Will Self writes books that no one else would even imagine. The title story of his debut collection, The Quantity Theory of Insanity (1991), postulates that there is only a fixed amount of sanity in the world at any given time. Grey Area (1997) substitutes all the apes in the world with humans and vice versa; How the Dead Live (2000) contends that when people die, they just move to another part of London. And The Book of Dave (2006) presents a flooded future London where the writings of a misanthropic 20th-century cabbie have become scripture.

Underlying Self’s high-concept literary fever dreams is fierce cultural commentary. At times, however, this—and his writing itself, for that matter—has been overshadowed by his image. Colin MacCabe’s London Review of Books review of My Idea of Fun (in which sick jokes come to life) opens with a paragraph addressing the dust-jacket photo: “This is not the author as good guy but the author as knowing addict.” His drug habit (he was kicked off John Major’s campaign plane in 1997 for taking heroin in the washroom, and got clean in 2000), his TV and radio appearances (delivering trenchant, cavernous-voiced salvos on shows from Have I Got News for You? to This Green and Pleasant Land: The Story of British Landscape Painting), and more recently, his long and improbable walks—including from the airport to his hotel in every city of a North American book tour—have all made the news.

But with the publication of the Booker-shortlisted Umbrella (2012) and this year’s Shark, his writing is gaining a newfound and widespread respect. The two novels, part of a planned trilogy that will conclude with Phone, are demanding; they’re long works without paragraph breaks, using a stream-of-consciousness narrative derived from modernism, and rich to the point of bursting with cultural and historical allusions.Central to both novels is the psychiatrist Zack Busner, who has been lurking in Self’s work, bumptious and slightly sinister, since the beginning. The novels imagine links between key 20th-century events and the outbreak of particular kinds of mental illness.

Ever the contrarian, Self believes that the increased attention being paid to his work by critics comes at a time when serious literature has become culturally irrelevant. In his study on the top floor of the south London house he shares with his wife, journalist Deborah Orr, Self perches his elongated frame incongruously on a small stool. Over a cup of tea, Self discusses Shark as both an end-of-days flourishing of his talent, and an organic outgrowth of a series of literary obsessions—sick jokes and all.

It has become a trope of the “interview with Will Self” that journalists will start by describing how intimidating they expect to find you, only to discover you’re really not that scary. What do you make of this?

Will Self: Well, I know I'm not really that scary, but I concede that the great height, the cadaverous appearance, the reputation for take-no-prisoners contrarianism and high-concept bohemianism, the sesquipedalianism, the insistence on intellectual rigour—all of these can, perhaps, be a little intimidating. However, while I can be ferocious towards those who are in positions of power or privilege, I have no beef with anyone else, and I don't suffer fools at all. I positively enjoy them.

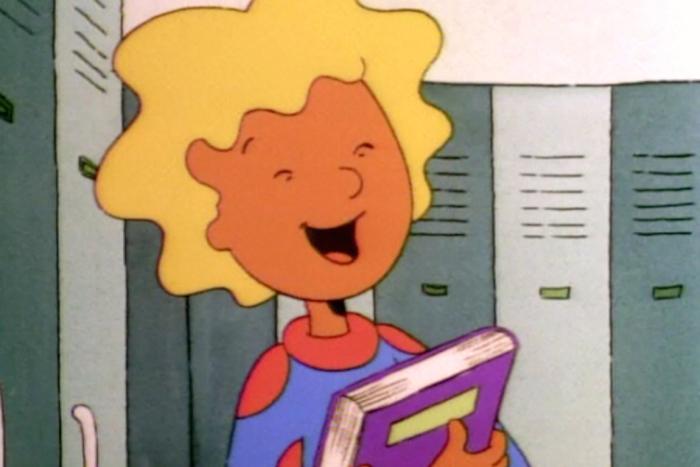

Your first book—well before Quantity Theory—was a 1985 collection of your Slump comics, which you’ve called a “middle-class synthesis of Andy Capp and Goncharov's Oblomov.” What set you on the path to drawing comics, and do you see any continuity between that work and your later prose?

