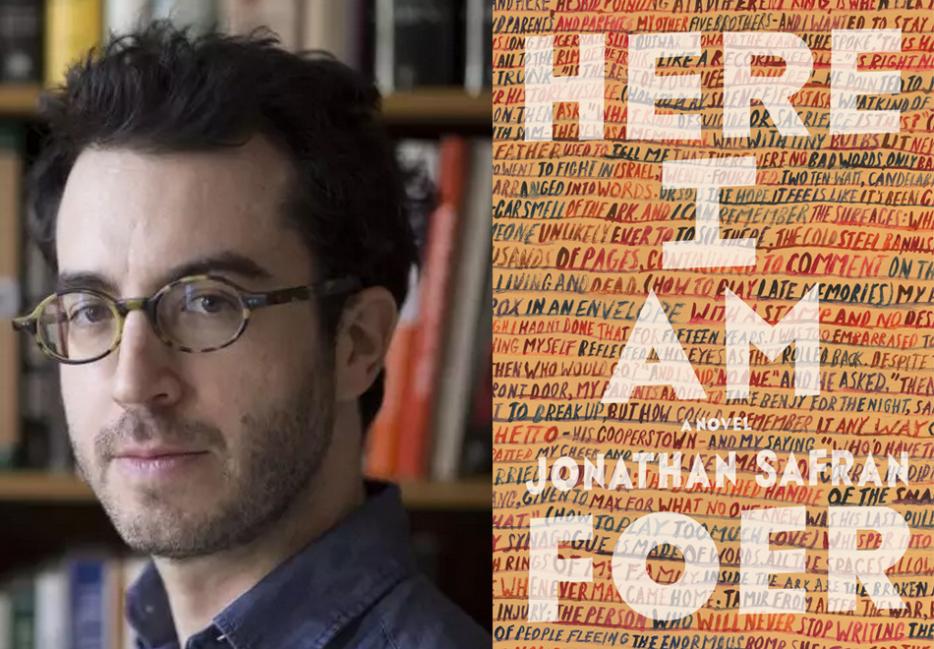

Since the release of his last novel, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, Jonathan Safran Foer has published two books (the pro-vegan tract Eating Animals and the art curio Tree of Codes), promoted the movie adaptations of his first two novels (Extremely Loud … and his debut, Everything Is Illuminated), taught creative writing at NYU, and organized a campaign by Chipotle restaurants to print writing by eminent authors, including himself, on their paper cups. Now, eleven years later, he’s returned to novel-writing with Here I Am.

A great brick of a book, it tells the story of a Jewish couple in Washington, D.C., whose marriage is disintegrating. Autobiographical elements, Foer insists, are coincidental—Jacob, Julia, and their three sons, he says, don’t in any way map onto Foer, his ex-wife Nicole Krauss, or their two boys. Nor, he says, is it particularly significant that Jacob Bloch is an unhappy TV writer—much as Foer himself might have been had he followed through with All Talk, the show he was developing with HBO in 2012. Instead, he turned his attention back to literature, although Here I Am also incorporates a story bible for a fictional TV series, and it’s shot through with the kind of barbed, witty dialogue that might have made All Talk a hit. It isn’t as overtly experimental as Extremely Loud, whichincludes series of photographs, blank pages, and multi-coloured handwriting, but it’s still a remorselessly unwieldy tome that takes us incredibly close to his characters’ thought processes: we delve inside their heads, sometimes to the point of claustrophobia. But in keeping with his previous work, which dealt with the Holocaust (Everything) and 9/11 (Extremely), it depicts the impact of a drastic event: the destruction of Israel, touched off by an earthquake. Jacob wonders whether he should leave his family and help his ancestral home.

So stuffed is Here I Am with digression, rumination, and recrimination, it’s no surprise Foer says he relishes book tours, so readers can help him interpret what he has written: “If someone says, ‘Why do you think Jacob did this thing in this situation?’ usually I want to say, ‘I don’t know. What do you think? Let’s talk about it.’ It’s not Socratic; it’s that I’m curious.” On a sunny Yonge Street patio in Toronto, Foer, trademark oval tortoise-shell specs in place, sips at a pint of Great Lakes’ Miami Weiss (“Miami nice,” he affirms), and tells Hazlitt about the tribulations of writers, the sympathy of readers, and letting your subconscious lead the way.

