I moved from India to the UK when I was a teenager—a sentence that begins numerous stories as old as the diaspora. What often follows: the wonder, the terror, the hall of trick mirrors unfolding wherever you go. This is the reflection I still see today: I’m 19, sitting on my campus-housing single bed with my new friends. We’ve come to adore each other very quickly, and as we chat, laugh, and sometimes disagree, my heart feels light and full. And then, a moment after I finish saying something, my favourite of these new friends widens her eyes and says in the softest, loveliest voice, “Sometimes when you speak, Richa, I feel really scared.”

There’s nothing that truly conveys the sinking shame of this moment; unless, of course, you’ve experienced it yourself. Ruby Hamad writes, “The younger cousin of the Angry Black Woman, the Angry Brown Woman is not critical: she is vitriolic . . . She is not assertive: she is scary. She is . . . permanently, well, angry—not because of anything that has been done to her . . . but simply because that is what she is.”

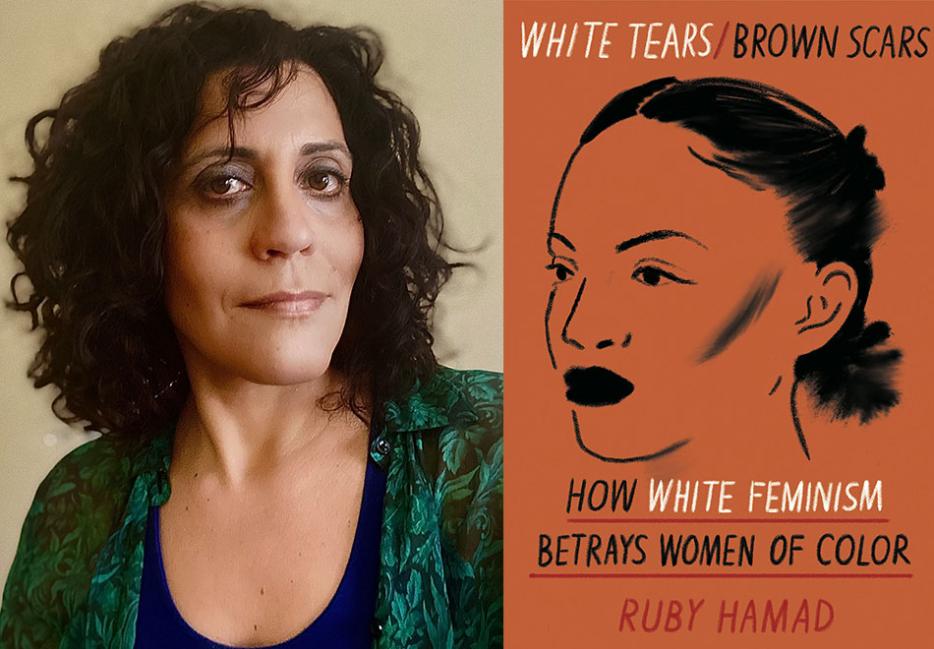

Hamad’s book White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color (Catapult) is an expansive uncovering of the ties between white supremacy and white feminism, and the resulting scars borne by generations of women of colour. With interviews, cultural criticism, and historical analysis, Hamad’s is a text in which women of colour will find much-needed solace, but also one that calls on white women to notice how they tearfully assert their own race to gain sympathy and support. The “damsel in distress”—like my soft-spoken British friend—is always white, and by virtue of her whiteness, is never scary or angry, and certainly never wrong. From BBQ Becky to every iteration of Karen, she is “just being honest”—or so she leads us to believe.

But, as Hamad writes, “For women of colour to be free of racism and for white women to be free of patriarchy, it is the damsel who must be damned.”

Richa Kaul Padte: Ruby, I don’t know how to even begin this interview, because I’ve underlined half your book! But maybe let’s start at its heart: white women’s weaponized tears. You write, “I couldn’t understand why and how I would end up apologizing to them when I knew they had . . . done me harm.” I double underlined and starred this, because it has happened to me so many times! I never gave it name or form, though, and always ended up feeling like I was to blame.

Ruby Hamad: Thank you Richa, that is so kind of you to say! This—brown and Black women writing to let me know they’ve experienced that same sensation you just described as they read the book—has by far been the most rewarding aspect of writing White Tears/Brown Scars.

