growing up?

I was super tiny—like three years old. But it took about another four years, when I was eight or nine, until the whole setting of the city looked okay. When I was a child everything looked grey and terrible. Buildings were just torn down because they were wet and falling apart. Plants would just be growing into them. This nasty old look of the city just disappeared. Also when I was a child, I grew up with Czech and Russian illustration, which was awesome stuff. That influenced me a ton as well. But then on the other side, all of the Disney stuff came in. McDonalds was a huge thing when I was a child. I was attracted as much as any child to American culture. It was in a very positive way. I don’t have any bad feelings about the consumerism that took me over. Even back in the day after the war, America was always a big thing here. My grandma always told me, “The American soldiers are the nicest.” It’s just this ongoing history through my family and through the country with America enlightening my warmest feeling, even though now the political situation is as awful as it could be.

This book in particular is an interesting examination of America. What attracted you to writing about Walt Disney and the other artists within it? What made you want to tell such a bleak story about someone who’s known for making such jovial work?

I think the first thing that drew me into the topic was a photograph I saw of the Disney Studios when they invited a deer over to draw for Bambi. They sat in a circle and drew the deer in a lovely atmosphere, and I just thought, What the hell? This is amazing! I was just hooked to that photograph and Walt Disney. He’s probably the most famous artist and visionary on the planet. Every kid grew up with his stuff. He’s not a fine artist necessarily, he clearly is a cartoonist, and he’s very close to what I do or what most comic artists do in general—drawing and having to bring characters to life.

The other thing was, I really wanted to draw California. When I drew the book, I had never been there. But the desert and the big cities—there’s so much ambivalence in that state. So just the pure joy of drawing it was a big plus. Then as another point, thinking about rehab as “the perfect place to be” and bringing those ideas together was always a dream of mine. When I started drawing the book, I always had the pictures of Lindsay Lohan with the e-cigarette and the ankle monitor in mind. Or the Betty Ford Clinic with all of the VIPs chilling there. Whatever they’re doing in there, nobody knows because it’s gated. But it always seemed like the most wonderful place.

I really loved the idea of using rehab as a foil for Disneyland, and comparing these two places that are sold as “the happiest place on earth” for different reasons.

Yeah! I think it was in Walt Disney’s opening speech at Disneyland that he called it “the happiest place on earth.” I’ve never been. But that idea sort of brings it back to the clinic.

One of my favorite pages from the whole book is the page where you see one of the characters looking out into this beautiful landscape with paints and an easel, and proceeding to draw a cartoon cat on the canvas. I think Sam Alden first showed me a print of it and he told me about how it spoke to him being someone who worked at Cartoon Network in Burbank.

Yeah, I sent that print to him because he told me about the bleakness of the studio world. He told me about how basic the office space is and he sent me a photo of it. I was amazed and shocked at the same time. This particular panel is just a mouse, alone in the desert, drawing his biggest fear. A cat. The mouse is Tomi Ungerer in Von Spatz.

Throughout all of your work, and especially in this book, there’s this constant relationship between being an artist and your mental health. What do you think is the correlation between the two?

That’s a tough question. It’s always a question of whether artists are mentally fragile or if making art makes you mentally fragile. It’s the same as “the hen or the egg” expression—you don’t know where it starts. I’m not sure if you’re born as an artist or not. I make this up in The Artist comics a lot. I think that being sensitive—maybe that’s a stupid word—but just being aware of your environment and getting hurt easily by it is probably a big plus for being an artist. You suck it up, and then channel it and make whatever work you want out of it.

Making art is so much about vulnerability. So many artists are either comfortable with being vulnerable or they experience being vulnerable so early on in life that they’re more fearless about opening themselves up to people.