*

Mike Doherty: How did this book come to be?

Jonathan Safran Foer: It was a sloppy, inefficient process. It had a lot of starting points. I did write something for HBO which shared [with Here I Am] this inciting event of a discovered cell phone with sexual texts. At some other point—I don’t even remember if it was before or after—I had this mental itch about an earthquake in the Middle East, and I don’t know what inspired it. For years, I’d been working on a story that took the form of notes to actors. Stuff comes together.

I think there’s a subconscious structure inside of us that is yearning to be expressed, that is not only more interesting but more authentic than the kind of structure we might apply: “I’m going to write a book about this. It’s going to be divided into five chapters like this. There’ll be a rise and a fall, and this character’s going to be representative of this.” One can do that, but then you are ceding all control to yourself, as opposed to being open to fortuity and accidents, and weird rhymes and all the great things that happen if you just allow them to.

At a certain level, you took control and said, “I don’t want this to be a TV series. I want this to be a book.”

Well, the TV series was very different. It was more that I don’t want to devote the next five years to being a TV writer. It stops being writing and starts being show-running, which is managing personalities and being on-set and doing all kinds of things that weren’t how I want to spend my time. Amazing people dream of doing it and do it great; it’s just not my thing. Would it have been gratifying to see a TV show that I made? Yes. But a book is singularly special for me.

Your protagonist, Jacob, writes for TV, and he’s unfulfilled. He keeps working obsessively on a bible for another TV show that becomes his writing outlet …

I wanted him to write a TV series in large part to have that bible. That was the thing that interested me: that form, which predated my writing for TV. And my writing about divorce predated my divorce. It’s really odd, but the things that I was interested in, I was interested in for really purely aesthetic reasons.

You mention a “mental itch” about the earthquake, and the personal and the political come together here, as they often do in your work. When you write something for aesthetic reasons, how does the political come into it? Do you have to sit and think about, “This is exactly what would happen if there were an earthquake in Israel” and be very serious about working through these things?

That I was serious about, and I ended up getting help from some people in the Israeli military who have done military history in the U.S. for some journalists—I was pretty rigorous about getting that right, but also for aesthetic reasons. For me to have imagined that [entirely], it wouldn’t have been interesting, because I wouldn’t have known how to get to the stuff that was interesting.

In the book, a whole host of countries declare war on Israel. Do you sense that quite possibly that would actually happen if there were a major earthquake there?

I was trying to create something that would be useful in the book; I was not trying to write the most plausible scenario. It’s not plausible that Syrian rebel groups are going to all unite, or that Sunnis and Shia are going to unite, or Hamas and Hezbollah, but it’s not outlandish. It fuels the drama of the story.

You’ve been called a “European novelist writing in America,” but despite the events in Israel, the focus is on your characters in the U.S. Does this feel like a particularly American novel to you?

No, it feels like a novel very much about home and different notions of home. America is one kind of home, like an ancestral homeland is another kind. A house is kind of home; a familial unit is kind of home; a relationship is kind of home. I think America and the quality of being American is important to the book, but primarily as an example of a home.

Under one roof, you have a number of characters—including Jacob’s cousins from Israel, who have very different ways of looking at the world. Is home a place where we can bring together disparate ideas and make them either coalesce or achieve a productive tension? What’s the relationship between home and the outside world that people are bringing into it, for you?

That’s a really interesting question that I don’t have an easy answer to. I think there’s two versions of it. One is in the title, Here I Am, and I think that’s the one Jacob sort of subscribes to: wanting to have an ultimate home, an ultimate identity, that the paradox has become unsustainable. “I don’t want to be both in this marriage while also feeling like I want to be an individual in the world. I don’t want to be a parent who is seemingly devoted to parenting while also being a professional who is seemingly devoted to himself. I don’t want to have religious values and secular values that are in conflict. I want to be integrated.” And I think [Jacob’s eldest son] Sam is suggesting something a little more along the lines of what you were saying, like, a home where these paradoxes can be sustainable, where you can hold opposing ideas in your head and in your life at the same time.

Are the differences between them due to their generations?

Um, I don’t know if it’s generational or that Sam is a little more developed as a person. The book is ostensibly about Sam’s movement into adulthood, but it’s also about Jacob’s movement into manhood and his [own] bar mitzvah. In the end, I imagine most readers’ loyalties are with [Jacob’s wife] Julia and Sam. Loyalty might not be the right word, but if you had to locate where hope was in the book, the potential for happiness, it’s with them.

