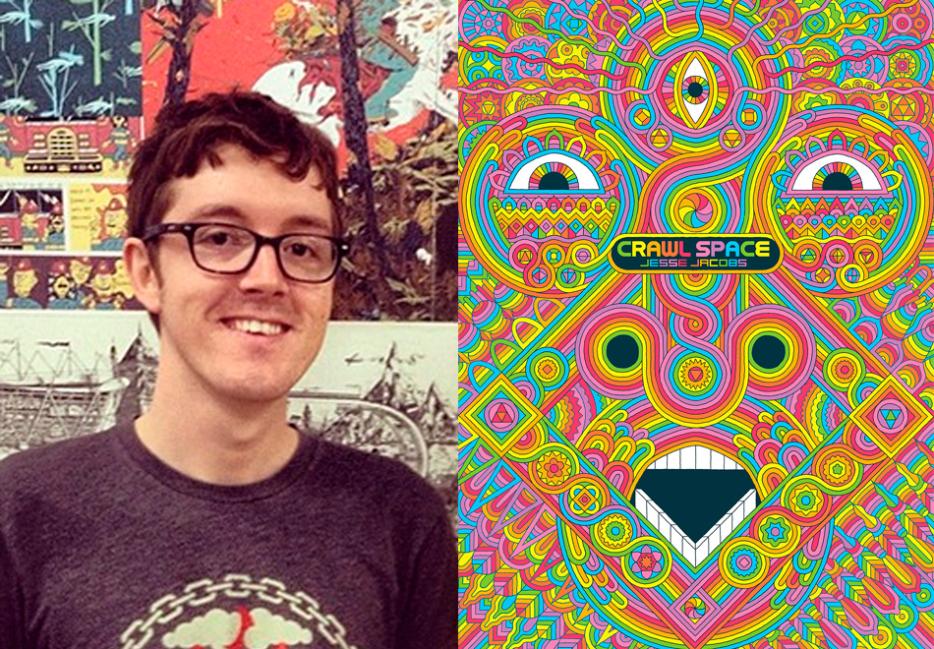

Jesse Jacobs is one of the many enigmatic Canadian cartoonists who have emerged from the blossoming comic scene surrounding Koyama Press. In the decade since launching the company, founder Annie Koyama has fostered an array of young artists, giving people like John Vermilyea, Jane Mai, Michael DeForge, and Ginette Lapalme their first mass exposure in the world of indie comics. After two well-received books with Koyama, By This Shall You Know Him and Safari Honeymoon, Jacobs returned this spring with Crawl Space, a 90-page short story that flexes the artist’s talent for design and new-age storytelling.

Jacobs’s work shifts between existential and comedic writing, tugging on his own personal experiences with love, nature, and existence. The atmosphere of Crawl Space is one that persists throughout his work, where humanity is at odds with forces outside its control and the landscapes often overshadow the characters themselves. This time around the otherworldly setting is an alternate dimension, easily accessed through an old washing machine, and the protagonists are a pair of unassuming high schoolers who curiously investigate the crawlspace. The teenagers navigate the psychedelic realm, interacting with the creatures that inhabit it, before realizing the impact the space is having on their bodies and perception of time. Throughout, Jacobs juxtaposes ideas of enlightenment with the sort of reckless but naive nature of young people, drawing on his own experience experimenting with drugs and spirituality during his youth.

I recently spoke to Jesse over the phone about what inspired the project and what he learned about himself while writing it. While I sat from a desk in New York and he sat outside his house near the Niagara Escarpment, we discussed nature, drugs, religion, and how to avoid making the same work twice.

*

Matthew James-Wilson: How did you start working on Crawl Space?

Jesse Jacobs: All of my longer comics I’ve put out with Koyama Press have started as small ideas that I intended to be short comics. But doing short comics is difficult, so they’d always just expand and I’d realize, Okay, this could be an 80-page book. It was even more so that way with Crawl Space, where I had the idea of these two beings in another realm, or however you want to put it, and emerging from it. Then I expanded on that. I did it fairly quickly, too—in about eight months with breaks here and there—but it was sort of done in a fervor.

What was on your mind when you started writing it?