Totally! Being an artist comes with the privilege of being a bit nutty. The outside world almost wants the artists to be like this. There’s nothing worse than being on a stage and not acting a bit disordered. The audience is almost disappointed. As an audience member you want to be surrounded by this weirdness. I’m trying to get into it more and more, but I don’t have the right formula yet for the relationship between the outside world and the artist’s world. They are quite different, but I don’t know in what ways. I’m not sure if you have to suffer to make a good piece of art or to write a good story—I’m not sure if that has to be the case necessarily. But I think you have to be empathetic to make art. If those feelings aren’t your own, you have to be able to feel other people’s emotions. It sounds a bit hippieish, but I think that’s important.

I think that sensitivity allows artists to process things that affect a society as a whole that are much farther reaching than just themselves. Then they’re able to be a voice or a vessel for that idea.

Yeah, that’s a perfect way to put it. That’s wonderful!

This book celebrates a lot of different artists. How do you see your inspirations filtering into the work that you make?

There are obvious hints in the book. The main characters in the book are Tomi Ungerer, Walt Disney, and Saul Steinberg. But I also have very hidden ones. Do you know Ed Ruscha? He had this piece where he made a stone and hid it somewhere—I think in California. This artificial stone is laying somewhere, but nobody can find it. So I put the stone in one of the panels. So there are a ton of little references. Mostly they’re just for myself, but I’m glad if people will see the obvious and not so obvious stuff. I’m not mad if nobody recognizes that one of the panels is a David Hockney piece. For me, it’s like paying a tribute to the artists I admire the most.

How has the internet affected your ability to reach an audience outside of your local one? You’ve really become an important figure in the international comic scene in the past few years.

Oh, that’s so sweet of you to say. I’ve always wanted to be part of the American comics culture somehow. Even if it was just taking part at festivals. For the first few years that was my main goal. Being there and looking at stuff and buying stuff—everything seemed so wild and reckless. I think my entry was VICE because that brought me to a wider audience. Every other thing I did was only known by a couple friends in the US and a couple of comic stores. But the constant work with Perfectly Acceptable Press, and VICE, and now major publishers, I’m so surprised that it’s actually happening. My heart is really beating because it’s a big thing for me. I never thought it would be possible at all.

What sense of community do you get from comics that you feel like is missing from the fine art world you were initially a part of?

The comics community is a lot more friendly because there's not as much money involved. I think that’s a very basic and pure fact of it. But still, in the past few months, I’ve thought Oh, this can also be a very toxic environment. There’s a lot of blaming each other and hitting hard on your fellow artists. The judgmental state is maybe even harsher now in the comics community than in fine art. In fine art, a lot of the not politically correct stuff would just slip through the cracks, because people react like “Whoa! This is art!” But with comics, it’s way more personal, and people assume that it’s a story about you a lot of the time. The comics community seems a bit more dangerous lately. But I’m happy to see it from the outside a bit and often from far away, because it’s terrifying.

What do you want people to take away from seeing the way that you depict artists in your work? Do you want to help people sympathize with the complexities of being an artist through the book?

Yeah, I hope so! One of my main goals is to convey a very lovely and gentle look at artists. Maybe they’re someone in your family or maybe your friend is an artist. I just hope that people can look at them in a very loving way with a lot of acceptance. Sometimes you just have to let them be.

The relationship between the artist and the outside world is so undetermined, but the immediate relationship with your family—if it’s your mom and dad, or your brothers and sisters, or your closest friends—they can say something and it can discourage you for half a year. The people whose opinion counts the most can say something about your line quality or the sloppy way you start your day, and then you’re discouraged for a long time. The books aren’t meant to be an educational thing, but I hope that somebody’s mom buys it and realizes that their child or maybe a weird cousin is actually just an artist. They might then look at them with different eyes.

I think the depiction of an artist has shifted a lot. Fifty years back, or even in the 1900s or the 1800s, the artist was always a mythical figure. It was like “Yeah, of course he has to hide for half a year in the studio. Eventually he emerges with a brilliant piece of work.” These days if you hide, you’re basically dead. In the fine art world, you’re totally done. That’s a dangerous path to choose. But every artist needs that time to be alone with their doubts and themselves basically. Nobody gives you that time anymore I think. I think that’s pretty new in the depiction of artists in general.