During the year Anna Badkhen spent living with a family of nomadic cowboys in West Africa she met a young Malian woman who showed her a prized souvenir: a small aluminum ring with the name of a Swedish museum and a number etched into it. The ring had been clamped around the leg of a large white bird with a big beak, the woman tells Badkhen. “We have birds, but we never put rings on our birds,” the woman’s uncle said. “Who does such a thing?”

“What happened to it?” Badkhen asked.

“We killed it and threw it on the grill.”

“Oh my God was it tasty!”

“I’d never tasted any meat so sweet in my life.”

Months later, Badkhen wrote to the museum in Stockholm and learned that the bird had been tagged as a nestling in a forested, land-locked province in south-central Sweden, 3300 miles away.

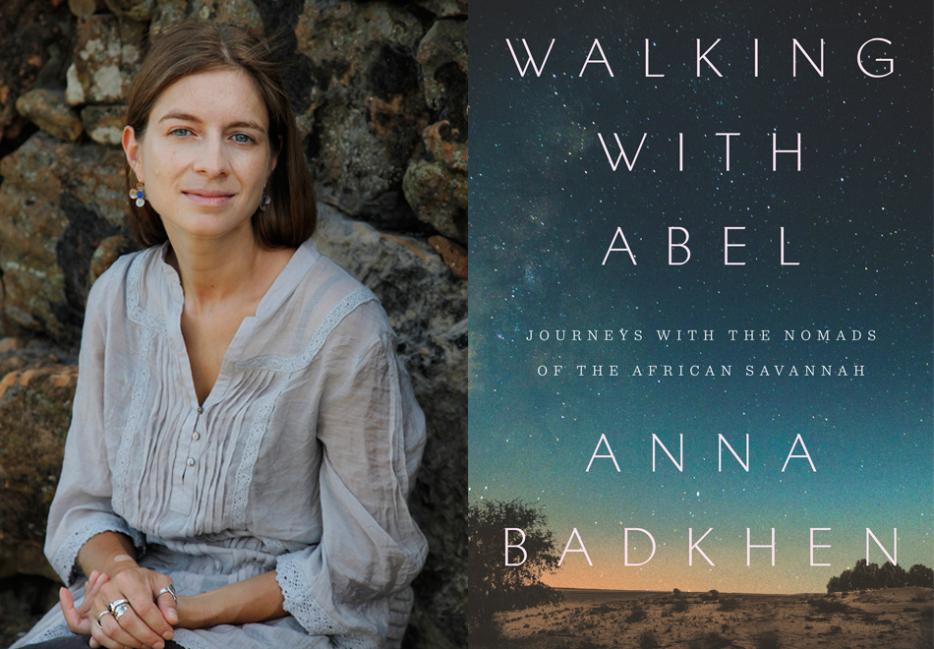

Stories of connections made across distances both geographic and temporal, and of the ways we understand and fail to understand each other (and the natural world), are some of the undercurrents of Walking with Abel: Journeys with the Nomads of the African Savannah, Badkhen’s account of her year on foot with a family of nomadic Fulani herders, which came out in paperback earlier this year.

“By the beginning of the twenty-first century, an estimated thirty to forty million nomads roved the world,” Badkhen writes. But climate change, urbanization, and other factors are putting pressure on the nomadic way of life; demographers predict that within a century, we’ll all be settled and living in cities. Walking with Abel is Badkhen’s attempt to distill what forms of knowledge, what ways of looking at the world, will be lost if humans become a stationary species.

Badkhen, who has reported from conflict zones in Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya, Somalia, and elsewhere, walks a tricky line; she’s allergic to sentiment and refuses to romanticize her hosts’ often difficult lives, but she’s alive to the beauty and wisdom of them, too. She lays out her intentions early on in Walking with Abel: “To enter such a culture. Not an imperiled life or a life enchanted but an altogether different method to life’s meaning, a divergent sense of the world. To tap into a slower knowledge that could come only from taking a very, very long walk with people who have been walking always.”

These days, Badkhen is working on her next book, about Senegalese fishermen, in a one-room cabin on a friend’s ranch. West Texas is very different from West Africa—the cows are so big that they’d astonish her Fulani friends—and yet the two places share a feeling of openness, and a broad expanse of horizon.

