In the alternate-history 1950 of China Miéville’s newest novella, The Last Days of New Paris, Germany won the Second World War and Paris is an occupied city where members of the radical resistance thread their way through a city stalked not only by Nazis with bullwhips, but also bat-winged businessmen, giant, rolling eyeballs and wolf-tables with fangs and claws. These strange manifestations—“manifs,” the locals call them—are Surrealist art somehow mysteriously brought to life. Oh, and there are devils, too.

Miéville is known for writing weird fiction that, at its best, is both what he calls “a ripping yarn” and also an exploration of the subjects that fascinate him: linguistics, leftist politics, cephalopods, the trauma of living in a divided city. New Paris is on the lighter side for Miéville, playful and pulpy and visually delightful: “The chimneys of Paris are buffeted by ecstatic avian storm clouds. Bones inflated like airships.” I probably could’ve finished the novella in an afternoon if its extensive endnotes hadn’t kept sending me down various Wikipedia rabbit holes in search of more background about the unfamiliar (to me) Surrealist figures who populate New Paris, such as the magician-poet-painter Ithell Colquhoun and the avant-garde Resistance fighters of the Main à plume.

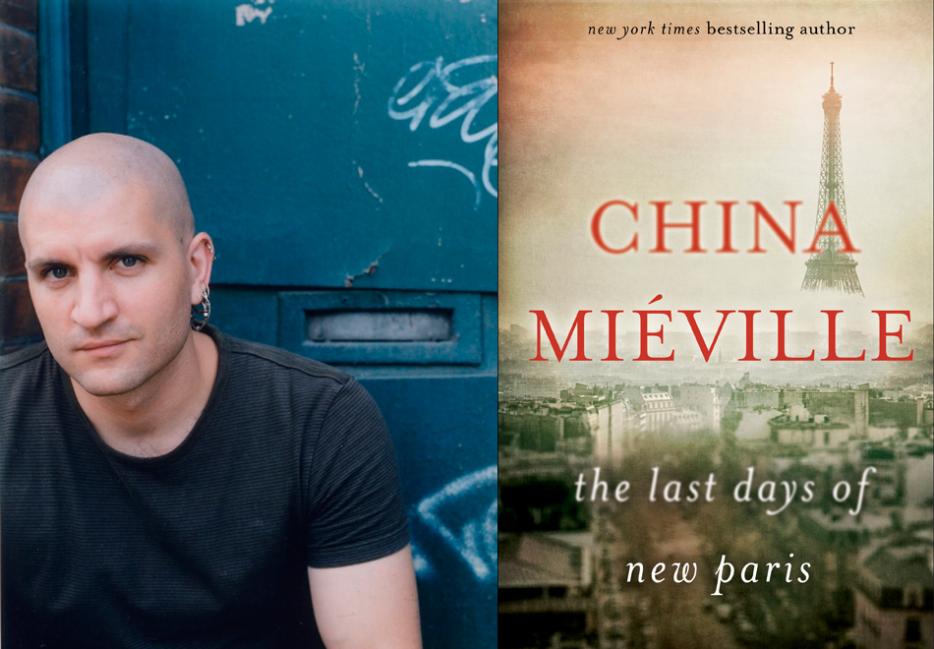

I talked with Miéville over Skype from his home in London. He speaks thoughtfully, in long, complete sentences. He has a tendency to make a statement and then immediately anticipate the argument he imagines other people might make against what he just said—or, sometimes, what he is about to say.

I have a poster of Dorothea Tanning’s 1944 painting Birthday on my living room wall. In it, a topless woman stands before a corridor of half-open doors; at her feet crouches a dark, winged creature—one which, incidentally, makes a brief appearance in New Paris. As Miéville spoke, I kept glancing up at the creature’s claws and wings and big sad eyes, this domestic demon of unclear meaning but clear significance.

*

Rachel Monroe: I was told that the idea for the novella started out as a video game.

