I’d like to live in a society where everyone felt comfortable with their sexuality and no one felt bad about their privates. Where adults respected other adults as sexual beings regardless of appearance or profession or proclivity, and no one found anything wrong, in principle, with the habits of consenting adults. But I’d still want sex to feel a bit wrong, because sex doesn’t happen in society: it happens in a private netherworld, governed by a loopy, upside-down logic that makes gross things nice and nice things gross. There are desirable things, and there’s what you desire even though it makes no sense and might lead to injury if you actually try it.

That’s what makes erotica difficult for me: no matter how rich the fantasy, it involves the intellect, and the intellect shouldn’t always get involved. And lately I’ve read a lot of erotica. Two big titles are following up the Fifty Shades trilogy: S.E.C.R.E.T by L. Marie Adeline (aka Lisa Gabriele)--the “Canadian Fifty Shades of Grey,” although the two have little in common besides sex—and Pauline Réage’s classic Story of O, originally published in 1954, which will be reissued next month. The former takes place in society as we're familiar with it while the other never leaves the bog of desire, its narrative logic based purely on drive. And the contrast is illuminating.

S.E.C.R.E.T imagines something close to the utopia described above, and the novel sits well with the social brain; Gabriele, a novelist and TV producer, has been frank about her effort to capitalize on the erotica trend, but she’s done so with heart and a conscience. The novel’s star is Cassie Robichaud, a 35-year-old waitress in New Orleans, who only ever had lousy sex with a husband five years in the grave. She “often thought of this accidental celibacy like it was a skinny old dog, left with no choice but to follow me. Five Years came with me everywhere... parked itself beneath every table of every tepid date I went on, slumped at my feet.” It happens that way: the longer one goes without, the harder it gets, until the whole ordeal of arousal no longer seems worth the embarrassment. This is why Cassie refuses a date with her handsome boss—she likes him—and why he ends up with a younger, sexier girlfriend.

Cassie’s homeliness gives off a vibe that attracts Matilda, a beautiful, witchy woman of “perhaps fifty or a well-preserved sixty with red wavy hair, wearing a pale coral tunic.” She represents S.E.C.R.E.T, an all-female society devoted to helping dowdy women become sexually whole. The group isn’t shadowy at all, but rather bourgeois and civil thanks to a trust fund endowment from a feminist painter, and it operates a ten-step program designed to walk members through their fantasies with the aid of handsome and competent stud recruits. The tenth step is a choice: you can either stay in S.E.C.R.E.T., mentoring other women (as Matilda does Cassie), or you can enjoy a better monogamy having sown your wild oats. Either pair up and live happily ever after, or enjoy a lifetime of female friendship and no-strings-attached sex—also happily ever after.

The book has a moral message, and it’s a refreshing one. As Gabriele told Anna Maria Tremonti on The Current, “after I finished the first draft, I realized, I’m writing a book that’s really encouraging women not to develop emotional attachments to the men with whom they have just sexual relationships.” Matilda says as much to her protege: “Sex creates chemicals that can be mistaken for love. Not understanding that about our bodies creates a lot of misunderstanding and unnecessary suffering.” Cassie, under her guidance, learns the value of waking up alone, and comes to enjoy her flings for what they are. And the novel, at root, is a social fantasy: the fantasy of being able to live your fantasies, of a world in which this approach to sex were easy for women. Because it’s not, really—not because we all yearn for peaceful monogamy, but because the world tends to lacerate our sexual confidence and slap us with sexual expiry dates, then insist that what we really want is peaceful monogamy.

So Gabriele imagines the conditions for successful promiscuity. First is a support network, of women who have time for you and who aren’t going to mosey off once they partner up. Second is an endless supply of partners who know what they’re doing—men who’ve applied the same effort to giving head as straight girls tend to devote to the art of the BJ—and who are mature and diverse enough as a bunch that each sorority member is taken care of, regardless of age or body type. Finally, there’s a social context in which no-strings-attached sex is perfectly acceptable and not awkward or perfunctory unless you want it to be. At heart is the notion that our sex lives complete us from puberty until death, which is radical common sense.