I always drew cartoons. I began when I was a kid. When I was at university I started drawing them for publications, and people seemed to like them. When I left I hawked them round newspaper offices and got some work. I was never a natural draftsman, though (I taught myself to draw perspective), and it was the ideas that really interested me. I already wanted to be a writer, but, like a lot of young people, I was intimidated by the prospect of putting finger to key. Cartoons were a soft entry to creativity for me. It's really quite a limited medium, cartoon—whatever people say about graphic novels—and although my professional cartooning career really only lasted for about five years, it was long enough for me to feel I'd said all I wanted to say in that medium. Meanwhile, the captions were getting longer and longer, while the drawings were becoming sketchier and sketchier, so that eventually I was able to abandon this inky prosthesis and walk on my own metrical feet!

Last year, you told The White Review, “I was trained as a philosopher so that’s how I approach fiction I suppose.” How formative, then, were your Oxford years in terms of your writing? (And is it true that, as a Sunday Times Magazine profile from 1993 asserts, you went to only one lecture?)

I went to two lectures, one by P.F. Strawson on Kantian metaphysics, and one by a moral philosopher called Lucas, [though] I can't recall what that one was on. The Oxford system isn't really lecture-based anyway: you're set two 3,000 word essays a week, and you read them aloud to your tutor, usually alone. It's very intensive, and lectures aren't really germane (there's too much reading to do anyway), but the discipline of studying and writing that much, every week, undoubtedly hugely assisted me when it came to being a writer.

At the conceptual level, well... it wasn't so much that philosophy is a good training for a fiction writer, it was more that it wasn't English. I believed then, and still believe, that in my case at least a literature course would've been inimical, because it would've simply confirmed in me the prejudices of critics, who always look at the fictive from the wrong side of the one-way window...

In his book Understanding Will Self, M. Hunter Hayes speculates that you began writing in earnest after your mother’s death in 1988 due to “a combination of grief and a sense of relief at no longer having to worry about obtaining her approval or scorn with [your] literary endeavours.” Would you agree?

Up to a point. There's no doubt that my mother's death was a factor, and for the reasons Hayes adduces, but equally—if not more— significant was the fact that my then wife was expecting our first child. I had a strong sense that I was about to be superseded, and I hadn't done anything of significance yet! So, the baby's imminent arrival drove me to it.

In your early career, you became best known for your short stories, and yet you seem to have abandoned the form of late—drastically so, in favour of long, one-paragraph novels. Do short stories still compel you?

Yes, I love short stories, but publishers don't want them—the one concession I perhaps make to the marketplace. And anyway, novels are in many ways more absorbing and exciting to write. I have a big file of short story ideas I've accumulated in the past few years, and the plan is to sit down and write enough for a really fat collection once I've got this pesky trilogy out of the way.

Around the time you wrote Liver, you told me you’d given a reading from the story “Leberknödel” that had made people cry, and that this meant more to you, making people laugh. Do you still feel that way about the value of emotional response when you’re giving readings, or indeed in your writing? And to what extent do you consider yourself, at this point in your career, a comic writer?

If a writer can't do humour at all then he's not really firing on all cylinders, or adequately responding to the human condition—which is largely absurd and risible. That being said, I think I wrote more jokes when I was younger because: A) I found the world more absurd and risible, and B) I knew I could do it, and even though I couldn't witness the people laughing, I knew they very well might be, and I found it reassuring being able to provoke some sort of response. (It's the same thing with public readings—the temptation is always to read the funny bits.)

Your journalistic broadsides against George Orwell, hipsters, and other figures attract a degree of controversy, but in general, you appear to be less of a divisive figure than in the ’90s, when certain critics called your work “nasty.” And yet reliably, in the below-the-line comments to your newspaper and magazine work posted online, people are driven either to attack or defend you based on your unapologetically expansive vocabulary. To what do you attribute this ongoing war of —and about—words?