China Miéville: Yes, it's a tie-in to a video game that doesn't exist yet, and may or may not ever exist. That's why it's a much more playful and lighter book than a lot of the other things I've done. I've long had this idea, for this setting for an open world, a sandbox game, and I was working on the world bible and the history [for it]. [The book started out as] a novella that was set within that world.

The shape of the narrative is an absolutely classic video game shape: a kind of looking around for things leading up towards boss battles. That's, if you like, the un-reconstructed element; then there's a reconstructed element. I'm not very good at video games, but I like playing them sometimes, and one of the things that frustrates me is the extent to which there's actually very little genuine randomization. There are the ways that you should play the game, even the ones that are designed to be highly customizable.

Within about two days of any role-playing game being released, there are sites online showing you how to optimize your character. I find that really sad. That's why I was interested in the kind of cross-fertilization with Surrealism—because Surrealism is so predicated on the automatic and the dreamlike. It’s no coincidence that one of the key characters in this is an exquisite corpse, which is, at its heart, something that you cannot build, something you cannot plan. It is intrinsically created in a kind of random interaction.

I liked the idea of [the story] being both an homage to the classic video game shape, but also something of an argument about the desirability of a truly randomized, anti-build mentality.

When did you first become interested in Surrealism?

When I was probably perhaps eleven or twelve, I saw Max Ernst's picture, “Europe After The Rain” in a gallery. It's enormous, and there was something about it that completely stopped up my breath. From then I became very interested in Ernst, but also the whole of the tradition.

Before that, as a very young child, I'd always gravitated towards both monsters and the monstrous, the dreamlike. What that meant was that a lot of the images that I was liking were in fact proto-Surrealist images.

There's a line fairly early on in the book where the manifs are described as provoking a sense of recognition even when they look very strange. What do you think is being recognized in those moments?

I think maybe this gets to the [distinction between] the specificity of chance and the automatic, as opposed to the merely random. Although there's clearly a lot of Surrealist techniques that do use genuinely random elements, “random” implies a sort of completely kooky arbitrariness. The idea of the automatic brings in some notion of, if you like, the non-random random. That's partly to do with the process of post-facto interpretation, and also to do with a sense of channeling.

Some of these images very quickly and very powerfully become heuristics, ways of thinking about things and relating to things, kind of embedded metaphors.

Some of these images have a semiotic fecundity that is very, very good to think with, and good to feel with. That's why some work is immediately very powerful, though it's difficult to express or to explain why. In a way that's the heart of what Surrealism, when it works—because some of it is crap—but when it works, that's what it does. Something that you can't possibly recognize, yet that you really do feel as if you recognize it.

Did you use any chance operations or other Surrealist techniques to create the book?

I did, but at quite an early stage, in some of the the maps, the nomenclature, the creation of the characters and so on. I suppose I have to cheerfully own the fact that by virtue of being a narrative shape and also being quite cheerfully part of a kind of pulp tradition, the novella is a clash of two different traditions in a way. It follows a certain set of protocols, which in a way is antithetical to the chance and the randomized. That oscillation between a kind of systematicity, a formal shape, and the eruption of chance is a productive tension that I've been interested in for quite a long time.

Many of the real-life figures who pop up in the book were completely unknown to me.

[The novella] is partly an attempt to perform an act of archaeology on certain very brilliant artists, writers and activists within that tradition, who I think have been neglected. This was an attempt to create a specifically radical and insurgent Surrealist canon, and to take that opportunity to honor some very powerful, and for me, very formative artists who I don't think necessarily get the respect they deserve.

Your endnotes point to a lot of the different historical figures and artworks that you’re referencing in New Paris—but I was wondering if there were any secret influences on the book.

There are certainly Easter eggs. Thinking of this as a video game, one would have all kinds of opportunities to stop the game to investigate sources. For the novella, many of the art pieces are explicated or referenced explicitly in the endnotes, but some of them are not. Some of them because I think that they're pieces of art that are already very well-known, and some of them because people always enjoy clocking things that aren't necessarily spelled out for them.