It’s so hard to articulate ideas about spirituality and your place in the world, but that was definitely what I was drawing from. I’ve always been very interested in that. I mean, I don’t know how you could not be, being a human being. So many people, especially in my generation, are atheists or are almost allergic to any ideas of spirituality. I get that, because it is kind of drippy and embarrassing to talk about. I get sort of embarrassed just talking about it right now. But the book definitely came out of thinking about that and experiences that I’ve had in my life around spirituality. Crawl Space is much more sophomoric compared to a lot of the ideas I’m thinking about, but it was definitely coming from that place.

I was talking to [comic artist] Jesse Moynihan a couple months ago and he described such a similar quality or intention within his work.

I love his work—he’s very inspirational to me. I think all of my work has a bit of that dimension to it, even with the stuff that isn’t overtly about other worlds or spiritual realms. But it’s in there because that’s just sort of how I view the world.

There does seem to be a recurring theme of man in conflict with nature or the universe in your older work.

It’s a balance. I don’t really even feel like there’s a difference between man and nature—it feels more like one thing. Most of the time I feel that way, but then every once in a while, it’s jarring when something happens to you in the natural world that can really hurt or harm you. I’ve had experiences with ticks and things like that where you have to get checked out after getting bitten. There are little things like that that sort of disrupt your communion with nature. Safari Honeymoon definitely came from the idea that we are a part of nature, like everything else in the world, but sometimes bad things can still happen to you.

It’s funny living in the modern world—we feel so disconnected from it. It’s really easy to romanticize the natural world when you have the buffer of a house and electricity. When you don’t have those things it’s actually really terrifying.

As much as humans want to escape from the feeling that they’re not in control of something, there are still all of these forces in nature that remind us how little control we have.

It’s always so amazing when you see it happen in North America or in the west, when something like a big earthquake happens—it just seems different the way the media portrays it. If something like a big earthquake happens in a place with a depressed economy, it’s, “Oh, look what happened—that just happens there.” But then when it happens here in America, it’s, “Holy fuck … this can still happen? What do we do? Who is to blame?” It seems like after a flood or an earthquake we feel like we need to blame somebody. But it’s the same planet, so of course it’s going to happen to everybody.

There was a big snowstorm in Quebec this year, and all of these people were trapped on the highway for like eight hours—which would have been a terrible experience—but nobody died or anything. All hell broke loose though, and people were like, “We have to blame the government!” You just know it was people with the sort of libertarian-style worldview who were just like, “Where was the fucking government on this?!”

You’ve made most of your work while living in Southern Ontario. How do your surroundings or what you do day-to-day filter into the work you’re making?

I think a lot; the nature aspect of my work really comes out of that. I live in a place that is very beautiful—the Niagara Escarpment is nearby, and I have the lake in front of me, so it’s hard for that stuff not to seep into my work. I can’t actually draw plants and animals realistically, but the sentiments and the spirits of both come into it.

Are there specific moments or scenes in your life that worked their way into the book?

I think I was digesting a lot of experiences from my past. People read the book and they’re just like, “Oh, you must do drugs.” and for sure, I get that. Some of that definitely informed the book, especially experiences from when I was a younger person trying psychedelics and things like that for the first time. Those experiences, which have still stuck with me, came through. It wasn’t like I was trying to literally make a book about drug use or anything, but I can understand why people think that when they look at it.

It’s seems like we’re returning to an era where we can talk about psychedelics in the naive or curious way that the scientists who discovered them did before they were outlawed and demonized.

For sure. There was a lot of research going on that had so much potential in the ’60s, and they’re only now revisiting it, by using psychedelics for end-of-life treatments or to treat depression. I think it’s even funny how hyper-capitalism is accepting it now—like that whole micro-dosing thing that’s supposed to improve effectiveness or productivity in the workplace. It’s just like the way they take mindfulness and cherry-pick this one part of spiritual practice to improve productivity. You go to a corporate retreat and you’ll have some spiritual teacher teach you mindfulness for the weekend so that you can get along with your co-workers better or something.

Has spirituality always been a part of your life?