*

Rachel Monroe: What drew you to wanting to write about nomads? And why Fulani nomads in Mali in particular?

Anna Badkhen: All of my work focuses on inquiring about other ways of looking at the world. Offering different ways of seeing. My previous book, The World Is a Carpet, is set in a tiny village in the desert of northern Afghanistan, where my hosts were Turkomen shepherds who had abandoned their nomadic lifestyle. And what, I wondered, is the world when you live on the hoof?

The Fulani descend directly from Africa’s—and, possibly, the world’s—earliest cattle-herders. They have been walking alongside animals for at least 12,000 years. I thought: Walking for a living must give an altogether different method to life’s meaning.

Of course I had a few options. I could have joined the horse herders in Mongolia, or the reindeer herders in the Russian Far East, or Alaska. Like so many migrants before me, I was stopped by the cold. I dislike being cold very much. I’ve been cold enough. So, the Sahel.

You spent many years reporting from conflict zones. French warplanes and jihadists both make appearances in this book, but if anything it seems as though the real threat is from climate change. You write about how your host Oumarou “had not heard the planetary-scale metastory of the most recent global warming”—and yet, the Diakayatés have an intimate understanding of the impact of climate change. What are some of the effects it’s having on their transhumance?

The nomadic Fulani are entirely at the mercy of the weather. They may never have heard of climate change but they can describe with precision its symptoms: drier, hotter wind that blows for longer periods of time; desertification; shrinking pastures; dwindling waterholes; unpredictable rainy seasons; droughts that used to happen every decade or so and now whack the Sahel in rapid-fire succession.

Like most Malians—like most people in the Global South, indeed—the nomads cannot afford to stop divining the sky for rain. They have nothing to fall back on in case animals die. There is no system of social protection for nomadic Fulani in Mali—not even as limited or broken as the one in the United States. If their animals are thirsty or hungry, they die. If the animals die, the people die. It’s a very simple and terrible dependency. People who live in the Global North, though by far not all, are cushioned from it—for now.

The weather across the Sahel is becoming hotter, drier. Rainy seasons are unpredictable and unreliable. Meteorologistspredict that it will continue getting worse. The weather, along with globalization and mass media, will be one reason why the Fulani ultimately may be forced to settle.

In some ways, the subtext of this book is grief—for children who die and children who have died a long time ago; for relationships that have ended, for family members who are absent. How do the Fulani grieve? What impact did your own have while reporting and writing the book?

I hesitated to inject an acutely personal and temporary narrative of loss into a story about millennial transience. It was an anguished literary decision, one I did not make lightly. (My task is to tell the stories of others; I hate the spotlight.) But not being forthcoming about it felt more than run-of-the-mill withholding—it felt deceptive toward the reader, dishonest. Here is why:

The year I spent with the nomads I was missing someone very much, and my sadness contoured everything, created a frame of reference of its own. It clung to the savannah like wet silk. As my hosts migrated, in each of their footfalls I saw a separation. I saw them leave behind loved ones, lovers, their dead. I saw them shape their living within sequences of holding on and letting go, trying to accept the transience of everything—and to embrace man’s innate impotence to accept it. My narrative of their journey is an imperfect decoction of a world seen through my particular prism of loss.

My storyteller’s perception of the journey was so informed by grief that I am convinced my specimen year with the Fulani was irreversibly marred by it as well. Of course it is inevitable that our storytelling be deeply subjective always. Neuroscience explains that such inadequacy is predetermined and unavoidable. It is a function of anatomy. Something particular—this melancholy song of a milkmaid, that solitary cattle egret like an enormous lotus blossom descending—stirs the storyteller’s neurons to respond, rebates off the memories they store. Except these memories themselves are malleable, unreliable, even possibly untrue. Our brain may even create them on the fly, in the very moment of the encounter, when something indefinable in the unique and ephemeral soundboard of our cortex is strummed just so and resounds. Neuropsychologists call such memories, ominously, “false,” “ghosts,” “superposition catastrophes.”

In other words, what we elect to see and how we see it is irrevocably conditioned by our history, our longings, our joys, the way life appears to us in the specific moment of seeing, and our impulse to draw connections, identify patterns, establish syllogisms. The modest call it a coincidence and, virtuously, stop at that. Writers take or create context, then fit life into it. The result is a story.