You write, “Strategic White Womanhood makes personal what is political.” How does this reversal of the long-held feminist tenet through tears become an act of white power?

Ah, thank you for noting that! I was very deliberate in my choice of words there but I think you might the first interviewer to point it out? When I meant there is that Strategic White Womanhood—the name I give to the performative adoption of victim status—strips away political, social, and racial context, so that whatever the woman of colour says (my book focuses on the dynamic between white women and non-white women, though this also applies in other contexts), is reframed as a failing of her own personality. Rather than interpret her words as constructive criticism or as mere disagreement, Strategic White Womanhood positions her as engaging in bullying for her own individual gain. The white woman assumes the role of victim so that the woman of colour’s words are perceived as illegitimate personal attacks, as though she has some kind of vendetta. This, of course, buttresses white power because it negates the power discrepancy between white women and brown/Black women, and so reinforces the racial hierarchy that assigns innocence to white people and various degrees of guilt to everyone else.

That racism “is not so much embedded in the fabric of society as it is the fabric” has a lot to do with colonialism, where “White Womanhood . . . whitewashed the crimes of whiteness [and] functioned as the maternal arm of empire.” How did this play out, and what is the legacy it has left us with today?

Well, what I say in the book at several different points—and again this is something that surprised me as it seems to have been lost in much of the response to this book—is that my thesis in White Tears/Brown Scars is not only that white feminism exploits women of colour (though of course I do cover that terrain, too) but that there is a deliberate divide that colonizers created between European women and colonized women, and this gulf is the seed from which white supremacy was cultivated. White supremacy positions itself as “good,” “moral,” “innocent,” and “civilized.” All these qualities were said to be embodied in the white woman and to be entirely lacking in all other women, so much so that they were not regarded or treated as “women” at all. So, the legacy of White Womanhood is white supremacy. This is where so many of the attempts of white feminists to grapple with whiteness leave me cold. They still position whiteness as a problem of white males and patriarchy, where in fact, white supremacy has always been both paternalistic and maternalistic in its execution. Where white feminism comes into it is that, in order to understand why we have such a thing as “white feminism,” we have to understand that Western liberal feminism developed out of White Womanhood—itself a very narrow concept that was not so much about white women as people but white women as instruments of power—that was created in order to secure political, economic, and social (read: total) domination for whites in the colonies. So that is another legacy. White feminism is and always has been by its very nature an iteration of white supremacy. You can’t fix white feminism because it is not broken. It functions exactly as intended; you can only fight it until it is defeated.

Yes! The innocence and goodness ascribed to white women by imperialism was actively denied to colonized women, who were seen as “at once desirable and disgusting,” depending on what was convenient. You write, “This degradation served as both metaphor and rationale for the inevitable march of Western civilization.” How?

Well, metaphorically, colonized women were depicted as “easy,” and so conquering them was akin to conquering their lands. Their supposed “easiness” was then rationalized as the reason for their abuse at the hands of white colonizers. So, in the same way that the women were perceived as so promiscuous they were literally asking for it, the communities and cultures from which these women came were perceived as somehow willingly submitting to being colonized and subjugated. A culture that didn’t “respect” women in the exact way that European colonizers deluded themselves into believing they respected “their” women, was a culture that they believed did not deserve to exist.

You explore how white feminism uses the idea of a sisterhood to “appropriate our work to advance the myth of a better world run by women.” And it’s in the name of this same so-called sisterhood that we’re criticized for raising issues of racism in feminism, for wrecking sister solidarity. In this context, white women also “adopt a self serving ‘intersectional feminist’ identity, both as a shield . . . and a weapon.” This really stuck with me, and also made me wonder: should we aspire to something other than intersectionality—and if yes, what?

I appreciate this question so much. Again, you alone appear have picked up on an important undercurrent in my book, which is that I am increasingly dissatisfied with “intersectional feminism.” I want to be clear that this is not a problem of Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, but very much a problem of its execution once it became popular among white feminists. Intersectionality and “intersectional feminism,” in my mind, are not the same things. Even long before this book, I was noticing that “intersectional feminism” was only applied to those living in the West. So, we were seeing things like more brown, Black, disabled, queer, trans, and so on people in advertising campaigns for massive corporations like H&M, but there was little patience for engaging with anything but the most superficial critique of the business practices of Big Fashion, including of course the exploitation of the labour of women and girls in the Global South. I wrote several pieces on this in Australian media and gave some speeches on it too, but like a lot of things, the critique didn’t pick up here. That’s a whole other story, but Australia is particularly poor at having these discussions.

