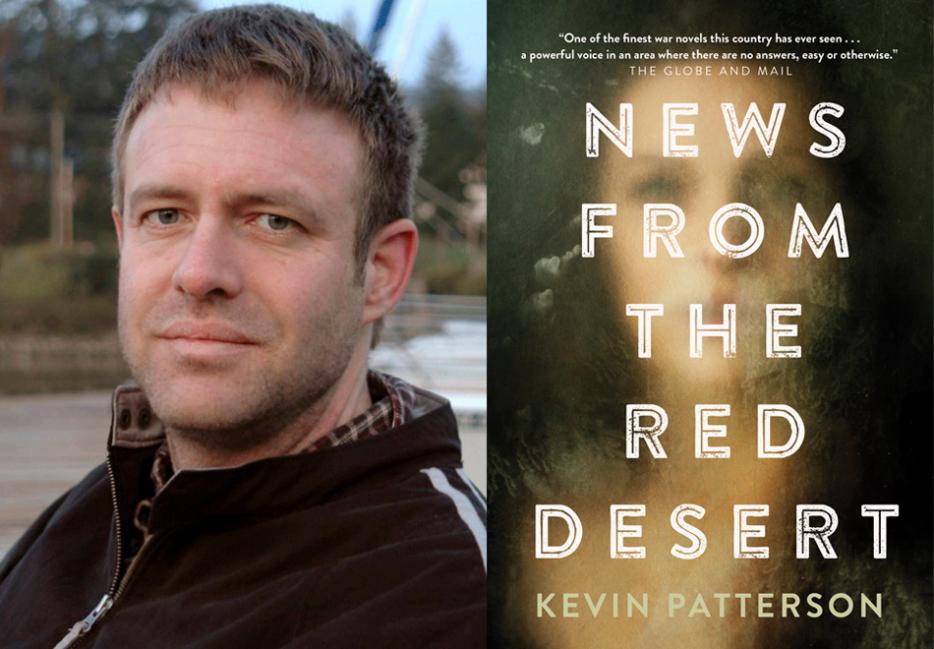

Kevin Patterson was eager at first to run the ICU at the allied air base in Kandahar: Having spent long years as an underused medical officer in the dust bowl of Shilo, Manitoba, he was more than ready for action. But he found himself in what he calls an “arid and oppressive” area, in the midst of an enterprise he came to doubt. His novel News from the Red Desert (Random House Canada) draws on his six-week stint in 2007, at a time when, he says, “clear-sighted people saw that there was no happy ending.”

The book is more than just a screed: Patterson is one of those rare authors who can make the dictum “Write what you know” seem more of a liberating offer than a set of shackles. Patterson’s first book, The Water in Between (Random House Canada), is a memoir of sailing, as a novice, from Vancouver Island to Tahiti and back. His debut novel, Consumption (Random House Canada), was inspired by his occasional work as a doctor in the Arctic. And News from the Red Desert portrays the intensity of the Afghanistan War in unflinching detail refracted through the varied perceptions of conflicted characters. The Pakistani workers at the (real-life) Green Beans café either embrace or distrust Western culture; an American sergeant leaks photos of army atrocities; two U.S. generals find themselves at loggerheads about tactics as both look to charm the media; and Deirdre O’Malley, an American journalist embedded with Canadian and American infantry, is on side with the troops.

One of the generals tells Deirdre, “In the real world, chaos lies at the heart of violence.” Patterson himself agrees. He believes novelists—not filmmakers or journalists—are the people who can accurately represent the hardship and existential uncertainty provoked by a war zone. His novel is the first to emerge by a Canadian who served in Kandahar; Patterson hopes there will be more.

Mike Doherty: Often in your books there are people who seem energized by the presence of real peril. Considering you keep going back to the Arctic, does that factor figure into your own travels?

Kevin Patterson: It does. We all crave trouble. My last novel, Consumption, was all about the diseases of affluence: diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity. Also on a psychic level, when you live in a safe place, a mental posture starts to be produced—one of slouching, of ennui. Young people want to be heroes. They want to tackle hard problems and acquit themselves well, and the suffocating safety of our lives here sits uneasily on lots of people’s shoulders.