You’ve described this book, as well as the project you’re working on now, as “magical non-fiction.” What do you mean by that, exactly? And why does that seem the right kind of style to tell these stories?

Ha—not a style, a genre rather, I think. It seems obvious to include magical thinking into narratives about places where magical thinking is the mundane, a part of reality, a necessity even. Magical realism originated in West Africa, and traveled to the Americas in the holds of slave ships—take a look at Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God. Same goes for magical nonfiction. Just read Wole Soyinka’s Aké, a memoir abrim with magic—and how can it not be? Sorcery, magic, genii are present in the everyday Sahel. Perhaps sorcery is the kind of covenant one needed to level with this land that can be so murderous, so brutal: to live and walk in the bush of ghosts. To withhold it from the narrative would be not merely dishonest: it would be strange. I am speaking in the present tense because my next book, Fisherman’s Blues, also with Riverhead Books, is set in Senegal and is, too, a book of magical non-fiction.

You’ve written about carpet weavers in Afghanistan and civilian life in Iraq. Do you see a through-line between your various works? How does this book relate to the rest of your work?

Absolutely. I explore the friction between beauty and violence, candor and disenfranchisement, the ancient and the modern—and our uncanny ability to adapt to all, and our connectedness throughout. The truest way to tell such stories, I find, is to live inside of them. The slowest form of slow journalism, if you will: being present, being awake, for a very long time. To write about the nomads, I walked alongside.

For most of my writing life I have written about, or from, conflict zones. It was a little intimidating in the beginning to commit to a long-term project not in a warzone. When I picked Mali—the Fulani live across the Sahel, in many countries—I knew that I would be herding cattle less than a hundred miles away from a war Malian, African Union and NATO troops are waging against a separatist movement-turned-Islamist jihad. An absurd comfort blanket if you wish. But, as you point out, despite its geographical proximity the war was barely a factor in the lives of my hosts, and so, it barely is a factor in my book. I learned, from writing this book, that the flashy and horrible drama of war is not what makes good storytelling. What makes good storytelling is attentiveness, respect, dedication, and hard work.

Walking with Abel also includes some wonderful little sketches of cows and hands and faces and more cows. When/how did you do these drawings? And why was it important to you to include drawings alongside the text?

I’m so pleased you like the sketches. A trifold explanation:

I love pictures in books. Who doesn’t? But photographs tend to communicate a sense of temporariness, whereas what I want my books to communicate is a sense of timelessness. Sketches are more out-of-time, less current, more ephemeral somehow. Hence, the sketches. Abel is the second book I illustrated, the first one was The World Is a Carpet.

A friend of mine—incidentally, a photographer; we worked together in Iraq in the beginning of the U.S.-led invasion—once remarked that smoking comes in very handy on such assignments: you are not just standing around waiting for something to happen, you are doing something. Sketching is like that to me: a great way of being busy and seemingly having a reason to be present without really participating. Also, sketching is meditative and absorbing. Like a breathing exercise. As is smoking, I suppose.

Lastly: When I was in my teens I wanted to be a book illustrator. Now I am a book illustrator.

Throughout the book, you reference Diogenes’s statement solvitar ambulando, it is solved by walking. Did your relationship to walking change after spending this year with the Diakayatés?

The nineteenth-century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard wrote once, in a letter: “every day I walk myself into a state of well-being and walk away from every illness; I have walked myself into my best thoughts, and I know of no thought so burdensome that one cannot walk away from it […] Thus if one just keeps on walking everything will be all right.” Diogenes of Sinope, who lived in Greece in the fourth century BC, promised that “it is solved by walking.” It is nice to mythologize walking—to bestow upon it incredible healing qualities—but of course it is not a panacea. You cannot walk out of grief. You cannot walk out of loss.

But you can definitely walk into beauty. You can walk with your heart open and let it be filled with new knowledge, new friendships, with new ways of looking at the world. I think the Fulani—who have been walking incessantly for at least 10,000 years, following their cows on transhumance—have a different way of looking at the world because they are always on the move, mobile. They are experiencing the world at the pace of three miles an hour. My book, in part, is about what that is like.