The sex in S.E.C.R.E.T is as nice as its context: handsome men make Cassie come and then tell her she’s beautiful. This attention buoys her self-esteem and gives her a new lease on life, and it’s all very nice, but I read it with both hands: if a beautiful masseuse showed up at my apartment and offered me head, I might not say no, but to get off I’d have to imagine him doing something unconscionable instead. S.E.C.R.E.T’s credo is “No Judgments. No Limits. No Shame,” and I love that in theory; but in practice, shame is kind of a magic ingredient. I felt a little ashamed reading Story of O, which also hinges on a secret society, albeit one composed of men who enjoy beating up willing female participants.

O is a fashion photographer who is taken by her lover, René, to a chateau in Roissy, at the outskirts of Paris, where she’s gussied up in a corset and clogs and savagely violated by multiple assailants. Back in Paris, René “gives” her to his English friend Sir Stephen—who, in my mind, resembles the guy on Seinfeld who tells Elaine it’s “proper to say pardon”—and the abuse metastasizes. The novel was written by Pauline Réage, aka Dominique Aury, a distinguished critic and editor, for her older lover, Jean Paulhan, a member of the French Academy. He was married, and a womanizer, and an admirer of the Marquis de Sade; Aury was single and 47. “I wasn’t young, I wasn’t pretty,” she told John de St. Jorre for a 1994 New Yorker profile. “It was necessary to find other weapons.” She composed much of it in bed, with a pencil, in the apartment she shared with her parents; Paulhan, who’d been skeptical, at first, of a woman’s ability to write erotica, encouraged her to finish it and then found a publisher.

Story of O has been condemned by some feminists—notably Andrea Dworkin, who saw it as prescriptive. In his New Yorker article, de St. Jorre asks Aury if her fantasies were male-specific. “I’ve always been reproached for that,” she replies. “All I know is that they were honest fantasies—whether they were male or female, I couldn’t say. There is no reality here. Nobody could stand being treated like that. It’s entirely fantastic.” While it may have been written for one man’s arousal, the novel reflected its author’s tastes: by de St. Jorre’s account, Story of O is based partly on fantasies she had since her teens, which—assuming they involved some form of submission—would put her in either the healthy minority, or the slight majority of women surveyed since the ‘70s. You can abhor something socially and still desire some imaginary figment thereof.

What we want in sex is not necessarily what we want in the world. Often it’s the opposite, and past the golden gates of consent, actions arguably lose their moral character. But by the end of Story of O there are no such gates, no division between sexual and social life. At Roissy, cloistered and chained, O “had been able to hide behind the feeling that she was undergoing some other existence or perhaps that she didn’t exist at all.” Back in the real world she holds down a job and keeps her own apartment, but when Sir Stephen receives a spare key, what had once been a sexual arrangement proceeds to “contaminate all the habits and circumstances of her daily life.” An altered state becomes her reality (again with her consent, in the sense that she’s free to leave her “masters” at any time).

