I first met Aanchal Malhotra at the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, where she was talking about the possibility that objects, the ones that survived the India-Pakistan partition in particular, have the ability to observe pain. For her, these objects, the only things that remained of home for many people, allowed them to remember. Malhotra showed a slideshow, featuring pictures of things that people had taken with them when one country was divided into two by a single line: jewellery passed down from generation to generation, a portrait of a Punjabi National poet, a rusted pair of scissors. As she spoke you could tell that her work was not only an attempt to understand a past, an event, it was an attempt to enlighten the future of that region. In a world constantly struggling between the need to remember and the need to forget, her work was inspired by a need to reclaim pieces of reality that exist beneath the surface.

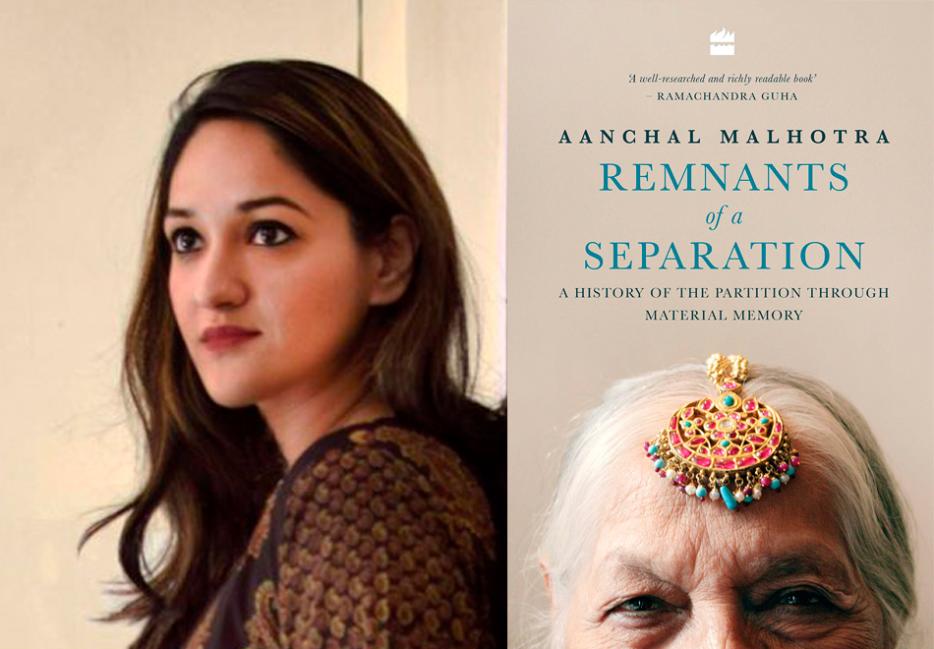

Aanchal was ending her day in Delhi and I was starting mine here in Toronto when we spoke about her bestselling book, Remnants of a Separation, A History of the Partition through Material Memory (HarperCollins India), her recently released digital repository, Museum of Material Memory, and what it means to be an oral historian. She slipped between English and Urdu, between her role as a storyteller and her role as a young person trying to unpack a past that has come to define a subcontinent. She sat in front of a bookshelf lined with books and a single lota (a round brass water-pot). For two people who were born on either side of the border, this conversation was as much about our own stories of migration, our own pasts, as it was about the ones she had collected.

Aeman Ansari: Tell me about where this project started. What does the process of bringing a visual history alive on paper look like?

Aanchal Malhotra: When I started this project, I was doing my MFA thesis. When you do a thesis in fine art you have to show it in a gallery. It started as a photographic project where I would take pictures of these objects and include small captions. My thesis was exhibited in a gallery that was 120 feet long and ten feet wide so that when you walked along side it, it seemed like you were walking alongside a border. One side of the gallery was glass and the other side was wall and when you were inside that very weird alley of the gallery it also had the feeling of being surveilled. Conceptually it goes back to how people felt walking along these lines during the Partition.

When I was putting up that show in Montreal at Concordia, I had this strange feeling that people needed to know more about the stories associated with these things. After I defended my thesis in 2015, I spent the next two years going through all of the interviews I had conducted about these objects and started writing about them. The book evolved out of the idea that these objects can be our portal to the Partition.