Well, I think not knowing the meaning of something they read upsets people—it makes them feel small and ill-educated, and they react very negatively. But I also think there's a general antagonism towards the intellectual life, particularly in England. This is a recent phenomenon, in the sense that it's an aspect of a fully-literate culture in which everyone effectively has access to almost all the knowledge in the world. In the past people had to strive to find things out—now they can get it all with a few keystrokes; knowing this, and understanding their own great intellectual indolence, people are outraged by the prospect of someone who does make the effort. Also, there's a strange sense of intellectual entitlement that comes with this facile culture: people think they should know everything without having to try - in the same way they can buy everything effortlessly, if, that is, they have the money.

You mentioned in The Guardian that when you were casting around for an idea for Shark, you encountered Jaws, and both Peter Benchley’s novel and Steven Spielberg’s movie adaptation struck a chord. In general, do you always start with something thematic or conceptual, or is there ever a narrative germ in your head that you want to work out?

I still start with ideas, by and large. So just when I’d finished Umbrella I thought, “This is a story that goes on through the 20th century, in this relationship between illness and technology—we can do something more with this idea. The anomaly between the novel Jaws and the movie [where in the latter, one character mentions having been on the USS Indianapolis, a ship that transported uranium used in Little Boy, the Hiroshima bomb, and was later sunk by the Japanese, with hundreds of its shipwrecked crew eaten by sharks] gave me a lot of narrative. OK, so you’ve got a guy [Shark’s character Claude] who’s on the Indianapolis, and you’ve got a guy [Michael] who’s in the Enola Gay—what if they meet?”

Concurrently, I had thought about the episode in Umbrella where Busner says he stopped using LSD after this awful occurrence in the Concept House: he says he’d been standing in the bathroom looking in the mirror when his nose detached itself from his face and started cruising around the outside—and that vignette had stayed with me. There’s been talk of the Concept House [akin to R.D. Laing’s Kingsley Hall in the 1970s, a residence for psychotic patients] right through the oeuvre, back to 1991, but we haven’t spent much time there, and I [thought], “Well, we keep talking about this fucking Concept House; let’s get in there!”

So the answer is, it’s hard to know which comes first. The analogy is fission. I think of writing novels as inherently synthetic, as a joining together of certain kinds of ideas where once they reach critical mass, the subsequent explosion will be way more than the sum of the parts, because of the morphology of the explosion, the shape of it. An idea will come in about narrative, an idea will come in about theme, a philosophic idea, an idea about character, and then it’ll just get too heavy. It’ll go, “Boom!” That’s the point at which you start writing.

Speaking of the relationship between illness and technology, how does this work in Shark?

In Umbrella, the technology is mechanization, the disease is encephalitis lethargica, and the individual is Audrey. The idea is, can an individual’s pathology be in some sense an instantiation of a societal phenomenon, which is this new technology? And it’s the same idea in Shark: the new technology is nuclear fission, but it all relates really to the card that Busner sends to [philosopher Theodor] Adorno early on—he says, “You say no poetry after Auschwitz; I say no love after Hiroshima.” After Hiroshima, all love becomes a double bind, ‘cause you can’t love another person in a world in which you might suffer imminent anthropic destruction. A world that can be destroyed by humanity like that [snaps his fingers] is not a world in which it’s possible to love. [Psychiatrist R.D.] Laing borrowed very strongly on the idea of the double bind as one of the causal factors of schizophrenia: his argument is that the family is a cockpit of double binds, of people constantly going, “Yeah, but I love you!” and saying one thing and meaning another, and the child becomes trapped, has nowhere to go emotionally.

I’m suggesting that the double bind becomes global after the bomb, and these flamboyant pathologies, which are post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis, and addiction, are all post-Hiroshima phenomena. They take on a particular emblematic form of this universal double-bind. Michael, Claude, and Jeanie, who represent the pathologies—it’s not a function of their individual experience necessarily; it’s a function of their position in society and in time. And then Phone will be digital media, the Iraq War, and autism. [laughs] So I’m really looking forward to that!

So to be clear, you’re suggesting that addiction after Hiroshima takes on a particular cast—

Yeah, the particular savagery of post-1945 addiction, which increases exponentially in instants, is a function of a cosmic double bind: the object, which presents itself as desirable, is in fact pernicious. And that’s how the addictive object starts to play out in the psyche. You don’t need to have all of that in mind, because the novel has a narrative. It does have several plots.