Another example that I do go into in the book is neo-imperialism and how there is just no room, it seems, for a genuinely critical mainstream feminist critique of Western intervention in the Middle East. What we do see is exaltation when barriers are broken in the military for women and other marginalized genders without much introspection on what the function of the military actually is in today’s world. It’s basically what I only half-jokingly call intersectional fascism—to be so mindful of everyone’s right in the West to engage in imperialism overseas.

“Whiteness was invisible. White people just were. They set the standard and we had to try and meet it.” I love that you reference non-white hair and noses to illustrate this (the two features that have plagued me the most!), but also the way you link this invisible standard of whiteness to colourism—“the yearning to distance oneself from Blackness in order to be included in whiteness.” And it’s true, there is such a deep-rooted belief in many (especially privileged) brown communities that we are “practically white.” Who pays the price for this bid that we make to “pass?”

Thank you! I want to clarify, as I have seen that line about the white standard referenced a fair bit, that I am paraphrasing Richard Dyer’s statement: “White people set the standard by which they are bound to succeed and others bound to fail.” But to answer your question, well, the people who suffer most acutely as a result of colourism and passing are dark-skinned Black people. The darker skinned you are, the more you will feel on a day-to-day basis the effects of a world that prizes whiteness above all else. We all, however, pay a price, some of us a larger one than others. I can speak to Arabs and the Levant region of the Middle East directly, as that is my heritage, and I will say here that I am immensely frustrated at how eagerly many Levantine Arabs embrace whiteness, as if they really see themselves as part of the white world because they are not as dark as some other races. It’s completely irrational because if the West genuinely regarded Arabs and the Middle East more generally to be “white,” they wouldn’t be invading and bombing it every two minutes. Palestinians would not be living under Israeli military occupation and Lebanon would not be permanently on the brink of total collapse, held hostage to sanctions. And, of course, we would not be blanketly demonized as savages, terrorists, and religious fanatics, as if these are intrinsic “Arab” characteristics. Whiteness is more than skin colour. It is a political status. You are not white merely because you see yourself as white—you become white when other white people decide to confer that status on you unconditionally, meaning you are privy to all the benefits that this status entails. It can’t be stressed enough: as fundamental as anti-Blackness is to racism, if we assume that being “white” is only about skin colour, then we will never understand it well enough to effectively challenge it. As I say in my book, “identity may be about how we see ourselves but race is about how others see us, regardless.” And please Arabs, read Orientalism (or at least an Orientalism explainer) before you try to claim whiteness!

Something I think about a lot is how colonialism mapped perfectly on to the existing caste system in South Asia—itself a logic of supremacy based on ethnic purity. For example, British women were known as memsahibs, who “constructed their own womanhood in opposition to the women they colonized” (a very Orientalist move). But today, it’s Indian upper caste women who are called memsahibs, so much so that until I read your book, I didn’t know the word’s origins! And I wonder, is this perfect marriage of imperialism and Brahminical (upper caste) supremacy one of the reasons you don’t explore South Asia much in your book? Because personally, I can’t imagine how we can even begin to address white supremacy until we dismantle our own terrible caste system.

I did not know that this is the current usage of the word “memsahib!” How fascinating. The reason I don’t explore South Asia as much as Australia, the US, and Rhodesia is because my main focus was Western nation-states that began as settler-colonies. But yes, India, like many Arab states, has to deal with its own internal system of oppression as well as tackling white supremacy. I cite the work of Neha Mishra, who argues that the caste system, although already in place before colonization, was not one based on skin colour, but that whiteness made it this way over time. I think that indicates how deeply enmeshed they are. I think a similar thing applies to the Middle East, where hierarchies were historically based on religious denomination rather than ethnicity. I think religion continues to be the dominant form of oppression in the Middle East, but over time this has expanded to incorporate race as part of its rationale.