When you have a war, almost everybody has enormous enthusiasm in the beginning. When you think about the World Wars, the streets of London, Paris, New York, and Berlin were filled with throngs of people craving [war], and when Canada went into Afghanistan, there was a similar sort of delight, not least among journalists. They went from being courthouse reporters to war correspondents in body armour and helmets. They were so enthusiastic, which is really uncomfortable, ‘cause it’s their job to question the powers. When there’s a highly emotional public enthusiasm, that’s exactly the time when the media needs to stand up and say, “Let’s think hard about this.”

They completely failed us, for obvious reasons. Journalists love these brave, wise-cracking young men and women that were out in the field making the best of a really challenging situation, and the soldiers and the journalists felt far more alive there than ever before or subsequently.

Was that true for you?

For doctors, it’s a little more complex, because emergency rooms have an intensity about them. People are coming in from accidents, and it’s necessary to make good decisions really rapidly. But there’s something more revved up about a war zone. There are rockets falling in the camp from time to time, and the human membrane is wired for violence. In its absence, it idealizes it and represents it as purifying and beautiful. That’s why Breaking Bad had to be so violent. That’s why Game of Thrones draws 30 million eyes every Sunday night. In actuality, [violence] is horrific and ugly; it’s about little children being eviscerated, and it’s random and chaotic. It’s not about the bad guy getting his comeuppance; it’s about perfectly innocent people who have nothing to do with the agendas of the people making decisions, being shattered.

What separates a doctor’s experience of the randomness and messiness of violence from a soldier’s?

Doctors might be a little bit less enamoured of violence because we’re more familiar with it. We understand that it’s mostly men beating up women, and big guys beating up little guys. It’s ugly, and it’s horrific. The war version of that is big guys shooting little, poor people.

For a mostly peaceful country like Canada, its soldiers will be electrified by war. You have to spend twenty or twenty-five years where [for] all but six months of that, maybe, you’re at peace. That’s hard on the psyche.

The doctors have [had] a life of taking care of shattered people; over there, they take care of shattered people. So it takes much less discipline and courage to remain engaged with what you do.

For those on military bases in the middle of a war, is there still a feeling of waiting around, of lack of direction and meaninglessness?

Yeah, that’s at the heart of war. Our narratives try and downplay that. We talk about smart weapons and surgical strikes, and the Kathryn Bigelow movies [are] about the incredible precision, power, direction, and intelligence of the military operation, but fundamentally, it’s a bunch of people who don’t know anything much about their opponents, using tools that they understand to be mostly ineffective and maybe counterproductive.

As a nation, we went [to Afghanistan]; we spent 25 billion dollars and killed thousands of people and lost 160 of our own, and another 1000 [were] grievously wounded, all for a pursuit that we were barely able to articulate at the time. There’s a consensus that we failed, and that’s the lesson of war. It’s the shedding of systematized thought, of the usual priorities that make our lives meaningful.

And then there’s the question of where Canada fits into all this. In your book, there are Canadian soldiers who get blown up, but they’re a relatively small piece of a larger puzzle.

Yeah, Canadian reportage talked about Kandahar as being mostly a Canadian show, but that would have been news to the 80 per cent of people there who are Americans. Some humility would be appropriate, in that the Afghans never distinguished between Canadians and Americans. We were all the ferenghee.

Canada has been changed by our experience in Afghanistan. What was edifying about what we did there, I think, is [learning] the limits of violence—the limited application. Violence is not completely useless. It would be much easier if it had no role and was never necessary, but we should have acted in Rwanda. If we had sent an infantry division, or even a brigade, it would have made a huge difference. A million people were killed in ninety days because nobody did anything. But most situations are probably made worse by violence; where you go in and occupy another country very quickly, you’re resented more than the problem that you arrived to solve, and maybe we learned about that. I don’t think that the military would be able to sell a mission like Afghanistan to the Canadian public today without more skepticism and analysis. We understand that despite the best of intentions, and the ferocious dedication, commitment, loyalty, and devotion of the people that went there, we didn’t make things much better.