There’s a predator/prey relationship running through Shark.

Yeah, there are various deep-level schemas in the book that I don’t expect readers necessarily to get [laughs], though I hope some poor academic will in the future. Jeanie [a young, drug-addicted patient in the Concept House] is the real shark, in the sense that she is somebody who, simply as a function of her nature or nurture, is destructive of herself and others. She’s a destructive element, but she’s also a free particle. Each group she moves into, she knocks somebody out of it, just as in a process of nuclear fission. So each of the groups is actually conceived and patterned on a Uranium-238 nucleus. The whole process of the book can be conceived of as a linguistic model of nuclear fission. I don’t necessarily expect people to see that.

There is much in Quantity Theory that you’ve mined in your later work: ideas, themes, obsessions. Maybe we can talk about a few of those. Let’s start with Zack Busner, who keeps reappearing. It’s as if he has a life of his own. He has his own Wikipedia page.

Does he? [laughs]

So what is it that has either made Busner useful to you or stuck him in your psyche as a writer?

I think it’s those two things. One is that he’s useful, early on as a stereotype or a hieratic figure. In Quantity Theory, he’s representative of the idea that psychiatry and the psy-professionals generally are like a priesthood, mediating between the noumenal and the phenomenal worlds. They’re policing the boundary between sanity and insanity, between immanence and transcendence. Then he’s in a few stories in [the 1994 collection] Grey Area. “Inclusion” is a satire avant-la-lettre on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and Prozac; there, he is an agonist [who] still largely has an emblematic role. In Great Apes, he’s more a parody of Oliver Sachs, but it’s still fundamentally about the idea that there’s something exploitative in the relationship between psy-professionals and their patients.

And then in [2004 collection] Dr. Mukti, we can never be sure whether we’re seeing him with any objectivity at all; there’s this whole idea that he’s part of a Jewish conspiracy against Mukti, and paranoia, and “Is this really happening?” In [2010 novel] Walking to Hollywood I subject him to a postmodernist take and say, “Well you’ve thought all along that this was a fictional invention, but in fact he’s real. This guy really is my therapist; that’s why I’ve written about him so much over the years.” Maybe bringing him into a therapeutic relationship with the character of me in the book did something to me, and when I got to Umbrella, I suddenly wanted to be in his head. By that point, he’s got a proper backstory.

Each time I get to one of these novels, I think to myself, “Do I have to have Busner? Can’t I have another psychiatrist or a different character altogether? Why is he recurring in this way?”

Each instantiation of Busner has called for the next, but [also] very early on—probably when I wrote Quantity Theory, I wanted the text to exemplify a thesis about fiction and reality. I’m not saying it’s an original philosophic idea, but I’m not a Stendahlian naturalist; I don’t think that art is the mirror of life, and I think that there are real problems with naturalism as a concept. It seems self-defeating, and I’ve always understood that, and that’s why I’ve never written naturalism as commonly understood.

I couldn’t even really get going, trying to write something that claimed to be a common-sensical representation of the common-sensical world that we all know, specifically because I’ve never seen [realism] as a vehicle for truth. My view has always been that truth lies in art by proposing fully alternative worlds, because you can see the relation, and that truth is a function of coherence, not correspondence. We feel that things have a veracity when they’re linked to other things that seem to stand into being with some veracity, so the stories of Quantity Theory all relate to each other, but with different ontological levels. So in one story a character, say Busner, will appear on television, being watched by another character, or a theory that is enunciated in one of the other stories will be spoken of as if it’s an established fact, so that basic structure or philosophic idea is present in Quantity Theory, and all of the rest of the work is an elaboration, which is why more or less all of it connects. Only a handful of narratives stand alone: The Butt, Dorian to some extent, and one or two of the stories, but I would imagine 80 percent of the work is coherent in some way.

Does the fact that you gave Busner a backstory and fleshed him out reflect a development in your writing? You’ve become more interested in character.