In writing a book that traces migration, you must have come face-to-face with a kind of migration of your own. How did you maneuver all of the borders and boundaries?

Often I was sitting in someone’s house and I couldn't understand a word because of the language barrier. One of my favourite chapters in the book is about a Bengali family in which I virtually understood nothing. They spoke for five minutes and the translator only translated for one minute. And I thought: surely I missed something.

The Partition happened to so many people, it is challenging to cross so many borders, not only physical borders, you are also treading on emotional borders. You are treading on borders of age, asking a generation their close-most thoughts. In the place between that side and this side there is stuff that has remained in this no man’s land. These conversations bring up that stuff and these conversations are the only things that will ever dissolve difference. I think these insignificant conversations, between these separate but connected places, will remove difference and distance. At least on a personal level, even though nothing may ever change on a political level, because you need the government to hate each other as much as you need them to work together. The other thing I realized when I was crossing all these lines is that I have the ability to bring about comfort and solace in someone. As a young person interested in old things, you must never take advantage of that.

Why did you create The Museum of Material Memory?

People got to know, from word of mouth, that I was writing the book. There are only ten Partition scholars in the whole world and they are all above the age of fifty. People started writing to me from everywhere and told me about the objects they had. I couldn't always go to these places so I thought people could write stories about their own objects. The purpose of what I’m doing is to empower people with their own histories. What is the one way that people from all over the world can contribute stories about objects that they are close to from a certain time in history, not only about Partition but even before or after it, objects of age? It’s a very minute thing in the larger scheme of things, but if we don't recall our own history, we will have regrets. So, I started a digital archive.

What was your introduction to the Partition?

School history text books, it was a very general introduction and I'm not embarrassed to say that I didn’t have much interest in it at the time. If you go to high school in India or Pakistan the history of Independence and Partition is obviously biased, but it’s also glazed over very quickly. It’s also rare for us to have learnt about oral history. When you grow up in the subcontinent you can very easily ignore the word Partition, less in Pakistan, but even then. So, when I came across these objects that my family had brought with them, I started repeatedly asking about them, but they didn't want to discuss it. They only wanted to talk about life before Partition and life after Partition. They didn't want to remember the time period during.

How does your own family history of migration affect your writing?

The first thing we have to understand is why they were so adamant on not sharing that experience. You will be empowered by your history only if you know the whole of it. Otherwise at some point it becomes fabrication. The work is as strong as reality allows it to be. So yes, my work was very affected by their stories, but more so by the perseverance of post-partition. My grandfather came with nothing and he built a book empire, we have owned a bookshop since 1953 in Delhi. He started with about 200 rupees for that shop. It wasn’t just my family’s story, it was the stories of that generation. When I started conducting these interviews I realized there were so many things that people of my generation need to hear. In India, we are a hugely intolerant generation, we are reactionary. We don't think, we say what’s on our mind because of the immediacy of social media. The things people from this generation were telling me about friendship, about courage, about values, I thought people needed to know.

You come from a family of booksellers, how has that experience informed your approach to storytelling?

I am of the firm belief that the more you read, the more you write. The irony is that my grandfather never read a book, he only read newspapers. Nobody forced anyone to read, but you have cultural legacy that you're a part of and you want to give to the literary society in some way, though I never thought that I would ever write anything, to be honest.

I started as an artist and I guess now I’m a writer, so when I read a book or even when I write it’s with the texture of creating something visual. It’s with the intention of making someone able to view a landscape in front of them. What is the purpose of art: the purpose of art is to make your viewer have something moved within them and I hope the purpose of literature is the same. When you make a piece of art you hope that someone will see it and remember it and feel like they are immersed in it. When you write a piece of fiction or nonfiction you hope that the reader is being transported to that landscape. I always look for that kind of writing that gives me the feeling of living inside something.

What are a few of your favourite books?

A Very Easy Death (Simone De Beauvoir), The Beauty of the Husband (Anne Carson), IQ84 (Murakami) and The Museum of Innocence (Orhan Pamuk).

There are a few Partition books as well: The Other Side of Silence and Borders and Boundaries, both talk about the experiences of women during the Partition. Yasmin Khan’s The Great Partition.

Writers often study the weight of the past and try to explore how the things that have happened to us change us, change the world around us. What inspired you to document this history of the past through objects?