The Surrealists in the book aren’t just artists; they’re deeply engaged politically, too.

If the Surrealists, our protagonists here, are the goodies, that places them violently opposed to certain of the traditional Hollywood goodies: certainly the French government and the Americans. The cynicism about the supposed forces of liberty and freedom is inextricable from the aesthetic.

I think there's a great condescension towards [the Surrealists]—that these were a bunch of effete, silly artists who liked fucking about on the Left Bank, but who weren't serious political activists. There's no question that that's true of some of them, but I think it's a gross misrepresentation of what, to me, is the most inspiring of that current. These are people who are striving to make the best and the most powerful Surrealist art they can in a context of fascist occupation, against which they were fighting in ways that will see them sentenced to death. These are people who risked, and in some cases were subject to, death sentences. To them, it wasn't just a question of there being no contradiction. If you like, it came from the same pot. Their politics and their aesthetics were inextricable.

I do get quite angry about the idea that these were people playing around while the real politicos got on with the dangerous job. That's just, in many cases, grotesquely disrespectful. There's that beautiful line, which I quote [in the book], where [the Main à plume] confront the people who are saying, "Poetry is superfluous at this moment." Their response is, "The superfluous presumes the necessary." To them, we can only do our poetry because we are also doing the necessary, and the necessary means fighting back. That I find deeply inspiring.

How did the occult element become part of the world of the book?

Part of the pleasure of creating a world like this is its plenitude. In this moment in time you've got the very real obsession of certain wings of the Surrealists with the occult, and you've also got the very real obsession of certain wings of the Nazis with the occult. These are both completely real traditions. That overlap was aesthetically titillating.

I also didn't want it simply to be goody art versus baddy art, and that meant that there needed to be a third force. Once you add a third force, things begin to get much more messy, because otherwise, if you have your goody art versus baddy art, it starts to feel like this is a simplistic allegorical lesson, and I wasn't so interested in that. Given the complete obsession with deviltry that certain wings of the Nazis had, why not? It's fascinating, it's absurd. It has teeth, if you will. Taking that relatively well-worn idea, and cross-fertilizing it with the idea of the living art was a way I hoped to invigorate the world, so it had a certain messiness to it.

Once, having put demons in it, then the game becomes what can you do with demons that is not exactly the same thing everyone else has always done with demons? Can you introduce certain new elements to them, while still enjoying the fact that you're using the classic old image of a demon? How does it cross-fertilize with the art? What would it mean? How would they relate? That, ultimately, became part of the backstory, part of the highly absurd explication for how the world ended up taking the turn it does, as well as being part of the furniture of the city.

A lot of people I know have recently become more interested in Surrealism. I feel like people are suddenly always talking about Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, people like that. But maybe that’s just who I’ve been hanging out with. Does it seem at all to you like we’re having a Surrealist moment?

I've been very happy to see this upsurge of interest in [Leonora] Carrington in the last five to six years, although because I'm a bad person, I have that little flinch where something that you thought was your special thing that other people weren't into suddenly becomes trendy … but that's very ignoble, and one fights it.

I feel like Surrealism is one of those movements that is so ripe for appropriation, commercialization, banalization … sometimes with the active participation of the people involved as well, let's not be precious about it. Anything that anyone ever discovers that's aesthetically radical and interesting, they tend to think, "This time, it's unappropriateable. This time, it's going to keep its radical edge,” whether it's drum and bass or doom metal or whatever.

Surrealism was one of the earliest of those, and it's a kind of object lesson in the opposite: It could be commercialized and appropriated and, to my money, banalized almost from the get-go.

I suppose I see constant waves of interest [in Surrealism] since the ’20s, and there are constant appropriations and banalizations, and I can't tell whether it's an aspiration or a belief or something between the two, but my aspiration/belief, melancholically, is that there is also a surplus and a specificity to Surrealism that kind of appends to every moment of banalization. And yet there is still something.