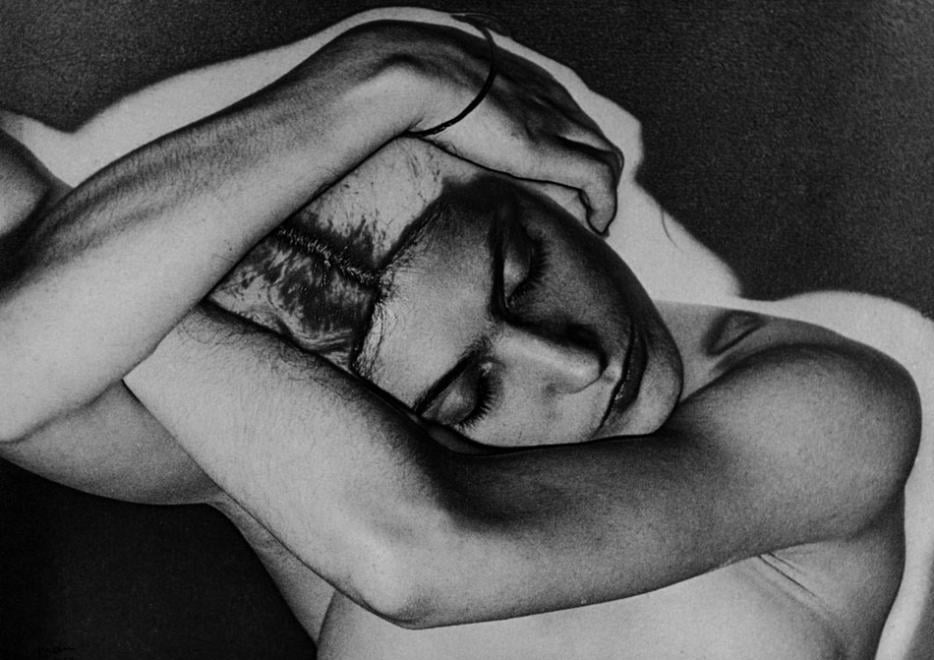

O is branded with Sir Stephen’s initials and pierced through her labia with heavy pendants bearing his insignia. I cringed a little as I read these passages, but the quote that shocked me was this: “O will be happy to be torn.” It shocked me because it’s a thought I’ve identified, and chucked, from an inner conveyor belt of potential fantasies; it’s the thing you least want to happen even while pretending it might. Sex needs limits to stop short of or transgress, which means you get off sometimes by imagining things you’d really hate to go through. I think this is what Lacan meant by jouissance (I think because I don’t know for certain what Lacan meant by anything): that desire to vault the boundaries of your own pleasure, beyond which are horrors by any rational taxonomy. There are no such boundaries in Story of O. The risk of injury and annihilation isn’t just seasoning; it’s an open vortex.

Story of O is a literary novel, and Aury offers a lucid, dexterous account of O’s motivations, which is both comforting and not. It’s often been said that O’s submission is religious in form—she hands her life over to a higher power, preferring to be “the lucky captive upon whom everything was inflicted, of whom nothing was asked.” Then there’s the perverse allure of the worst thing you could possibly do, or have done to you—O observes of a fellow slave that “her proffered sweetness, her helplessness cried out for wounds as much as caresses.” In other words, cute things sort of make you want to crush them. I was struck by Aury’s description of O as a “butterfly impaled on a pin,” because this is exactly how I expressed my attraction to a weird guy who started talking to me once on the streetcar. He struck me as a loose cannon, and I had no intention of going home with him. But I had a good time thinking about it.

Story of O contains no compartments, no apologies, no rules of engagement—and that’s precisely what makes it such a successful fantasy. Compare it to Fifty Shades of Grey, which contains more precaution than risk: pages and pages of legal negotiations, as Anastasia Steele and Christian Grey formalize their “hard and soft limits”; gynecological consultations and birth control prescriptions; sex scenes in which the “foil packet” is a supporting player. And very little pain, after all that, at least in the first volume. Or compare Aury, with her moral pokerface, to novelist Tamara Faith Berger: her 2012 book, Maidenhead, offers an excellent, politically difficult fantasy in its first half and spends the second trying to justify itself. But Story of O gets right to it. There are no morals, no politics, because neither are relevant: the whole thing is a fantasy.

This is understood, but does that make it easy to stomach? As much as I enjoyed Story of O, as both a fantasy and a novel, it disturbed me—I can suspend my morals and my politics for thirty-minute intervals, say, but not for 203 pages. I don’t believe that an erotic novel needs moral scaffolding, necessarily, but maybe I need that scaffolding: some hint of conflict on the author’s part, a few narrative compartments to remind me that it’s just sex, and no one here really believes that women are inferior, and all the rape isn’t actually rape because it’s consensual, and we all know that rape in the real world is a horrible act of violence that people, including people you love, actually have to live through.

I like scaffolding for the same reason I like to see the villain punished at the end of the film: because the author stoked a demon in me and I need her to shoo it out. And because at the end of the day, whatever we get up to consensually—be it hot oil massage or 24/7 BDSM—we’re living in a society. If our society looked more like it does in S.E.C.R.E.T, maybe I’d have found Story of O easier to read.