I think I am, but I can’t come at character circumstantially, and that’s why I’ve flipped into stream-of-consciousness. Because of my caveats about naturalism, I could never get to character by saying, “Mike Doherty sat in Will Self’s room.” A sentence like that would seem preposterous to me. It would seem to beg so many questions that I could never get further. So the only way I could ever get to being interested in Will Self or Mike Doherty as characters was to come from inside them, so I’m still not thinking, “Oh that’s an interesting character. I wonder what his or her story is.” Jeanie in Shark is not even a character. She is based on extensive interviewing with a real person.

Was that the person you mentioned in The Guardian was “the woman with whom I'd begun using heroin in the late 1970s”?

Yeah, somebody I really know, and a lot of the stuff is her story. I think that’s another thing that people really don’t get about writing novels: the degree to which they’re aleatory—it’s found materials. I already had this extensive interviewing in hand with an addict; I looked to fit her into the story. And since the character I wanted her to be is someone who fits into things and then fucks them up, she’s a perfect character anyway, but I would never have arrived at her by planning her top-down. She has to arise organically.

So in answer to your question, I don’t think I’m any more interested in the conventional way of thinking about character than I’ve ever been, but I’m much more interested than I was as a younger writer in phenomenology, in the texture of lived being and thought.

Towards the end of Shark, Jeanie reflects on how much she loves London. Your work has been with London since the first story in Quantity Theory, “The North London Book of the Dead.” Could your work only have germinated in London and been set here?

I think it could have come from any big city. Big cities seem to bring into very sharp focus the distinctions between freedom and necessity, between individuality and just being part of a swarm. You can look at a big city with Koyaanisqatsi vision and think, “This is just like a termite nest. It’s just the function of social insects.” A lot of my ideas feed off those kinds of profoundly uncanny feelings that are only really present in the minds of big-city dwellers. And that relationship between modern standardization—going back to Taylorization (time in motion, the assembly line) and mechanization (big, systematic moieties of people who all do the same thing at the same time)—and the existential predicament of the individual seems very much what my fiction is concerned with.

The actual furniture of it, like Willesden, or the way in which I write about London—that’s all actually subordinate to those kinds of ideas for me. It’s not the particularity of London. I think London is just a really big city with a history. And I do love London. I’m powerfully ambivalent towards it. It’s not a mixed love at all, but to me, the object of my affection is less important than the nature of the affection. It’s too late now to shift to another city. The Book of Dave was my plighting my troth finally, just saying, “This is it. I’m stuck with London.”

Until it floods!

Yeah. Up until then I did, both in life and in art, think, “Why the fuck can’t I get out of here? I’m free.” But after The Book of Dave I just accepted that that’s it.

The Book of Dave is perhaps the most negative portrayal of London in your work.

It is in a way, but paradoxically I thought of it as a love letter to the city. Maybe hatred, contempt, and alienation is the best form of love a city can expect at this point in our history. It’s like people who work in therapy say the worst thing you can do to a child is neglect it. Abuse is actually better than neglect, so maybe abuse is the best kind of love I could offer to London. Certainly at the time I was writing The Book of Dave, I was really irritated by the city. It drove me mad. It still does. Again that’s the paradox: a lot of the walking is a therapy to make it possible for me to live in the city. Because I’m oversensitive to the material conditions, the practicalities of the city. I can’t sit in traffic jams; I’m acutely conscious of time in motion and money; I can’t ride in taxis, for example. It’s torture to get a cab.

Because time is money?

Time is money, and I know where I want to go, and traffic, and everything. So a lot of the psychogeography and the Situationists’ idea of the dérive was therapeutically applicable to me. It was a way of making it possible for me to survive in the city, a kind of urban survival kit. It’s a very, very deep ambivalence.

And that’s why you made Dave a cabbie.

Yeah. Well the most ambivalent figure of all, the person who knows the whole city but is in some senses ignorant was my friend Harry, who helped me with the research, who’s a cab driver. He said, “Most cabbies, Will, [are] ignorant, lairy”—a great London word—“cocky, and racial” (racist).

And yet they know the city so well.