In the Acknowledgments, you mention, “If war bore more relation to its fantasized version, war novels would be both less necessary and easier to write.” Why did you feel that it was necessary for you to write News from the Red Desert?

I think books like [Erich Maria Remarque’s] All Quiet on the Western Front, [Sebastian Faulks’] Birdsong, and [Pat Barker’s] Regeneration trilogy almost validate the idea of a novel: Those novels have stood up against the hyperbolic movies and the non-fiction journalism perpetrated by the war enthusiasts. The novelist can go into the heads of her characters. She can get at a central truth, whereas the CBS television producer can only ever get at the briefest glimpses of the superficialities, and if it’s her blond hair sweeping into the wind as she shouts into the microphone as AK-47 bullets are flying over the wall, all the better. But the novelist goes into the heads of the suffering people. That’s what war is about, of course—suffering.

Does it take a particular kind of perception or experience or even person to translate the chaos of war into fiction?

World War I and World War II produced lots of great novelists, partly because of the draft. Because once you have conscription, you’re taking people who wouldn’t volunteer to be there, and you’re making them endure it. So Norman Mailer and Joseph Heller and that whole class of bookish, thoughtful, skeptical people, are put in the war, and then they come back with reports. But when you don’t have the draft, you are selecting for people who believe in the cause, who are going to be less questioning. And when they do write about it, they write American Sniper.

There are passages in your novel where one person has a thought, and then it leaps into someone else’s head, and then another ...

Do you know what murmurations are, when 30,000 swallows all fly around in a ball? They seem to move together faster than any kind of communication could account for. This is how we acted after 9/11. These waves of sentiment went through a whole country, and then we had people like Michael Ignatieff and Allan Dershowitz—admirable liberals, who are all about dignity and justice—defending torture. And tons of us took extreme positions. I thought that Afghanistan could be helped by military force, initially. It’s a preposterous idea in retrospect. … And the whole [of Canada] thought that; there was no opposition to that war of any scale. I was just trying to represent the way sentiment just floats through people—there’s something about that phenomenon that makes all of this possible.

In the book, these thoughts jump from around between ostensibly very different people: Are you offering the possibility of empathy across cultures?

That’s the essence of the book. If this were just a “war is bad” book, it would be like a lot of others, and it would be true but dull. It’s about this idea of empathy, and “Why does PTSD exist?” People come back having suffered those moral injuries, where they’ve done things that they know are terrible, and that’s because of the empathic response. It would be a vastly worse world if you could send those people over there and make them do those things, and have them come back just fine. Fundamentally that is where our hope lies: to be able to look upon that havoc and understand what it feels like to be on the receiving end. And torture exists because of a failure of empathy.

Your essay about your time in Kandahar in the anthology Outside the Wire mentions just how far from home everyone was, and in News from the Red Desert, all of the characters are far from home—even the people who work at Green Beans. There are no actual Afghan characters; the Afghans are at one remove from the narrative.

I never got outside of KAF. I was on the base the whole time there, mostly in the hospital. When Afghan combatants in uniform were blown up, they were brought in. It was often impossible to talk to them because they were so sick. To the extent that I had any conversation with the Afghans, it would be the dads of the kids who were brought in—the mothers weren’t allowed to travel.

And [the dads] were a tough read. A) We were taking care of their kid that they loved, and they wanted that kid to get better. B) They were furious because their kid had been hurt by a war that was brought to them by people who looked like me. C) It was often someone who actually shot the kid who looked just like me, or [the kid] picked up a landmine that was left behind by someone like me, or some unexploded ordnance. I thought that I could discern layers of appreciation and hostility in that interaction, but because they so rarely spoke English, it was not possible to have a heart-to-heart conversation with any of them. So there’s just not a lot of Afghans in this book, it’s true, but we make war possible by excluding the Afghans from our conversation. It’s all about us.