Material anthropology is an academic study so people will mostly study it for archaeological purposes, or there are books about wars, and things that were found in the trenches. But that’s a very academic way to look at it. Considering that Partition is not dinner table conversation, how do you access it? What about people that have no tangible connection to it? What about people that have inherited only memories of it but have no way to actually find a way to get there? How do you connect to something that you've been disconnected to for so long? The youth of India and Pakistan are progressing really fast and not realizing the things that we are leaving behind. It becomes very difficult to access the past if we are not constantly involved in it and if it’s not constantly alive in our households through traditions and customs. These objects then become catalysts to enter the word Partition and also become a way to bridge the generational gap. The object becomes a catalyst removed from them, it is not about them anymore, it’s about this thing.

How did put together a piece of nonfiction that works to reconcile the division?

What I don’t like about Partition is that whenever you talk about it you talk about the violence, you talk about the hate. You can’t ignore that, but there are also instances of friendship, of courage, of sacrifice, of Muslims harbouring Hindus in their house, of a Sikh man adopting a child of another religion. I can’t say that everybody helped each other, of course not, but aren't these the narratives that we should be listening to? It is not about blaming anyone, because you can’t blame anyone, it wasn't the English, it wasn't the Muslims, it wasn't the Hindus, it wasn't the Sikhs; it was halaat, circumstance.

The narrative that a third-generation individual inherits from their ancestors is one of distance. You have the luxury of distance and education to view the event objectively, should you choose to view it like that. And even when you view something objectively, you cannot view it completely objectively because you have your biases and those biases are ingrained. What you can do is hope to portray a realistic narrative so that your subsequent generations can have something to think about.

This Muslim man that I talked to in Delhi, he told me that his father used to work for Viceroy house and he chose not to go to Pakistan. He said, “Hindus are born in India, they live here and when they die you cremate them and you submerge their ashes in the Ganga. Then their ashes go to International waters. A Muslim person is born in India, they live here and when they die, their body eventually decomposes and becomes the soil. It might be the land you are walking on right now. How can you say that that person does not belong on this land? They have become the soil.” Other people of my generation don't understand the repercussions of the reactionary measures they are taking against one religion or another. They need to hear these stories.

How is your work different from the work on Partition before it?

I’m using new age tools like digital media, and social media. It has the kind of reach that nothing else does. People are talking about objects from one part of the subcontinent to the other. A person from Asam can look at a plate and say, “how interesting, I have the same plate in my house.” A person from Karachi can say, “I have that same plate in my house.” The two people are talking over comments in my blog and not saying you are a Hindu, you are a Muslim, etc. None of this matters because they are just talking about that plate. How will you ever get to witness something so beautiful anywhere else?

You are a self-proclaimed oral historian. With oral history, you have to understand that memory is unreliable, and that memory deteriorates with time. How did you get past this fact?

You don’t. People think that oral history is not a viable source of information, unfortunately it remains the closest to authentic experience. But oral history cannot and must never be seen in isolation from academic history. They must always go together, I saw this in my own research. I cannot trust memory because memory will always change depending on your age, your experience, depending on what you’ve seen. It will change. In this case, another interesting thing happened, collective memory becomes personal memory very fast. When you have lived through a traumatic experience, even if you have not seen someone getting killed you will say, “yes I saw that because everyone saw it.” The only thing you can hope to do is supplement oral history with academic history. I did a lot of crosschecking, almost on every single point, it supplements fact with memory. I spent months with secondary sources, because I’m trying to write a history for young people. They deserve some form of truth, that is the only holistic way to talk about the Partition.

There is this reoccurring theme of cultural identity in your book and in any conversation about the Partition. In the stories you've encountered, have people come to terms with the fact that they may never really belong to one place, one culture, one identity?

Most people from that generation have resigned to the fact that they will never see their home again. The interesting thing is that if you talk to people from India, they will never say they are from Pakistan, they will just mention the name of the city. The cultural investment is more in the city you are from. My grandmother will still say that D.I Khan is home, we live in Delhi, but D.I Khan is still home. On the other side in Pakistan, if you were a Muslim that went to Pakistan you made that choice, sometimes that choice didn't work out in your favour and sometimes it was a new country and people didn't know what to expect. Once I did this interview in Lahore and this man was telling me that there is a big difference between Indians and Pakistanis. Just when I pegged him as a religious bigot, he said, “how can someone ever really separate you from the soil of your land?” That’s when I thought: how complex is this notion of belonging? For how many years have you buried this very statement inside you? How many years has it taken for it to come out? Even if he wanted to say it, who would he say it to? No one asked them about this lost home in years.

