A bearish shopper approaches Imran Siddiqui’s stall, carrying a ripped bag full of freshly cut meat, and asks for two books. Parked 500 metres away from a butcher shop in Karachi, Pakistan, his tables are full of volumes about cricket, children’s fiction, and sports magazines. “What kind of book do you want?” Siddiqui asks. The impatient man balances his ground beef and chicken legs in one hand, grabbing the first two books he sees in the other, wraps the pages around the raw meat, pays, and walks away.

Watching people treat the texts carelessly is difficult, but these are moral compromises he needs to make. Idealism is a luxury he can’t afford, with four children and an income of approximately 6,000 rupees a month. But his weekly chats with customers such as Sadia, a Master’s student studying English and closet poet who regularly reads her work to him, keep him going.

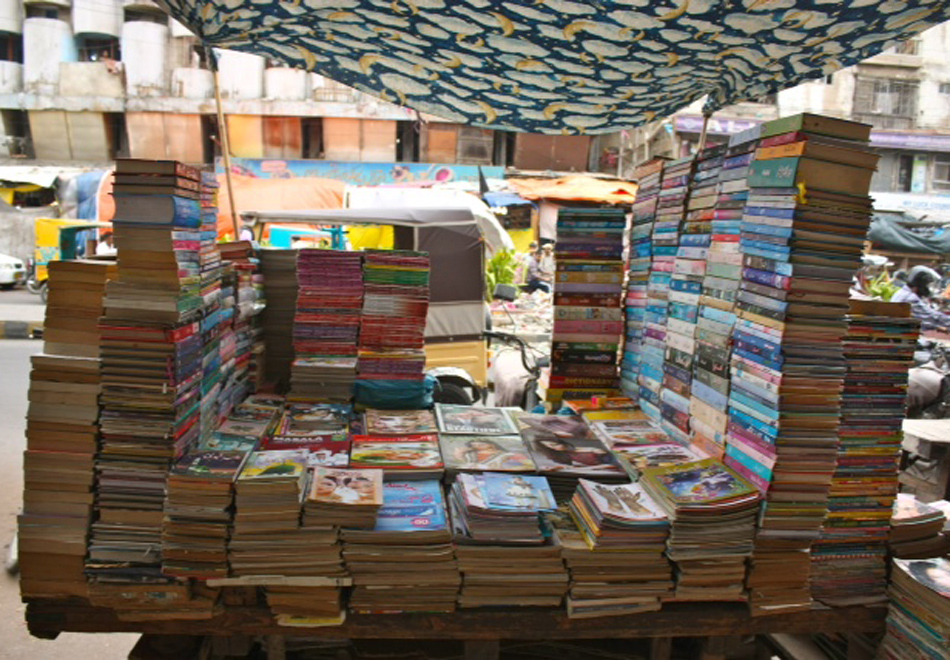

Although Siddiqui can’t read or write, years of serving Karachi book lovers has given him a respect for the written word. In a city where conventional book stores are few and far between, open-concept book stalls like Siddiqui’s can be found at beaches, outside hospitals, and in front of movie theatres and cafes. The owners are nomads-by-trade, moving frequently to unconventional areas. The majority of these book stalls are nameless; they take on the identity of the owner. Some of the books they sell are imported from Dubai or Singapore, shipped with costume jewelry and silks, while others are stolen from burnt-down or abandoned libraries; there’s a small group of men whose life’s work is to smuggle these texts and sell them to street vendors in a sort of literary black market. Like the origins of the books in which they traffic, they keep their identities secret.

The largest city in the country, with a population of over 23 million, Karachi has fewer than a dozen bookstores, most of which are located in isolated areas and are often poorly stocked. Ordering books online is not always reliable, and delivery can take a long time. Siddiqui and his peers provide many of the citizens of Karachi with their main source of reading material. The stalls themselves are mobile and easy to assemble, allowing their owners to move wherever business might be good, supporting themselves and their families in a country where poverty and unemployment burden many.

*

Mohammad Zayer pushes his portable bookshop to a parking area behind Meena Bazaar. He has become accustomed to the calluses that mark his palms and the dust that coats his feet. At the cramped women’s market, stalls are packed with handmade jewelry, piles of embroidered fabric, and traditional Pakistani home décor. Zayer, dressed in a once-white salwar kameez, has just returned from jumma prayers. It’s Friday, and the stores won’t open until the late afternoon when Karachi is at its hottest. He finds a large rock lying on the side of the road and places it underneath the partially broken left wheel of the book stall, which was damaged in a collision with a motorcycle. The weekend is near, and the market will soon be full of noisy shoppers. The 36-year-old man with thinning black hair pulls back the floral bed sheet that guards the books piled on the aging vessel, as he has done every day for the past 20 years.