A number of authors, Jonathan Franzen among them, like to write characters who are ostensibly unsympathetic but win you over. What you’re describing seems like the opposite process …

Yeah, I think that might be right. I don’t know that one is ultimately alienated from him. Even if you are disappointed or frustrated by him, he’s a human, and he’s worthy of sympathy, if not loyalty. It’s an idea I’ve become interested in a lot in my own life—the balances between loyalty and, “I understand you but I can’t forgive you.” I think we feel loyalty to the family, so we’re rooting for Jacob and Julia together. That’s how I felt, anyway, and some readers I was talking to said the same thing.

It’s not a conventional novel, but considering how experimental/postmodern your other books were, were you consciously looking something that would be less overtly experimental?

No, it’s just where my aesthetics were, where my concerns were, and I wanted the form to suit the content. I wanted it to be a book that took place in living rooms and kitchens and bathrooms and had conversations and intimate relationships. It’s less brightly lit.

So in theory your next book could be something like the last one, with pictures and different coloured writing …

It could be. I may not write another book. I have no idea. There’s no place where I’m in a rush to get to.

You’ve said in the past that you define yourself as a novelist, so it’s interesting that you say you don’t know if there’ll be another book.

I assume there will. I don’t know if there will, but it took me a long time to make this one.

Was it more difficult in some ways to write this book?

I think writing itself was probably more difficult, but that’s largely just because life was more full. More things were requiring my attention and time. This book took me the same amount of time as my other books did. It just took me a lot more time to get to the beginning of it, to find a project that I really cared about. Writing the book only took two or three years.

The galley copies include acknowledgements, in which you write, “thank you, Michelle [actress Williams, whom Foer is dating], for making me an office where I could finally write and a home where I could finally stop writing.” Had the writing process become difficult for you?

Yeah, I suppose it had. When I would go to the office, wherever it was [Foer has been known for writing in libraries and cafés], it was hard to find something that I cared about enough, and it was hard when I was not writing not to think about that fact. And then I was able to find a balance.

Was it hard to switch off?

Yeah, it was. I’m happy when I’m inside of a book, and I’m not when I’m not inside of a book. It’s such a big part of my identity, and I find it very fulfilling, gratifying, and fun also, expressive, and it’s a language for things that have no other language. When I’m in it, I feel good, and when I’m out of it, I feel bad.

If I were a short story writer, I wouldn’t feel it as extremely, because, “OK, I can work on another short story!” With the novel, there’s only one project that takes up a long period of time. You’re putting a lot of eggs into one basket. It can be the source of a lot of happiness and a lot of worry.

Does that always resolve itself to your satisfaction?

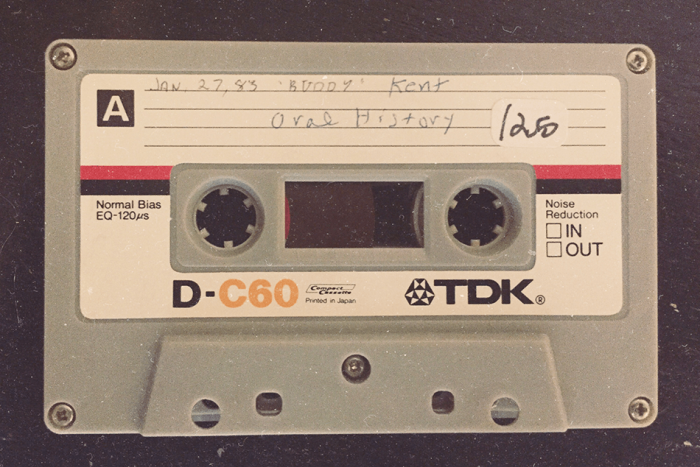

No, I write lots of things that I throw out. The other day, I opened a box and found a draft of a novel that I was working on in between my last one and this one—300 pages, something like that; it didn’t work out. I just didn’t care about it enough. I don’t look at that as a profound waste of time, but it’s very disappointing.

I don’t find it terribly difficult, because I’ve had enough experience with writing to know that those ideas might resurface in other ways, and it’s obviously a necessary part of the process. I know that about myself.

You can happily throw out—

Not happily, but I am not swinging from the rafters.