War reporters often suffer from post traumatic stress disorder. In a way, you went back to look closely at a highly violent and tumultuous period in time. On a personal level, what did hearing these stories do to you?

Don’t you think I’m a little unusual? I have become heavy. It’s very difficult to hold onto little segments of people’s lives. My head is full of data, languages, names, houses and unfortunately in the last few years I have lived my material. I don't need to refer to my book to have this conversation because the material is in my head. The problem in that is you hallucinate sometimes, it is upsetting to see what a stifling generation we have become and what an incredible generation we come from. How little of that we have retained. I remember two years ago I woke up from a nightmare and I didn’t even remember where I was. I did so many interviews that week that I dreamed about all of them and they were all in front of me and I had to locate myself for a minute. I have recorded it, but history doesn't belong to me, it doesn't belong to anyone. You have to share it.

How would you describe your brand of storytelling?

Oh, bestseller. I’m joking! Though I have been on the bestseller list for weeks. To be serious, my work is an amalgamation of senses, whether it be through art or writing, it is to find a way to get closer to one’s senses. And memory is also a sense, it is an intangible sense, it’s an invisible sense. For me, this work is about connecting, getting closer to one’s senses, as all art should.

Why did you choose to write this book as a series of conversations with people?

I wrote the book as a series of conversations for the simple reason that I wanted to be in it. There is no point in talking about the past if you don't talk about the relevance of that past. If I don’t put myself in the book and also archive my reaction then what is the point? Then it’s just like any other book of stories. I am also making a comment on the things they are telling me because I have my own opinions being from a completely different generation so removed from it.

You’re looking at the objects that people took with them during the partition, but in a way you are also looking at everything that was left behind. What about the objects that people left behind and still ache for today?

I asked this Sindhi woman this question specifically because you couldn't take much from Sindh, you were searched on the boat. I asked her if there was something she wanted to bring along that she couldn’t, she told me about a swing in her house that she wished she brought along. [Those who left as] children would talk about toys. Then there were things people had to let go of along the way. There was a woman who was from a very rich family, she was coming from Dalhousie to Murree and was bringing along these collections of carpets and silverware. On the way she saw all of these Muslims that had no way to get across the border so she took out all of things and asked the people to come along instead.

I also started thinking closely about what people considered precious or valuable. Through my conversations a lot of objects gained their rightful importance if they were of incredibly mundane nature. They were not appreciated for their survival or their virtuosity, it was just this old thing that they still had with them. I was trying to explain the value of a shawl passed down for three generations to a woman who was focused only on her jewellery when she noticed a stain on it. She started panicking about the stain and that’s when I realized that this incredible object that was just a footnote in your history has become so important because she found a stain on it. What about the stain that you left behind? What about the violence you left behind? It stands for that.

In a way, this book is a study of the word “home,” of what it is, how we feel when we lose it and the value of the things that serve as reminders of it. How has your idea of home evolved?

Let’s just break up this word home. The idea of home is from the physical home. The home of one’s past or dreams or imagination is often a glorified home, it is not really a real home. Maybe that is the narrative that will be passed onto the subsequent generation, which is fine, but the physical home is the home you live in, it is reality. My notion of home is Delhi, there is something centering about the city. My grandmother always says that no matter how far you go, the soil of where you are from will never leave you. I lived abroad for ten years, at first I thought it was very easy to change your personality and become from somewhere else because you have this fresh clean slate. There is something magnetic about the place that you are from, there is also something very humbling to succumb to it. Delhi is like that for me.

You explore the idea of intangible remnants. Discuss the idea of emotions as heirlooms.

The man who was telling me about the Hindu-Muslim thing in Delhi, he did not bring anything with him. Throughout our conversation I kept wishing that he had an object, it was very selfish of me. He had this very ghostly presence about him, he was trying to make me understand that he was holding onto a value of secularism that might not exist today, but in my jaded mind I kept thinking about an object. It was very scary to be confronted with nothing or something larger than what I expected. I didn't have the ability to hold that weight. I had just come to look at things, now I was leaving with responsibility. In that moment, I looked at my hands and thought, they are too small, they can’t hold this weight.