Yeah. Of course the whole dialectic of Dave, his redemption, is through a dérive—it’s when he walks out of the city that he discovers his spiritual being. He feels The Knowledge falling out of him, so the paradox is, to know the city as a material entity is in many ways to be a tool of what I call the man/machine matrix; Guy Debord called it the spectacle. But by undertaking this dérive, he rediscovers his being. I think he’s a sympathetic character by the end of the book.

On the cover of the book is a girl with shark’s teeth. You’ve long been preoccupied by the grotesque—particularly the morphing of a human into an animal, whether figuratively or, in Great Apes, on a literal level. It looks at humanity in a context that is often disturbing to us. Is that specifically tied into your Swiftian satire, or do you think there’s something more atavistic about it?

Well certainly the straightforward Swiftian thing remains implied in my writing. What you get in Gulliver is essentially an anthropologist’s perspective on humanity: it’s that great phrase Oliver Sachs used for his book, An Anthropologist on Mars. My authorial perspective in a lot of the texts has always been that of an anthropologist from another planet approaching Earth. If you view human behaviour as a subset of animal behaviour, then inevitably it appears grotesque. It only appears non-grotesque looked at from within self-censoring human perspectives, [including] books and artworks in which nobody shits.

I’ve said this many times but I cleave to it still: most people in novels are impossibly high-minded and non-animal. They often seem to be to be like disembodied spirits. Probably the most grotesque scene in Shark is Jeanie’s Caesarian intercut with Hooper cutting open the shark in Jaws—it’s just a corrective. To me it’s not grotesque; it’s natural, actually. The way we think about our bodies is confused, graphic, organic; in art, it’s so often represented as curiously inorganic and removed from it.

So I’ve never thought about myself as a conscious practitioner of the grotesque at all, but maybe I’m deluded. I’m always slightly surprised by people who say, “[Your writing is] so grotesque and weird and horrible,” and I just think, “Well, life is kind of grotesque and horrible.” I’m constantly flinching away from it. This guy knocked me off my bike the other day, and I fell on my hands on the gravel and the little bits of gravel stuck in the flap of skin coming up from my hand. What do you do at that point? Do you look at it very intensely, the flap of skin, back and forth, saying, “That’s interesting. That’s flesh.” No! You put a fucking bandage on it and stop looking at it! Because you don’t really want to think about the organic basis of your existence too much, and it feels immediately grotesque.

Liver is really a whole book that deals with the organic basis of existence.

I’m not about to leave it alone either. I think it’s fascinating, again just looking at it—it’s my word of the moment—phenomenologically. The way in which our mental content reflects that essential instability in our relationship with embodiment is endlessly fascinating to me. How can we articulate that?

This book portrays instability, and yet it’s not surreal in the sense of a lot of your earlier work.

Not at all.

And yet there’s a long scene where people are hallucinating on LSD, and as we get into their heads, we get the impression that reality is fluid, hard to establish as something derived by consensus.

Yeah, that’s right, and the way we think about our lives necessarily partakes of social and culturally sanctioned schemas, whether they’re as simple as the calendar or how much we weigh or what’s written on our cv. Our inclination to place ourselves in that common-sensical structure is always being undermined by our actual mental content. It’s Magritte, isn’t it? Or Freud: “In our dreams, we’re all surrealists, but in our lives, we’re bourgeois.” I think we’re all surrealists. But my argument is that Shark is a deeply naturalistic novel.

With so many cultural references and allusions that it demands rereading.

Or I’m going to have to do an annotated text. [But] Shark is like Janet and John compared to Ulysses.

I’m mugging up at the moment to teach Ulysses [as professor of contemporary thought at West London’s Brunel University]. It’s hard to see the particular form that literary criticism has taken as we’ve moved on through the 20th century as not being a response to the challenge that Ulysses presents to the critic. It couldn’t exist nearly in the substrate of ordinary readers; it’s too complex.