Zayer has become an expert on choosing locations for his store. Shopping centres are the prime spots on Fridays, weekends, and in the evenings: people are out with their friends and families and in the mood to buy. On weekdays, he searches for shade by restaurants and office buildings, hoping to catch the eye of someone on lunch break. But he waits for holidays and the winter season, when he can go to his favourite place: by the water, where people eat spicy roasted corn and go for camel rides. He stands on the sidelines, inches away from the sand, enjoying the view.

A rusted steel weighing scale, traditionally used for fruits and vegetables, sits on the floor next to Zayer’s book stall. Magazines and newspapers all have a standard price, but books—most of them old and, in some cases, quite rare—are sold by tola, a South Asian unit of measurement that works out to less than a pound, for as little as one dollar. A several-hundred-year-old copy of The Royal History of England, with hand-painted borders and diagrams, can sell for less than a set of Harry Potter books. Early copies of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and collections of Shakespeare’s works are wedged between Pakistani gossip magazines. Zayer’s tea is always cold—he puts the cup down every few minutes to chat with passers-by or regular customers, some of whom are women carrying Louis Vuitton handbags, men driving Mercedes. They have been coming to him for years. He remembers the names of their children and their favourite authors. They greet him with a smile and sometimes bring treats for him to take home, an attempt to get what they need faster and in better condition.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Zayer can read and write. His father taught him at his own book stall when Zayer was six. Growing up in a low-income household, books were an escape on the nights when there was no dinner, when the roof leaked in the monsoon season, or when violence broke out in his neighbourhood. “It’s funny when I think about it,” he says. “The people who write these books have wild, beautiful imaginations, but I’m sure they never imagined that their work would be the life force of a man, like me, living in Karachi.”

*

Subhan, Zayer’s son, takes his place next to his father and a pile of old magazines, wearing his favourite army-patterned blue shirt. He is constantly at war with the flies that hover around the books. He hates the tiny, fast bugs, and swats at them persistently. The 12-year-old hopes to one day open a brick-and-mortar bookstore. “The love for reading is an addiction, like playing cricket or smoking cigarettes. Once you are hooked it is almost impossible to quit,” he says. A big fan of the Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib, he reads anything he can get his hands on and is always happy to suggest books to customers. Even though the youth literacy rate for boys in Pakistan is 79.1 percent, many boys—and even more girls—with the same social standing as Subhan do not have access to education. They are forced to start working at an early age, in some cases leaving their families behind in villages to find work in the city.

Zayer and his family live in a one-bedroom apartment with very little furniture, but lots of books. Besides the folding plastic table in the entrance room, where his five children take turns studying, are piles and piles of material for the store. Zayer married Nasreen, a woman with broad shoulders and green eyes, when they were 18. Their families had known each other for years and arranged their marriage when they were born. He taught her how to read, write and count, and today, they’re business partners—she keeps track of the inventory and helps him mend worn books. At night, his family browses the stacks carefully and chooses a book to fall asleep reading. A few blocks north, the book stall spends nights in safety on the lawn of a friend who sells bangles.

*

According to a UNICEF report from 2012, the total adult illiteracy rate in Pakistan is 54.9 percent. The population is divided between those who have a fleet of maids working for them, and those who live in overpopulated apartments, struggling to get enough to eat. Zayer is lucky to have been born into the book business. His friends and neighbours work at graveyards, are nighttime rat killers, or are terminally unemployed. He feels his work is a way to make taleem aam—knowledge and education—the norm, something he believes will alleviate the social struggle that surrounds him.

With every book Zayer sells, he imagines a new future for his country. He sees a ripple effect: the people who read the books he sells somehow pass along what they learn, whether they share the content or act on the values that these texts represent—hard work and creativity. “These small objects bring happiness, knowledge and companionship to our customers. These people are blessed with opportunities and money, they can do anything with their time,” Zayer says, “but they choose to spend it with this ink on paper.”

*

As the first drops of rain land on a copy of Oliver Twist, Zayer rushes to protect the books. He pulls a grey plastic sheet over them while Subhan props bamboo poles on the edges of the cart. After they tie those on, they throw another sheet over and create a tent around the easily spoiled material. Karachi’s weather has rotted the wood on Zayer’s stall in places, but he loves working under the exposed sky. “I don’t need to pay rent to work on the side of the road, to look at the clouds, to breathe in fresh air.”

He pauses to take a sip from his afternoon tea. “You know how there is a message behind every story? Well, I want the message behind my story to be that things are never what they seem,” he says. “Books appear to be frail and disposable, but they are sacred. You can burn the paper, but the stories live on. In the same way, a poor man or woman is not a burden on society, they are those who survive despite the odds—and when they don’t, they still represent those who tried.”