Intangible values are the heaviest because they ensure that you need to do something about them and not just listen. To be privy to a value or a tradition or a custom is somehow to sign an invisible binding contract that you will do something with it. A woman told me about all the women she had to send back at the camps and that was the only moment when I broke down. It truly felt like someone took this really heavy weight off their shoulders and put it onto mine. How do you carry that weight if you have no tangible connection to that event?

How have you come to terms with the fact that you are an intruder in the lives of these people who may be trying to forget this event that happened years ago?

We are very voyeuristic, but how do you make a story from nothing? No story is created from nothing. All fiction is some form of nonfiction. You might not borrow from the things you see immediately but it might be from something you experienced at some point or something you overheard. The human mind absorbs environments and regurgitates them in the process of writing or painting. Yes, I was shadowing many people’s lives. In this case, it is for a social purpose, in the case of other works it might not be. There is something very self-fulfilling and almost selfish in the act of writing. You have been given the ability to mold, more in fiction and less in nonfiction, but still you exemplify certain things in certain ways. You are shadowing people’s lives, you are tiptoeing around the edges of their memories.

One of the stories that has stayed with me is the one about the Punjabi poetess who fell in love with the army man. How did you come to find this story?

This was at the beginning of my research. Finding people who have lived through the Partition is not difficult, but finding objects is very difficult because people don't remember the things that they have now. I told everyone [in my family's bookshop] to ask customers if they still have something from before the Partition. This woman came in whose husband was the chief of army staff and was a very close friend of my father’s. My mother asked his wife if they had a Partition related story in their family. And she said yes, her mother had some utensils and jewellery. So I went to this poetess’s house with the intention of looking at jewellery and utensils and then she told me this story from 1942. She was in Lahore writing nationalistic poetry for this magazine that used to be circulated to all of the Indian soldiers fighting for the British army in World War II. There was this particular soldier in Mesopotamia who got a copy of this magazine with a poem by this woman inside it. This man read the poem and decided he wanted to marry the woman who wrote it. He came to Lahore, to the address that was listed on the back of the magazine, and asked this woman to marry him. They got to know one another and eventually got engaged. Then he got posted in Baghdad and she got a copy of this same magazine with his name posted under a poem. He had not told her that he was also a writer. She read the poem and thought it was incomplete, in the next issue she continued the poem by writing a passage. He then read that passage and wrote another one. This went on for six verses, it was ultimately published as a book called Rohini and Veer Singh.

What is a story that has stayed with you?

Some stories are odder than others and they stay with you. In this Bangla story, the last chapter of the book, this man had lost his memory because of a brain hemorrhage. Over the years before his memory left him he had been telling his wife all sorts of stories. So, what he didn't remember she remembered. As a third-generation person in this subcontinent I remember things for other people because they can’t. I asked her very categorically: why do you remember these things? And she said, “if I don't who will? Who will tell our daughters and who will tell their daughters?” Someone needs to be the carrier of history. There are other snippets like this family rolling up all their jewels and tucking them into the floor, a mother putting a handkerchief in a child’s mouth in the train so the child doesn't scream. A man appears at a well-known family’s house Pre-Partition and everyone says he's fallen from the sky. They take him in because they believe that he has come from god and then create a room in the garden for him with a roof that is made of glass so that he can look at the sky. There is a village in Pakistani Punjab where an entire population of Sikhs converted to Islam because they don't want to leave. These things will always stay with me.

What’s next for you?

I’m working on a novel about an Indian soldier who fights on the Western Front in World War I. How much do we know about Indian soldiers who fought in World War I? We know nothing, that’s worth exploring.

There is this inherently bitter-sweet quality to all of the objects and stories in your book. The idea that these people have reminders of this life, this home, parts of their identity, they will never get back. Is this something you thought about before you started writing the book?

It’s simply: how has no one worked on this? I must work on this. I haven't read my book, by the way. I just can’t read it, I feel like there is another kind of energy that wrote it. When I was writing this book I was in a place where I was ready to absorb all of these things that were forgotten, that were lodged in between the cracks of memory. At the time I realized that it’s not that this generation of people who lived through the Partition don't know how to remember, they don't know how to forget.