The list of allusions in Ulysses is longer than Ulysses. But I’ve never been through it and decoded every single allusion. I’m doing that at the moment, and I think very, very few readers apart from academics ever have. And even reading now some of the academic articles on it, I can see that they haven’t done it. So there’s no way that the text could exist just in a reading culture. Ulysses would seem to imply the removal of narrative art from the purlieu of a living culture altogether. It can only exist in a quietistic scholarly culture. It’s like what Deborah [Orr, Self’s wife] said when she read Umbrella: “It’s an insult to working people.” Because there’s just not enough time to read something this dense in anybody’s life under the conditions of late capitalism. In a sense late capitalism also only allows for Ulysses because it provides enough division of labour—that some people’s job can be to read Ulysses. Mine, for example!

At the same time, fans of popular literature often look for more and more layers from their worlds—Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter…

It’s no accident that fantasy is what attracts that. The grand tradition of literature presents us with the idea that a literary work can be a synecdoche: it can represent the entire world while being a viable part of that world, and the things that people dedicate their time to are alternative worlds. And that grand tradition—you don’t hear American writers talking about The Great American Novel anymore. There’s this assumption that it’s no longer possible to do that.

The impetus to consume narrative that’s provided by sex or violence or essentially child-like gratifications—that’s never going to go away. But what the grand tradition of literature does, which is something quite different, can’t be done without a consciousness that doesn’t have the web.

Does the work you’re doing at this stage of your career feel to you like an end-of-days flourishing? Your earlier books were adventurous in their content and style, but in terms of form—your work starts to take risks only when you reach Walking to Hollywood.

It is an end-of-days consciousness, absolutely.

Is that a liberating thing, or a rage against the dying of the light, or somewhere in-between?

Well, look at it from my point of view. I don’t think I’m a bad writer; I think I’m pretty good. I’m getting there. My books are worthless. Fifty or 100 years ago, at my point in my career, I could reasonably expect to be earning some royalties. I’m not earning any. Fifty or 100 years ago, if I had any kind of ego, I might reasonably expect posterity. It would not be unreasonable at this point in my career. I’ve got no chance of it—only as a screen trace or a link. I haven’t got the possibility of canonical posterity because the canon’s not going to exist in that form anymore. So personally, emotionally, the least good parts of me are pissed. But the better parts of me are excited and amused and think it’s fun to write these full-stop-type books, saying, “Yeah, this is fucking coming to an end; let’s go out with a grand, bravura display of what this form can do! Let’s squeeze the last drop from it and try and do something exciting!” But it’s with a consciousness that is very unlikely to be part of an ongoing living tradition.

You can say that Joyce’s experimentation, which included the adoption of new narrative and other technologies into the form of the novel was an anticipation of all of this. He wrote a hypertext novel. He anticipated what the form might be like in a post-codex age, and now it’s come along. We can’t be like Joyce—Joyce’s novel is a skeuomorph. It’s what a hypertext novel would be like if the codex only existed. It’s historically impossible to do it now. You get my drift. [laughs]

I think in our children’s lifetime, the serious novel will be as I said in the Guardian essay, an emphatically minority interest. The writers of my generation are simply not accorded the personal respect that the generation immediately preceding us are, and I think that’s because at an ulterior level, people are aware that Amis, Barnes, Rushdie—they’re pure writers because they only exist in this codex world, and I don’t think this is ever articulated consciously, but everybody who’s 55 or under is polluted by bidirectional digital media. We’re not writers anymore. We’re not really writers. We’re something else. We’re transitional figures. [laughs]

Do you feel that you’re doing your best work now?

Yeah, I think probably. What I can do now as a writer, I just couldn’t technically do [before]. A lot of it’s to do with grace notes. It sounds odd to speak of economy when I’m writing these huge books, but it’s actually to do with how to indicate a character or to indicate a lot with very little. The characters in Shark, I feel, are very alive, but you get to know them through the accretion of minutiae, not through any grand statements. I think I am more interested in character purely from that instrumental direction. I know how to make people believable on the page better.

So far, Umbrella and Shark have garnered nearly across-the-board enthusiasm from critics. How do you feel about your most challenging books’ being your best reviewed?

Well, I'm pleased, of course—but I always cleave to what Oscar Wilde said: “When the critics are divided the artist is in accord with himself.” You really want a book to arouse ambivalence, because that way you know it can't be assimilated (and therefore neutralised) by the evanescent cultural mulch.