I grew up Catholic, but I was never fully confirmed. My dad grew up Catholic in Newfoundland, and was raised in a very Catholic family. When I was in about grade four or five he just had this realization and turned his back on it all. He became sort of allergic to religion in general, just from bad experiences with the Catholic church. So there was a void there growing up after that. I was too young to process that. Doing Hail Marys and the Lord’s Prayer—I didn’t really know what that was about. I just didn’t get it, or I didn’t have the vocabulary, so that sort of spirituality didn’t exist for me as a child. Then once I [turned] 18 or 19 I started to become more interested, and it’s grown from there.

I fall in and out of it too. Sometimes I’ll practice meditation regularly, and just be thinking about spiritual elements often. Then for a month or two, it just won’t even be a part of my life. I know I’m happier when it is a bigger part of my life or my thought process from day to day.

Are there other themes that you wanted to fit into this book?

I don’t think it was an intentional thing. I don’t approach a work thinking that I’m going to put certain themes in—they just sort of emerge naturally as I’m working on it. I think having young people populate the book seemed sort of natural, because it seemed like an innocent story. Even though this book has the longest page count of any of my books, it reads like a shorter work. Stuff has a lot more room to breathe, whereas my last two books, there’s a lot crammed in. This one is sort of spread out, which was intentional. But in terms of themes or what I’m trying to say, it just happens naturally. I remember this review someone wrote of a mini-comic I did, and he was talking about my work and that he really liked it, but he said, “Sometimes it leans too heavily on new-age sentiments and thinking that if we all get along everything is going to be okay.” I just sort of reacted like, Yeah, that’s kind of the point.

It feels like, in a lot of your work, the characters often take the backseat to the conflict or storyline. Do you have a hard time investing yourself in your characters when you’re so frequently putting them into danger?

Yeah, I never feel very connected to the characters. Maybe with Safari Honeymoon I felt the most connection. I think those characters were the most developed out of anything I’ve ever done. But I think one thing that Crawl Space and Safari Honeymoon have in common is that the environment itself is almost more of a character than the actual people. It’s like the space itself is the main star of the story, and then the things walking around in it are just sort of secondary. They’re almost just vessels used to explore the space.

How have you noticed your writing change since Safari Honeymoon?

Crawl Space was so different. Safari Honeymoon has more poetic language, and I toiled over the writing more in that book. That’s not to say one’s better than the other, because I’m working on another comic right now that’s closer to the writing style of Safari Honeymoon—it’s very intricate and plot-driven and there’s a lot of playing around with language in it, so it’s hard to say. I don’t think at this point in my life the writing is evolving as much as it is sort of circling around on itself.

What direction is your work going in at the moment, then?

I’m working on a [non-comics] project now, but I can’t say too much about it because it hasn’t been announced. It’s a lot like working on a comic, but with comics you’re so solitary and you make all of the decisions except for some minor editing and stuff. But with this project I have to work with a couple other people, and I’m just not accustomed to that.

I had another comic that I was working on when I started making Crawl Space, so I returned to that once I finished the book. I’m slowly picking at that. It’s going to be a longer comic. It probably won’t come out next year, because I’m working on this other project, but maybe 2019. I feel like it’s a new direction for me. I just did a two-page comic for the new issue of McSweeney’s, which is a big deal for me. So, I’m working on comics and just trying to not be repetitive in my work. It’s difficult for me because there are things in my brain that I’ll always think about.

Are there things you still want to push yourself to do in your work? Is there anything that’s still really challenging about comics for you?

I haven’t been working on comics for a couple months, so my goals are fuzzy. I don’t want to say I’m sick of doing comics, because I’m not—I really like it. But I think doing comics all of the time, for me, isn’t healthy. So it’s nice to be doing a project right now that’s outside of comics, but still flexes similar muscles. I think that helps me make better comics, too. I have some friends that only make comics all of the time, and I’ve had parts of my life where I do that, but it’s just too much. I have to get away for a little bit. I think taking space from it is the most important thing for me, to help me even be able to answer that question. I’m not even sure what I want to do with my future comics. I guess I just want to come up with interesting stories. Drawing is fine—I love drawing, and it comes much more easily to me than making stories, so I guess I just have to focus on better narratives.